Measures

During each interview, we assessed the occurrence over the previous year of 12 depressive symptoms lasting at least 5 days and representing the disaggregated nine symptoms of criterion A for major depression in DSM-III-R (insomnia, hypersomnia, appetite/weight gain, appetite/weight loss, psychomotor retardation, and restlessness were assessed as six separate symptoms). Participants used a 5-point scale to indicate the degree to which each symptom interfered with their daily life, which served as a measure of symptom severity (from 0, absence of the symptom, to 4, symptom interfering completely with daily life). Interviewers probed to ensure that each symptom was not due to medication or physical illness. Participants were then asked which symptoms co-occurred, and the interviewer aggregated these symptoms into co-occurring syndromes. We define dysphoric episode as any syndrome in which two or more of the nine symptoms of DSM-III-R criterion A co-occurred. This level of depressive symptoms has been shown to be associated with substantial psychosocial and role impairment

(14,

15) . We did not require the presence of a large number of symptoms (e.g., five of nine) because we wanted to analyze subthreshold depressive episodes first, and we did not require the presence of any specific symptoms (e.g., sadness or anhedonia) because such an approach would bias the very phenomena—symptom profiles—under investigation. However, in a follow-up analysis, we restricted our sample to those who met full criteria for major depression (see Statistical Analysis below). If more than one dysphoric episode occurred within the previous year, we analyzed the one the participant identified as being the worst. Test-retest reliability was assessed in 119 individuals who experienced a dysphoric episode and who were interviewed twice by different interviewers (average interview interval of 30 days [SD=9]) and was found to be adequate: the average weighted kappa coefficient across the 12 symptoms was 0.47, and the average polychoric correlation coefficient was 0.72.

