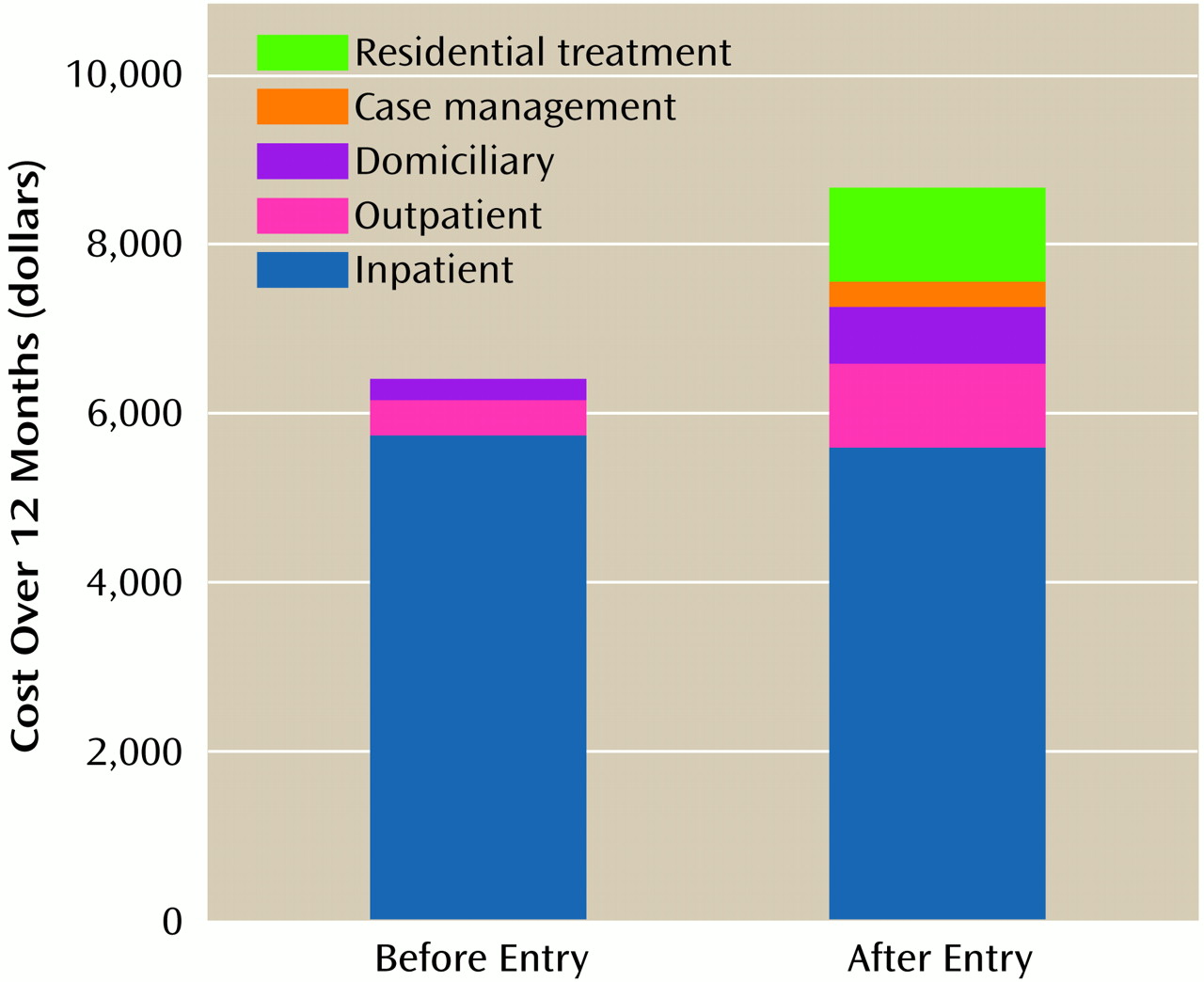

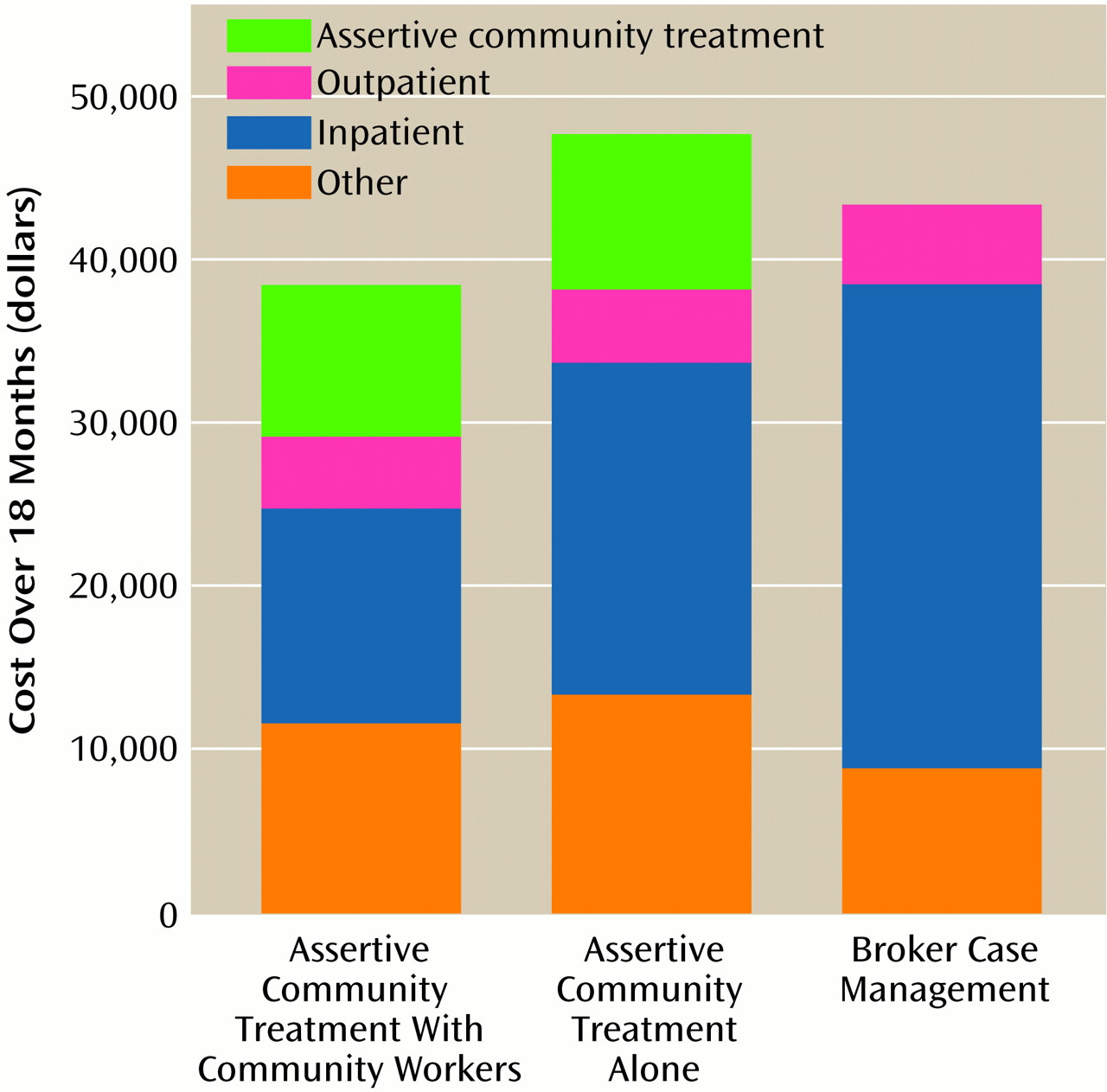

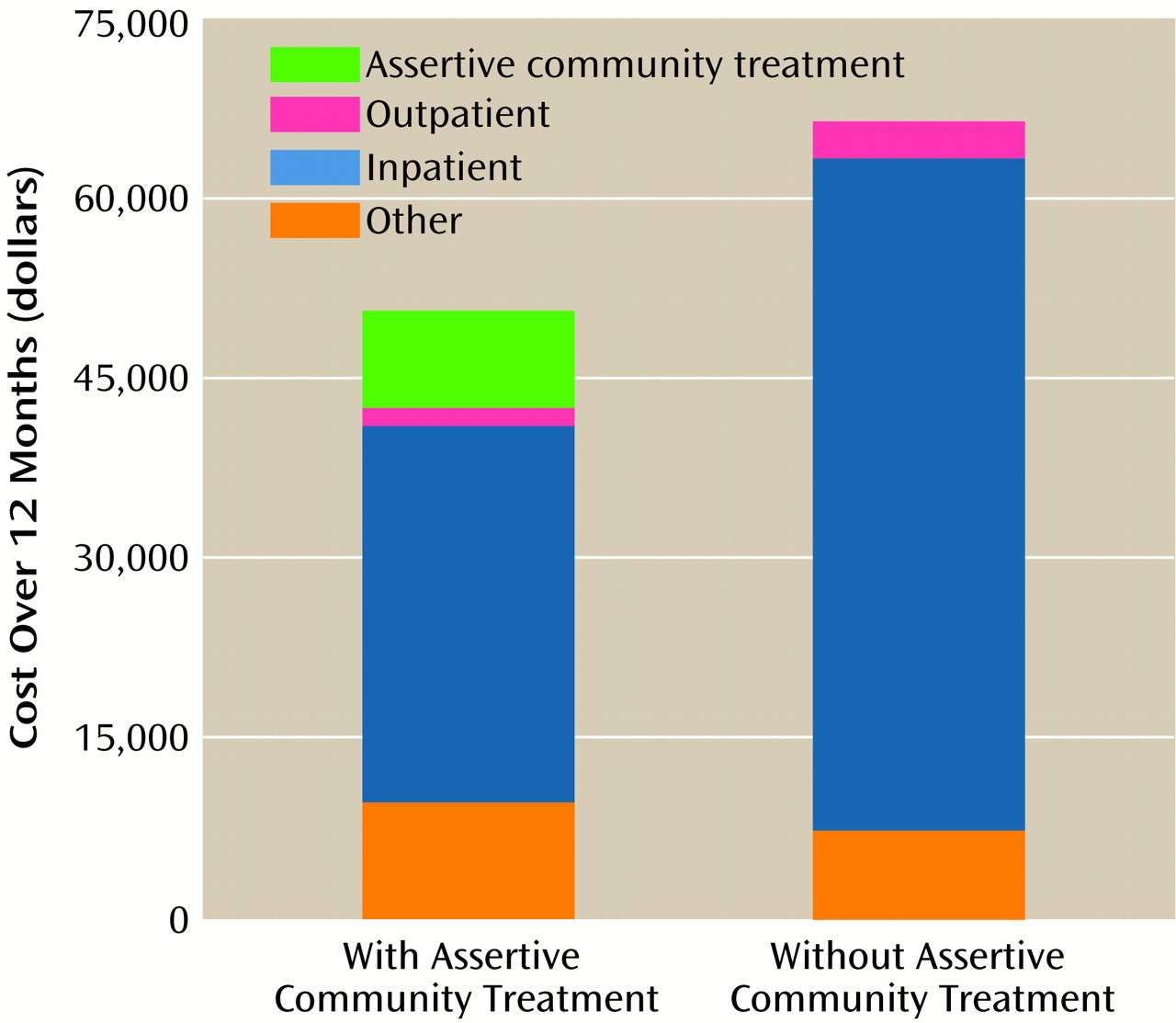

This review of a diverse array of innovative programs suggests that although enhancing services for homeless people with mental illness generates significant benefits, costs may also increase, especially when outreach teams are used to contact the most vulnerable segments of the homeless population. This increase in service use and cost is not surprising, since these programs are designed to serve severely ill people with virtually no resources and poor access to services. The two studies that found that increased program costs may be offset by reduced inpatient costs focused on unusually heavy hospital users and thus apply to only a small segment of the target population. We thus observe that although they are generally effective, these programs can be cost-neutral or more expensive depending on the specifics of program design and target population.

