Ataque de nervios (“attack of nerves”) is a culturally defined Latino syndrome usually triggered by acute stress and typically characterized by paroxysms of uncontrollable shouting and crying, trembling, palpitations, and aggressiveness

(1,

2). Although it has a prevalence of 13.8% in Puerto Rico and is considered normal by many Latinos,

ataque is often associated with mood and anxiety disorders

(1). Case reports suggesting that dissociative symptoms are a primary feature of

ataque have never been investigated systematically. These symptoms include depersonalization, amnesia, identity alteration, and trance-like states

(2). In addition, although

ataque has been linked to childhood trauma

(3), the relationship between exposure to trauma and dissociation among

ataque sufferers has not been explored.

Method

Forty adult Puerto Rican psychiatric outpatients were included in the study. Patients with psychotic, organic, or current substance abuse disorders were excluded.

Lifetime number of

ataques de nervios was assessed by using the clinician-rated Explanatory Model Interview Catalogue

(4), which elicits key elements of cultural syndromes. Subjects were coded positive if their self-labeled

ataque de nervios corresponded to the description in the DSM-IV Glossary of Culture-Bound Syndromes. Five ambiguous codings were reviewed along with five unambiguous codings by blinded independent experts. All unambiguous codings were confirmed. Three out of the five ambiguous cases of

ataque were excluded from the data analysis because of idiosyncratic self-labelings inconsistent with typical usage (e.g., “depression attacks”).

Of the remaining 37 subjects,

ataque was coded absent (N=14), present and quantifiable (N=16) (the mean number of

ataques was 4.7 [range=1–15]), or present with extreme frequency (N=7) (number of

ataques was “too many to count”). By dividing subjects with

ataques at the median number of five

ataques, three groups were created for statistical comparisons (

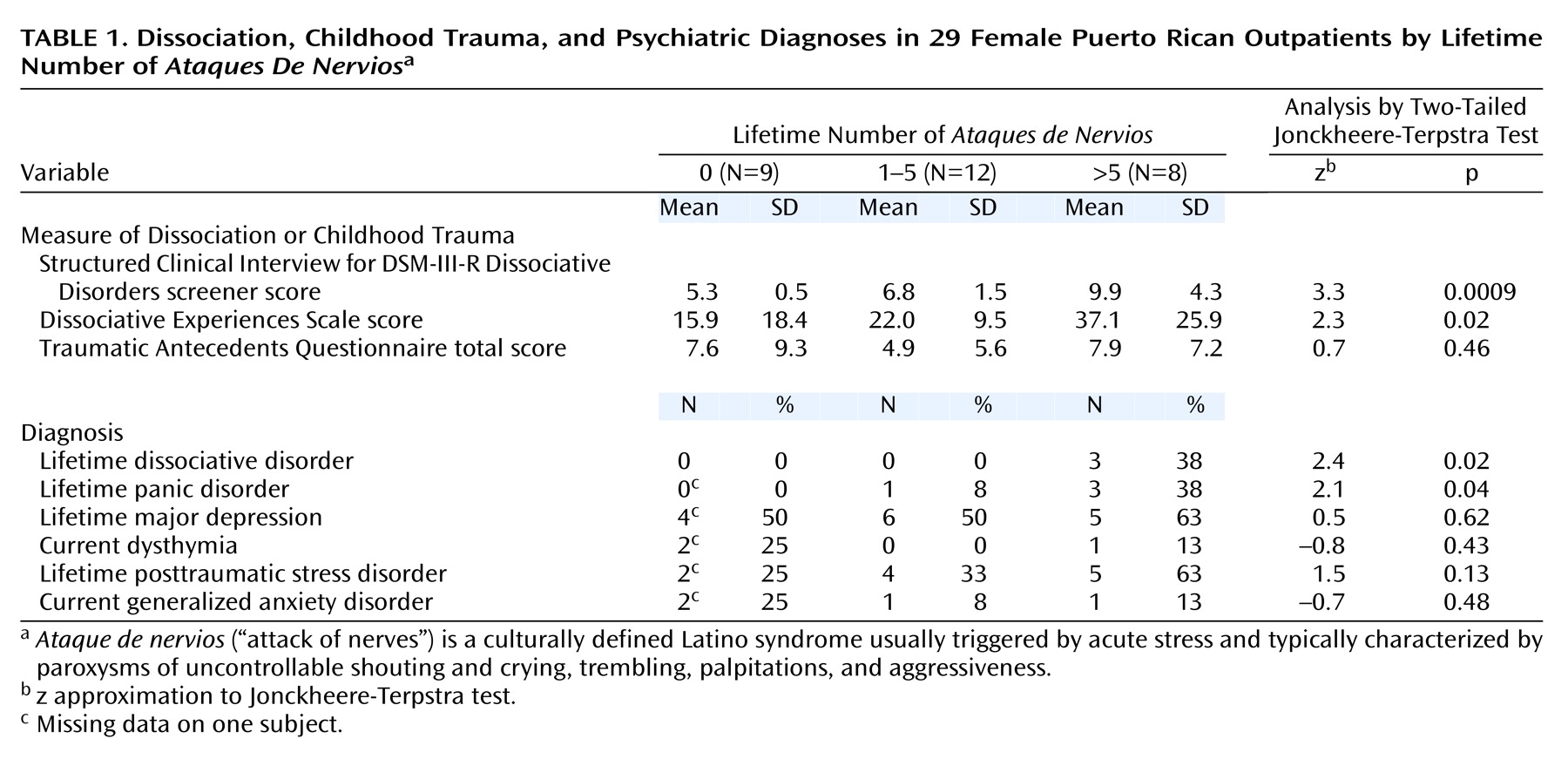

Table 1). Because only eight men were included in the study, data are presented only for the female patients (N=29).

