Epidemiological studies of mental disorders in the general population have found strong associations with reduced health-related quality of life, diminished productivity, absenteeism, unemployment, and high levels of health care utilization

(1–

9). The World Health Organization Global Burden of Disease study estimated that in 1990, 10% of all disability worldwide was attributable to neuropsychiatric disorders

(10). Depression alone, a common, underrecognized, and treatable condition, has been predicted to become the second leading cause of worldwide morbidity over the next two decades

(11,

12).

The U.S. military provides a unique opportunity to examine the burden of mental disorders in one of the healthiest segments of the U.S. population, an ethnically diverse population with equal access to comprehensive medical care. The 1.4 million service members on active duty in the U.S. military represent approximately 1% of the entire working adult population between the ages of 18 and 45 in the United States. We are not aware of any population-based studies to date addressing the rates of inpatient and ambulatory mental health care utilization across this important population. This is surprising, given the availability of one of the largest and most comprehensive integrated health utilization data systems. Data have been systematically collected on all hospitalizations among active-duty personnel since 1990 and on ambulatory visits since 1996. Electronic personnel records exist for the entire population, providing excellent demographic-specific denominator data. With very few exceptions (detailed later), active-duty personnel receive all of their inpatient medical care from military facilities, which provide services without cost to these individuals.

