Nearly a century ago, Hoch

(1) proposed a relationship between a withdrawn, detached personality type and the development of schizophrenia. This dimension of personality was conceptualized as “schizoidea” or schizoid personality by Bleuler

(2), Kraepelin

(3) and Kretschmer

(4). Schizoid temperament, according to Kretschmer, existed on a continuum ranging from being cold and insensitive to being “nervously sensitive.” Expanding beyond these conceptualizations of schizoid traits, Meehl

(5) posited a model of personality organization reflecting the latent liability to schizophrenia, namely schizotypy, that included the four fundamental symptoms of cognitive slippage, interpersonal aversiveness, anhedonia, and ambivalence. Subsequently, a genetic basis for both schizotypal personality and schizophrenia was proposed

(6–

9), and the neurodevelopmental hypothesis took the center stage in explaining what came to be known as the spectrum concept of schizophrenia

(7). Over the years, this spectrum has been variously defined. The broadest definition included, besides other entities, all the three cluster A personality disorders (schizoid, paranoid, and schizotypal), and the narrowest definition was restricted to schizotypal personality disorder

(10).

Discussion

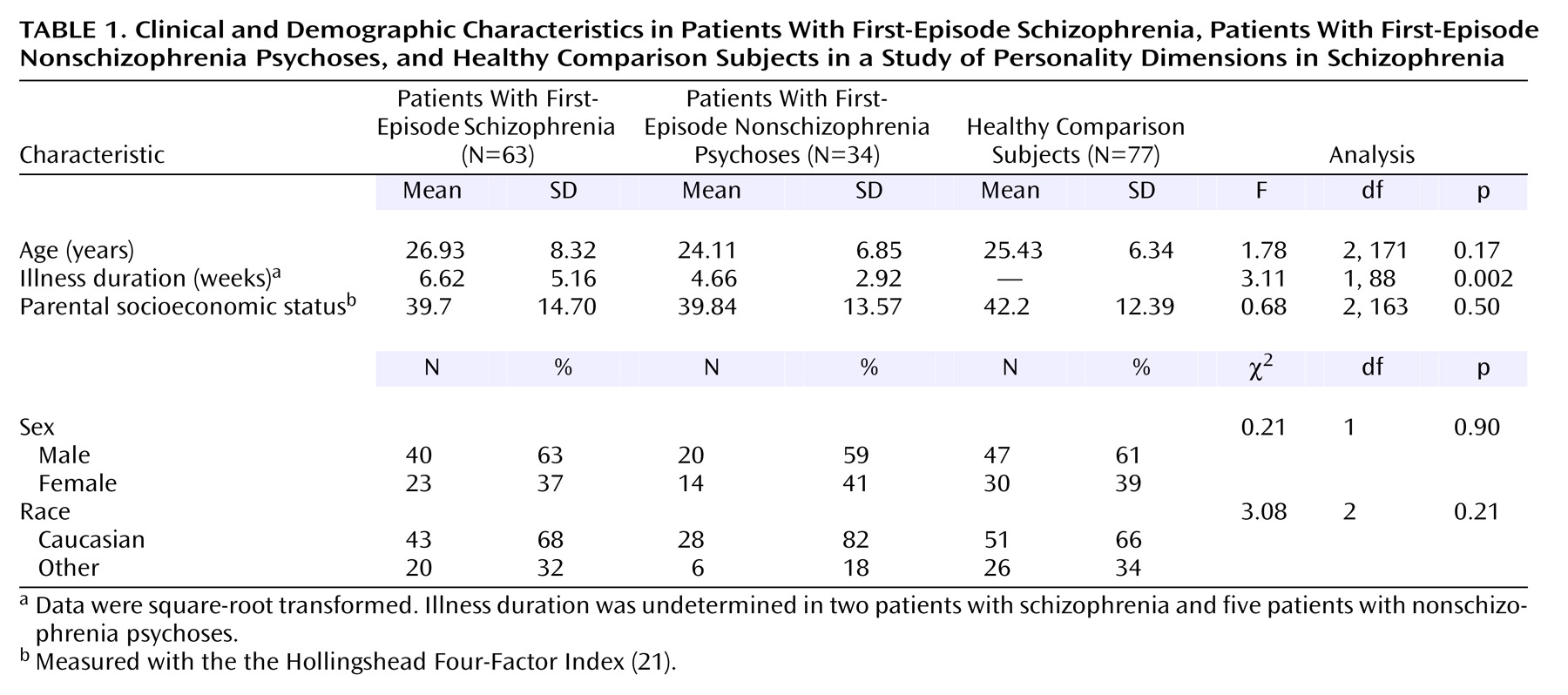

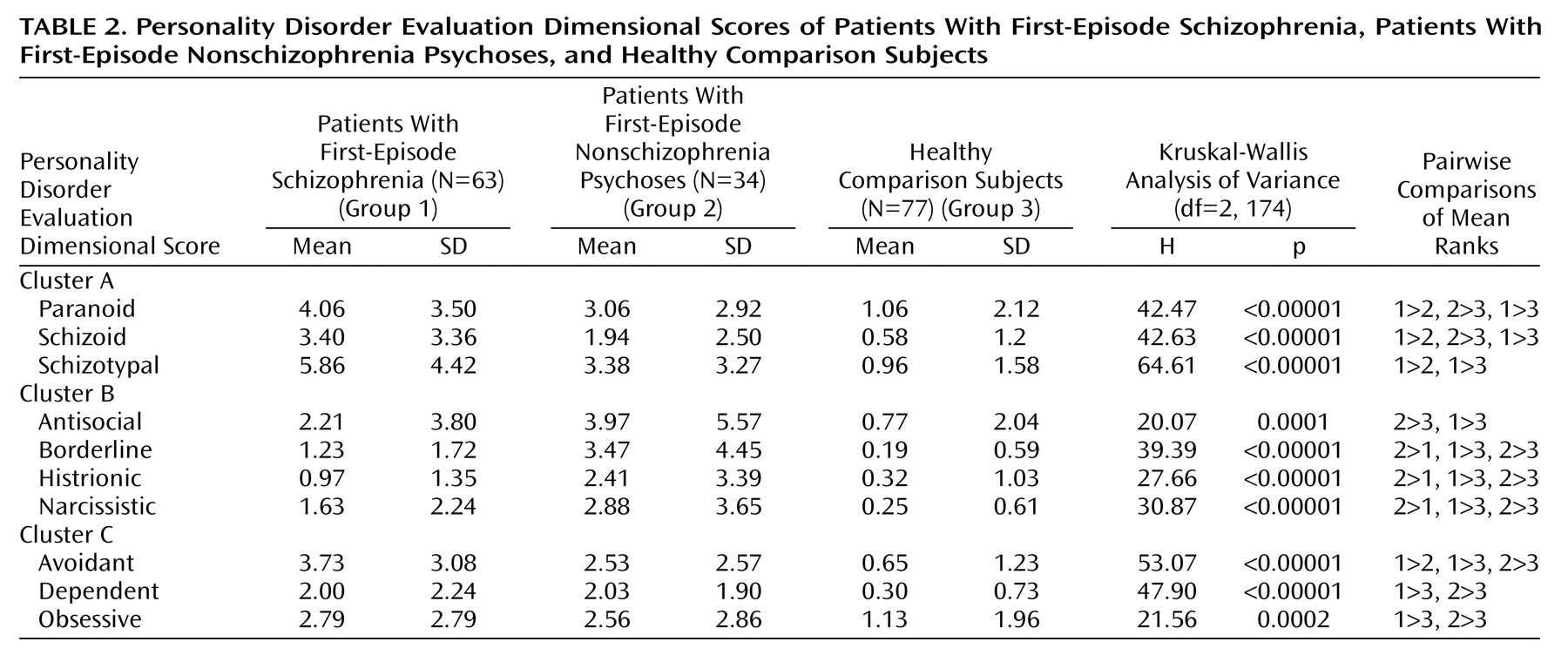

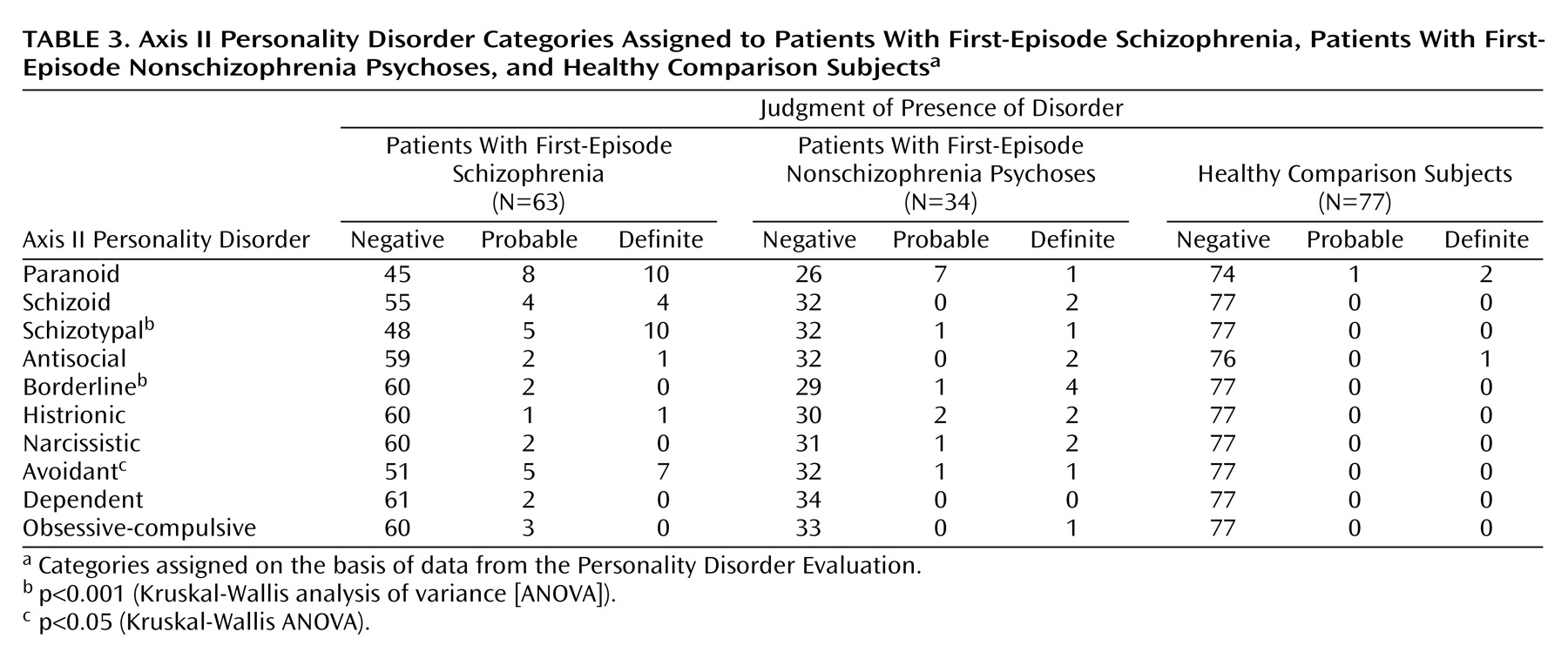

The main findings of our study include the predicted higher level of cluster A characteristics among the first-episode schizophrenia patients and the predicted higher level of cluster B characteristics in the patients with first-episode nonschizophrenia psychoses. These findings are similar to those of earlier studies

(14,

24–26). Our observations provide some validation of the current approach to classifying personality disorders. Of particular clinical interest was the higher level of cluster C personality disorder characteristics in schizophrenia patients. In concert with previous developments in this area of research

(13), the main focus of our discussion is on personality disorders in first-episode/recent-onset schizophrenia and the association of cluster C personality disorders with schizophrenia.

Although previous studies have examined personality dimensions in first-episode schizophrenia, to our knowledge our study is the first study to examine these traits in patients with psychotic disorders in comparison with healthy comparison subjects. It is difficult to compare our results with those of the few other studies that have carried out structured assessment of personality disorders in first-episode/recent-onset schizophrenia, primarily because of differences in illness characteristics (duration of illness, medication status), methods of collecting the data (patient versus informant interviews), dimensional and categorical approaches to personality, and the instruments used for assessing the personality domains. Cuesta el al.

(27) recently reported on personality dimensions in first-episode psychosis but used different tools to assess both personality dimensions and psychopathology. Hogg et al.

