Patients with major depressive disorder often also suffer from anxiety, nervousness, and the somatic correlates of these states

(1) . In patients with high levels of anxiety accompanying major depression, greater severity of depressive illness and functional impairment

(2), greater illness chronicity

(3), and an increased risk of suicidality

(4) have been reported.

Although DSM-IV

(5) does not recognize anxious depression as a diagnostic subtype, emerging evidence suggests a number of distinguishing features for this potential subtype

(2,

3,

6) . In outpatients with major depression, earlier studies reported lifetime comorbidity rates of 40%–50%

(7,

8) for anxiety disorders. More recently, in two distinct large subsamples of outpatients with major depression in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) project

(6,

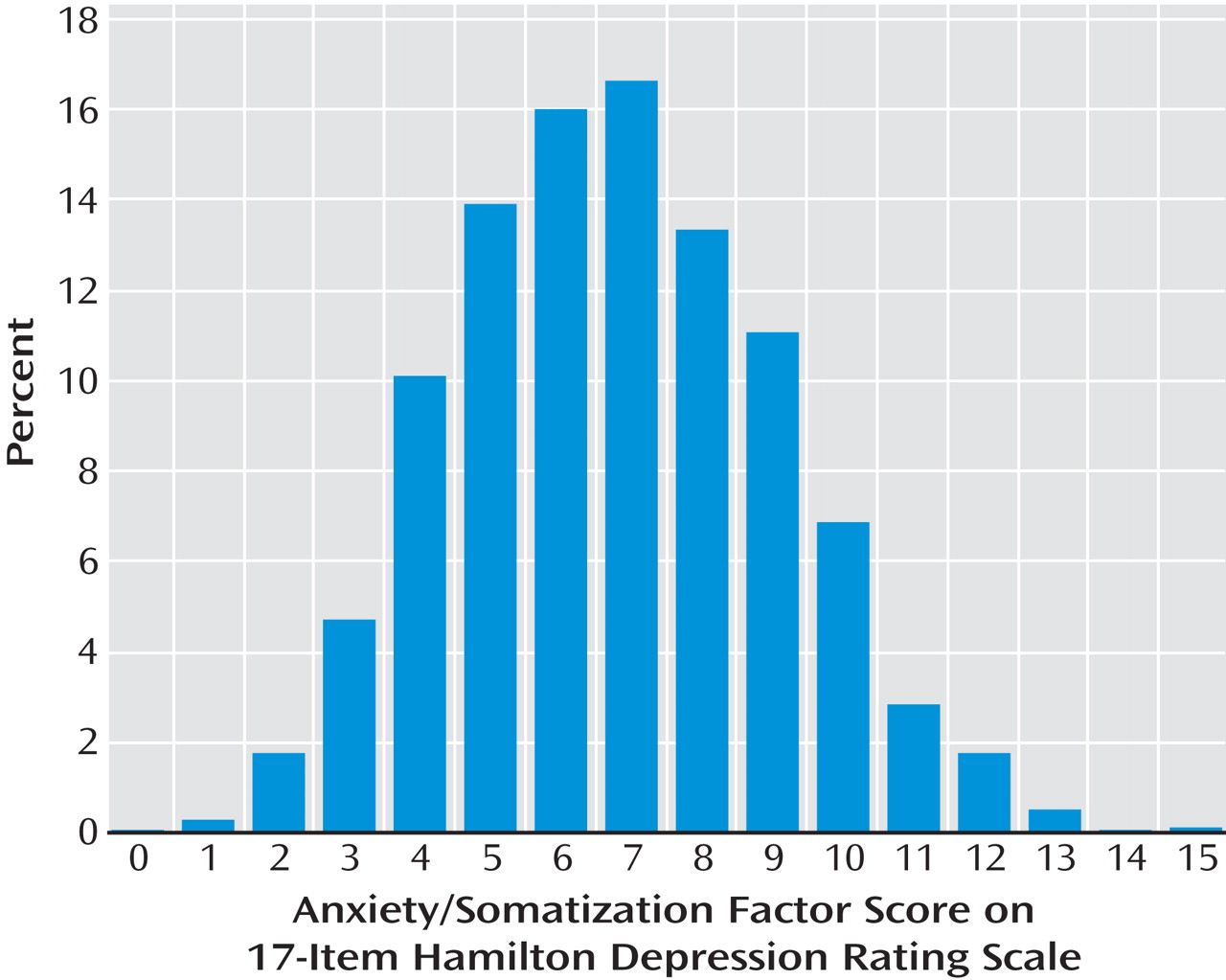

9), the proportion with anxious depression (those having a baseline 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAM-D] anxiety/somatization factor score ≥7) was in the range of 44%–46%. In both subsamples, patients with anxious depression were significantly more likely to be unemployed, to have less education, to be more severely depressed, to have more concurrent anxiety disorders, and to report more melancholic/endogenous features, even after adjustment for severity of depression.

Previous research has also shown that individuals experiencing major depressive disorder with high levels of anxiety symptoms have a slower response to treatment

(10) and, in some

(11 –

13) but not all

(4,

14) short-term studies, are less likely than those without high levels of anxious symptoms to respond to antidepressant treatment, regardless of the type of antidepressant used. The association between anxious depression and poorer response to antidepressant treatment may account for the results of a study showing that the concomitant use of anxiolytics or sedative/hypnotics was a significant predictor of treatment resistance in older adults with depression

(15) .

On the basis of the available literature, we hypothesized that patients with anxious depression would be significantly less likely than patients with nonanxious depression to respond to, or achieve remission with, antidepressant treatment. We tested these hypotheses by examining treatment outcomes with antidepressant treatment in patients with anxious versus nonanxious major depression in Levels 1 and 2 of the STAR*D study.

Method

Study Overview and Organization

The rationale, design, and methods of STAR*D have been detailed elsewhere

(16,

17) . Briefly, STAR*D aimed to determine prospectively which of several treatments would be most effective for outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder who have an unsatisfactory clinical outcome with an initial treatment and, if necessary, subsequent treatment(s). Participants were enrolled at 18 primary care and 23 specialty care settings across the United States. Three-quarters of the facilities were privately owned, and about one-third were hospital based. Clinical research coordinators at each site assisted participants and clinicians in protocol implementation and collection of clinical measures. A central group of research outcome assessors conducted telephone interviews to obtain primary outcome measure data.