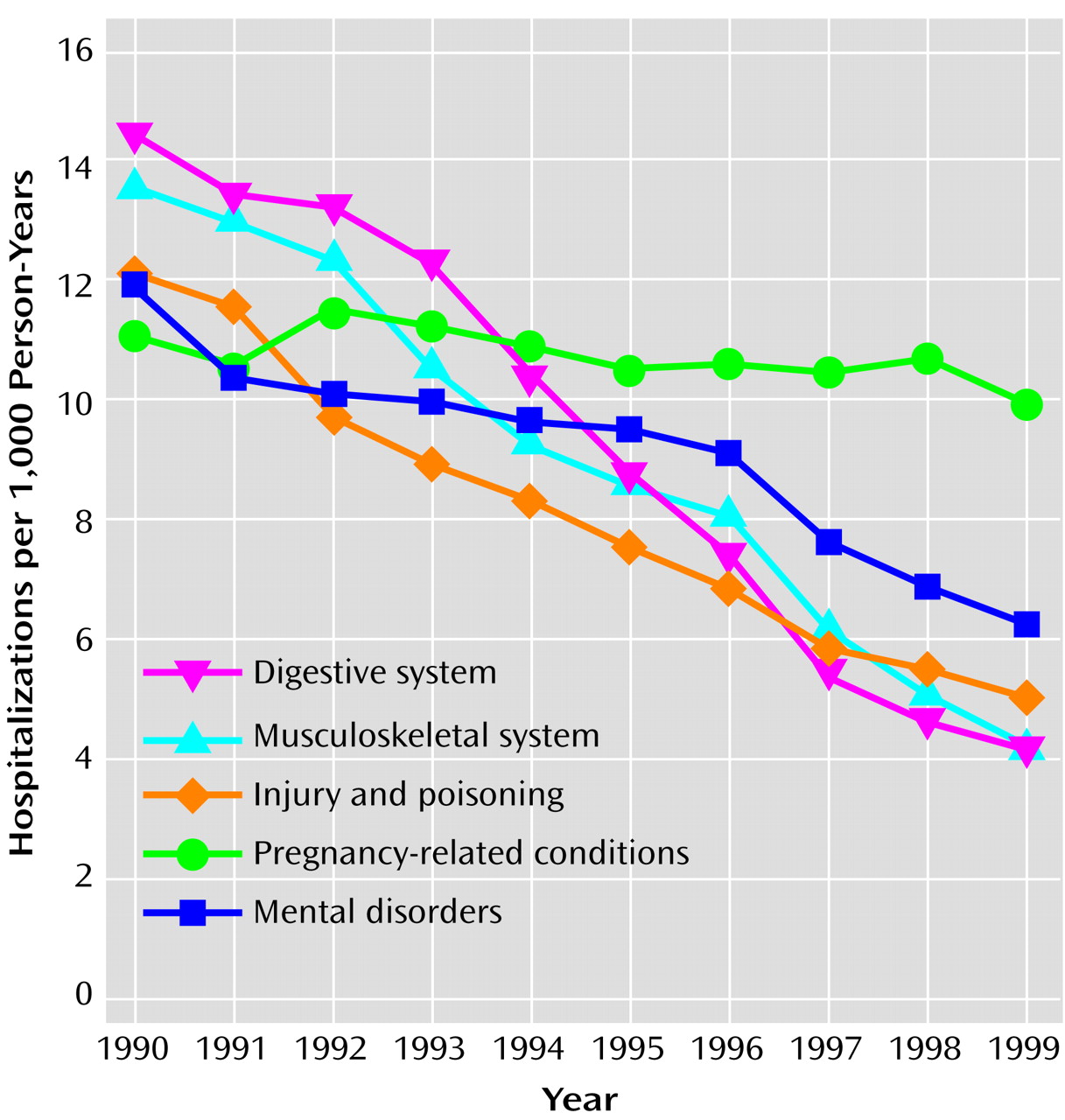

The objective of this study was to estimate the burden of mental disorders on the utilization of health care and on occupational functioning as measured by attrition from military service. We compared rates of hospitalization, hospital bed days, and outpatient visits related to mental disorder discharge diagnoses with those for 15 other major medical illness categories. Rates of hospitalization and ambulatory visits were examined over a 10-year (1990–1999) and a 4-year (1996–1999) period, respectively, across the entire military. We also examined the relationship of health care service use for mental disorders and career duration. Attrition rates (discharge from active-duty military service) after the first encounter for a mental disorder were compared with attrition rates after a first encounter for other medical illness categories. This study represents one of the largest published sources of population-based data on the impact of mental disorders on health care utilization and occupational functioning in a well-defined healthy working population.

Method

Surveillance Methods and Data Analysis

We conducted population-based analyses of hospitalizations occurring at U.S. military medical facilities between 1990 and 1999 among active-duty personnel from all four branches of service (Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines). The source of the data was the Defense Medical Surveillance System, which is an integrated database that includes demographic and health care utilization data for all military personnel who have been on active duty for at least 1 month. This information system is operated by the Army Medical Surveillance Activity, which routinely collects and analyzes medical surveillance data for policy makers and military health care providers

(13). Defense Medical Surveillance System denominator data are obtained from the Defense Manpower Data Center (Monterey Bay, Calif.), which maintains up-to-date records on all personnel, including demographic data (age, gender, race) and service-related data (such as date of entry into service, date of separation from service, and occupation). These data are updated monthly, thus allowing longitudinal cross-sectional analyses.

Health care utilization data were obtained from all permanent U.S. military medical facilities worldwide. For all hospitalizations at military medical facilities, an electronic record, the Standard Inpatient Data Record, is generated at the time of discharge. These records include dates of admission and discharge, discharge diagnoses coded by using the ICD-9-CM, and personal identifiers that allow integration with the personnel (denominator) data files. Up to eight discharge diagnoses are recorded for each hospitalization. The Defense Medical Surveillance System receives updates of the Standard Inpatient Data Record records on a monthly basis. The accuracy of military inpatient electronic data has been shown to be comparable to that of other large health services information systems in the civilian sector

(14,

15). One study demonstrated excellent agreement between the principal ICD-9 mental disorder diagnoses recorded in the electronic records and those determined by independent blinded psychiatric review of the hospital records (kappa=0.80–0.95)

(15). While most inpatient care among active-duty service members is provided at military facilities, some hospitalizations occur at civilian facilities during emergencies or in remote locations where no military facility is available. However, admissions to civilian facilities, which are tracked by the military health system, accounted for less than 2% of all psychiatric hospitalizations among active-duty personnel in the 1990s and thus were not included in this analysis.

A new system for data on ambulatory care became available in 1996, but it took more than a year for all facilities to become automated. An estimated 60%–70% of facilities were reporting in 1997, and the most complete data were available for 1998 and 1999. Available ambulatory data include date of visit, ICD-9 diagnoses (up to four allowed), and personal identifiers. These records are electronically transmitted to the same facility that collects the inpatient data and are updated monthly and provided to the Defense Medical Surveillance System.

This is a descriptive study that used the entire active-duty military population as the denominator in calculating rates, with rates expressed as a function of total person-years of surveillance. Consequently, statistical tests of differences between population subgroups were used sparingly, both because the study included the entire population, rather than a sample, and because the enormous population size made virtually all comparisons statistically significant, whether or not they were clinically or epidemiologically important.

Classification of Disorders

The following categories of disorders were specified for comparison purposes by using ICD-9 codes (shown in parentheses): infectious and parasitic (001–139), neoplasms (140–239), endocrine/nutrition/metabolic/immunity (240–279), blood and blood-forming organs (280–289), mental disorders (290–319), nervous system and sense organs (320–389), circulatory (390–459), respiratory (460–519), digestive (520–579), genitourinary (580–629), complications of pregnancy/childbirth/puerperium (630–679), skin/subcutaneous tissue (680–709), musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (710–739), congenital (740–759), symptoms/signs/ill-defined conditions (780–799), and injury/poisoning (800–999). For most comparisons in this study the mental disorder category was compared with the 15 other ICD-9 illness categories.

