Journalism can be a hazardous profession. During 2001 alone, 100 journalists were killed and many hundreds imprisoned and maltreated

(1). While the majority were local journalists, targeted for exposing corruption or expressing political dissent, the names of foreign war correspondents feature prominently among those killed or detained. It should be self-evident that war is dangerous and that those who report on it run the risk of becoming casualties themselves, a point poignantly made by a collection of photographs of the Vietnam war assembled from the work of photographers killed in the conflict

(2). What is new, however, is a perception in the profession that the number of war journalists killed may be on the increase

(3). The recent ambush and murder in Sierra Leone of two of the most respected war journalists shocked the industry and demonstrated that experience, knowledge, and common sense are not guarantees of survival.

Given the dearth of data in relation to war journalists, coupled with concerns that reporting war may be becoming increasingly dangerous, we investigated the extent and nature of psychopathology among those who bring us the news from the world’s conflict zones.

Method

We approached six major news organizations—CNN, BBC, Reuters, CBC, Associated Press, ITN (Independent Television News)—and an organization representing freelance journalists (the Rory Peck Trust) and explained the purposes of the study. All of the organizations agreed to participate and provided 170 names, together with work and e-mail addresses. Only journalists fluent in English and currently covering war were assessed.

First Phase

The first phase of the study involved asking the journalists to complete a series of self-report questionnaires. The itinerant nature of war journalism, the far-flung geographic locations involved, and the fact that postal services frequently stop during periods of conflict made contacting the journalists problematic. To overcome this difficulty, we developed an interactive web site. Each journalist was assigned an individual, confidential identification number that had to be entered to access the web site. The contents of the paper and Internet versions were identical and covered 1) basic demographic data, 2) details of alcohol and illicit drug use, and 3) assessment of PTSD, depression, psychological distress, and personality traits by four self-report questionnaires.

The basic demographic data included the number of years the respondent had worked as a war journalist, the list of wars covered, and past psychiatric history. Attempts at tallying all traumatic events were abandoned given the impracticality of the task. The average duration of time spent in zones of conflict by the war journalists (approximately 15 years) meant that the hazardous events experienced were too numerous to accurately recall. For example, the one war that attracted the greatest number of war journalists was the Bosnian conflict, which lasted many years. Journalists took to living in cities under siege, such as Sarajevo, where their attempts at reporting or filming the news often exposed them daily to life-threatening situations.

A unit of alcohol was defined as a regular-size bottle of beer, a glass of wine, or a shot of spirits. Fourteen units of alcohol per week for men and 9 units for women were considered the upper limits of acceptable weekly intake

(15).

The Impact of Event Scale—Revised

(16) contains 22 questions that closely follow the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD. Thus, the questionnaire contains three subscales for intrusive (reexperiencing), avoidance, and hyperarousal phenomena. We followed the rating scale instructions by asking subjects to indicate symptoms that occurred during the past 7 days only and were related to traumatic, dangerous, or disturbing life experiences. Given the many wars covered by the group, we did not specify any particular conflict or event but allowed the journalists to chose single, multiple, or no events, as they deemed suitable. We did, however, ask the journalists to specify what events had been most troubling to them. For all the war journalists, the events chosen related to their war exposure.

The Beck Depression Inventory-II

(17), which contains 21 mood-related questions, was used to assess depression. It provides a choice of four responses per question and is scored in a Likert fashion (the possible scores are 0, 1, 2, 3).

The 28-item General Health Questionnaire

(18) contains four subscales, each with seven questions, describing symptoms of somatic complaints, anxiety, social dysfunction, and depression, respectively. A choice of four responses is provided for each question. The subscale scores are summed to give an overall index of psychological distress. A simple Likert scoring method (possible scores of 0, 1, 2, 3) was used as this is preferred for detecting between-group differences in subscale scores.

Second Phase

The second phase of the study involved direct interviews. The difficulties in contacting the group were magnified when it came to direct interviews, and because of time and cost restraints, it was not possible to interview the entire study group. Therefore, a random sample of 20% of the responding journalists were approached for interview. None refused. The interviews took place in New York, London, Paris, Madrid, Barcelona, and Johannesburg. The 28 journalists were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders (SCID)

(19), and the prevalences of PTSD, mood disorders, and substance use disorders (lifetime, current, and before war exposure) were ascertained. The interviewer was blind to the results of the self-report questionnaires.

