Psychotropic medications, such as antidepressants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, and psychostimulants, are commonly and increasingly prescribed in both primary care and psychiatric practice settings

(1). No national survey of the rate of use of the different types of psychotropics by HIV-positive patients has been previously reported, to our knowledge. It is estimated that about one-half of HIV-positive patients receiving medical care in the United States suffer from symptoms indicative of mood or anxiety disorders

(2). The importance of identifying and treating depression cannot be overstated. The presence of mood disorders in HIV-positive patients is accompanied by impaired functioning and lower quality of life

(3). Both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy are effective treatments of depression in psychiatric and primary care settings

(4), and treatment can translate into lower medical costs

(5). The efficacy of antidepressant medications has been specifically demonstrated in HIV-positive patients

(6–

8). Anxiolytics, antipsychotics, and psychostimulants are used for the treatment of anxiety, psychosis, mania, and cognitive impairment, respectively

(9,

10). Because HIV-positive patients usually receive a variety of antiretroviral and antibiotic medications, the concomitant administration of psychotropics has implications for possible drug-drug interactions, burden of care, and treatment costs. Thus, data regarding psychotropic use by HIV-positive patients can be informative from various perspectives and relevant to clinicians, pharmacologists, pharmacists, health care administrators, and policy makers.

The HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study surveyed a national probability sample of adults with known HIV infection who received medical care in 1996. Previous analyses of the database have provided information on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and substance abuse

(2), the impact of psychiatric disorders on quality of life

(3), and the use of alcohol, drug, and mental health services by these patients

(11). The purpose of this report is to describe the prevalence and pattern of use of common psychotropic medications among HIV-positive patients receiving medical care in the United States. In addition, we evaluated the relationship between psychotropic use and patient characteristics, such as age, gender, ethnicity, presence of psychiatric disorder, stage of HIV infection, and medical insurance status. Although this study was descriptive, certain specific hypotheses were advanced. It was predicted that psychotropic drug use would be strongly associated with the presence of a psychiatric disorder. Since people with coexisting mental disorders often have more severe symptoms

(12) and are more likely to use multiple medications, it was predicted that comorbidity, defined as the presence of two or more psychiatric disorders in the same patient, would be associated with greater use of psychotropics. Since female and white (non-Hispanic) patients are more likely to be treated for mood and anxiety disorders

(1,

13,

14), higher rates of medication use were predicted for these groups. Since having Medicaid or no health insurance was associated with lower use of health services than having Medicare

(11,

15), lower use of psychotropic medications was expected for patients with Medicaid or no insurance. Possible effects of age and severity of HIV infection were also explored.

