Cocaine withdrawal is controversial

(1,

2), but increasingly it is recognized that cocaine withdrawal symptoms are predictive of a more difficult clinical course

(3). Although cocaine withdrawal does not result in the peripheral signs and symptoms of autonomic instability often seen in other drug withdrawal syndromes, cocaine withdrawal is associated with significant psychiatric symptoms

(4). The severity of cocaine withdrawal symptoms is predictive of treatment dropout and failure to attain abstinence in cocaine-dependent patients participating in outpatient treatment

(5,

6).

Cocaine withdrawal may be associated with changes in the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system

(7). As an indirect dopamine agonist, amantadine may be able to stimulate the release of dopamine and potentially ameliorate distress associated with cocaine withdrawal symptoms

(8).

Previous trials of amantadine have yielded mixed results. Two double-blind trials showed amantadine to be efficacious

(9,

10). However, several other double-blind trials did not show amantadine to be superior to placebo

(11–

13). These divergent results suggest that amantadine responsiveness may be limited to specific subgroups of cocaine-dependent patients. The beneficial effects of amantadine are likely to be greater in patients with more severe cocaine withdrawal distress. The study reported here reevaluated previously reported negative findings on the efficacy of amantadine

(13), specifically examining the efficacy of amantadine among patients with more severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms.

Method

Subjects included 61 men and women who met DSM-III-R criteria for cocaine dependence and who had been admitted to an intensive outpatient treatment program for cocaine dependence. Subjects gave written informed consent after being apprised of the study risks. Subjects were randomly assigned to receive 100 mg t.i.d. of amantadine (N=30) or identical placebo (N=31) for 4 weeks. A complete description of the study group and methods is available elsewhere

(13).

The severity of cocaine withdrawal symptoms at baseline was measured with the Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment

(14) at the first study visit. The Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment is an 18-item instrument that measures signs and symptoms associated with recent abstinence from cocaine. A general linear model was used to evaluate the interaction of medication group and baseline scores on the Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment. Independent variables included medication group, baseline Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment score, and the interaction of baseline Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment score and medication group. Dependent variables included the number of urine samples submitted containing less than 300 ng/ml of benzoylecgonine (benzoylecgonine-negative samples), the overall mean urinary benzoylecgonine level (log transformed), and the number of days of self-reported cocaine use during the trial. Pair-wise comparisons with the least significant difference test were used to compare the means of the three dependent variables in amantadine-and placebo-treated subjects with baseline Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment scores at or above the 67th percentile (more severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms) and below the 67th percentile (less severe symptoms). The 67th percentile was selected as the cutoff on the basis of data from two previous trials suggesting that initial Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment scores above the 67th percentile predicted poor outcome

(5,

6).

Results

Baseline demographic and drug use variables of the amantadine- and placebo-treated subjects did not vary significantly. About 80% of the subjects were men, and about 70% smoked crack cocaine. There was no difference between amantadine- and placebo-treated subjects in the number of psychosocial therapy sessions attended, nor was there a difference in psychosocial therapy attendance between subjects with more severe and less severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms. Support networks for the two groups were equivalent.

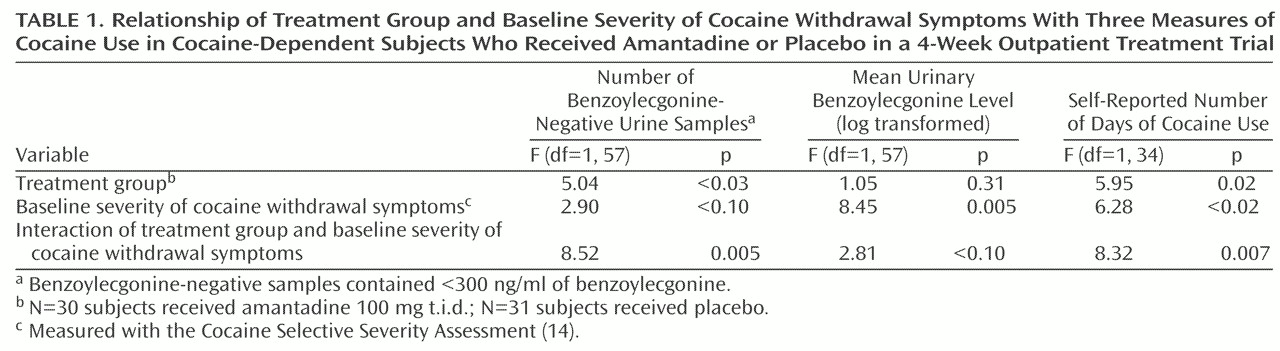

Among subjects with more severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms, amantadine was more effective than placebo in reducing cocaine use, as measured by either the number of benzoylecgonine-negative urine toxicology screens or the number of days of self-reported cocaine use. Log-transformed urinary benzoylecgonine levels also tended to be lower among amantadine-treated subjects with more severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms (

Table 1).

The beneficial effects of amantadine were also demonstrated in the subgroup of subjects with more severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms. Among subjects with high scores on the Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment, amantadine-treated subjects (N=9) submitted significantly more benzoylecgonine-negative urine samples than did placebo-treated subjects (N=11), a mean of 5.33 benzoylecgonine-negative urine samples (SD=3.54) compared with 0.45 (SD=0.93) for the placebo group (pair-wise comparison by the least significant difference test: mean difference=4.88, df=57, p=0.002). Amantadine-treated subjects with high scores on the Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment also had a significantly lower log-transformed mean urinary benzoylecgonine level. The mean level for the amantadine group was 6.20 (SD=3.00), compared to 9.11 (SD=2.39) for the placebo group (pair-wise comparison by the least significant difference test: mean difference=–2.90, df=57, p<0.03). The mean number of days of self-reported cocaine use among subjects with higher scores on the Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment who were treated with amantadine was 3.86 (SD=3.53), compared to 9.40 (SD=11.61) for placebo-treated subjects, a nonsignificant difference (pair-wise comparison by the least significant difference test: mean difference=–5.54, df=34, p=0.16). On the other hand, among subjects with lower scores on the Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment, there were no significant differences between amantadine- and placebo-treated subjects on any of the three measures of cocaine use.

Discussion

Among subjects with more severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms at baseline, amantadine improved abstinence. However, amantadine did not appear to be efficacious in subjects with less severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms. That amantadine was more efficacious in subjects with more severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms is consistent with the hypothesis that amantadine ameliorates cocaine withdrawal symptoms and may explain the varied results obtained in prior trials of amantadine. It is possible that the beneficial effects of amantadine in subjects with significant cocaine withdrawal symptoms could have been missed in some studies because of the inclusion of a significant number of other subjects with less severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms.

The efficacy of amantadine in subjects with more severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms may be especially relevant for clinicians struggling to effectively manage these hard-to-treat patients. In previous trials it has been demonstrated that cocaine-dependent subjects who are seen for treatment with more severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms are more difficult to treat

(5,

6).

The beneficial effects of amantadine over placebo were limited to a small subgroup (N=20) and therefore may have resulted from chance alone. This trial should be replicated in a larger study group in which subjects with severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms are prospectively identified. Nevertheless, these data suggest that amantadine may be an effective treatment for cocaine-dependent patients who have more severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms.