Although schizophrenia and depression have historically been considered to be separate diagnostic disorders, the observation has repeatedly been made that, from a symptom perspective, depression-like phenomenology occurs quite frequently in schizophrenia

(1–

4). In the early decades of psychopharmacology, however, it seemed most important to differentiate schizophrenia and depression in order to define most clearly which patients should be treated with antipsychotic agents and which with antidepressants. Nevertheless, the occurrence of the phenomenology of depression in a substantial percentage of patients with schizophrenia (as well as psychosis in patients with depression) has kept alive the twin issues of the appropriate descriptive boundaries between the two disorders and the best approaches to treatment. Indeed, these issues assume added importance, since it has been found that the occurrence of depression in schizophrenia has often been associated with worse outcome

(5), impaired functioning, personal suffering

(6), higher rates of relapse or rehospitalization

(7–

10), and even suicide

(8,

11,

12)—a tragic event that terminates the lives of an estimated 10% of patients with schizophrenia

(11,

13).

This article considers our current conceptualizations of depression-like symptoms in patients with schizophrenia, documents their common occurrence, and reviews the differential diagnosis of conditions that such symptoms might reflect. It also presents a potential integrating model that may facilitate the understanding of depression in at least some individuals with schizophrenia. Last, this article explores the implications for treatment as we enter a new era in schizophrenia pharmacotherapy occasioned by the advent of the so-called atypical antipsychotic agents.

The Stress-Vulnerability Model as a Potential Integrating Concept

The well-known stress-diathesis model of schizophrenia

(77,

78) depicts the psychosis of schizophrenia as a final common path of neuropsychiatric decompensation. The central notion is that vulnerability to schizophrenic psychosis occurs on a continuum in the population, from a tiny fraction of persons with such a strong vulnerability that psychosis is virtually inevitable to the overwhelming majority of the population in whom the vulnerability is so slight that the risk of psychosis is virtually negligible. In between, there is a small, yet meaningful, portion of individuals who could become psychotic if stressed enough but who could also survive without psychosis if not sufficiently stressed.

The stress in this model can be biological or psychosocial, and many relevant stresses have been described. Intrauterine viral infection, poor prenatal nutrition, birth injuries, and childhood head trauma would all be examples of early-life biological stressors. Substance abuse is an example of a biological stressor occurring more proximally to a first or subsequent psychotic episode. Traumatic interpersonal experiences, more longitudinal psychic stresses (such as chaotic, abusive, or high “expressed emotion” environments), and lack of opportunity to develop adequate compensating coping skills are examples of psychosocial stressors.

It is provocative to speculate that the activation of an affective diathesis, such as depression, could act as a sufficient stressor precipitating psychosis in people with otherwise modest vulnerabilities. Certainly depression is a highly stressful state psychologically, and it is possible that it is stressful in relevant biological ways as well (e.g., insomnia, hormonal changes, neurotransmitter effects). And since within the vulnerability continuum there are many more people with moderate than with extreme vulnerabilities, a reasonable percentage of manifest psychotic episodes could be precipitated by depressive episodes in individuals otherwise only moderately vulnerable to psychosis. If this is the case, it might help to explain some of the “depression” seen in the course of schizophrenia, including, notably, the depression-like symptoms observed early in the course of some psychotic decompensations. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that dysphoria is associated more with positive symptoms than with negative symptoms in schizophrenia

(79,

80). It might also help explain the finding that maintenance antidepressant treatment, administered for the purpose of averting depressive relapses in schizophrenic patients with histories of syndromal postpsychotic depression, also seemed to reduce their rate of psychotic exacerbations

(81).

Depression in Schizophrenia and “Atypical” Antipsychotics

The advent of so-called atypical antipsychotic agents may be ushering in a new or “third” era with regard to dealing with schizophrenia. The first era was the preneuroleptic epoch, during which many detailed descriptions contributed to our understanding of the natural history of schizophrenia. After neuroleptic agents were introduced in the 1950s, it quickly became apparent that a remarkable curtailing of many dramatic psychotic manifestations was possible, even if many negative or cognitive symptoms persisted. Subsequently, almost all patients were treated with these agents, both acutely and in routine maintenance. A new and at least somewhat milder condition resulted: neuroleptic-treated schizophrenia. It was during this second era that most studies of “depression in schizophrenia” were undertaken, which form the basis of our current recognition and understanding of this condition.