(28) showed that schizotypal, antisocial, and borderline personality disorders were the most common personality disorders in schizophrenia on the basis of informant interviews with the Structured Interview for DSM-III Personality Disorders but that dependent, narcissistic, and avoidant personality disorders were the most common personality disorders on the basis of data from a self-report inventory. However, the authors found little agreement between the two instruments. Another study that used the Structured Interview for DSM-III Personality Disorders reported an association of schizotypal and antisocial personality disorders with schizophrenia

(29). One limitation of these previous studies was that the investigators were not blind to the main psychiatric diagnosis and/or to clinical information about the patients. This limitation assumes importance in light of the finding of Bernstein et al.

(30) that the prevalence of cluster A personality disorders was significantly lower when the rater was blind to patients’ clinical information than when the rater was not. A study from the United Kingdom that used a semistructured interview to rate premorbid personality according to ICD-9 classifications demonstrated that premorbid schizoid, paranoid, and explosive traits were more common in patients with schizophrenia than in patients with other nonorganic psychoses

(14). However, the instrument used did not cover all items included in the DSM-III/DSM-III-R conceptualization of personality disorders. Using a structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R personality disorders, Solano and DeChavez

(13) showed that the most common personality disorders in patients with schizophrenia, in order of frequency, were avoidant, schizoid, paranoid, dependent, and schizotypal personality disorders. They also showed that almost 50% of the 40 schizophrenia patients in their study had two or more personality disorders. In addition, avoidant personality disorder significantly correlated with schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders, as shown by our study. One limitation of this study was the lack of comparison with patients with nonschizophrenia psychoses or with healthy subjects.