Comparison Group

Irrespective of setting, there are stressors generic to journalism (e.g., deadlines, “scooping” the competition). To control for these in symptom expression, we assessed a comparison group of nonwar journalists. A group of 107 domestic journalists who did not report on war were approached to undergo the same assessment procedure used with the war journalists. While some in this group also occasionally reported on distressing events (e.g., plane crashes), care was taken to exclude those who had traveled to report on war. Similarly, a random sample of 19 of these journalists (18%) were selected for interview with the SCID. None refused. The interviews were conducted face-to-face or by telephone.

Statistical Analysis

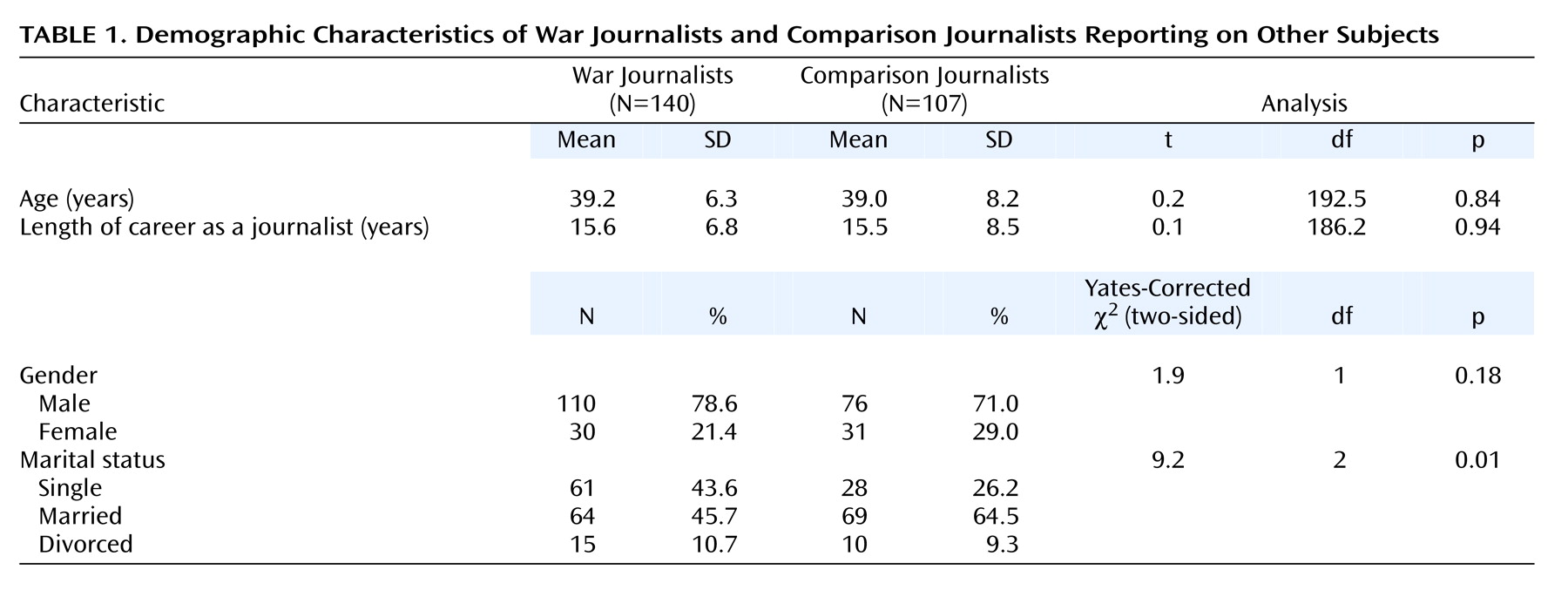

We compared the two groups by using t tests and chi-square analyses. All two-by-two chi-square analyses were two-sided and Yates corrected. If any one cell in a two-by-two analysis had a count of less than 5, a two-sided Fisher’s exact test was used. With respect to between-group t test analyses, the Levene test for equality of variance was applied, and where appropriate, the unequal-variance t values and significance levels were reported. All t tests were two-tailed. To control for multiple comparisons, we applied a Bonferroni correction (0.05/22, setting the significance level at 0.002). Transmitting data from a web site relied on the variable quality of the Internet connection. In a few cases, this resulted in lost data. Since the number of subjects varied slightly between tests, the results are presented with the relevant numbers of subjects.

