The relationship between dissociative disorders and trauma is well established. However, individuals with seemingly comparable traumas may differ greatly in the extent to which they dissociate, and it has become increasingly apparent in recent years that various factors in addition to the actual trauma play a role in the development of trauma-related psychopathologies. A stress-diathesis model has been proposed for both posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and dissociative disorders, as only about 25% of exposed individuals develop PTSD and the proportion who develop dissociative disorders is not known

(1,

2).

PTSD risk factors have been identified, but much less is known about factors predisposing to dissociative symptoms; high hypnotizability or suggestibility may be one risk factor

(2). In a study examining the relationship between personality and dissociation in general psychiatric patients and healthy subjects, dissociation scores were predicted by the character traits of low self-directedness and high self-transcendence but not by temperament traits

(3). In a community sample, mature defenses were found to correlate with low dissociation scores

(4). A twin study failed to identify a genetic contribution to pathological dissociation, but, again, a general population sample rather than a sample of patients with dissociative disorders was studied

(5).

We were interested in examining personality factors associated with dissociation. Such personality traits might predispose traumatized individuals toward developing or maintaining dissociative symptoms, or, conversely, trauma and dissociation might contribute to the fixation of certain personality traits. Personality can be conceptualized as a mélange of heritable temperament and experience-shaped character, although this model is oversimplified because both temperament and character are probably partly determined by complex variations in genotypes and neurochemical profiles and partly modifiable

(6,

7).

In this study we examined depersonalization disorder, one of the major dissociative disorders, for which a link to childhood interpersonal trauma has been shown

(8). Regarding temperament, we hypothesized that individuals prone to behavioral inhibition would be more likely to “shut down” and dissociate when traumatized. With regard to character we used a psychodynamic model and a cognitive model and hypothesized that more primitive defenses and cognitive schemata reflecting major disruptions in attachment would be associated with dissociation.

Method

Fifty-three subjects with DSM-IV-defined depersonalization disorder and 22 healthy comparison subjects were consecutively recruited from several depersonalization research protocols for which written informed consent was obtained. Subjects were evaluated by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders

(9). Healthy comparison subjects were free of dissociative disorders, other lifetime axis I disorders assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders

(10), and axis II disorders assessed by the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality

(11). All subjects completed the Dissociative Experiences Scale

(12), a 28-item self-report trait measure of dissociation, and a depersonalization subscore of the Dissociative Experiences Scale was also calculated

(13).

Temperament was measured by using Cloninger’s Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire

(14), a 100-item self-administered instrument that yields three temperament dimensions. Novelty seeking is the tendency to seek out novel cues, reward dependence is the tendency to strongly respond to and seek out rewards, and harm avoidance is the tendency to respond strongly to aversive stimuli and show behavioral inhibition.

Defenses were measured by using Bond’s revised 88-item version of the Defense Style Questionnaire

(15), which has been factor analyzed into three levels of defenses

(16). Mature defenses such as sublimation and anticipation reflect highly functional adaptation. Neurotic superego-type defenses such as undoing and reaction formation are less adaptive. Immature defenses such as projection and acting out result in denial of reality and poor adaptation.

Cognitive schemata were measured by using the Schema Questionnaire, a 205-item self-report instrument that yields three higher-order factors

(17). Cognitive schemata are enduring structures at the core of an individual’s self-concept that develop during early relationships with significant others. Disconnection schemata reflect defectiveness and emotional inhibition and subsume themes of abuse, neglect, and deprivation. Overconnection schemata involve impaired autonomy with themes of dependency, vulnerability, and incompetence. Exaggerated standards schemata reflect self-sacrifice, perfectionism, and exaggerated self-expectations.