Results

Use of Psychotropic Medications

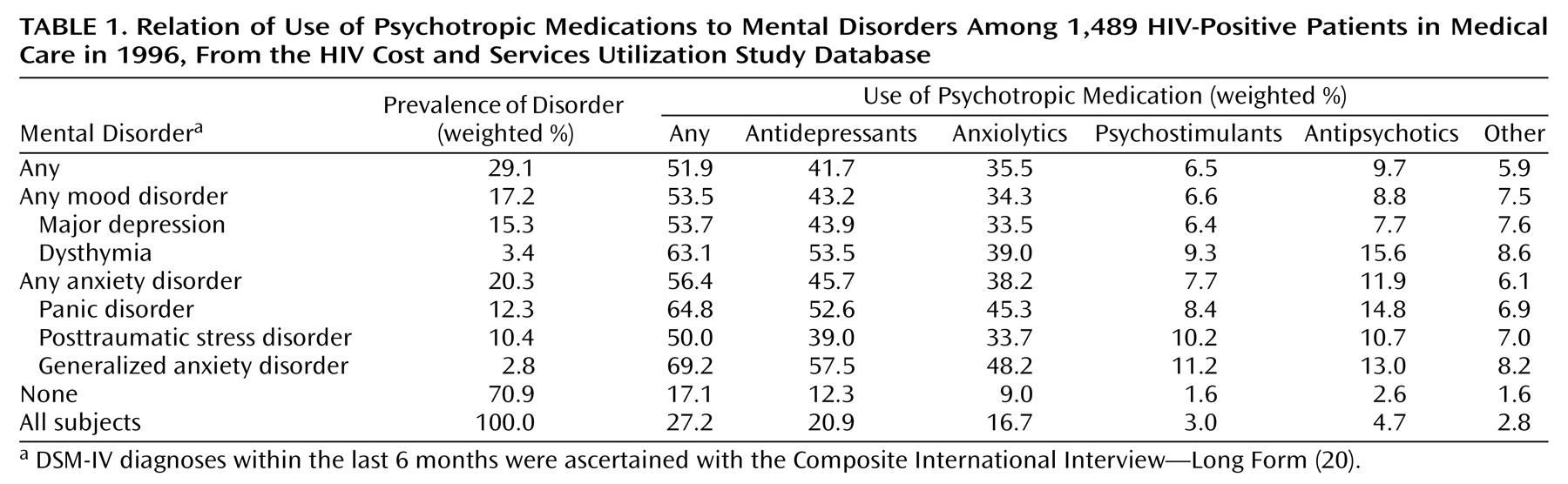

It was estimated that 27.2% of all HIV-positive patients in medical care in the contiguous United States in 1996 received at least one psychotropic drug during the last 6 months before the assessment (

Table 1). Antidepressants were the most commonly used type of psychotropics (20.9% of all patients), followed by anxiolytic medications (16.7%), antipsychotics (4.7%), psychostimulants (3.0%), and other psychotropics (2.8%).

Use of Psychotropics by Mental Disorder

It was estimated that 29.1% of all patients suffered from at least one of the targeted disorders (i.e., major depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) in the 6 months before the interview (

Table 1). The prevalence of anxiety disorders was 20.3%, and that of mood disorders was 17.2%. Major depression was the most common disorder (15.3%), followed by panic disorder (12.3%) and PTSD (10.4%).

Among patients with one or more mood disorders, 43.2% had taken antidepressants and 34.3% had taken anxiolytic medication during the last 6 months. Among patients with one or more anxiety disorders, the estimated use of antidepressants was 45.7%, and that of anxiolytics was 38.2%. Of the patients without a long-form Composite International Diagnostic Interview diagnosis of mood or anxiety disorder, 12.3% received antidepressants, 9.0% received anxiolytics, 2.6% received antipsychotics, and 1.6% received psychostimulant medications (

Table 1).