Study Population

Prior to study entry, all risks, benefits, and potential adverse events associated with participation in the study were explained to participants, who provided written informed consent in a protocol approved by institutional review boards.

To enhance the generalizability of findings, study eligibility was limited to self-declared outpatients (no symptomatic volunteers) seeking treatment and identified by their clinicians as having major depressive disorder requiring treatment. Advertising for symptomatic volunteers was proscribed. Broadly inclusive selection criteria were used

(16,

17) . For eligibility, patients had to be 18–75 years of age, meet DSM-IV criteria for single or recurrent nonpsychotic major depressive disorder (established by treating clinicians and confirmed by a DSM-IV checklist), have a score ≥14 (indicating moderate severity) on the 17-item HAM-D

(18) as rated by a clinical research coordinator, and not have been treatment resistant in an adequate trial of an antidepressant during the current episode. Exclusion criteria have been described elsewhere

(16,

17) .

Definition of Anxious Depression

As in our previous studies

(6,

9,

19), anxious depression was defined as major depressive disorder with high levels of anxiety symptoms, as reflected in a HAM-D anxiety/somatization factor score ≥7. The anxiety/somatization factor, derived from Cleary and Guy’s

(20) factor analysis of the HAM-D scale, includes six items from the original 17-item version: the items for psychic anxiety, somatic anxiety, gastrointestinal somatic symptoms, general somatic symptoms, hypochondriasis, and insight. We used the baseline HAM-D score (obtained by research outcome assessors) to assess for the presence of anxious depression.

Baseline Measures

At baseline, clinical research coordinators collected standard demographic information, self-reported psychiatric history, and current general medical conditions as evaluated by the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale

(21) . They administered the HAM-D and assessed depressive symptoms using the clinician-rated 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS-C); patients completed the self-report version of the QIDS (QIDS-SR)

(22 –

25) . Patients also completed the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire

(26,

27), which is used to assess for the presence of 11 potential concurrent DSM-IV disorders. Based on prior reports

(26), we used thresholds with a 90% specificity in relation to the gold-standard diagnosis rendered by a structured interview to define the presence of concomitant axis I disorders. Current general medical conditions were assessed by the 14-item Cumulative Illness Rating Scale

(21,

28) ; for this instrument, a manual

(29) was used to guide scoring.

