Tumefactive demyelinating lesions (TDLs) are rare demyelinating lesions that present acutely as aggressive tumor-like central nervous system (CNS) lesions. While 70% of patients with TDL progress to develop multiple sclerosis, the presence of a TDL may also be considered an independent syndrome (

1). Diagnosis of TDLs is challenging because these lesions may present with vague, atypical symptoms (

1) and appear radiologically indistinguishable from other CNS lesions on MRI (

2). Patients with TDLs, similar to those with other rare neurological disorders, may present in a psychiatric setting, where these conditions pose significant diagnostic challenges.

Classically, patients with demyelinating disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, have motor, sensory, cognitive, or cerebellar symptoms or focal neurological symptoms, such as unilateral vision loss. However, the clinical presentation of patients with TDLs may differ from those with other demyelinating disorders because the mass effect of the growing lesion pressing on surrounding tissues results in diffuse neurological symptoms. These vague symptoms associated with TDL, such as changes in affect or cognitive impairment, may initially be attributed to psychiatric illness (

1,

3).

Here, we describe the case of a female patient with new-onset depression and psychosis who was eventually diagnosed with TDL.

Case Presentation

A 26-year-old female patient was brought to the emergency department by a family member concerned about her mental status. At bedside, the family member indicated that the patient had been responding to questions inappropriately, had ceased to care for herself or her children, and had not attended work the previous week. The family member also reported a remote psychiatric history of major depressive disorder, suicidal ideation, and cannabis use. However, the patient was in recovery and had not required or received psychiatric treatment for several years. There was no family history of mental illness.

The history obtained from the patient was limited because she was inattentive, with poverty of speech. She appeared to be confused and had a flat affect as well as apathy, psychomotor retardation, and impaired cognition. She was oriented to place and person only. She responded to questions with simple but distressing statements, such as “I have no clue” or “I need help” and “I’m not all there.” A review of systems was positive only for headache. She reported using cannabis a week earlier and had a cannabinoid-positive urine drug screen at the time of admission. Results from other initial laboratory tests, including a complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel, were within normal limits. The patient was admitted to a psychiatric hospital after scoring high on a suicide risk screening tool and answering “probably” when asked whether she had suicidal thoughts.

Upon admission to the psychiatric hospital, she continued to remain oriented only to person and place. She was diagnosed with major depressive disorder with psychotic features and started on olanzapine (10 mg nightly) and sertraline (50 mg daily). She remained in her room and did not participate in group therapy. The treatment team noted that she showed no improvement. On the eighth day of admission, she began to experience nausea and emesis. Noncontrast head computed tomography (CT) revealed vasogenic edema within the left frontal lobe, left parietal lobe, and bilateral temporal lobes and a mass effect on the left lateral ventricle with midline shift. The patient was emergently transferred to a medical floor.

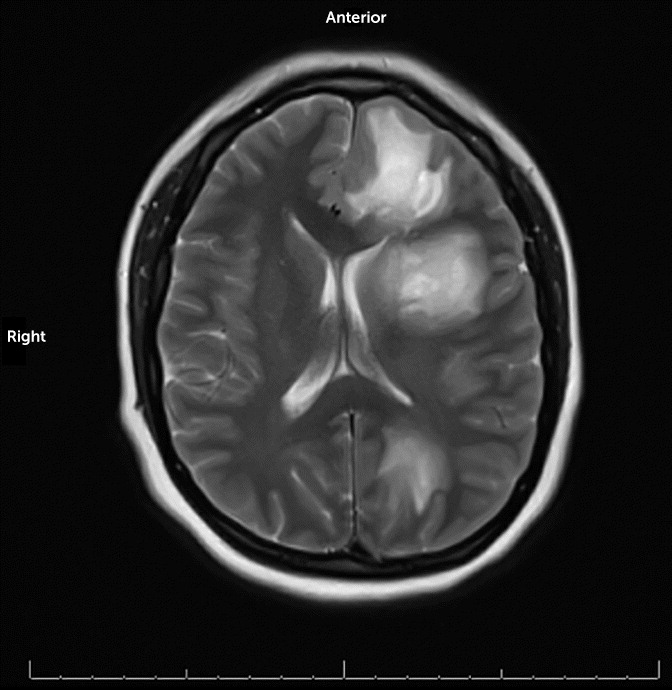

Repeat complete blood count revealed leukocytosis with a neutrophilic predominance and elevated inflammatory markers (

Table 1). Upon admission to the medical floor, the patient was afebrile with no cranial nerve or other focal deficits. MRI revealed T2 hyperintense lesions, which were most pronounced in the left frontal and left parietal lobes, in addition to scattered necrotic-appearing, peripheral lesions (

Figure 1). Differential diagnosis included potential primary or secondary CNS malignancy, such as lymphoma. Courses of dexamethasone for edema and inflammation and levetiracetam for seizure prophylaxis were initiated. She was also administered empiric broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics because of the concern of a possible infectious etiology. In addition, she underwent a transthoracic echocardiogram with unremarkable findings. Blood cultures obtained were negative.