Consent

Both the paper and Internet versions of the study received ethical approval. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. On the web site, subjects gave consent by clicking on the “I agree” box after reading the descriptive preamble.

Discussion

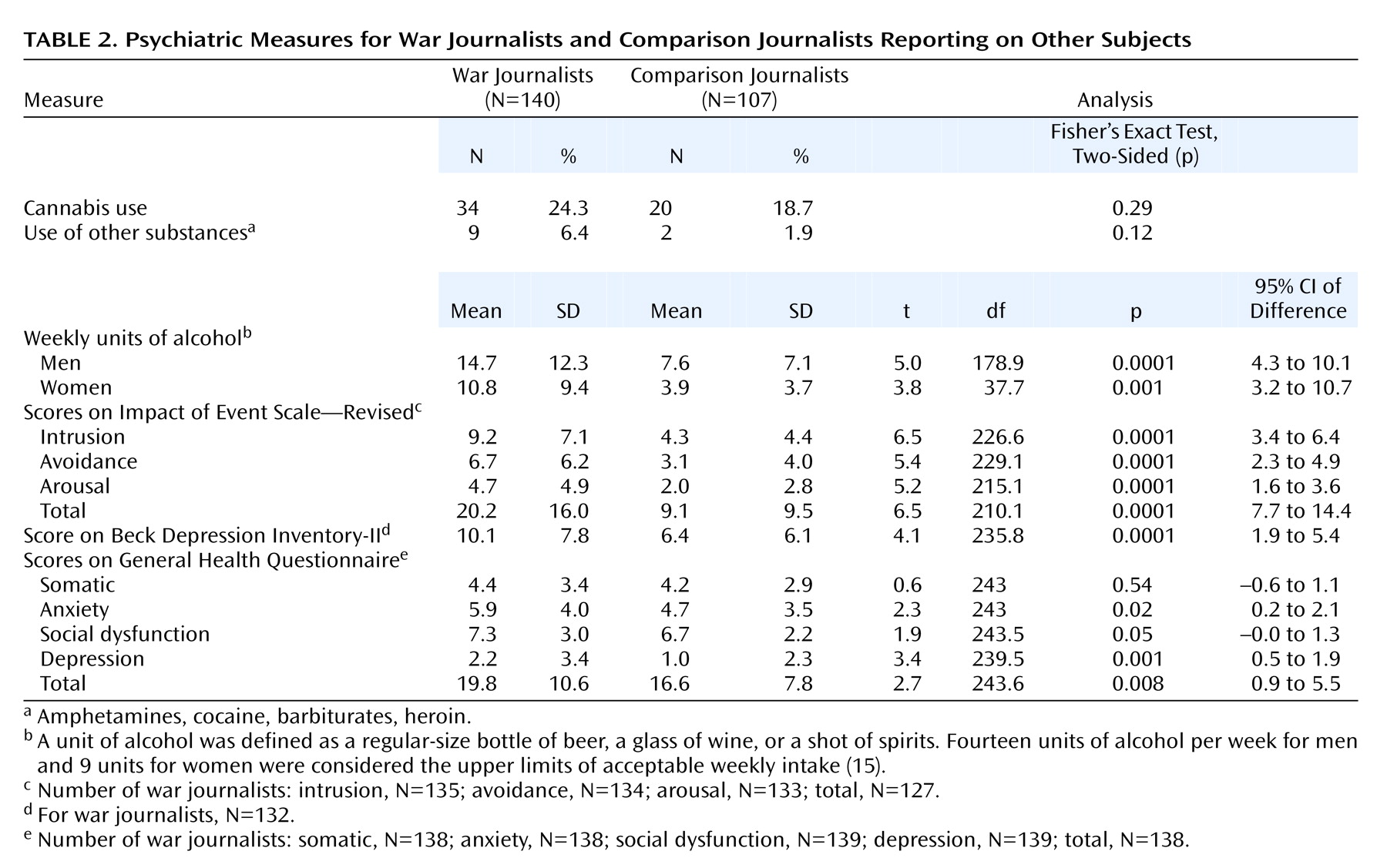

In this study of 140 war journalists, drawn from the world’s major news organizations, we found higher rates of psychopathology than in a demographically matched comparison group of 107 nonwar journalists. Specifically, the war journalists drank more heavily and showed higher rates of PTSD and major depression. They were not more likely to receive treatment for these conditions. Before discussing these results in greater detail, we would like to address the composition of the study group.

Experienced war journalists are relatively few in number. The 170 names forwarded by organizations such as the BBC and CNN represent a sizable segment of those who travel to areas of conflict. Our response rate of greater than 80% therefore suggests our subjects are representative of war journalists in general. The fact they have been reporting wars for, on average, 15 years highlights not only their experience but also our success in capturing the central core of bona fide war journalists, as opposed to those who cover a conflict or two before moving on to less hazardous news work. It is also important to note that while war journalists are never openly forced into covering a particular conflict by their news bosses, it is generally recognized that a pattern of refusing dangerous assignments may have adverse career consequences. Thus, when starting out in their career there is a tendency to accept every war story. Only as established war journalists can they be more selective in choosing when and where they are sent.

A significant number of war correspondents, particularly women, drink excessively, with a weekly alcohol consumption well above that of their nonwar colleagues. However, heavy drinking did not necessarily translate into a diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence as defined by DSM-IV. The lifetime prevalence of alcohol abuse did not differ from that in the general population

(20). While heavy drinking may not have rendered the majority dysfunctional with respect to their work, it does leave the individual at risk for a host of long-term medical problems

(15).