There are several reasons to suspect that schizophrenia treated with atypical antipsychotics may prove to be at least a somewhat different condition than schizophrenia treated with conventional neuroleptics from the point of view of depression, although this, of course, still needs to be confirmed by appropriate careful investigations. First, atypical antipsychotic agents have a greatly reduced extrapyramidal side effect profile

(82–

86). Since akinesia and akathisia figure prominently in the differential diagnosis of what appears as depression in schizophrenia, this issue alone could be responsible for a notably different expression of depression in schizophrenia. Second, since atypical agents seem to rely much less exclusively on dopaminergic blockade for their therapeutic activity

(83,

87–

90), they might circumvent the mechanism of neuroleptic-induced dysphoria that could contribute to the depression syndrome. Third, atypical antipsychotics have frequently been reported to be superior to standard neuroleptics in the treatment of negative symptoms

(83–

86,

91–

96), which can sometimes appear similar to depression.

Either through effects on negative symptoms or by some other means, atypical antipsychotics may lead to superior outcomes for patients with schizophrenia, as suggested by quality-of-life measures

(97,

98). In this event, both acute and chronic reactions to disappointment or stress may be reduced. It is also possible that at least some atypical antipsychotic agents (so far demonstrated clearly only for clozapine in the treatment of refractory schizophrenia) may be superior to standard neuroleptics in the treatment of psychosis itself

(93,

99). If this is the case, depression associated with the prodrome of psychotic relapse might possibly be reduced. Another mechanism whereby psychotic relapse may be averted through atypical antipsychotic use is by means of better medication compliance

(95,

100–

102), perhaps on the basis of a more favorable side effect profile

(83,

85,

86,

103). Last, it is possible that atypical antipsychotic agents have direct antidepressant activity on their own.