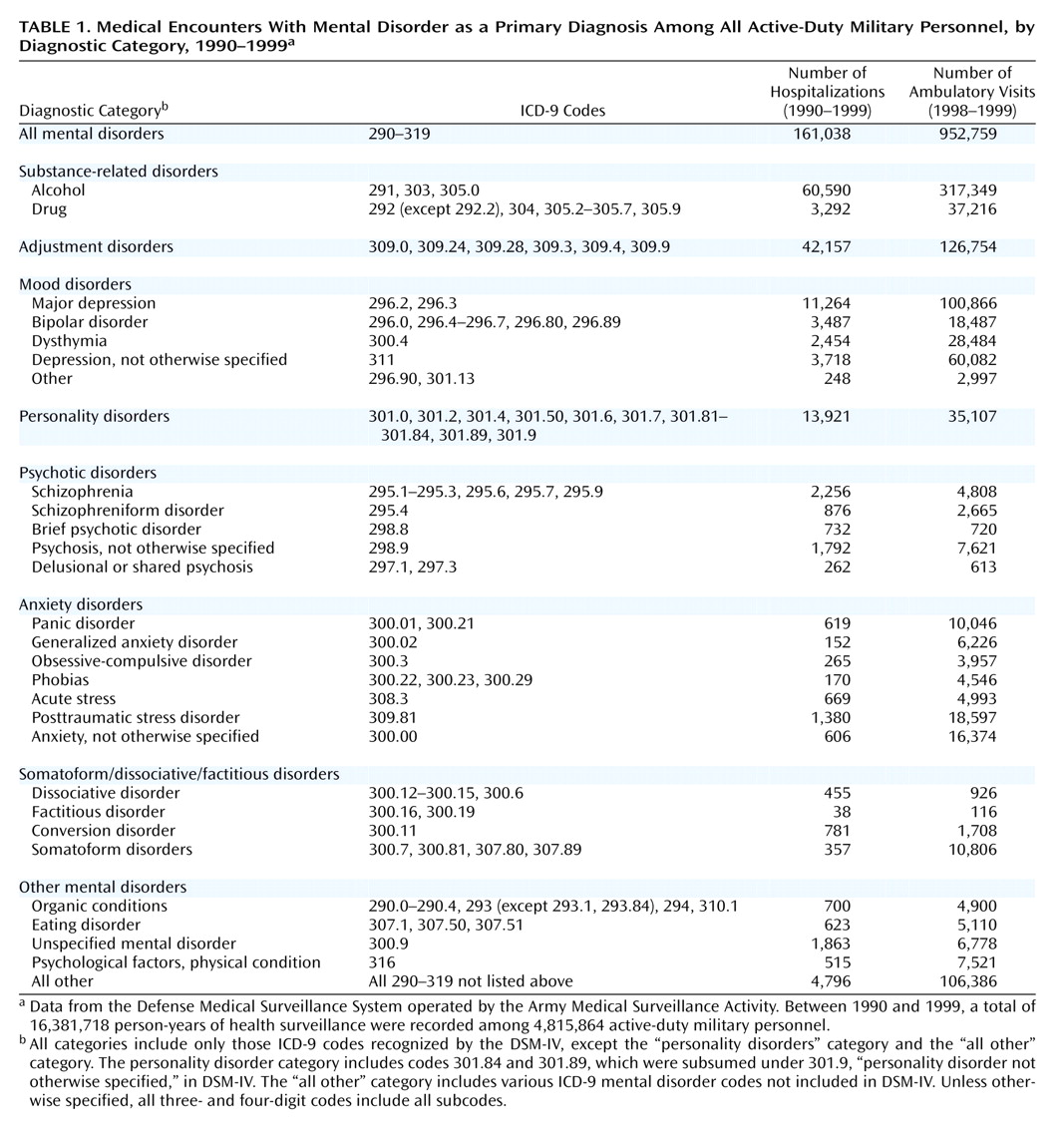

The ICD-9 mental disorder category was further subdivided into eight broad diagnostic categories and additional subcategories, based on how the codes were used in DSM-IV. These eight categories were substance-related disorders, adjustment disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, psychotic disorders, anxiety disorders, somatoform/dissociative disorders, and other mental disorders. The ICD-9 codes used to define each of these categories are shown in

Table 1. Except for the codes for personality disorders and other mental disorders, only those ICD-9 codes that matched disorders listed in DSM-IV were included. The personality disorder category included only those ICD-9 codes included in DSM-IV plus two additional codes, 301.84 and 301.89, which were included in earlier versions of DSM and were subsumed under 301.9 (personality disorder not otherwise specified) in DSM-IV. The additional codes were included because the study spanned several years before and after the publication of DSM-IV. The “other mental disorder” category included a variety of DSM-IV codes (such as those for delirium, dementia), as well as all other codes within the ICD-9 mental disorder category that are not included in DSM-IV.