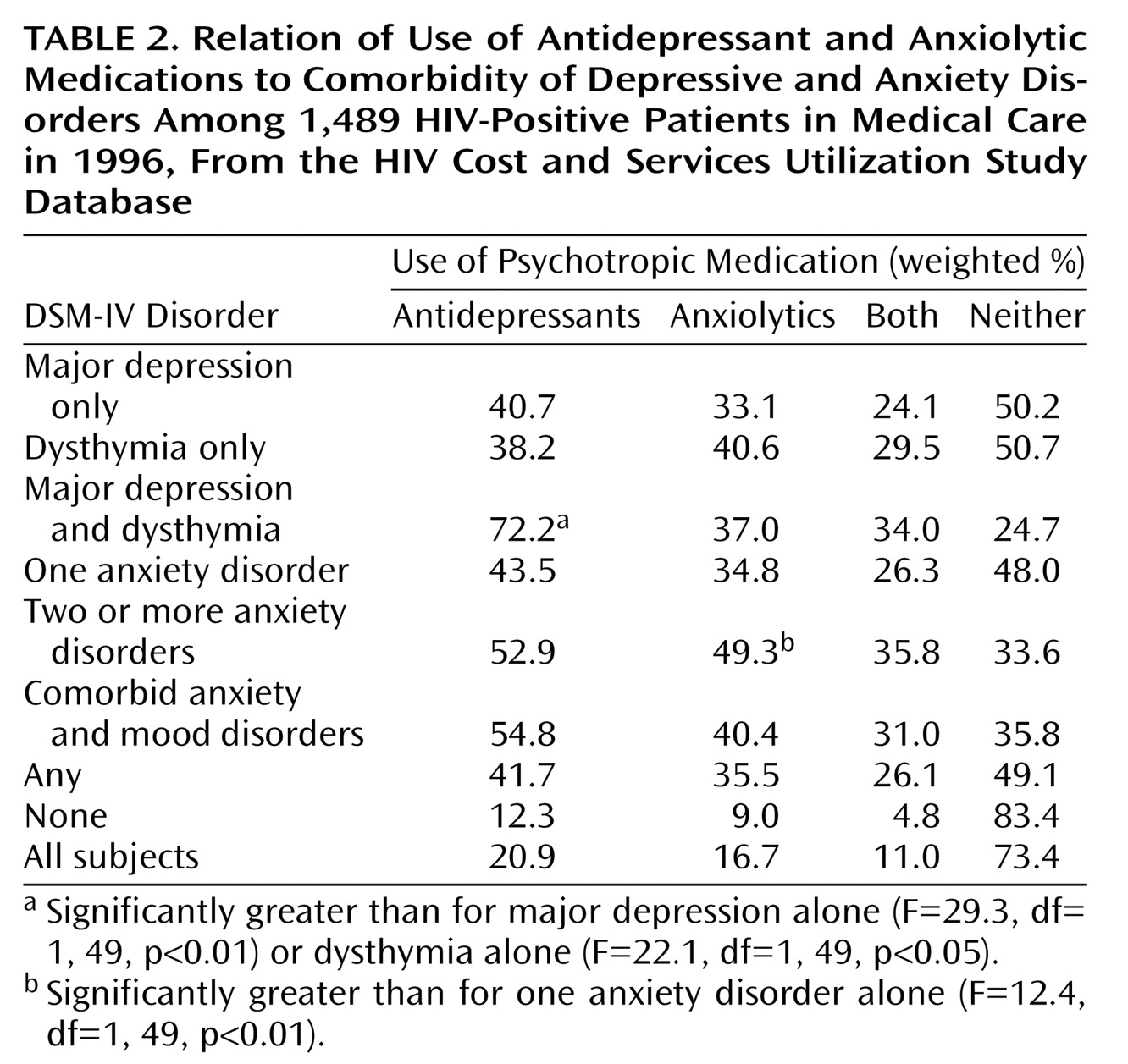

Use of antidepressants and anxiolytics tended to increase in the presence of comorbidity (

Table 2). Thus, patients with both major depression and dysthymia were more likely to have taken antidepressants (72.2% of cases) than patients with only major depression or dysthymia (40.7% and 38.2%, respectively). Among patients with anxiety disorders, the presence of more than one anxiety disorder increased the rate of use of anxiolytics but not of antidepressants.

Number and Type of Medications

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were the most commonly used antidepressants among patients with any mental disorder (25.7%), followed by tricyclics (16.1%). Among patients with mood disorders, the rate of use of SSRIs (28.8%) was twice that of tricyclics (14.8%).

Benzodiazepines accounted for 66.3% of all anxiolytics. Of the patients with any mental disorder, 23.4% reported use of benzodiazepines. Alprazolam was the most commonly used benzodiazepine (10.9% of patients with any mental disorder), followed by diazepam (7.2%). Use of benzodiazepines was also reported by 5.6% of the patients who screened negative for mental disorders (2.4% took alprazolam, and 1.8% took diazepam).

Among patients taking psychotropics, the mean number of medications taken during the last 6 months was 2.8 (SD=2.0, range=1–24). Of the patients taking antidepressants, 63.0% also took at least one other type of psychotropic. Of the patients taking anxiolytics, 73.1% also took at least one other type of psychotropic.

Psychotropics and Antiretrovirals

Use of highly active antiretroviral therapy was reported by 61.9% of the patients. Of the patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy, 22.2% took an antidepressant (12.8% took an SSRI, and 9.3% took a tricyclic), 17.6% took an anxiolytic (11.0% took a benzodiazepine), 5.0% took an antipsychotic, and 3.0% took a psychostimulant. These rates are similar to those found among the patients not receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy, of whom 18.8% took an antidepressant (11.9% took an SSRI, and 5.2% took a tricyclic), 15.1% took an anxiolytic (10.4% took a benzodiazepine), 4.2% took an antipsychotic, and 3.0% took a psychostimulant.