The research outcome assessors, blind to treatments and working from locations separate from clinical sites, conducted telephone interviews to complete the HAM-D and the 30-item clinician-rating version of the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology

(23,

30) . Responses to items on these measures were used to estimate the presence of atypical

(31), melancholic

(32), and anxious

(6) symptom features.

An interactive voice response system

(33) was used to collect data from patients on their health perceptions (with the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey

[34] ), quality of life (with the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire

[35] ), and occupational and interpersonal adjustment (with the Work and Social Adjustment Scale

[36] ).

Course of Treatment Measures

An integral part of our measurement-based care intervention

(37) was the collection, at each visit, of clinically relevant information to inform treatment decision making. At each clinic visit, the QIDS-C and QIDS-SR ratings were obtained, and side effects were assessed using three 7-point scales to rate their frequency, intensity, and global burden

(17,

38) .

Intervention

The aim of citalopram treatment in Level 1 was to achieve symptom remission, which was defined as QIDS-C score ≤5. The protocol

(17) required a fully adequate dose of citalopram for a sufficient time to maximize the likelihood of achieving remission, so those who did not achieve remission were truly resistant to the medication.

Dose adjustments were guided by recommendations in a treatment manual (www.star-d.org) that allowed individualized starting doses and dose adjustments to minimize side effects, maximize safety, and optimize the chances of therapeutic benefit for each patient. Citalopram was to begin at 20 mg/day and be raised to 40 mg/day by weeks 2–4 and to 60 mg/day (final dose) by weeks 4–6. Dose adjustments were guided by how long a patient had received a particular dose, symptom changes, and side effect burden.

The protocol recommended treatment visits at 0, 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12 weeks, with an optional visit at week 14 if needed. After an optimal trial of citalopram (based on dose and duration), patients whose symptoms responded or remitted could enter the 12-month naturalistic follow-up phase, but all who did not achieve remission were encouraged to enter the next randomized trial in the STAR*D sequence (Level 2). Patients could discontinue citalopram before 12 weeks if intolerable side effects made a medication change necessary, if an optimal dose increase was not possible because of side effects or patient choice, or if significant symptoms (as indicated by a QIDS-C score ≥9) were present after 9 weeks at maximally tolerated doses. Patients could opt to move to the next treatment level if they had intolerable side effects or if their QIDS-C score was >5 after a trial of adequate dosage and duration. A treatment manual, initial didactic instruction, ongoing support and guidance by the clinical research coordinator, the use of a structured evaluation of depressive symptoms and side effects at each visit, and a centralized treatment monitoring and feedback system together represented an intensive effort to provide consistent, high-quality care (

37 ; see also www.star-d.org).

Safety Assessments

To monitor side effects and serious adverse events, a multitiered approach

(39) was used, involving the clinical research coordinators, the study clinicians, the interactive voice response system, the clinical manager, safety officers, regional center directors, and the National Institute of Mental Health’s Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

Concomitant Medications

Concomitant treatments for current general medical conditions, for associated symptoms of depression (e.g., sleep and agitation), and for citalopram’s side effects were permitted, based on clinical judgment, at study entry or during the treatments.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the HAM-D score, obtained by research outcome assessors using telephone-based structured interviews at entry and exit from citalopram treatment. Secondary outcome measures included the QIDS-SR and the rating scale for frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects at baseline and at each treatment visit.