As we consider the transition from these research results to policy and practice, two additional questions emerge: 1) what is the relationship of human service delivery and material support in the design of programs for homeless people with mental illness?; and 2) should society be willing to pay for services that are both more effective and more expensive?

Material Subsidies: Program Effectiveness Versus Jumping the Queue

Each of the programs reviewed above included a subsidized housing component as a central feature of the experimental treatment. Several programs also reported increased public support payments among their clients

(8,

18), and one showed that increased public support was associated with superior housing outcomes

(18). Since each of these programs had negotiated special access to housing resources, and one operated a joint outreach program with the Social Security Administration

(14), they did not actually increase the available pool of resources. Rather, they helped their clients jump to the head of the line, displacing others who were probably just as deserving

(25). To the extent that the effectiveness of augmented service programs is attributable to this queue-jumping function, dissemination of these programs will require increasing the availability of these resources. It is not surprising that effective service programs for homeless people include housing and income supports, but it is only when one moves from research to broader practice that the challenge of increasing the pool of such resources emerges as a major challenge and potential barrier to widespread dissemination.

Although some policy analysts have concluded that increasing housing and income supports should be the principal policy initiative for homeless people with mental illness

(15,

26), the relative importance and likely interdependence of clinical services and material supports for this population is understudied and is an important area for future research.

Societal Willingness to Pay

Our review of research suggests that innovative programs for homeless people with mental illness are modestly more effective than standard care, but they may also be more expensive. Furthermore, we have suggested that in the transition from research to practice, these programs must incur additional costs to increase the available pool of housing subsidies and income supports. What, finally, are the implications of these cost-effectiveness data? What can we recommend to policy makers and program planners?