Severity of HIV and Use of Psychotropics

No statistically significant differences in use of psychotropic drugs were found among the patients with asymptomatic HIV infection, symptomatic HIV infection, or AIDS.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

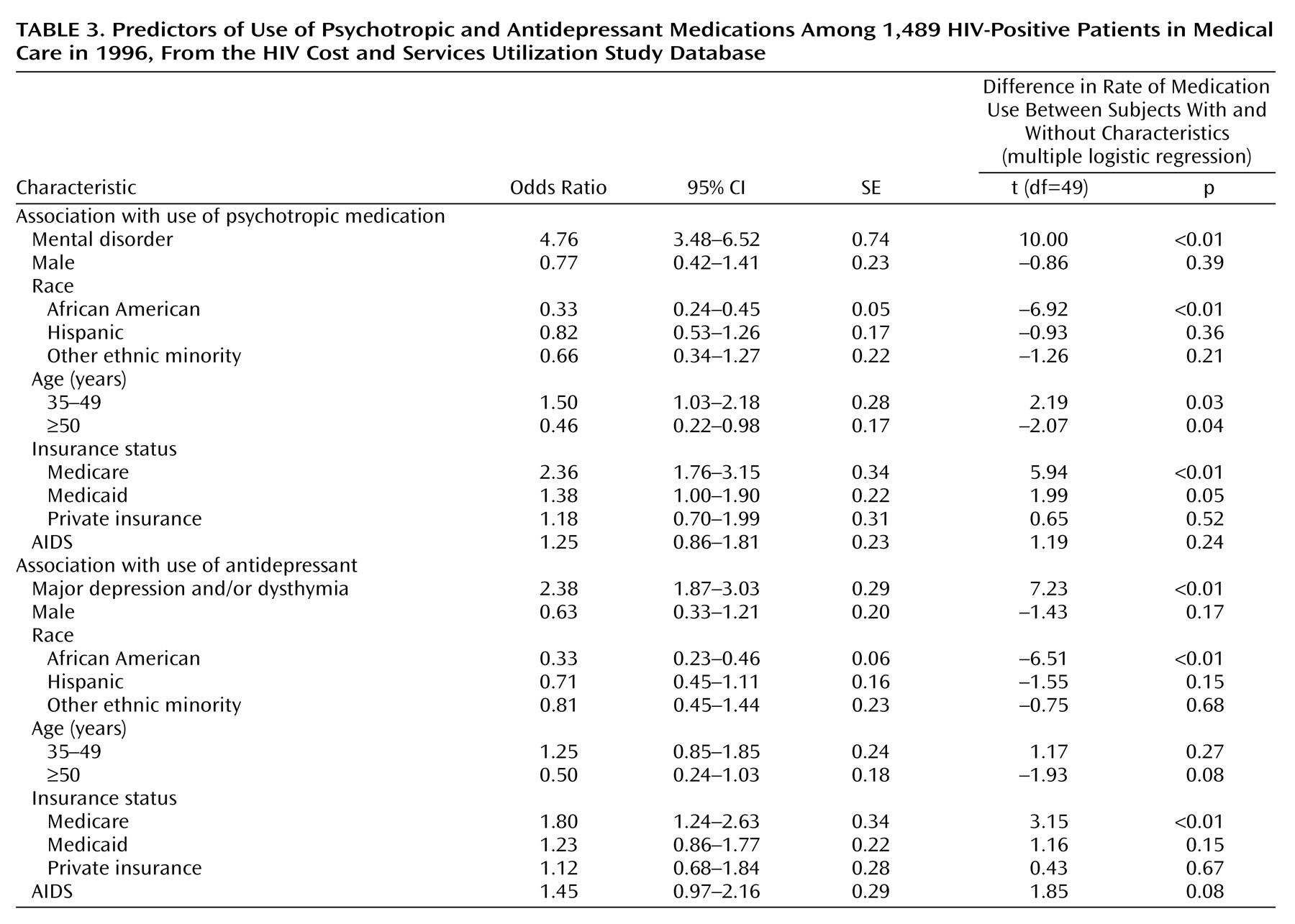

Use of psychotropic medications was greater among individuals with a mental disorder (odds ratio=4.76, 95% CI=3.48–6.52) or Medicare insurance coverage (odds ratio=2.36, 95% CI=1.76–3.15) or age 34–49 years (odds ratio=1.50, 95% CI=1.03–2.18) than among individuals without these characteristics (