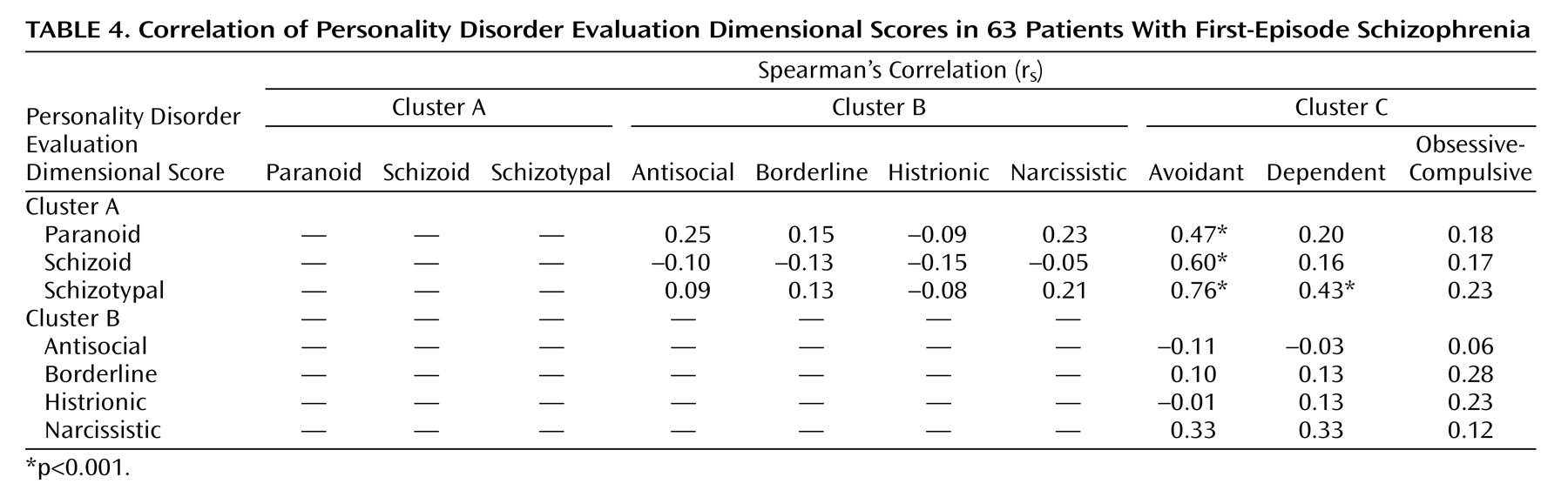

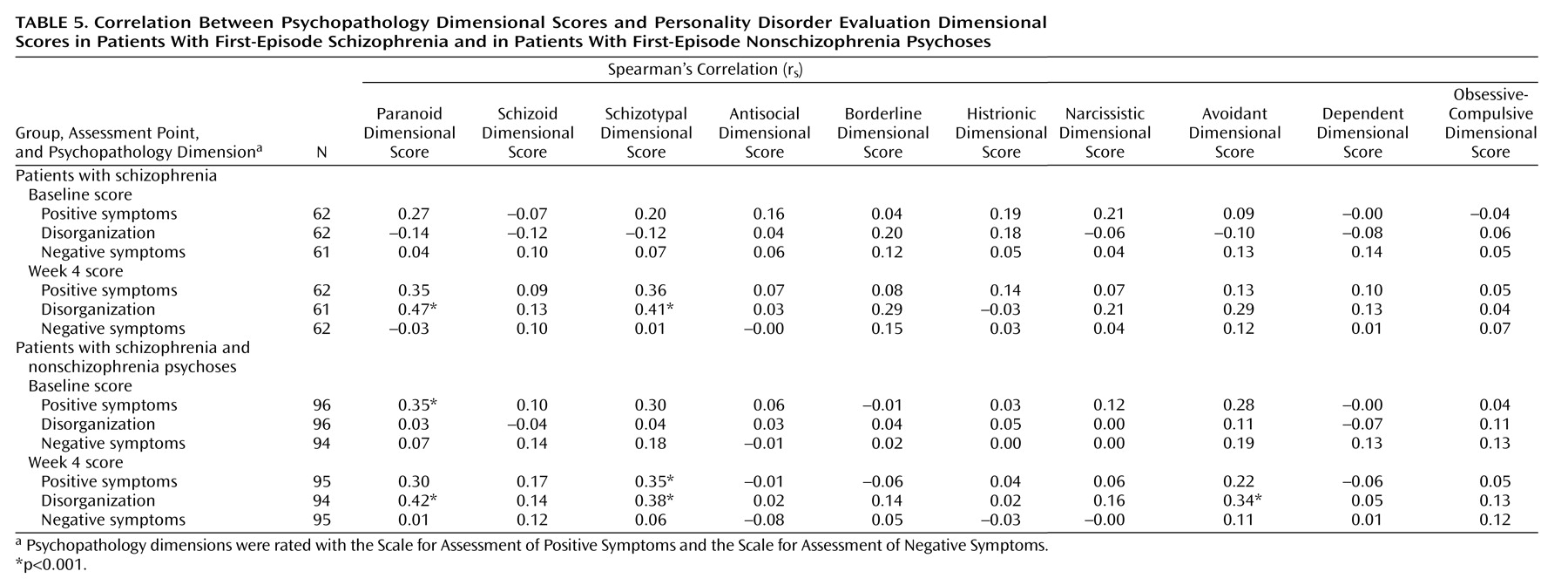

Another finding of our study was the correlation between paranoid, schizotypal, and avoidant personality dimensions and the disorganization dimension of psychosis 4 weeks after intake. Thought disorder, which is a part of the disorganization dimension, has been proposed as a marker of familial vulnerability to schizophrenia (a trait marker)

(31), and thus it may have persisted after the stabilization of acute psychotic symptoms. The correlation between cluster C personality dimensions and the disorganization dimension of psychosis has been shown in a previous study

(32). This study showed that passive-dependent personality dimensions (which have some similarity to cluster C traits) were associated with the disorganization dimension of psychosis. However, our finding of a lack of correlation between personality dimensions and negative symptoms differs from that of a previous study of personality dimensions in first-episode psychosis, in which higher scores on the schizoid dimension were related to more severe negative symptoms

(27). This difference may be due to difference in the scales used to assess psychopathology, as the disorganization dimension is better represented by the SAPS and SANS than by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, which was used in the previous study

(27,

33).