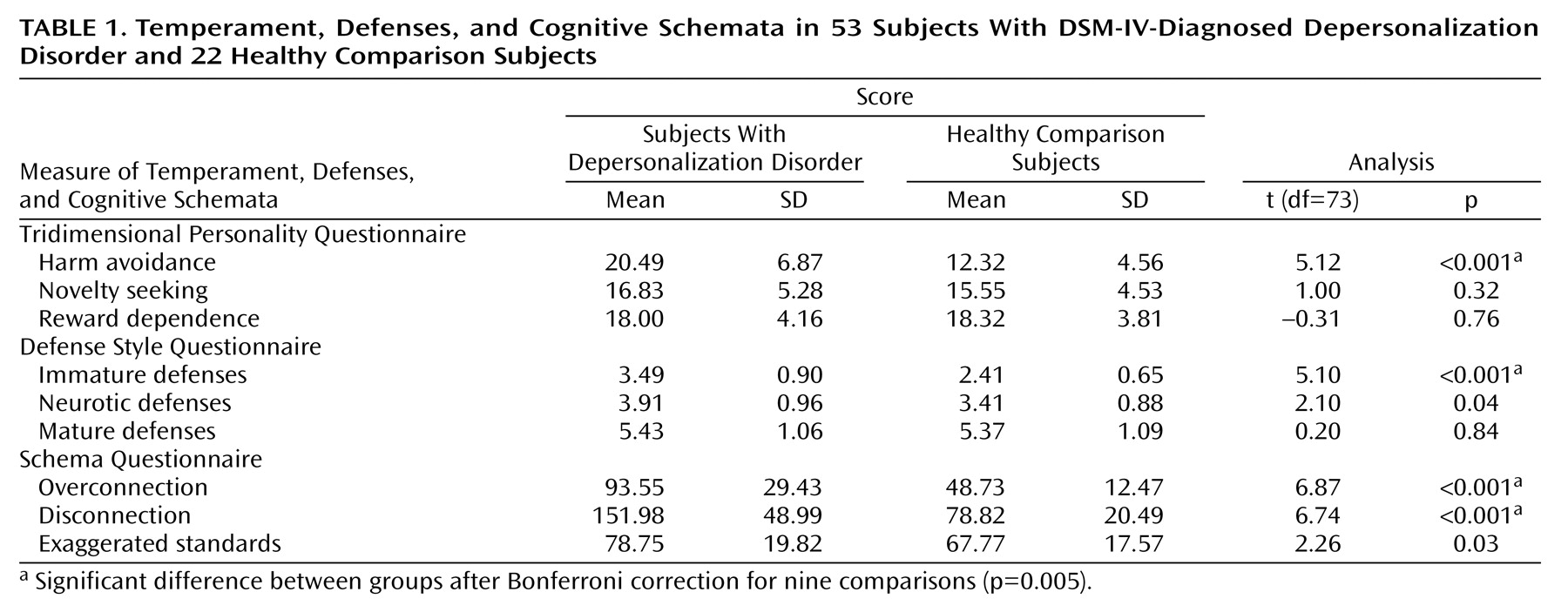

Thus, the study examined a total of nine variables, three from each instrument (

Table 1). Between-group comparisons employed Student’s t tests, Bonferroni-corrected for nine comparisons. Within the group of subjects with depersonalization disorder, we computed Pearson’s correlations between dissociation scores and personality variables, applying a conservative 0.01 level of significance.

Results

The two groups did not differ in age (mean age of the subjects with depersonalization disorder was 34.38, SD=10.21, versus mean=29.82, SD=7.06, for the comparison subjects) (t=1.91, df=73, n.s.) or gender (25 of the subjects with depersonalization disorder were women, compared with 13 women in the group of healthy subjects) (χ2=0.88, df=1, n.s.). Dissociation scores were higher in the group of subjects with depersonalization disorder (mean=21.5, SD=12.7, versus mean=3.9, SD=3.2) (t=6.40, df=73, p<0.001), as were depersonalization scores (mean=43.6, SD=20.6, versus mean=2.6, SD=3.2) (t=9.23, df=73, p<0.001).

Table 1 shows that the scores for harm avoidance, immature defenses, and overconnection and disconnection cognitive schemata were significantly greater in the subjects with depersonalization disorder than in the comparison subjects. Within the group of subjects with depersonalization disorder, dissociation scores significantly correlated with harm avoidance (r=0.36, df=51, p=0.009), immature defenses (r=0.61, df=51, p<0.001), disconnection (r=0.49, df=51, p<0.001), and overconnection (r=0.41, df=51, p<0.001). Depersonalization scores were significantly correlated with overconnection (r=0.40, df=51, p=0.003). All correlations among harm avoidance, immature defenses, overconnection, and disconnection were significant (p<0.01), with the exception of the correlation between harm avoidance and immature defenses.

Discussion

These findings support the hypothesis that several personality factors are associated with pathological dissociation. Specifically, harm-avoidant temperament, immature defenses, and overconnection and disconnection cognitive schemata were highly prevalent in the subjects with depersonalization disorder and, furthermore, were quantitatively related to the severity of dissociation.

We are not able to determine on the basis of our findings whether these personality correlates of dissociation play a causal role in its genesis, contribute to its perpetuation over time, or become fixed aspects of personality as a result of trauma and dissociation. A longitudinal design is needed to address such temporal relationships.

Other limitations include the use of self-report instruments, the absence of comparison psychiatric groups, and the inclusion of a single dissociative diagnosis. However, the validity of the instruments used is widely established, and the findings are robust. The Defense Style Questionnaire immature factor includes 12 defenses, and dissociation is just one, represented by three of 46 questions; therefore, the finding of prevalent immature defenses in the group of subjects with depersonalization disorder is not tautological. The poorly investigated topic of dissociative diatheses merits further study.