Statistical Analysis

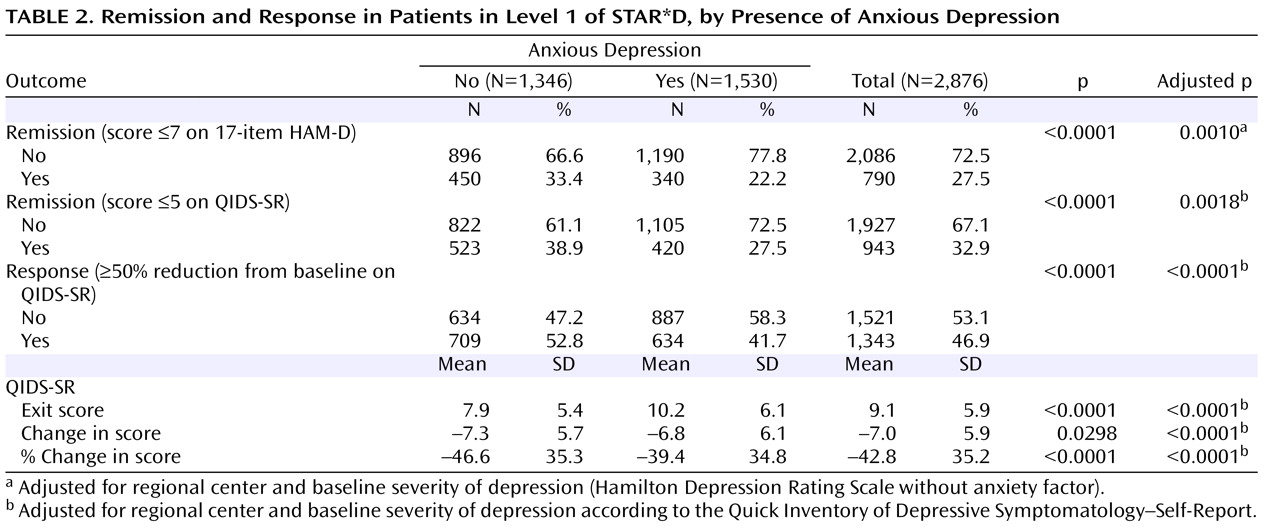

Remission was defined as an exit HAM-D score ≤7 or last observed QIDS-SR score ≤5. As defined in the original study proposal, patients for whom the exit HAM-D score was missing were designated as not achieving remission. Response was defined as a reduction of ≥50% from baseline in the QIDS-SR score at the last assessment. Intolerance was defined a priori as either leaving treatment before 4 weeks or leaving at or after 4 weeks with intolerance as the identified reason. The alpha level in analyses was set at 0.05 (two-sided). No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