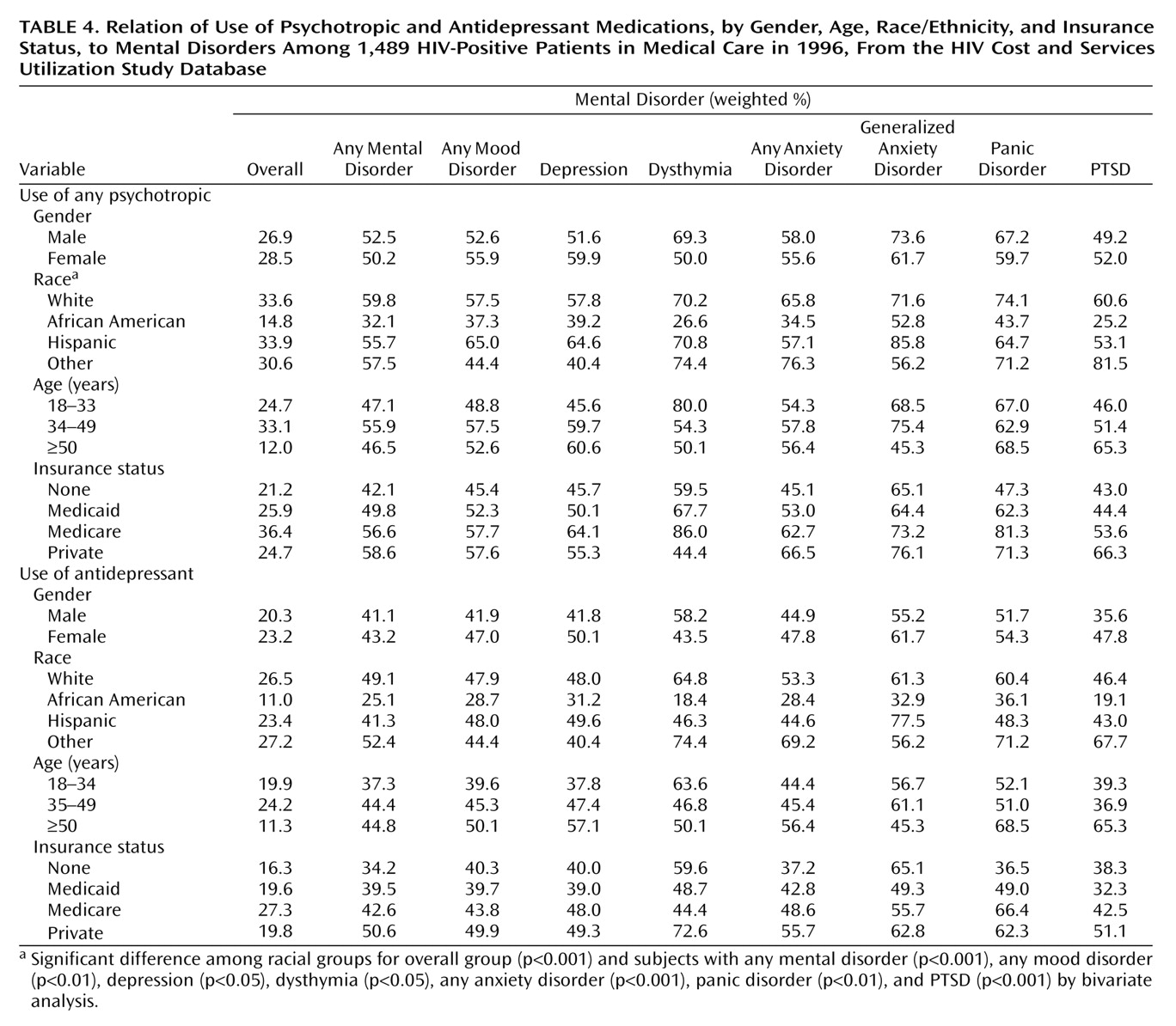

Table 3). No gender differences were found: 26.9% of men and 28.5% of women took psychotropic medications (

Table 4). Use of psychotropic drugs was lower among individuals who identified themselves as African American (odds ratio=0.33, 95% CI=0.24–0.45) or were 50 years or older (odds ratio=0.46, 95% CI=0.22–0.98) (

Table 3). No age differences were apparent, however, when patients with mental disorder only were considered (

Table 4). Among patients with any mental disorder, the estimated rate of use of psychotropics was 59.8% for whites, 32.1% for African Americans, and 55.7% for Hispanics (

Table 4).

