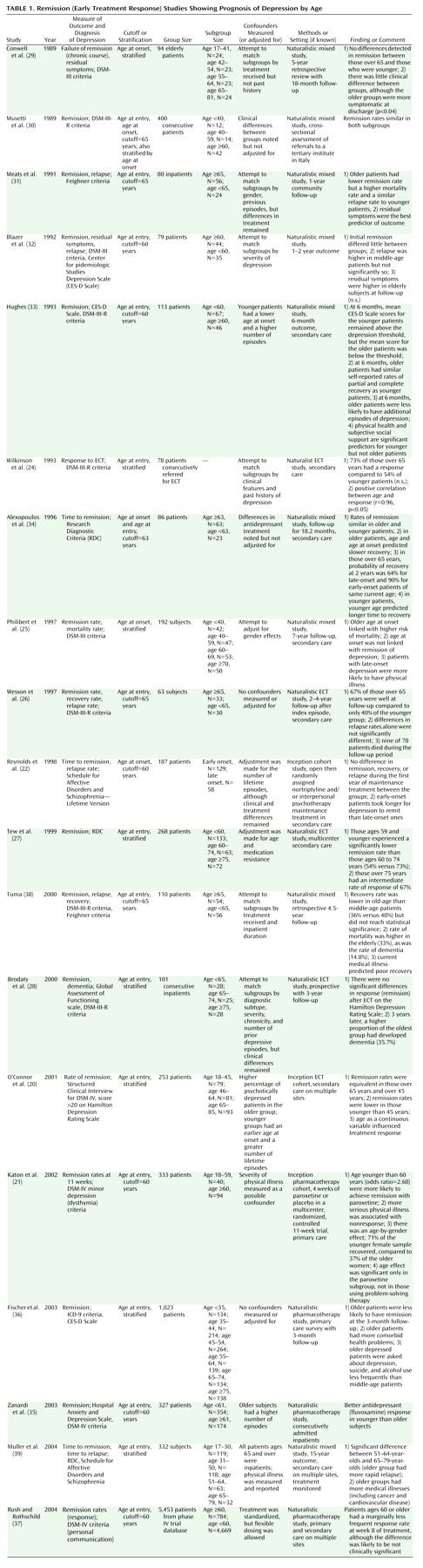

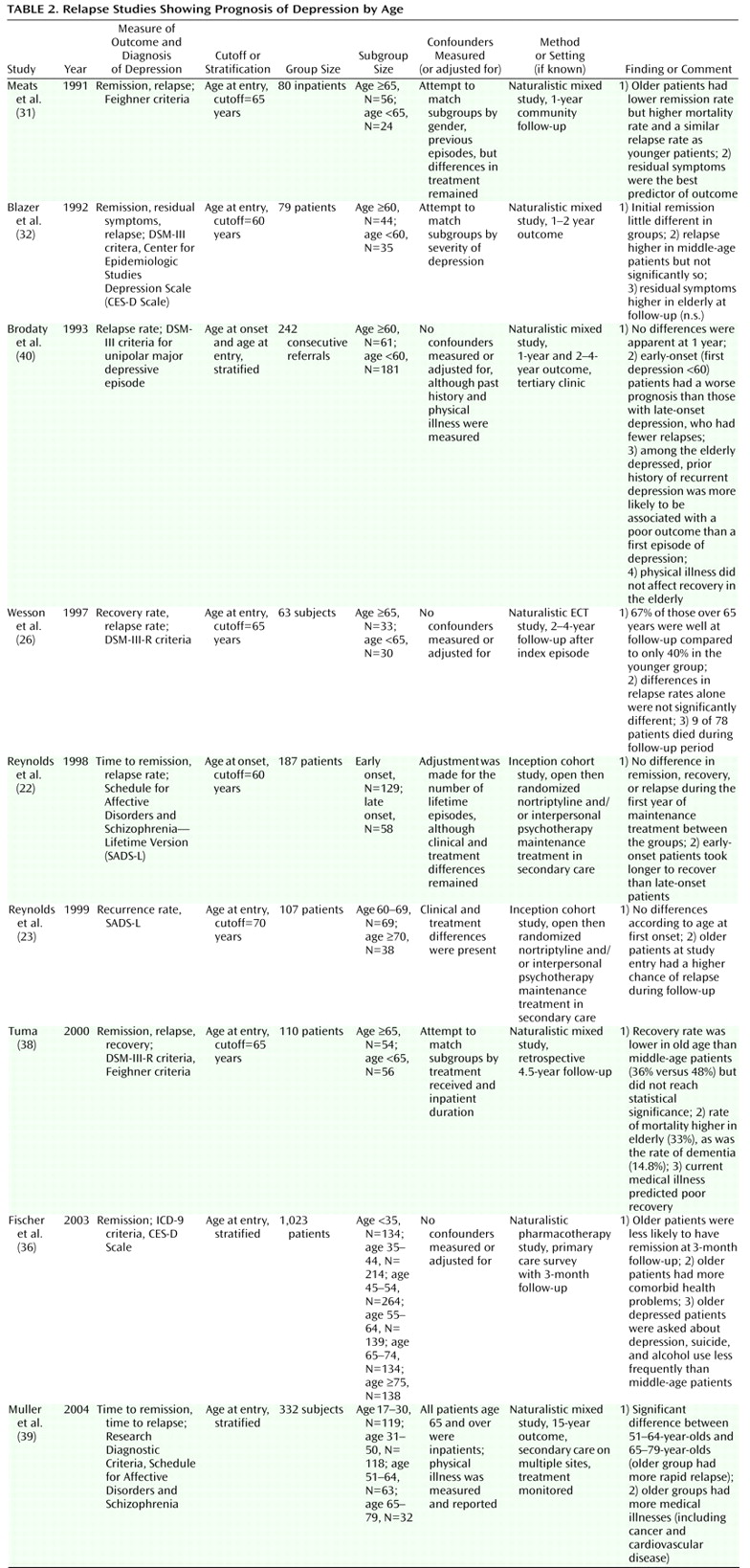

The evidence regarding treatment response in relation to age is less consistent. Two large studies have shown that older patients at the time of pharmacological treatment for depression have an inferior treatment response than middle-age patients

(35,

36), but a number of other reports have shown the opposite finding

(20,

31,

33) or no statistical difference

(25,

30,

32,

34). Together this suggests that rates of response are not substantially different between groups, a hypothesis supported by the largest study to date, which showed only a tiny difference in response rates, which is unlikely to be of clinical significance

(37). The results from naturalistic ECT surveys (all of which have used age at treatment as the predictor variable) have suggested small or absent differences in treatment response, but interpretation is more difficult because of methodological limitations of relatively small sample sizes and selection bias in the use of ECT itself. Furthermore, although it is possible that the prognostic effect of age may differ according to the type of treatment used, only one study to date, to our knowledge, has hinted at differential effects

(21).

Regarding studies of elderly depressed patients stratified by age at first-episode onset, it has been reported that patients with a late onset of first-episode depression have a better treatment response

(22) and a lower chance of subsequent relapse

(40) or, in contrast, an inferior treatment response

(29,

34). These discrepant results may be understood by the effect of two confounding factors working in opposite directions. Elderly patients of the same chronological age but an earlier age at onset than a group with a later age at onset, by definition, have a longer illness duration and a higher probability of a greater number of previous episodes, which is one of the strongest predictors of relapse and recurrence

(67). However, medical comorbidity is more likely in people with late-onset depression without a past psychiatric history

(47,

48). Evidence from comorbidity studies has demonstrated that time to remission may be longer and rates of remission may be lower when medical comorbidity is present. Thus, a first onset of depression in late life

without comorbidity may have a preferentially good outcome, but more commonly, a first onset of depression in late life is associated with a higher rate of medical comorbidity than in early-onset patients. Hence, a first episode in late life (with comorbidity) most commonly has a worse prognosis. Therefore, the influence of chronological age and age at onset on prognosis is closely linked with past psychiatric history, as well as current and future comorbidity. Comorbid medical illness (and dementia) is an important reason why patients do worse with increasing age