In light of the literature on personality disorders in schizophrenia, the finding of a higher frequency of nonspectrum personality disorders in schizophrenia raises some interesting questions. First, is there a theoretical basis for the occurrence of nonspectrum personality disorders in schizophrenia? Second, can the neurodevelopmental hypothesis, which has traditionally supported schizophrenia as an extension of schizoid or schizotypal personality disorders

(7,

32), explain the occurrence of nonspectrum personality disorders in this disorder? Addressing the first issue, we take a brief look at the historical concept of schizoid personality disorder. Kretschmer’s conceptualization of schizoid temperament consisted of two variants: the hyperaesthetic type and the anesthetic type characterized by hypersensitivity and insensitivity in social context, respectively

(4). These categories have some similarities with the present-day avoidant and schizoid personality disorders. Kretschmer also reported combinations of these variants and transition from one to another. This relationship between some cluster A and cluster C personality types also existed before DSM-III, as the conceptualization of schizoid personality disorder then included features of what are now known as schizotypal and avoidant personality disorders. Later, the core feature promulgated to differentiate schizoid personality disorder from avoidant personality disorder was the extent to which the individual desired social contact versus the extent to which the individual was indifferent to social contact. However, this trait is considered by some authors to exist on a continuum

(34), which is consistent with our and others’ observations of an association between these two personality disorders

(13,

35,

36). This association between cluster A and cluster C personality disorders is further bolstered by a factor analytic study of personality traits in which the DSM-III-R-defined schizoid, schizotypal, and avoidant personality disorders were found to be represented by a single common factor—social avoidance

(37). Together, these findings suggest that nonspectrum personality disorders, especially cluster C avoidant personality disorder, may be an important axis-II comorbidity in schizophrenia-like psychosis. This comorbidity may occur because of similarities between the symptoms of cluster A personality disorders and those of avoidant personality disorder. However, if similarity were the sole explanation of the comorbidity, we would have expected the strongest correlation between the schizoid personality and avoidant personality dimensions, as these two differ mainly in the aspect of desire (or lack of desire) to have social contact. The strong correlation between the dimensions of schizotypal personality, which is regarded as the core spectrum personality type associated with schizophrenia, and the avoidant personality dimensions may indicate that the latter possesses trait-like characteristics similar to the traditional spectrum personality disorders. Deciphering this relationship would require more elaborate studies involving relatives of patients with schizophrenia and high-risk populations.

A theoretical framework for the occurrence of nonspectrum personality disorders in schizophrenia is better understood by the dimensional concept of schizotypy, wherein positive schizotypy represents the psychosis-like traits, while negative schizotypy represents the schizoid-avoidant traits

(38). This relationship is also supported by the finding from the Roscommon Family study that avoidant symptoms were the only factor in schizotypy to distinguish relatives of probands with schizophrenia from relatives of probands with psychotic affective illness

(35). Meehl’s conceptualization of schizotypy

(5) includes the symptom of “social aversiveness,” characterized by social fear, expectation of rejection, and conviction of one’s unlovability, which is reminiscent of the present-day conceptualization of avoidant and dependent personality disorders. An alternative explanation of cluster C comorbidity in schizophrenia is one of etiological heterogeneity in schizophrenia, with the “nongenetic” type preceded by a normal premorbid personality or associated with nonspectrum personality disorders and the “genetic” type preceded by spectrum personality disorders

(13,

39). However, to date, the search for such etiological subtypes of schizophrenia has not been fruitful

(10,

40).

Literature on the interaction between the contemporary psychosocial and neurobiological models of the pathogenesis of schizophrenia suggest neurodevelopmental insults to brain regions responsible for social cognition, including the basal ganglia, amygdala, and orbitofrontal cortex

(41). The concept of social cognition includes dimensions of attachment, social anxiety, sensitivity, and social avoidance, which represent the very domains affected in avoidant and dependent personality disorders

(37). Thus, there exists some evidence to support a neurodevelopmental basis for the occurrence of some cluster C personality disorders in schizophrenia. A hypothetical mechanism could be that the neurodevelopmentally induced cognitive deficits related to social tasks may overwhelm a vulnerable individual when the latter meets the demands of “secondary socialization”

(42), which occurs during adolescence and early adulthood, the typical age for the shaping of adult personality and also for the onset of schizophrenia. This interpretation is supported by the association of certain personality domains with poor performance on cognitive tasks. For instance, patients with psychosis who have passive-dependent traits have been shown to have poorer cognitive performance on memory tasks