Use of antidepressant medications was positively associated with the presence of a mood disorder (odds ratio=2.38, 95% CI=1.42–3.55) and Medicare insurance coverage (odds ratio=1.80, 95% CI=1.23–2.85) and negatively associated with self-identification as African American (odds ratio=0.33, 95% CI=0.23–0.45), compared to individuals without these characteristics (

Table 3). Among patients with mood disorders (i.e., major depression and/or dysthymia), the rate of use of antidepressants was 47.9% among whites, 28.7% among African Americans, and 48.0% among Hispanics (

Table 4).

Among the patients with mood disorders who did not receive antidepressant medication, the estimated use of psychosocial interventions (individual, group therapy, or a support group) was 25.2% for whites, 31.9% for African Americans, and 35.5% for Hispanics. Thus, overall, 61.0% of whites, 51.4% of African Americans, and 66.7% of Hispanics with mood disorders reported using antidepressant medications or some type of psychosocial intervention.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first national probability study to examine the use of different types of psychotropic medications by HIV-positive patients. The results indicate that 27.2% of HIV-positive patients who received medical care in 1996 were treated with psychotropic medications in the 6 months before the study interview. This rate is consistent with that obtained through the baseline assessment of mental health services in the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study sample

(11), which was conducted 6 months before the survey of psychotropic use here reported. Antidepressants were the most commonly used psychotropic, followed by anxiolytics and, much less frequently, antipsychotics and psychostimulants. Among antidepressants, SSRIs were more commonly used than tricyclics. Most patients taking psychotropics took more than one class of medication. Comorbidity of mental disorders was associated with greater drug use. These results are generally consistent with previous reports regarding psychotropic prescribing patterns among patients in primary care and psychiatric practice settings

(21,

22).

The estimated rates of mental health disorders during the 6 months before the interview are lower than the 12-month prevalence rate previously reported for the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study sample

(3). Several factors may have accounted for these lower rates, such as the shorter time frame (6 months), use of the long form of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, which may be more specific than the short form used by Bing et al.

(2,

23), and the repeated interviewing of the same patients with consequent possible regression to the mean and diagnostic attenuation.

We found that 43.9% of the HIV-positive patients with a DSM-IV diagnosis of major depression supported by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview took antidepressant medication. This rate is somewhat higher than expected on the basis of previous reports that only one-half of the primary care patients with major depression are accurately diagnosed

(5,

22) and only one-half of those diagnosed are actually treated with antidepressants

(24,

25). Some of these studies, however, were conducted in the mid-1980s, and there are indications that the rate of treatment of depression markedly increased in the 1990s

(26). HIV-positive patients may be also more likely to be treated for psychiatric disorders, perhaps because of the extensive medical contacts related to HIV infection. More than one-half of the patients with a diagnosis of major depression under care for HIV infection reported not having been treated with antidepressants. How much this finding may be due to failure to recognize depression, failure to treat a diagnosed disorder, concern about polypharmacy and drug interactions in this population, or a preference for nonpharmacological interventions cannot be fully disentangled based on these data. On the basis of previous reports

(5,

22), failure to recognize the disorder is rather common. However, a recent report that only about one-third of patients seeking treatment for mood or anxiety disorders may receive appropriate care

(13) suggests that other causes besides failure to diagnose contribute to undertreatment. There are also indications that most primary care patients with depression prefer psychotherapy over medications

(27). In our study, the rate of use of psychotherapy among depressed patients not receiving antidepressant medication was 25.2% for whites, 31.9% for African Americans, and 35.5% for Hispanics. The survey used a broad definition of “psychotherapy,” encompassing any contact with a mental health provider for individual or group therapy (including family and marriage counseling) and attendance at support group meetings. Even after an accounting for use of these psychosocial interventions, it appears that at least one-third of all patients with a mood disorder did not receive treatment.