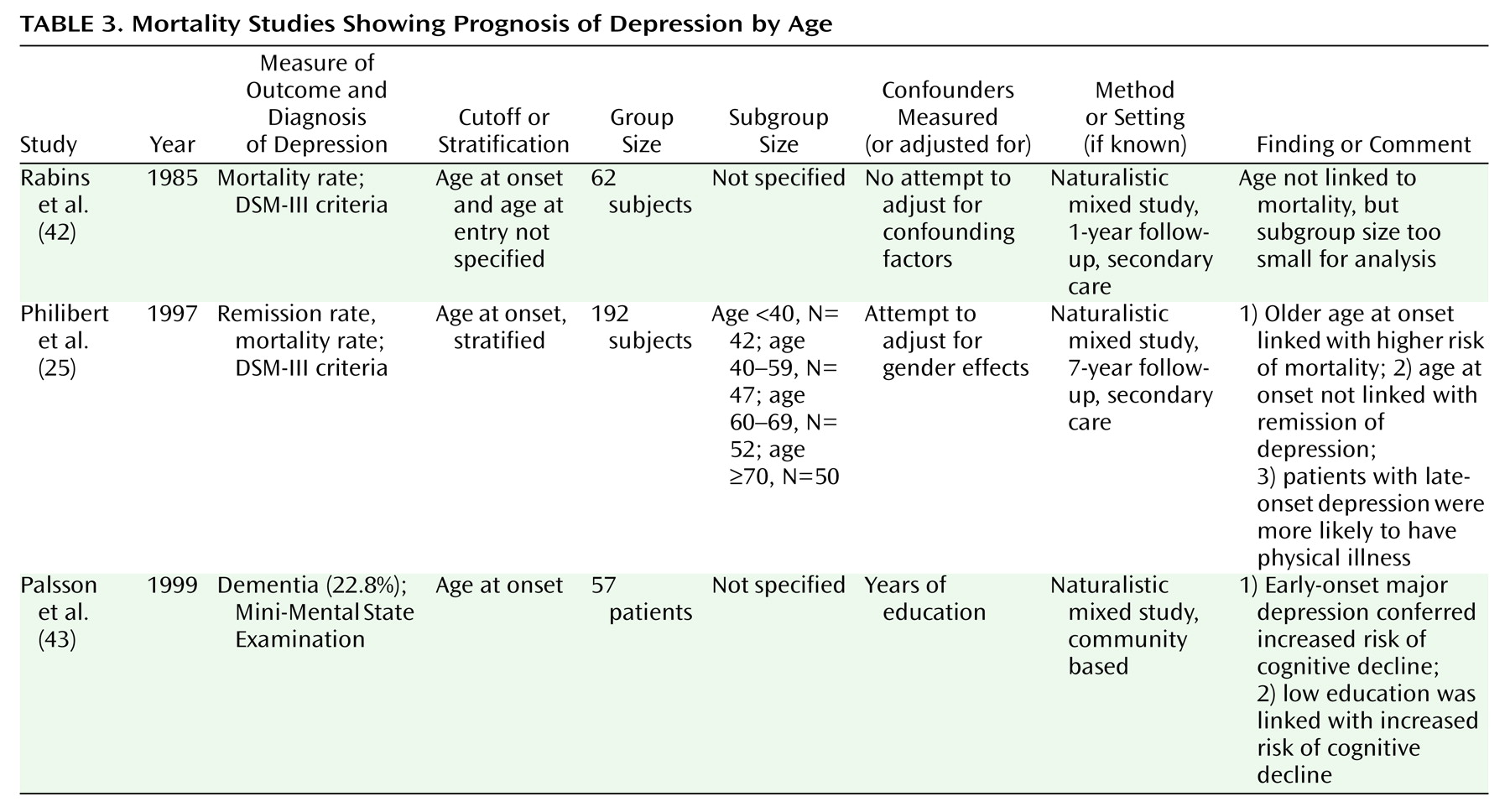

(38). It is already known that age is a risk factor for dementia, but it is intriguing that an early age at onset (and, hence, a long illness duration) of depression might confer additional risk

(43). Additionally, there are hints that patients who go on to develop dementia may respond worse to treatment at baseline

(28,

68). It is of interest to note that both late age at onset and older chronological age appear to greatly increase the likelihood of medical comorbidity

(25,

37). The clinical implication is that older patients with comorbidity are likely to require more prolonged treatment with antidepressants. Given that older patients may experience a different side effect profile than younger patients

(69), antidepressant choice must also reflect agents that are well tolerated in the medically ill older population

(70,

71).

In summary, the balance of evidence appears to support the notion that depression in the elderly is equally responsive to initial treatment but has a more adverse longitudinal trajectory than depression in middle age. However, this effect is probably accounted for by factors such as previous episodes and medical comorbidity. If future studies recruit subjects from across the life span rather than concentrating on a narrow age range, our understanding of the complex course of depression will improve. In addition, more attention should be given to the influence of duration of untreated depression on later prognosis. It is already clear that the link between outcome of depression and age is more complex than it first appears, which serves to remind clinicians of the importance of assessing all factors associated with aging and not just age itself.