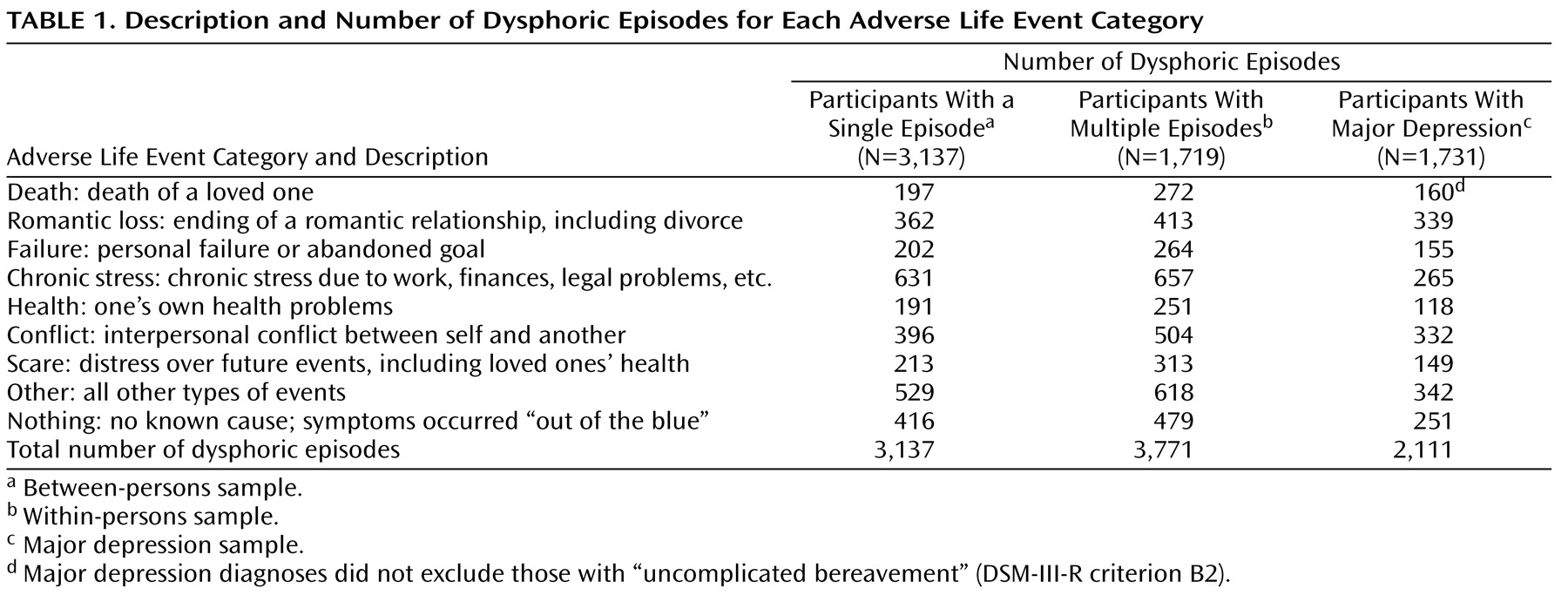

For each dysphoric episode, participants were asked, “During this period, did something happen to make you feel that way or did the feeling just come on you ‘out of the blue’?” If participants could think of a cause, they were asked to describe it. Interviewers assigned these responses to one of several hundred specific causal codes. When participants indicated multiple causes (21% of the time), they ordered them by causal importance. For this study, we collapsed the primary (first) causal codes into nine ALE categories (

Table 1 ). Thus, each dysphoric episode was associated with a single ALE category for a given wave, although different ALE categories could and often did occur across waves for the same person. A list of the correspondence between the nine broad ALE categories and the specific causal codes is available at the first author’s web site (http://matthewckeller.com/html/publications.html). In the 119 individuals who experienced a dysphoric episode and who were interviewed twice by different interviewers, the test-retest reliability of the ALE categories was adequate, with a kappa coefficient of 0.51.

To control for mood in the previous 30 days, respondents completed the depression and anxiety subscales of the Revised Symptom Checklist-90

(16) . This information was missing for 731 dysphoric episodes (11%) because it was not collected for one of the waves; its mean value was substituted when it was missing, although a follow-up analysis also dropped these subjects (see below). We used an adapted version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R

(17) to make diagnoses of major depression in the previous year.