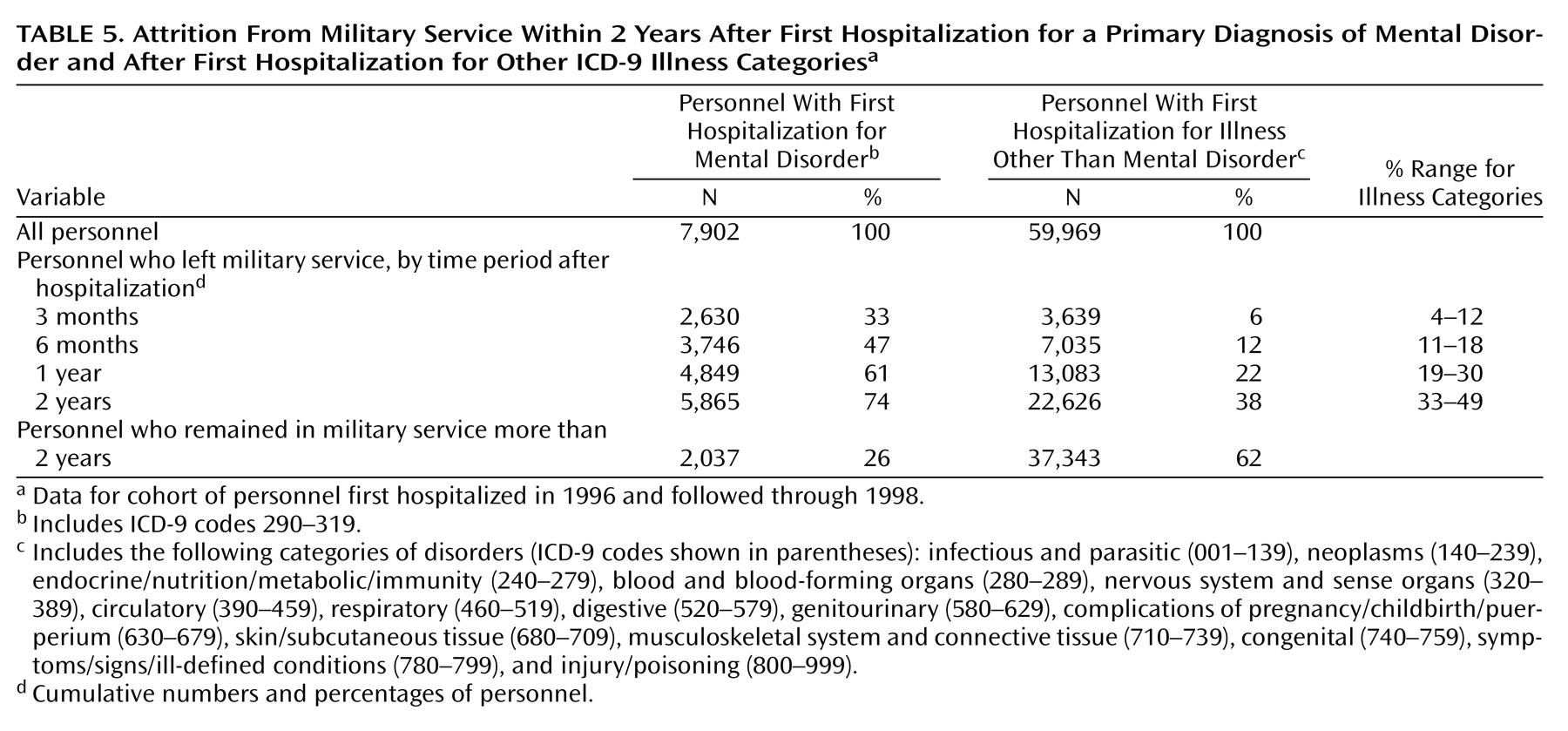

Attrition From Military Service

To determine the relationship between hospitalization for a mental disorder and subsequent attrition from military service, analysis was conducted on data for a cohort of all military personnel hospitalized for the first time in 1996. All individuals in this cohort were followed for 2 years or until the date they left active military service. Rates of attrition were computed for all major diagnostic categories on the basis of the date of first hospitalization in 1996. Attrition rates after the first recorded ambulatory service use in 1997 (the first year for which reasonably complete data were available) were also compared between groups. Statistical comparisons were made by using the chi-square test, with Mantel-Haenszel correction.