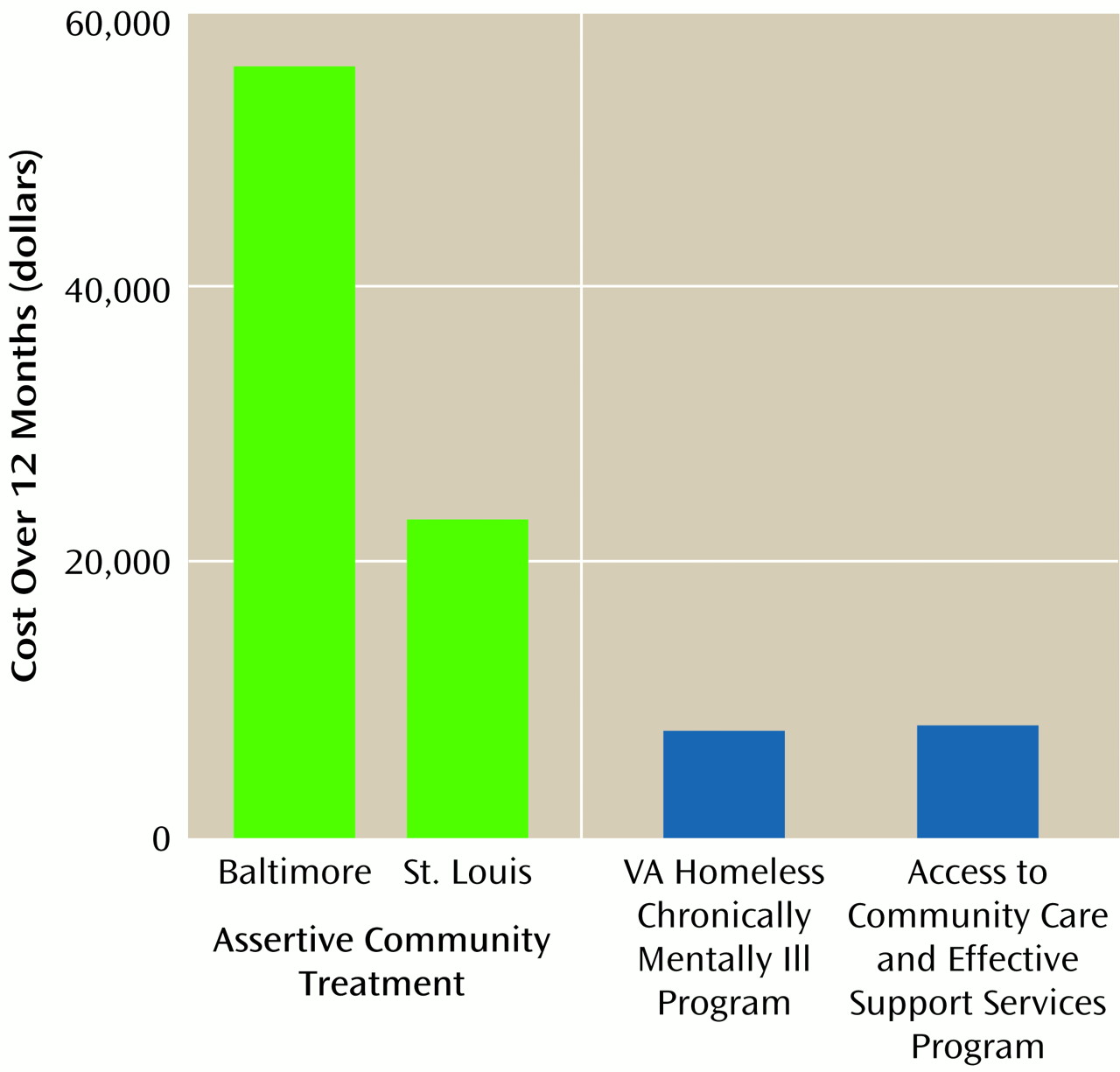

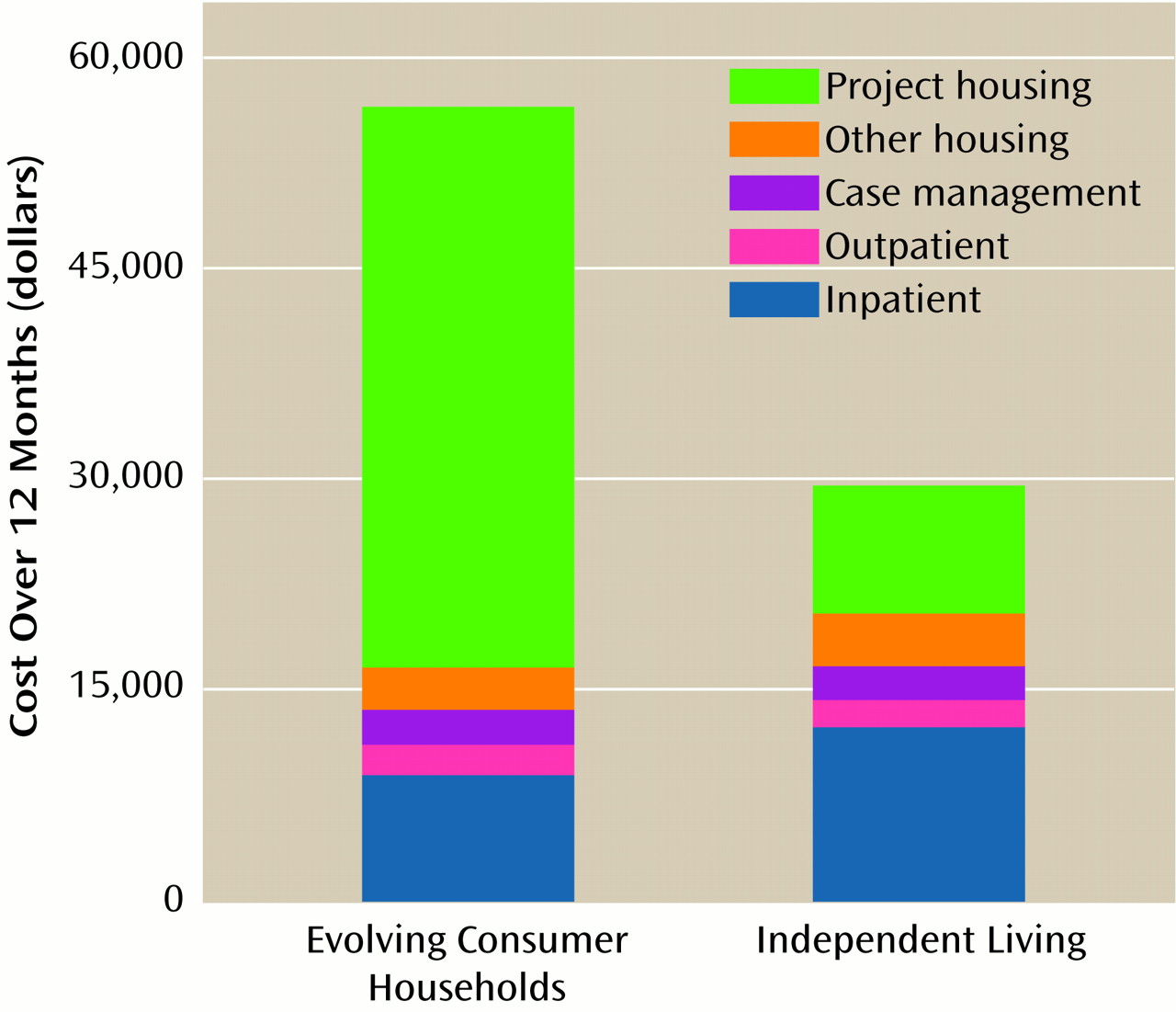

If we had found that these new treatment approaches were both more effective and less costly than conventional alternatives, our recommendation to implement them would have been straightforward and based entirely on research data. Our counsel would have been positive and definite: “If you invest in these programs, your clients will have better outcomes, and by redeploying funds from old models to new, you will save money with which you can treat additional clients.” This statement does appear to be justified in the case of assertive community treatment for the most resource-intensive 10% of clients.

Since most of the programs we have reviewed are likely to be both more effective and more costly for the typical client, the decision of whether they should be implemented depends on whether the value of these benefits equals their additional cost. In this situation, cost-effectiveness analysis, in which we compare the costs of unmonetized outcomes (e.g., dollars per day of reduced homelessness), is an incomplete guide to decision making. Rather, cost-benefit analysis is needed, in which the dollar value of health gains is estimated

(16,

27) to determine whether they exceed costs.

Since it is the public that pays for these health benefits, the standard for determining their value is the public’s willingness to pay for them. Economists have developed two methods for empirically estimating societal willingness to pay for various public goods. The first method, revealed-preferences assessment

(28,

29), attempts to extrapolate from goods and services that society pays for to those that are in question. For example, by using data on wage premiums for hazardous (i.e., life-endangering) employment, the value of a year of healthy life has been estimated at $20,000–$350,000

(27). If, using standard procedures, we could convert health improvements for homeless people to a measure equivalent to years of healthy life gained (quality-adjusted life years)