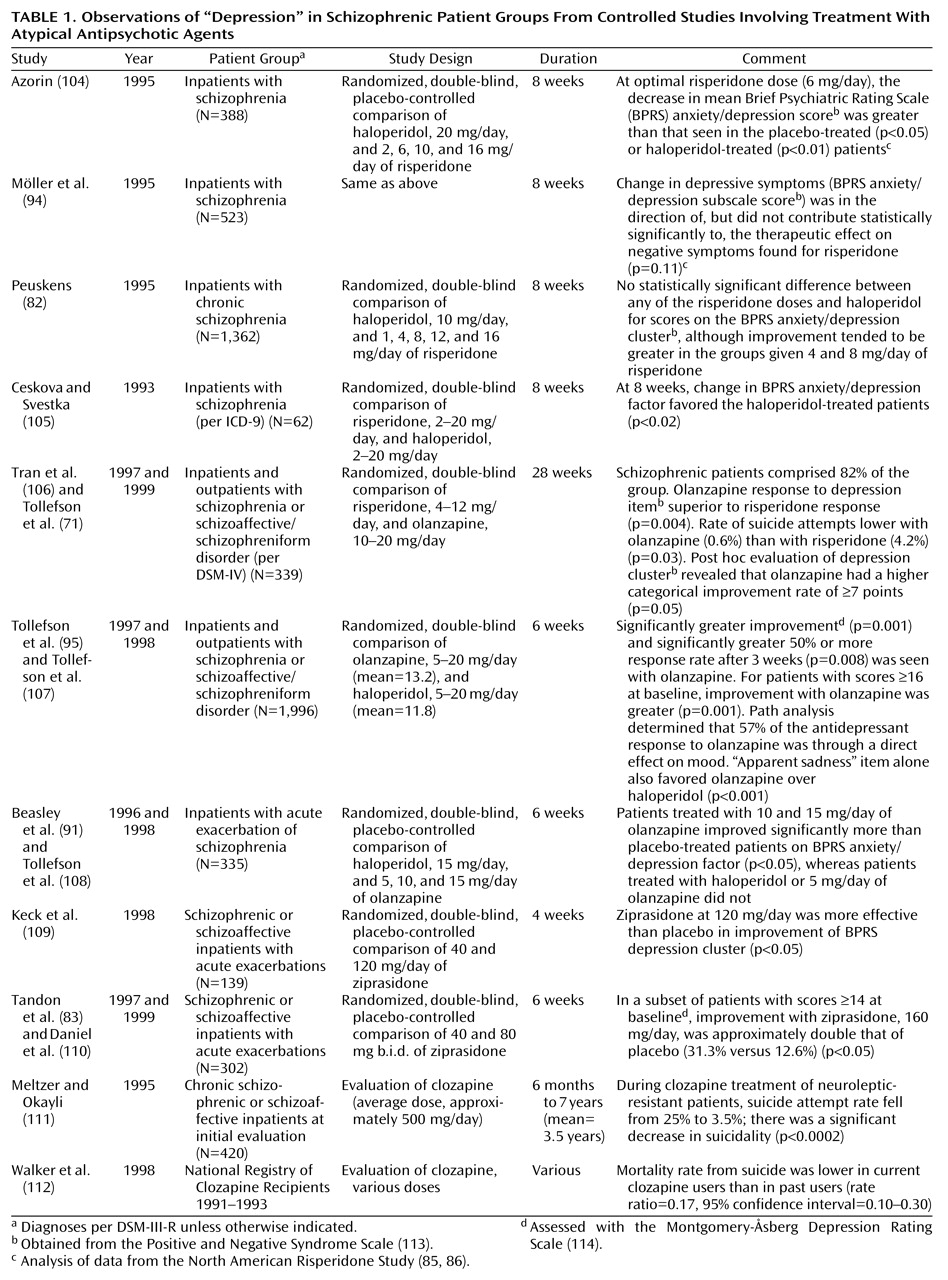

Table 1 reviews the controlled studies of atypical antipsychotic agents that make reference to the issue of depression. Several of these suggest a benefit for atypical antipsychotic agents in this regard. It is relevant to note, in this context, that conventional neuroleptics themselves have been found to have at least some degree of antidepressant activity

(42,

107,

115–

119), perhaps particularly in patients with agitated depression. Indeed, it may be features of agitation or excitement within the depression syndrome that may be particularly helped by atypical antipsychotics as well

(120,

121), although studies have not been specifically designed to tease this out definitively. In addition to the studies cited in

Table 1, a number of anecdotal reports also suggest that the atypical antipsychotics have superior antidepressant properties or, in the case of clozapine, antisuicidal properties when compared with conventional neuroleptics

(87,

122–

129), with but a single study suggesting the contrary

(105).

Obviously, combinations of any or all of these effects could potentially be responsible for more favorable depression profiles in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics versus conventional neuroleptics. Further research is needed to clarify the shape and size of such an effect and to probe its possible mechanisms. Nevertheless, as summarized in

Table 1, the controlled observations to date are intriguing with regard to potentially reduced rates of depression-like morbidity among schizophrenic patients receiving atypical antipsychotics.

Thirteen of the studies in

Table 1 either are, or are reanalyses of, prospective randomized trials. Twelve of the 13 present evidence, of various strengths, that olanzapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone may have an antidepressant spectrum of activity in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. No published study could be found that tested the activity of quetiapine in this regard. One trial

(105), the smallest of the group, presented data suggesting that risperidone may be inferior to haloperidol in terms of BPRS anxiety/depression factor improvement. Whether this result has to do with the relatively high dose range of risperidone employed (as much as 20 mg/day) or the lower dose range of haloperidol (as low as 2 mg/day) compared to the other studies is unclear. Altogether, eight of the studies in

Table 1 used haloperidol as a comparison medication. The possibility, however, that extrapyramidal side effects of haloperidol created a spurious impression of superior antidepressant activity for the atypical antipsychotics in these studies is lessened by the sophisticated path-analysis examination in the largest of the studies

(95,

96,

107). One study suggested that olanzapine was superior to risperidone in alleviating depression

(71), and two studies found ziprasidone to be superior to placebo

(83,

109). The final two studies in

Table 1 present evidence suggesting that suicidality may be reduced in patients receiving clozapine. Suicidality is not a direct measure of depression, and other factors such as psychotic disorganization or terror can also be associated with self-destructive behavior in this population. However, it is not unreasonable to speculate that suicidality can still serve as a logical, although imperfect, proxy for depression in schizophrenia, especially since it represents such an important negative outcome.

The broad array of affinities for receptor sites attributable to the novel atypical antipsychotic agents (including a wide array of 5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT], dopamine [other than D

2], and muscarinic sites as well as α

1-noradrenergic and histamine-1 receptor sites) suggest a variety of potential mechanisms through which atypical antipsychotics might exercise antidepressant effects

(107,

130). Interest in both depression

(131) and schizophrenia

(132) has focused on the 5-HT

2 binding site, but it would be premature to conclude that this is the key or exclusive site of action, and more research is needed. Useful clues in this area may also be gleaned from the existing experience involving the use of tricyclic antidepressants as adjunctive agents in the treatment of depression in schizophrenia

(14). An extended consideration of mechanistic biochemical issues concerning depression, schizophrenia, and atypical antipsychotic agents goes beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that there are many differences in receptor level activity among the different atypical antipsychotic agents that may prove to be relevant to their eventually being found to have differing clinical antidepressant profiles. They therefore should not necessarily be considered to be a homogeneous group of agents nor should the effect—or lack of effect—found with one agent necessarily be assumed to apply to other atypical agents.