Results from all self-report measures of PTSD and depression revealed higher scores in the war group. While useful as screening instruments, self-report questionnaires cannot by themselves generate psychiatric diagnoses. Furthermore, the Impact of Event Scale—Revised, Beck Depression Inventory-II, and General Health Questionnaire provided indices of current symptoms only. These two limitations do not, however, apply to a structured clinical interview, such as the SCID. The fact that only one in five war journalists could be interviewed was due solely to logistical difficulties. The 28 journalists selected at random were scattered over three continents during the course of the study, and it often took months to finally connect and complete the process. Nevertheless, the clinical interviews corroborated the finding of significant psychopathology in approximately one-quarter of the group.

Of the 28 war journalists interviewed, all had been shot at numerous times, three had been wounded (of whom one had been shot on four separate occasions), three had had close colleagues who were killed while they were working together on assignments, two had been subject to mock executions, two had had bounties placed on their heads, one had survived a plane crash (the pilots were killed) only to be subsequently robbed by soldiers who looted the wreckage, and two had had close colleagues who committed suicide. Given these descriptive details, higher scores on the Impact of Event Scale, an index of PTSD, were not unexpected in the war group. While symptoms from all three subscales were frequently endorsed, intrusive and hyperarousal symptoms, i.e., unwanted recollections of specific events accompanied by hypervigilance and autonomic arousal, were more common than avoidance phenomena. Of note was the fact that the avoidance item “I stayed away from reminders of the trauma” was endorsed least often. Rather, the avoidance pattern incorporated such maladaptive strategies as “My feelings about it were kind of numb” and “I felt as if it hadn’t happened.” Thus, despite deeply troubling recollections of events witnessed, the war journalists returned constantly to the scenes of old or new traumas, a pattern of behavior sustained over many years. This could contribute to their high lifetime prevalence of PTSD, i.e., 28.6%. In addition, the fact that PTSD, in all but one case, developed after the journalists began working in war zones suggests a strong connection between the dangers confronted in war and the development of psychopathology.

It is noteworthy that the lifetime prevalence of PTSD in war journalists exceeds the 7%–13% reported for traumatized police officers

(21,

22) but is equivalent to

(23) or less than

(24) figures for combat veterans, depending on the source cited. Such comparisons, while placing the result within a comparative frame of reference, are nevertheless misleading. Soldiers and policemen receive extensive training to deal with violence. War journalists do not. In recognition of this deficiency, innovative trauma education programs for journalists in training have begun to be offered by some universities

(25).