Antidepressants are effective for both depressive and anxiety disorders, and this can explain the high use of these drugs by patients with anxiety disorders (

Table 2). An estimated 12.3% of the patients with no mental disorder, based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, received antidepressant medication (

Table 1). Given that 29.1% of all of the patients had a mental disorder and only 41.7% of them received antidepressants, it can be inferred that a sizable amount (41.8%) of all antidepressant use was by patients who did not have a diagnosis of a mental disorder according to the long-form Composite International Diagnostic Interview during the last 6 months. It is possible that a mental disorder had been previously present and that the medication was used to prevent recurrence

(28). However, the average duration of antidepressant treatment is less than 3 months, and most patients discontinue medication within 6 weeks of starting treatment

(28–

30). Antidepressants could have been prescribed to treat subsyndromal forms of depression or anxiety

(31) or to manage chronic pain

(32). The study interview inquired about “medications for personal or emotional problems, such as emotions, nerves, alcohol, drugs, or mental health,” but the relationship between pain and depression is complex, and the two conditions can overlap

(33). Likewise, anxiolytics are often used for managing insomnia, a common symptom in HIV-positive patients

(34).

Use of multiple psychotropics was common. Although it cannot be ruled out that some medications were taken sequentially during the 6-month period, concomitant use was probably high. As expected, the concomitant use of antiretroviral and psychotropic medications was also common, with more than one-fifth of the patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy also taking an antidepressant. The study of the possible pharmacological interactions between antiretroviral and psychotropic medications has high clinical relevance

(35). For instance, protease inhibitors can inhibit several cytochrome P-450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of psychotropics

(36), resulting in a higher plasma concentration of these drugs

(37).

After control for mental disorder, gender, age, insurance status, and presence of AIDS, African American patients were significantly less likely to have received psychotropic medications, and antidepressants in particular, than whites and Hispanics (

Table 3 and

Table 4). This finding is consistent with previous reports of less use of health care services for HIV infection by African Americans

(15) and for mood and anxiety disorders in the general population

(13,

38). This lower use of psychotropics by African Americans may be partly compensated by a higher reliance on psychosocial interventions. This is consistent with a recent survey showing that African Americans in primary care suffering from depression were twice as likely as white patients to prefer psychotherapeutic intervention than antidepressant medication

(27). Unexpectedly, Hispanic ethnicity was not associated with lower use of psychotropics or antidepressants in this study. A national survey in the general population (i.e., not focused on HIV-positive patients) reported a greater unmet need of mental health services among Hispanics than among whites

(14). Another study, however, found that, in the early and mid-1990s, the pharmacological treatment of depression dramatically increased among Hispanic patients but remained low among African Americans

(39).

Contrary to our prediction, female sex was not associated with higher use of psychotropics in general or antidepressants in particular. Previous studies have reported that about two-thirds of psychotropic medication visits are for women, both in primary care and psychiatric settings. The present findings may reflect characteristics of HIV-positive men as being more likely to search for pharmacological treatment of mood and anxiety disorders than HIV-negative men. A less marked—but still significant—effect of age was also detected, with middle-age patients being more likely than older patients to have been treated with psychotropics (

Table 3). This effect, however, was present only in the entire sample and disappeared when patients with a mental disorder only were analyzed (

Table 4).

As expected, Medicare patients have a higher rate of psychotropic use (

Table 3). Patients with Medicaid or without insurance, however, had rates of use that were comparable to those of patients with private insurance, thus indicating that for patients already in medical care these differences in insurance status do not significantly affect the use of psychotropics.

In addition to the study limitations mentioned, a few others also need to be pointed out. The severity of psychopathology was not assessed, and this limits inferences on the adequacy of treatment. For instance, undertreatment of severe depression would be of greater concern than undertreatment of milder forms. Also, chart diagnoses made by the patients’ providers were not obtained. Information about the prescribers of psychotropic medications (e.g., family doctor, psychiatrist), duration of treatment, and dose were not available.

In conclusion, this study of a national probability sample of HIV-positive patients found that psychotropic medications, and antidepressants and anxiolytics in particular, were commonly used by HIV-positive patients receiving medical care in the United States. However, more than one-half of the patients suffering from major depression were not treated with antidepressants, even though a substantial portion of those not receiving medication reported use of some type of psychosocial intervention. African Americans were less likely to have been treated with psychotropic medications, thus adding to other data indicating differences in health care among ethnic groups.