Treatment Strategies

A rational approach to treating depression in schizophrenia flows from considering the differential diagnosis. Excluding organic etiologies, the first consideration concerning a newly emergent depressive reaction in schizophrenia is whether it is a transient reaction to disappointment or stress or the prodrome of a new psychotic episode. The most prudent initial response is to increase surveillance and provide additional nonspecific support. A transient reaction to disappointment or stress will soon resolve spontaneously, and an incipient psychotic episode will soon declare itself. In the latter case, the increased surveillance will allow the best chance for the new episode to be detected promptly and “nipped in the bud” by appropriate interventions with antipsychotic medication.

If an episode of depression persists in a patient treated with a conventional neuroleptic, the question next arises whether the neuroleptic medication is responsible for the depression-like symptoms, either as an extrapyramidal side effect (akinesia or akathisia) or as a form of direct neuroleptic-induced dysphoria. There are three ways that such a situation could be approached: 1) neuroleptic dose reduction, if there is leeway to accomplish this safely; 2) introduction or upward titration of an antiparkinsonian medication (likely to be useful for akinesia but less likely for akathisia), a benzodiazepine, or β blocker (the latter two being likely to be useful for akathisia

[133]); or 3) substitution of an atypical antipsychotic for the conventional neuroleptic.

If the episode of depression persists in a patient already being treated with an atypical antipsychotic, the existing literature gives less guidance. Again, dose reduction is a possibility if there is leeway for this, especially if the antipsychotic agent is risperidone, which has at least a modest degree of parkinsonian side effects in the higher dose range

(88). Antiparkinsonian medication is another option, especially in conjunction with risperidone for the same reason. Anticholinergic antiparkinsonian medication may be an interesting option as well, since it is possible that it has its own antidepressant activity

(27,

134) or anti-negative-symptom action

(135). However, an anticholinergic antiparkinsonian agent would not be likely to be a felicitous choice in a patient receiving clozapine, since the combined anticholinergic activity might lead to too great a risk of autonomic side effects. Substituting one atypical antipsychotic agent for another is an additional possibility.

In antipsychotic-treated schizophrenic patients who are not flagrantly psychotic, persisting episodes of depression that do not respond to antiparkinsonian agents may respond to the addition of an adjunctive antidepressant medication

(4,

14,

136–

139). Most of the literature supportive of this intervention has focused on conventional neuroleptic-treated outpatients receiving adjunctive tricyclic antidepressants

(4,

6,

14). The study that was most positive involved full syndromal depression criteria and continued antiparkinsonian medication throughout the antidepressant trial

(136). It is certainly plausible, however, that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants would be useful as well, and some early results support this

(140,

141). Adjunctive monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) might also be useful for depression in schizophrenia, although the literature is sparse

(142). It is of further interest that there have been some encouraging results involving adjunctive SSRIs

(140,

141, 143–

147), MAOIs

(141,

148–

150), and trazodone

(151) in double-blind trials treating negative symptoms in schizophrenia. No prospective randomized study has yet been published, however, involving an adjunctive antidepressant added to an atypical antipsychotic agent in depressed patients with schizophrenia. Also of interest is that, although it may well be useful, ECT has not been specifically studied in the treatment of depression in patients with schizophrenia.

Additionally, lithium may be a useful adjunct in at least some cases of depression in schizophrenia, although definitive trials have not been published. Most reports concerning the use of lithium in schizophrenia have focused on its acute use during psychotic exacerbations rather than its extended use during maintenance-phase treatment

(138,

152). The indicators most frequently cited in the literature as being of favorable prognostic significance for lithium response in schizophrenia have been excitement, overactivity, and euphoria. Nevertheless, depressive symptoms have occasionally been suggested as features indicative of a favorable adjunctive lithium response in schizophrenia

(153). Other favorable prognosticators mentioned for lithium response in schizophrenia are the presence of previous affective episodes, a family history of affective illness, and an overall episodic nature to the clinical course

(154).

Finally, although the focus of treatment discussed in this article has been primarily pharmacologic, any discussion of treatment strategies for depression in schizophrenia is incomplete without consideration of psychosocial interventions. Appropriately controlled studies of psychosocial interventions are, of course, notoriously complex and have not been carried out in a specifically depressed schizophrenic population. But this does not mean that they are not useful. There is little doubt that appropriately applied psychosocial strategies, such as stress reduction, psychoeducation, skill-building, problem-solving techniques, and family interventions designed to minimize excessive expressed emotion can be helpful

(155). Strategies that foster hope, confidence, and self-esteem and interventions that contribute to real-life success experiences may be quite beneficial as well.