(16,

27), we would be able to assign a monetary value to these health improvements.

In the second method, contingent valuation

(28), representative samples of the general public are directly asked how much they would be willing to pay to achieve various personal or societal objectives, such as improving the situation of homeless people with mental illness. One study, for example, found that people were willing to pay $301 in 1999 inflation-adjusted dollars to avoid a day of incapacitating drowsiness

(29). If we roughly equate the dysphoria of such a state with a day of homelessness, we could estimate that the reduction of 60 days of homelessness by critical time intervention would be worth $18,000, easily enough to pay for the program.

Although neither of these methods has been directly applied to the evaluation of programs for homeless people with mental illness, economic analysis of these programs would be substantially strengthened by careful research along these lines.

One final question remains to be addressed. What if it is determined that the benefits of the specific programs evaluated here are not worth their additional cost? Does this mean that programs for homeless people with mental illness are, in general, not cost-effective? Should the programs that are currently in operation be closed down? Are they a waste of taxpayers’ money? The simple answer to these questions is “no.” Research studies like those reviewed here focus on new technologies that may improve standard services, not to the standard services themselves. A decision that an augmented program should not be widely implemented because it does not generate enough benefit to justify its cost says nothing about the comparison of standard programs with the alternative of providing no services at all. That question could only be addressed by a study that compares current standard care with no care, a comparison that would be as unethical to conduct from the research point of view as it would be unacceptable as a deliberate policy in a compassionate society.