Psychiatric diagnoses for the mood and anxiety disorders associated with

ataque (1) were determined by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Diagnoses of dissociative disorders were determined by using the clinician-rated screening questionnaire of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Dissociative Disorders (SCID-D)

(5), which generates severity scores for five dissociative symptom dimensions and the probability of a categorical diagnosis. Only cases with definite probability were included. Subjects also completed the self-report Dissociative Experiences Scale

(6).

Exposure to trauma before age 18 was ascertained with the clinician-rated Traumatic Antecedents Questionnaire

(7), which provides the sum of eight trauma categories across three developmental stages. A ninth category of “deaths of offspring and child siblings” was added on the basis of clinical experience. According to standard Traumatic Antecedents Questionnaire practice, culturally accepted corporal punishment and uniform household poverty were coded negative, and recurrent abuse by one perpetrator was coded as a single trauma in each developmental stage.

Blind conditions were maintained across all instruments, except between the two SCID interviews. Instruments were administered in Spanish and translated following standard translation methods. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Two-tailed Jonckheere-Terpstra tests

(8) were used to analyze the hypothesized ordered relationship between the outcome variables and

ataque frequency. This test assesses whether the order of the responses relative to the order of the number of

ataques appears random. Demographic variables were analyzed by using analysis of variance.

Results

Linear regression identified a significant interaction between gender and ataque frequency with respect to SCID-D scores (F=7.7, df=1, 31, p=0.009) and Dissociative Experiences Scale scores (F=6.3, df=1, 31, p=0.02), requiring separate analysis by gender. As already noted, data are presented only for the 29 female patients.

All of the women had come from Puerto Rico. Nine had not experienced ataque, 12 had experienced one to five ataques, and eight had experienced more than five ataques. No significant differences were found between the groups in age (mean=47.5, SD=7.8), years of education (mean=7.8, SD=4.9), or age at migration (mean=25.8, SD=10.6).

Dissociative Experiences Scale and SCID-D scores as well as rates of lifetime dissociative disorder and panic disorder showed a significant positive association with number of

ataques (

Table 1). All three women with dissociative disorder had dissociative disorder not otherwise specified.

Traumatic Antecedents Questionnaire total score (

Table 1) and scores for each independent trauma subcategory (data not shown) were not significantly associated with

ataque frequency. Exclusion of the added category for child deaths did not affect the analysis.

After Bonferroni correction for nine comparisons in

Table 1, only the SCID-D scores showed a significant association with

ataque frequency.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first empirical evidence demonstrating a specific relationship between

ataque de nervios and dissociation

(2). Even after correcting for multiple comparisons, clinician-rated dissociative symptoms increased significantly with lifetime

ataque frequency among female Puerto Rican psychiatric outpatients. The fact that the group without

ataques also had mood and anxiety psychopathology suggests that this finding is not solely attributable to the association between general psychopathology and dissociation

(9). The very elevated Dissociative Experiences Scale mean score for the group with more than five

ataques (score=37.1) is similar to scores for patients with dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (score=35.3)

(10), validating our finding of a high rate of dissociative disorder not otherwise specified.

In Puerto Rico,

ataque is twice as prevalent among women as men

(1). Our finding of a gender interaction between dissociative symptoms and

ataque frequency is the first suggestion to our knowledge of a gender difference in

ataque phenomenology. Future research should explore whether this gender interaction signals a sex-specific relationship between dissociation and

ataque.Contrary to our hypothesis, childhood trauma was not associated with

ataque frequency or dissociation. Rather, exposure to trauma was uniformly high across groups

(7), suggesting that, in this group of patients, factors in addition to childhood trauma account for

ataque status. This contradicts previous findings with a different clinical population and trauma scale that showed an association between

ataque and childhood trauma

(3) but is consistent with a multifactorial model of dissociation and

ataque (10). Exposure to trauma was not sufficient to cause frequent

ataques, but whether it was necessary remains unclear.

Before Bonferroni correction,

ataque frequency was associated with panic and dissociative disorders among female patients. This confirms the overlap between

ataque and panic and also validates the concept that

ataque is a more inclusive construct diagnostically

(1). In addition, the very high rate of posttraumatic stress disorder among patients with frequent

ataques, although statistically nonsignificant, should be investigated in larger samples. Taken together, these findings suggest that frequent

ataques are, in part, a marker for psychiatric disorders characterized by dissociative symptoms.

There is no research at present that might inform treatment of this common Latino syndrome. Our study suggests that techniques addressing pathological dissociation might be useful. Future research should continue to investigate the relationship between trauma and dissociation, including cultural factors that might predispose to syndromes such as frequent ataques de nervios.