Statistical Analysis

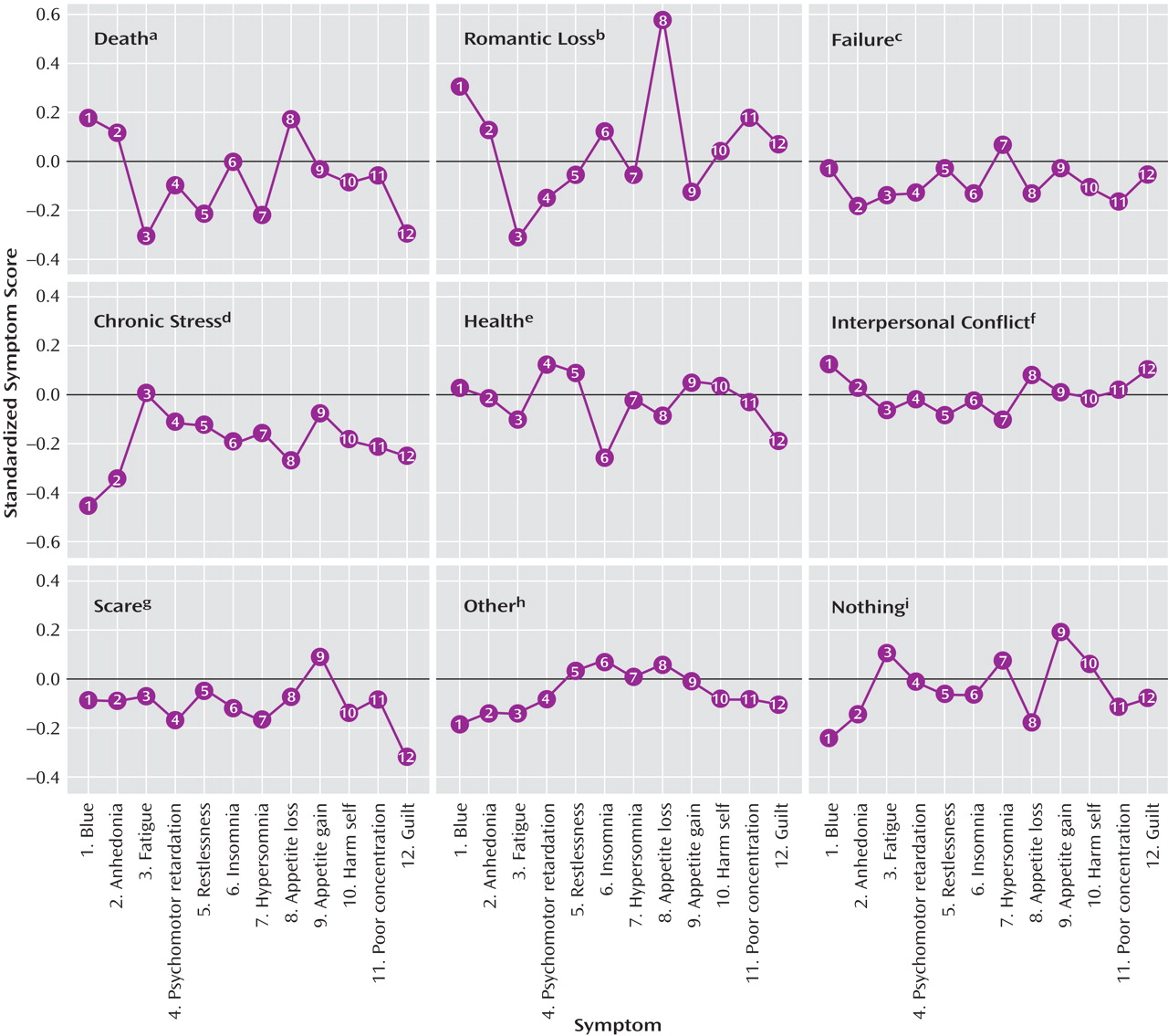

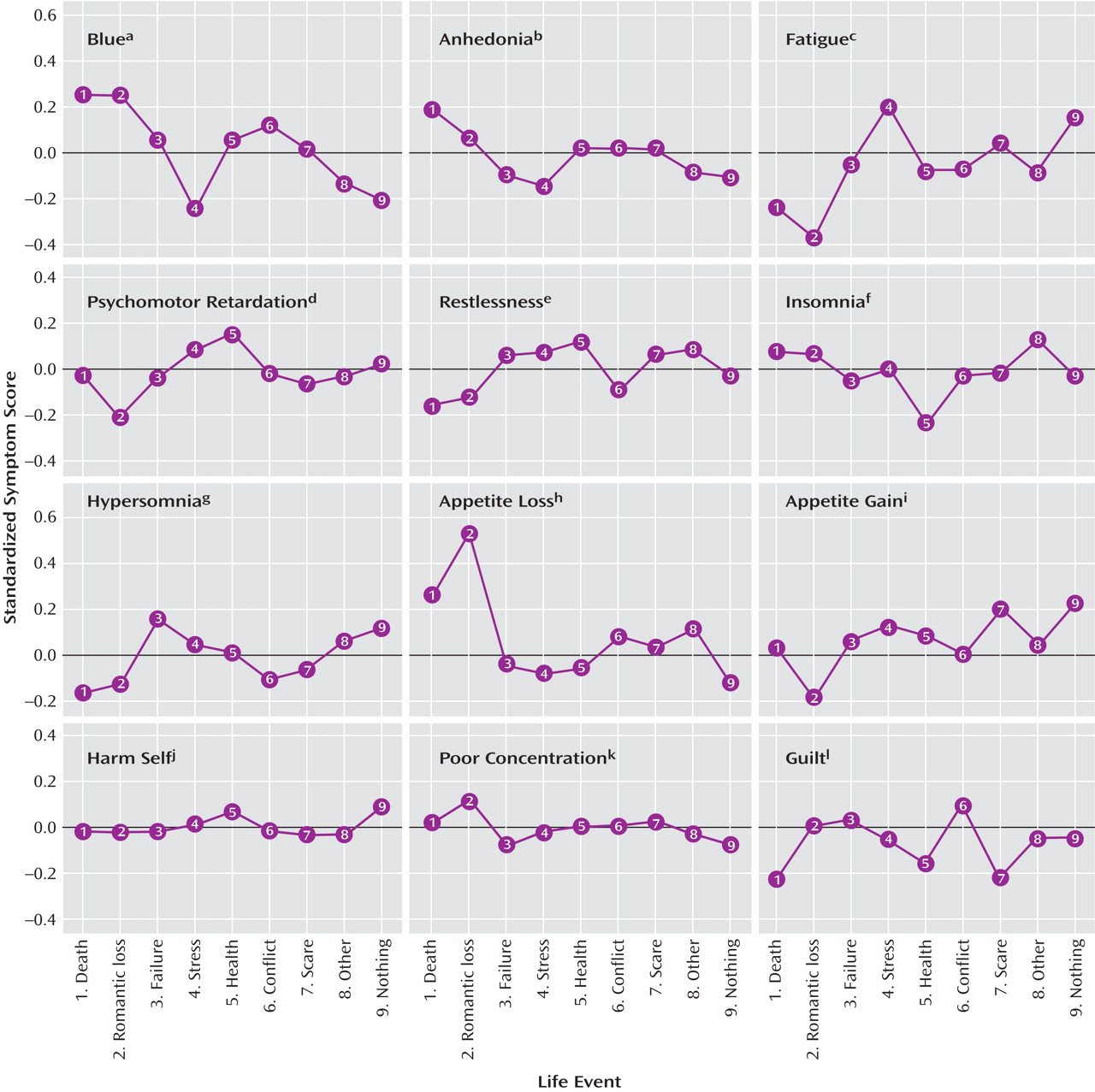

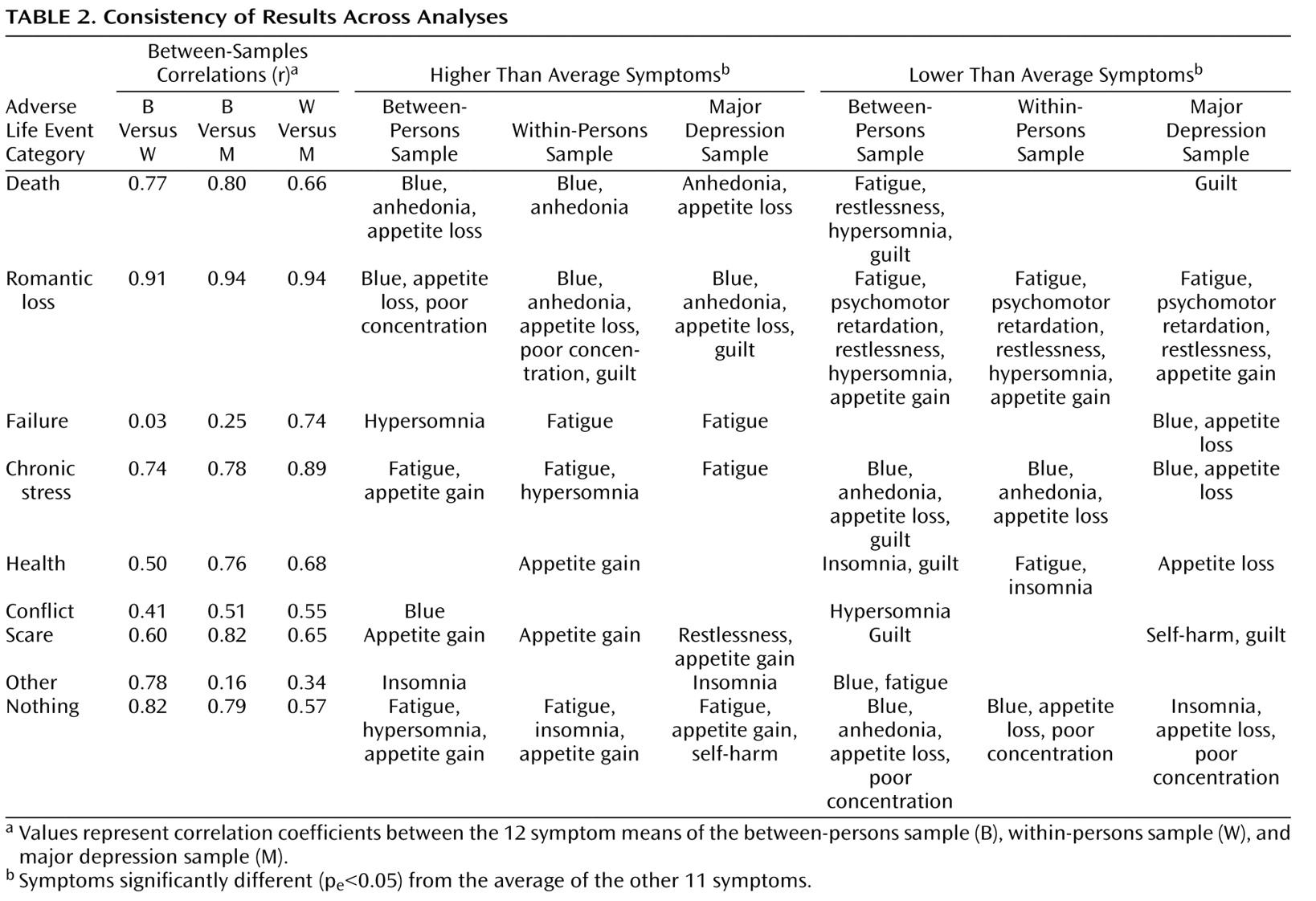

We conducted three analyses. The first was restricted to the 3,137 individuals (the between-persons sample) who experienced only one dysphoric episode or who experienced multiple dysphoric episodes all caused by the same ALE category. Among participants who experienced multiple episodes caused by the same ALE category, we randomly selected one for analysis. The dependent variables for this analysis were the 12 standardized symptom scales.

The second analysis was restricted to the 1,719 individuals (the within-persons sample) who experienced two or more dysphoric episodes across waves that were caused by two or more different ALE categories. There were 3,771 dysphoric episodes in the within-persons sample. To control for stable interpersonal differences in mean symptom levels, the dependent variables for the primary analysis of this sample were 12 within-persons symptom deviations: a participant’s symptom levels from a given episode subtracted from the symptom means across all episodes for that participant. For comparability with the between-persons sample results, we also performed a supplementary analysis on the (nondeviation) standardized symptom scales from this sample. The within-persons and between-persons samples were mutually exclusive, so tests on them are essentially independent.