The high PTSD figures are matched by the rates for major depression. Once again, the figures for the war group are substantially higher than those for the comparison group. With the structured interview, the lifetime prevalence of major depression in the war group was 21.4%, which exceeds the 17.1% rate reported for the general population in the United States

(20). If one removes the one subject whose major depression predated work in war zones, the prevalence drops to 14.3%. However, it is important to note that the U.S. data are made up of equal numbers of male and female subjects, and the latter have a lifetime prevalence of 21.3%, almost double the approximately 12% in males. In our predominantly male study group, even after we controlled for the cases predating war exposure, the result still translates into a lifetime prevalence of major depression above that in the U.S. National Comorbidity Study

(20). The high comorbidity of major depression and PTSD in this study is in keeping with figures from trauma studies of other population groups

(26,

27).

With the stringent Bonferroni correction factor applied to the data, the results from the 28-item General Health Questionnaire essentially confirmed the preceding finding with respect to depression. This instrument was used previously as an index of psychological distress in trauma settings

(28,

29). The higher total scores in the war journalists were driven mostly by elevated depression scores and, to a lesser extent, symptoms of anxiety and social dysfunction.

The interviews with 20% of the group revealed that war journalists are profoundly affected by their symptoms of PTSD. While we had no clear way of judging the effects of the syndrome on the quality of their work, every war journalist with PTSD spoke of considerable social difficulties, such as an inability to adjust to life back in a civil society, a reluctance to mix with friends, troubled relationships, the use of alcohol as a hypnotic, and embarrassing startle responses that led to social avoidance. With such difficulties, they fulfilled the DSM-IV criterion that specifies that the symptoms must cause “significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning.”

Perhaps our most telling observation was that despite greater levels of psychopathology than in the comparison group, the war journalists were not more likely to have received help, be it pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy. The clear implication is that many war journalists are not receiving treatment for their PTSD, depression, and alcohol abuse. The reasons for this are many and varied and not the subject of the present study. However, this observation together with the fact that we have found no previous research on this topic speak to a culture of silence on the part of the news bosses and the journalists themselves.

This last point touches on an intriguing question: What motivates war journalists to return to situations of extreme peril, particularly when almost one in four have suffered from PTSD at some point in their careers? While we plan to report this separately, a few comments are called for here. The first salient observation is that, until recently, discussing psychological distress within the profession was discouraged. A prevalent view was that to be a war journalist you had to have the “right stuff.” An admission of emotional distress in a macho world was feared as a sign of weakness and a career liability. Ambition, coupled with a belief that war reporting enhances a career by giving a high media profile, left journalists reluctant to speak out about their fears and insecurities. Many chose to suffer in silence. The recent death of two celebrated war journalists on assignment in Sierra Leone (mentioned earlier) was, in part, the catalyst for a reappraisal of these views. Another, lesser factor that could have contributed to repeated exposure to trauma despite adverse consequences is the psychological naiveté inherent in some members of the profession. A number of journalists interviewed were deeply unhappy, prey to symptoms of PTSD and depression, but surprisingly unaware of what afflicted them. Thus, while giving articulate voice to subjective distress, a diagnosis such as PTSD was for the most part unknown. Such naiveté is also consonant with a belief that as a profession they can go off to war and emerge psychologically unscathed. This denial may be a necessary, albeit distorted prerequisite allowing war journalists to venture repeatedly into situations of grave physical danger.

We believe that our study is the first to explore the psychological status of war correspondents. As such, the results need replicating, more so as we were able to interview only one in five journalists. While we did not find strong evidence that psychopathology in the war group predated their exposure to war, the limited number of subjects suggests this question may not be definitively answered here. However, our findings that PTSD may affect a quarter of war journalists and that they have a high lifetime prevalence of major depression deserve serious consideration. These disorders adversely affect quality of life

(30) and may tend toward chronicity if left untreated

(31). The data should therefore come as a wake-up call to the news organizations that all is not necessarily well with the men and women who, at considerable risk, bring us news of the world’s conflicts.