On the 11th day of admission (third day on the medical floor), the patient experienced new-onset moderate weakness of the right upper and lower extremities; however, no acute stroke was identified. She also began to experience apparent global aphasia and episodes of inconsolable screaming and weeping. The psychiatry consultation service recommended against the use of dopamine antagonists for these episodes because of a concern for a lowered seizure threshold and suggested switching from levetiracetam because of the associated risk of adverse neuropsychiatric symptoms. Olanzapine was discontinued, and lorazepam (2 mg intravenously every 6 hours as needed) was started. Levetiracetam was discontinued, and oxcarbazepine (300 mg twice daily) was started and titrated up to 450 mg twice daily. Sertraline (50 mg daily) was continued.

A brain biopsy was obtained. The intraoperative pathology report revealed reactive astrocytes with macrophages, suggestive of an active demyelinating lesion, with no tumor present. The patient was started on a 5-day course of intravenous methylprednisolone. Antibiotics were discontinued. The patient’s extremity weakness and aphasia gradually improved following completion of the steroid course: she was better able to follow commands and communicate verbally and demonstrated improved strength on her right side. She was discharged to her home.

Two months later at her outpatient follow-up visit, the patient reported a complete resolution of right-sided weakness. She continued to exhibit expressive aphasia and acalculia. Her mood was described as euthymic, and her affect was mildly constricted but appropriate. There was no evidence of any psychotic symptoms. Sertraline had been increased to 100 mg daily by an outpatient primary care physician; the patient had also completed a 30-day course of oxcarbazepine, and the prescription was not continued. She remained living with her family and required assistance with activities of daily living.

Discussion

TDLs were first described in 1993 by John Kepes as large, focal cerebral demyelinating lesions (

4). The most common presenting symptoms among patients with TDLs include aphasia, confusional state, and memory dysfunction (

5), all of which were reported for the patient described here. Patients with TDLs and other demyelinating disorders may present in a psychiatric setting with behavioral abnormalities and cognitive symptoms. They may also present with psychiatric symptoms in a medical setting and benefit from the involvement of a consultation-liaison psychiatry team. For our patient, symptoms of worsening headache and emesis guided the treating psychiatrist toward the decision to obtain a noncontrast head CT scan. Other tests with clinical utility may include a brain MRI and EEG. A lumbar puncture may also be helpful to identify oligoclonal bands or other markers within the cerebrospinal fluid, although a lumbar puncture was contraindicated for our patient because of the mass effect identified on neuroimaging and a concern for herniation.

Demyelinating lesions are not specific to TDL or multiple sclerosis and appear in other conditions, such as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Certain patients with particular risk factors (e.g., immunocompromised patients) may develop progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy secondary to John Cunningham virus (

6). Many treatments for cancers, organ transplantation, and chronic inflammatory disease cause immunosuppression (

6). For patients with new demyelinating lesions, clinicians should consider screening tests to rule out infectious causes of immunosuppression, such as HIV and hepatitis B and C (

7). Demyelinating lesions may also occur with viral infections (e.g., HIV), autoimmune disease (e.g., Behcet’s disease and neuromyelitis optica), and drug-induced complications (e.g., tacrolimus) and as paraneoplastic manifestations of remote malignancies (e.g., renal cell carcinoma) (

1).

The demyelinating lesions observed in patients with TDL may be difficult to differentiate from primary CNS tumors, such as gliomas, neuroectodermal or ependymal tumors, craniopharyngiomas, germinal tumors, meningiomas, and neurinomas (

2,

8). Biopsy may be warranted, even for a patient with a preexisting diagnosis of multiple sclerosis, because patients with concurrent multiple sclerosis and primary CNS tumors have been described in the literature (

9,

10). CNS vasculitis is another well-known clinical and radiological mimic of demyelinating lesions (

11). The most common syndromes associated with CNS vasculitis include antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis, Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, scleroderma, and systemic lupus erythematosus (

11).

Finally, although data specifically for TDLs are limited, psychiatric symptoms are common among patients with demyelinating illnesses such as multiple sclerosis (

12,

13). The particular symptoms differ because of variations in the size and location of the lesions. For example, frontotemporal involvement can result in abnormal affect and behavioral changes. However, symptomatology associated with demyelinating illness, similar to that observed with other neoplasms and solid brain tumors, is of limited localizing value (

14). Among patients with multiple sclerosis, anxiety and depression are the most commonly reported psychiatric disorders, with 57% (

15) and 40% (

16) of patients reporting clinically significant anxiety and depression, respectively. Anxiety and depression result in lower quality of life, increased level of disability (

15), poor adherence to treatment (

17), and increased number of hospital admissions and relapses (

18). Additionally, rates of suicidal ideation are estimated to be 2 to 14 times higher among patients with multiple sclerosis than among individuals in the general population (

19); therefore, identification and treatment of psychiatric conditions for those in this patient population is essential.

This case report illustrates the necessity for a broad differential whenever a physician is assessing new-onset neuropsychiatric conditions.