Discussion

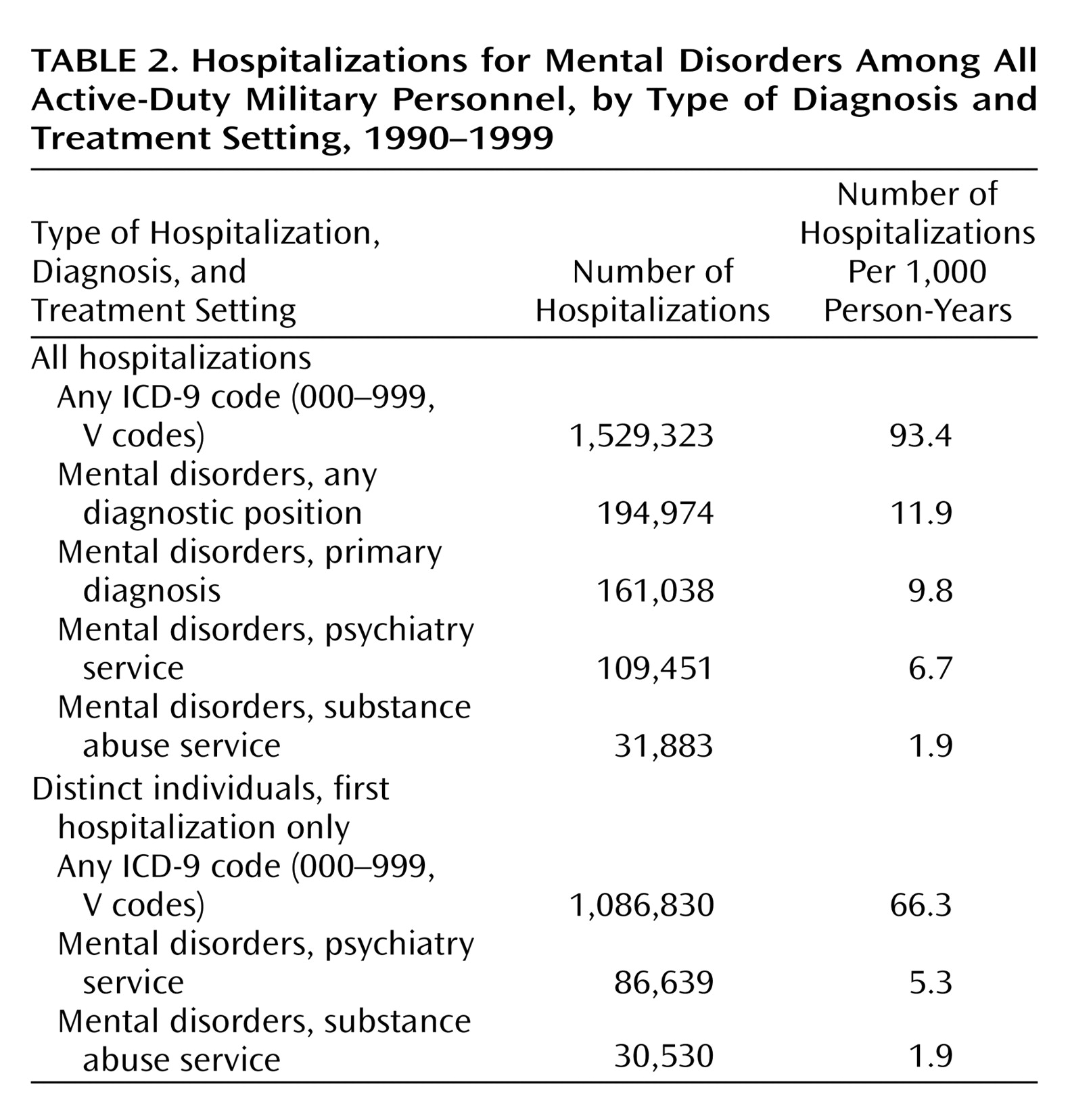

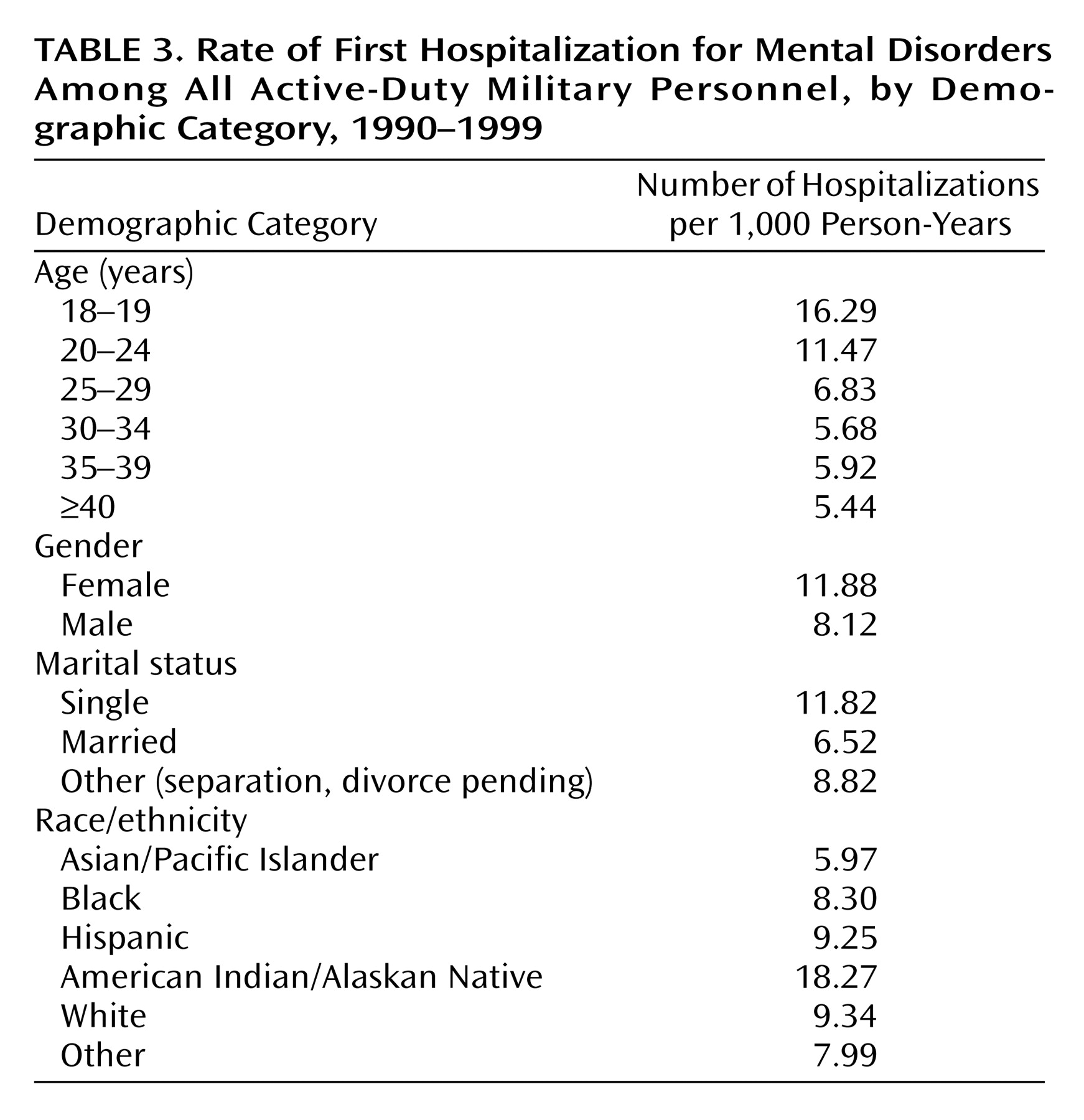

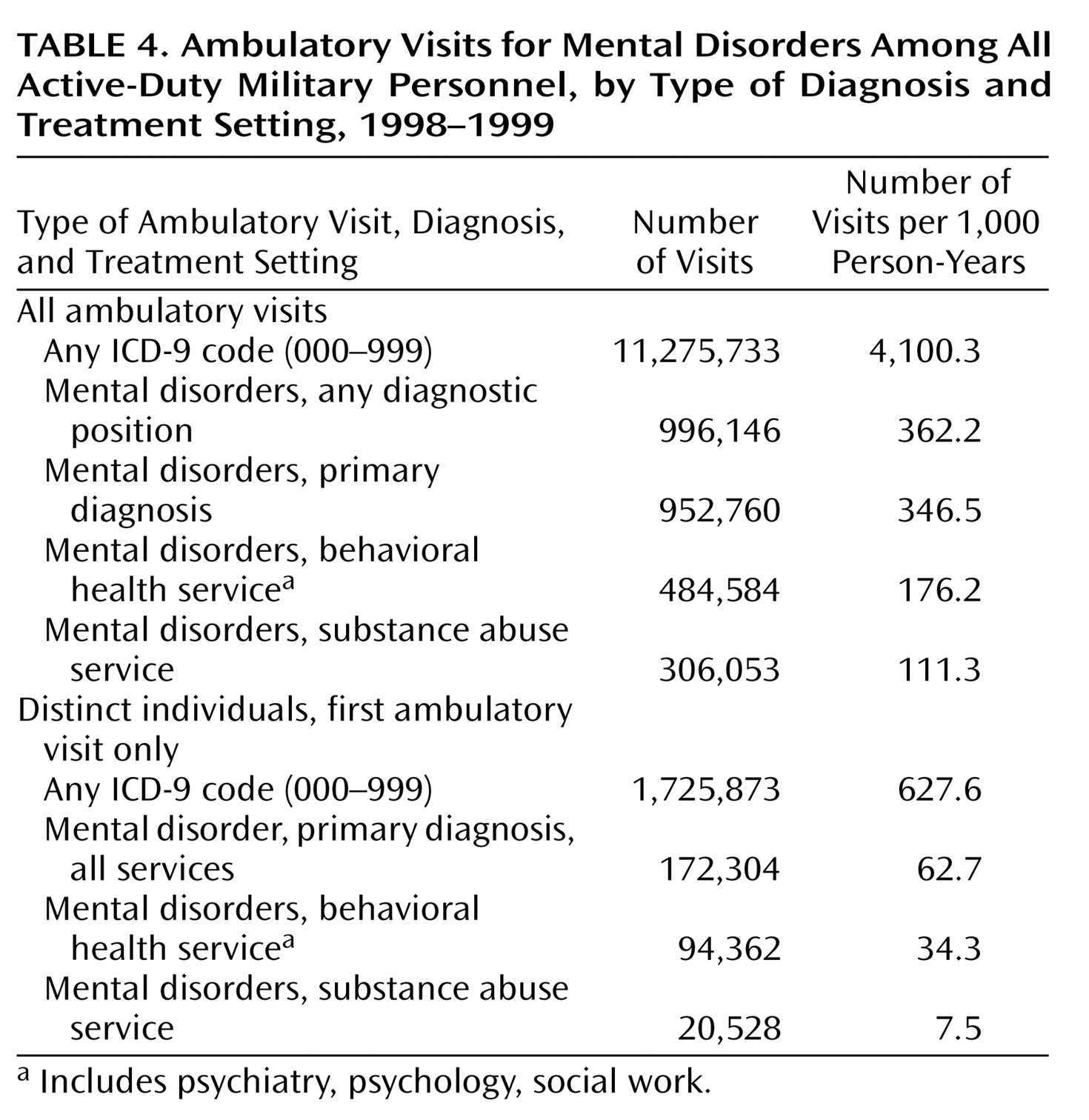

This work represents one of the largest studies that directly compared rates of health care utilization for mental disorders with other disease categories in a large, predominantly young adult working population with equal access to medical care. The U.S. military represents approximately 1% of the entire U.S. adult working population between the ages of 18 and 45 (∼0.5% of women and 2% of men in this age group). Our analyses confirm that mental disorders are a major public health problem and a leading cause of occupational dysfunction in this population. Mental disorder diagnoses were involved in 13% of all hospitalizations, and these hospitalizations accounted for nearly a quarter of all inpatient bed days among active-duty military personnel. For the last 5 years of the study, mental disorders were the second leading hospital discharge diagnostic category. Alcohol and substance use disorders, adjustment disorders, mood disorders, and personality disorders were the most common diagnoses. More than 6% of the entire active-duty population was reported to have received outpatient treatment for a mental disorder annually in 1998 and 1999.

The fact that mental disorders shifted to become the second leading ICD-9 discharge diagnostic category during the 1990s suggests that these disorders were relatively resistant to managed care strategies compared with other illness categories. However, additional factors may have influenced health care utilization trends for mental disorders in the military, including stresses of military life, efforts to destigmatize treatment for mental illness, and improved case-finding and diagnosis. In addition, secular trends in rates of mental disorders among adolescents

(16–

18) may have counterbalanced managed care measures in this predominantly young adult population. Although younger age and female gender were associated with higher rates of mental disorder hospitalizations in this study, there was no evidence of major demographic changes in the military over the study period that could account for the observed trends.