(43). Another study showed that first-degree relatives of schizophrenia patients who scored high on the disorganization dimension of schizotypy had more incorrect responses on a continuous performance test

(44). This cognitive deficit occurs because of failure to suppress the incorrect responses, a feature of orbitofrontal dysfunction, which is also implicated in impaired social cognition in schizophrenia

(41,

44). Taken together, these findings suggest that the putative association of cognitive dysfunction and personality dimensions favors a neurobiological basis of personality-cognitive impairment in psychosis, as hypothesized by some authors

(43). Because our study had a cross-sectional design, we cannot speculate about whether personality dimensions have a pathogenetic influence on the development of psychosis, although compelling evidence gleaned from longitudinal studies, studies of high-risk populations, and family studies suggests that personality dimensions may be a predisposing factor for psychosis (see references

30 and

32). Other competing models pertaining to the relationship between personality and psychosis include personality disorder as an attenuated form of psychotic disorder, the pathoplastic effects of personality on psychopathology, and personality disorder as a complication of a psychotic disorder. Several authors have discussed these models at length

(27,

45).

Although this discussion has mainly focused on cluster C personality disorders in schizophrenia, some investigators have found associations involving other personality disorders, particularly an association between antisocial personality disorder/sociopathic traits and schizophrenia

(20,

28,

29). Our observations are also consistent with these findings. We observed higher levels of the cluster B dimensions in the schizophrenia group, compared to the healthy subjects, but the patients with nonschizophrenia psychoses had significantly higher scores in all the cluster B dimensions except antisocial personality, compared to the schizophrenia patients. The differential association of cluster A dimensions with schizophrenia-like psychosis and of cluster B dimensions with affective psychosis may partly be explained by commonalities in the neurobiology of these conditions. For example, increased dopaminergic function in schizotypal personality disorder has been related to psychosis-like symptoms in this personality disorder, and abnormalities in the serotonergic system have been found in individuals with borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder

(46). More studies are needed to decipher any neurobiological similarities between cluster C personality types and schizophrenia.

The strengths of our study consist of the inclusion of a relatively large, well-characterized group of first-episode schizophrenia patients, the inclusion of both a group of patients with first-episode nonschizophrenia psychoses and a healthy comparison group, and the use of a standard approach to personality assessments by a rater who was blind to diagnostic categorization. This study also has some potential limitations. First, it is difficult to be certain that the clinician who administered the Personality Disorder Evaluation was completely blind to the diagnostic group of the interviewee. However, personality evaluations were typically conducted before the consensus diagnostic meetings. Second, although the condition of many patients had stabilized, some continued to have psychotic symptoms, which raises the question of whether the Personality Disorder Evaluation ratings were “colored” by concomitant symptoms of an axis I disorder. To overcome this potential problem of confounding “trait” and “state,” Personality Disorder Evaluation dimensions were correlated with psychopathology assessed at baseline and also at 4 weeks, when we expected the acute psychotic symptoms to start remitting. A better strategy to separate the influence of axis I disorders on the presentation of axis II symptoms, however, is to prospectively study subjects with high risk for schizophrenia. However, besides being time consuming and laborious, such a strategy may not result in the full distinction of prodromal symptoms from premorbid personality traits, because symptoms of the schizophrenia prodrome overlap with those of schizotypal personality disorder

(47). Third, the possibility of biased retrospective recall and the lack of corroborative information from subjects’ relatives, as highlighted in previous studies of personality disorders

(30,

45,

48), is also relevant to this study. Fourth, we did not have the data to ascertain the duration of personality traits experienced by the subjects, and none of the existing personality inventories allows quantification of the individual traits. In future studies, such data should be carefully collected from patients early in the course of psychotic disorders. Finally, the observed association of cluster B traits in nonschizophrenia psychoses needs to be interpreted with caution because of the comparatively small number of subjects and heterogeneity of the group.

In conclusion, this study confirms and extends the previously reported association of nonspectrum personality disorders with schizophrenia and attempts to explore the theoretical and pathophysiological bases for the correlation between nonspectrum personality disorders and the traditional schizophrenia spectrum personality disorders. More systematic research is required to replicate these findings and to further elucidate the relationship of some cluster C personality disorders with psychopathology, cognitive functioning, and outcome in schizophrenia.