Only female-female twin pairs were included in this investigation because biometric modeling was not possible for social phobia in male subjects due to low prevalence rates. The prevalence of categorical diagnoses of avoidant personality disorder in our study group was also too low to permit useful analysis. We therefore used a dimensional approach

(25), constructing ordinal variables based on the number of endorsed criteria. To optimize statistical power and produce maximally stable results, we used a number of subthreshold criteria (³1), assuming that the liability for each trait was continuous and normally distributed, i.e., that the classification (0–3) represented different degrees of severity. This assumption was evaluated using multiple threshold tests for each of the criteria. The same procedure was used to test the assumption that the total number of positive criteria for avoidant personality disorder represented different degrees of severity. All of the multiple threshold tests were done separately for each zygosity group, and none was significant (all p values >0.05). Because the number of subjects who endorsed all or most of the criteria for the disorder was small, we collapsed the upper categories for the total summed score, resulting in an ordinal variable that included four subcategories.

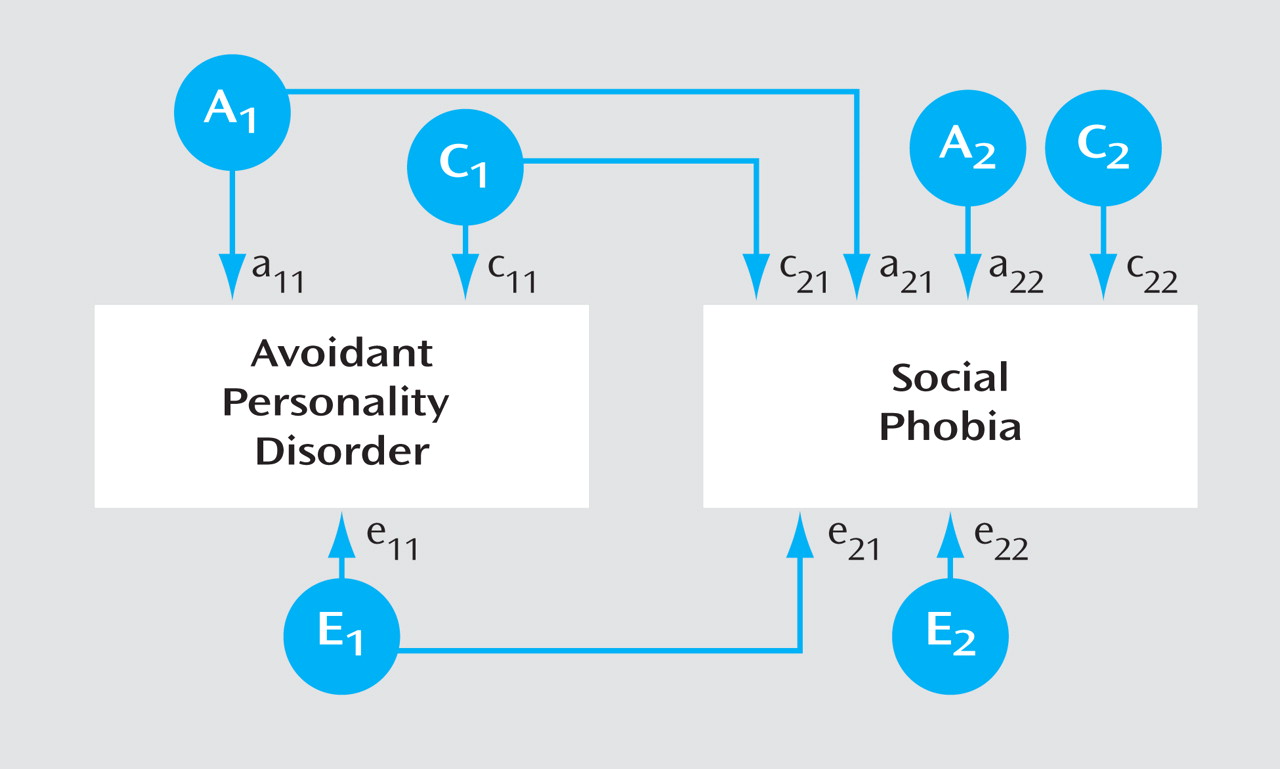

In the classical twin model used in this study, individual differences in liability are assumed to arise from three latent factors: additive genetic factors (A) (i.e., genetic effects that combine additively); common or shared environmental factors (C), including all environmental exposures that are shared by the twins and contribute to their similarity; and individual-specific or unique environmental factors (E), including all environmental factors not shared by the twins, plus random measurement error. Because monozygotic twins share all their genes and dizygotic twins share on average 50% of their segregating genes, genetic factors (A) contribute twice as much to twin resemblance for a particular trait or disorder in monozygotic twins compared with dizygotic twins. Both monozygotic and dizygotic twins are assumed to share all of their C factors and none of their E factors.

Model fitting was performed using the Mx statistical program

(26) . To test the degree to which the covariation between social phobia and avoidant personality disorder resulted from common factors, we applied a bivariate Cholesky structural equation model

(27), specifying three latent factors (A

1, C

1, and E

1 ) with pathways influencing both avoidant personality disorder (a

11, c

11, e

11 ) and social phobia (a

21, c

21, e

21 ), in addition to three factors (A

2, C

2, and E

2 ) accounting for residual influences specific to social phobia only (a

22, c

22, e

22 ) (

Figure 1 ). Pathways a

21, c

21, and e

21, from A

1, C

1, and E

1, respectively, represent genetic and environmental effects shared by both phenotypes. The choice of ordering was based on the assumption that avoidant personality disorder should be the “upstream” variable because it is by definition a stable lifelong trait, whereas social phobia, although often a chronic disorder, could be episodic

(8) . This model permitted the calculation of correlations between genetic factors (r

a ), shared environmental factors (r

c ), and unique environmental factors (r

e ) that influence the two phenotypes. A full model, including all latent variables (ACE), was compared with nested submodels with reduced numbers of parameters. The fit of the alternative models was compared using the difference in twice the log likelihood values, which under certain regular conditions is asymptomatically distributed as χ

2, with degrees of freedom (df) equal to the difference in the number of parameters. According to the principle of parsimony, models with fewer parameters are preferable if they do not result in a significant deterioration of fit. A useful index of parsimony is Akaike’s information criterion, which is calculated as Dc

2 –2Ddf

(28) .

A basic assumption in traditional twin analysis is that monozygotic and dizygotic twins are equally correlated in their exposure to trait-relevant environments. We tested the validity of this assumption by applying polychotomous logistic regression and controlled for the correlational structure of our data using independent estimating equations, in accordance with SAS procedure GENMOD

(29) . Two variables that reflected similarity in childhood and adult environments, respectively, were constructed. In each twin pair we tested whether the avoidant personality disorder score or social phobia status in twin 1 interacted with our measure of environmental similarity in predicting the avoidant personality disorder score or social phobia status in twin 2. We controlled for the effects of zygosity, sex, age, and level of environmental similarity, as well as shared environmental effects and genetic effects. None of the four analyses testing the impact of environmental similarity on twin resemblance for avoidant personality disorder and social phobia approached significance (all p values >0.10).