In what way does this study add to the existing literature, and how generalizable are these data to civilian populations? We are not aware of any other studies that offer such comprehensive population-based mental health care utilization data, especially for a young adult working segment of the population. All studies of mental health care utilization to date have derived estimates by very different methods, such as through surveys of hospitals

(19–

23), community-based surveys such as the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study and the National Comorbidity Survey

(24–

30), and data from insurance organizations

(31,

32). An advantage of our study is that it avoids many potential methodological problems of studies in civilian populations, such as reliance on U.S. census data for denominators, difficulties in clearly defining catchment areas of health care facilities, inequalities in health care coverage or access to medical services, and limitations inherent in any survey design, such as sampling errors, respondent errors, and nonrandom refusals

(27,

33,

34).

Perhaps most comparable with the data in this study are data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey, which involved a sample of hospitals with average lengths of stay of less than 30 days and utilized census data for denominators

(19–

21). For example, in 1996, the rate of hospital discharge for mental disorders (as a primary diagnosis) among persons 15–44 years of age was estimated to be 9.7 per 1,000 persons

(19). This estimate was remarkably similar to the overall annual rate that we measured of 9.8 per 1,000 active-duty personnel, providing strong support for the generalizability of the data from this large military population.

While this is encouraging, more research is clearly needed to refine these comparisons and take into account the complexities of the different health care systems. For example, clinicians in civilian settings may not be reimbursed for treating patients with adjustment disorders, one of the most common diagnostic categories in military populations. There is evidence that factors unique to the military environment, such as limitations in confidentiality and methods of referral, may influence psychiatric diagnostic practices

(35,

36). Although there is no standardized screening instrument for psychiatric disorders used routinely at the time of accession into the military, service members undergo a comprehensive medical evaluation and are unlikely to be accepted into service if they report any significant psychiatric history. This may have an effect on reducing utilization, which would in turn make the estimates of disease burden derived from this study more conservative. Although these examples can be viewed as limitations of this study, they also suggest the opportunity for enormous potential benefits to the military and society of systematic epidemiologic research to further characterize the factors that predict high levels of mental health care utilization. The availability of integrated population-based data systems in the military represents an unprecedented opportunity to define these risk factors while avoiding many of the problems of health services research in civilian populations.

One strength of our study was the opportunity to define utilization patterns in a well-characterized population in which all members have equal access to “free” medical care

(33). One might predict that differences in utilization seen in other studies, such as disparate rates by race/ethnic groups, would not be as apparent in an employed population with equal access to medical services, which is indeed what we found among Caucasians, Hispanics, and African Americans.

Particularly striking was the magnitude of the apparent occupational impact of mental disorders compared with other medical conditions, as measured by attrition from military service. Nearly 50% of personnel hospitalized for the first time for a mental disorder left military service within 6 months, compared with only 12% of those hospitalized for other reasons. This difference was independent of age, gender, or duration of service. Even ambulatory care use for mental disorders was associated with a higher rate of attrition, compared with ambulatory service use for other disease categories.

The reasons for the strong association between health care utilization for mental disorders and subsequent attrition require further study. Our findings raise a number of questions regarding the comparability of military attrition and civilian job loss, and the degree to which military occupational functioning predicts occupational dysfunction in other settings. Clearly, the pathways involving job application, employment, voluntary or involuntary job loss, and disability in association with health care treatment are complex for both military and civilian organizations. One of the limitations of this study is that the data system we used does not provide accurate information about the reasons people left military service. However, it is likely that mental disorders not only contributed to higher rates of medical discharges but to other types of discharges, such as those related to legal, conduct, and behavioral problems and to failure to meet minimum performance requirements. Less likely is an inflation of service utilization due to an incentive to be discharged from service for disability benefits. Many of the mental disorders likely to be diagnosed among service members, including adjustment disorders, personality disorders, and alcohol/substance abuse, are not compensable conditions in military and Veterans Administration disability systems. Disability determinations for other axis I disorders, such as mood disorders and anxiety disorders, depend on many factors in addition to the medical assessment, including the degree of occupational impairment and length of time in military service. Regarding psychotropic medication use, there is no uniform policy prohibiting the use of these medications while on active duty; they are used routinely (especially antidepressants), and such use is not grounds for separation.

The U.S. military remains one of the most highly respected and effective military organizations in the world, and these medical data do not suggest that the impact of mental disorders is greater among service members than in the general U.S. population. Nevertheless, these data speak to the pervasive nature of mental disorders even in the healthiest segment of the population. The impressive difference in attrition rates and the fact that this difference was consistent across inpatient and outpatient services suggest that mental disorders may have a greater adverse influence on occupational functioning than any other medical illness category.