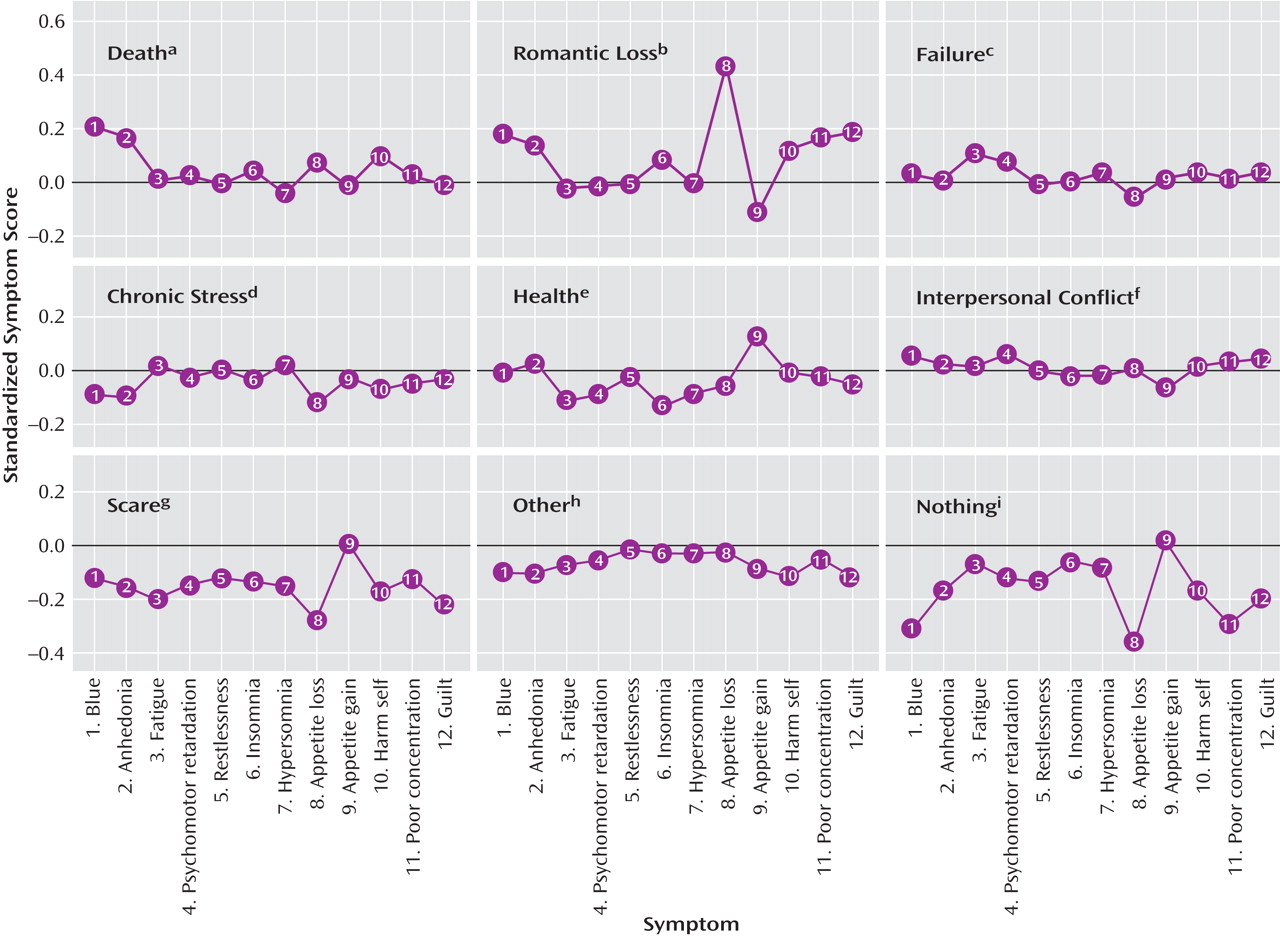

The third analysis was restricted to the 1,731 individuals (the major depression sample) from both the within-persons and the between-person samples whose dysphoric episodes met full DSM-III-R criteria for major depression. This sample was therefore not independent of the first two samples. We randomly selected one episode for analysis among participants who experienced multiple depressive episodes caused by the same ALE category, although we allowed multiple episodes from the same person if they were caused by different ALE categories. The dependent variables were the 12 standardized symptom scales.

For each analysis, we conducted an omnibus test and several follow-up contrasts (described in Results). The omnibus prediction that different ALE categories are associated with different depressive symptom patterns was tested by the ALE-by-symptom interaction term in a repeated-measures multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). The 12 standardized depressive symptoms (in the analyses of the between-persons sample and the major depression sample) or the 12 standardized depressive symptom deviations (in the within-persons analyses) served as repeated-measures dependent variables, and the nine categorical ALE categories served as between-subjects predictor variables.

For valid statistical inference, MANOVA requires multivariate normality of the residuals, equality of the variance-covariance matrices of the dependent variables across the levels of the predictors, and independence of the residual terms. In our data, none of these assumptions was met. For example, multiple data entries from the same family (across twins) were present in all three analyses. To generate valid inferential statistics despite these violations of assumptions, we derived all p values of inferential statistics empirically, via permutation testing, based on 10,000 runs. These empirical p values are denoted p e . We permuted the data accounting for its nested dependencies (e.g., multiple episodes nested within individuals nested within twin pairs).

Given that so few of the symptom data were missing (<0.1% in all data sets), we imputed missing symptom data using an expectation maximization algorithm developed by Schafer

(18) . We used an approximation to the F statistic (a transformation of Wilks’s lambda developed by Rao

[19] ) as the inferential statistic from MANOVA analyses. All tests controlled for age, gender, duration of the dysphoric episode, and depression and anxiety in the previous 30 days. The results did not substantively change when tests did not control for these variables or when episodes with any data missing on the independent, dependent, or control variables were removed. The results were also similar when we conducted separate tests on men versus women, and on participants who were younger versus older than the median age. The statistical software used for all analyses was “R,” version 2.1.1

(20) .