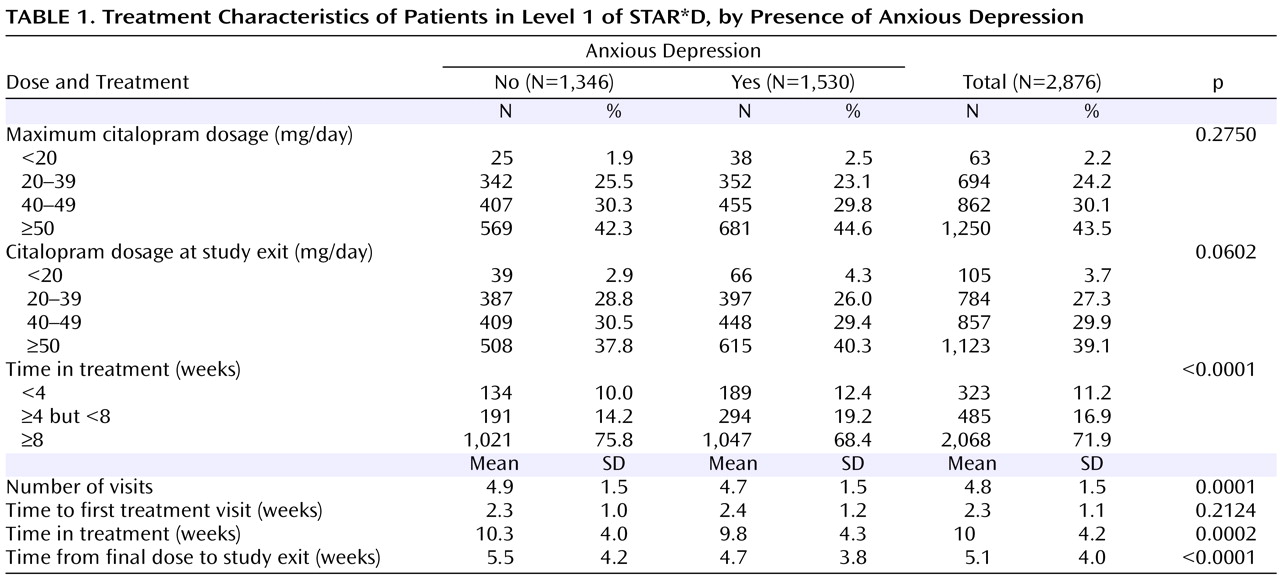

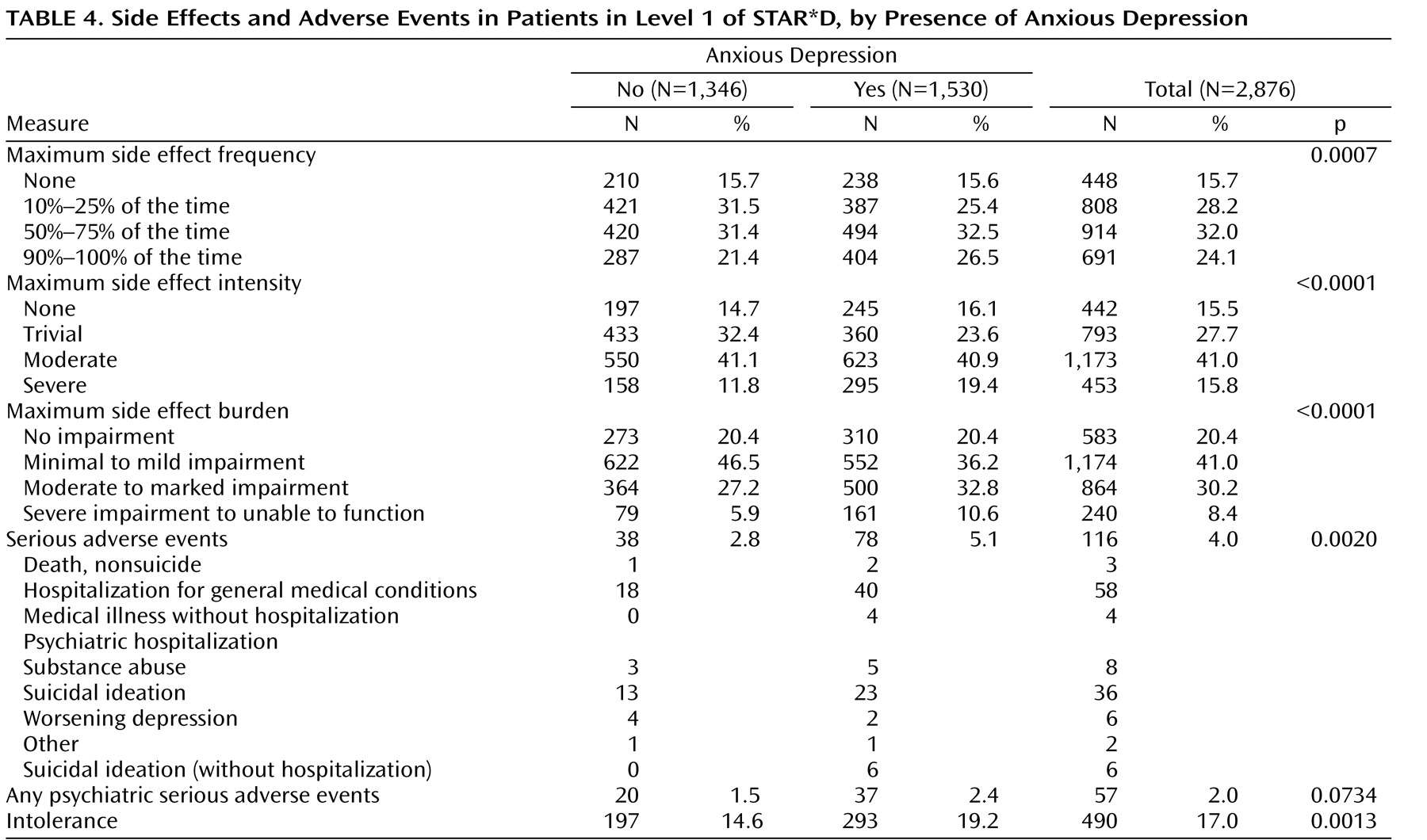

Baseline clinical and demographic features, treatment features, and rates of side effects and serious adverse events were compared between patients with anxious and nonanxious depression. Student’s t tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were used for continuous variables, and chi-square tests were used for discrete variables.

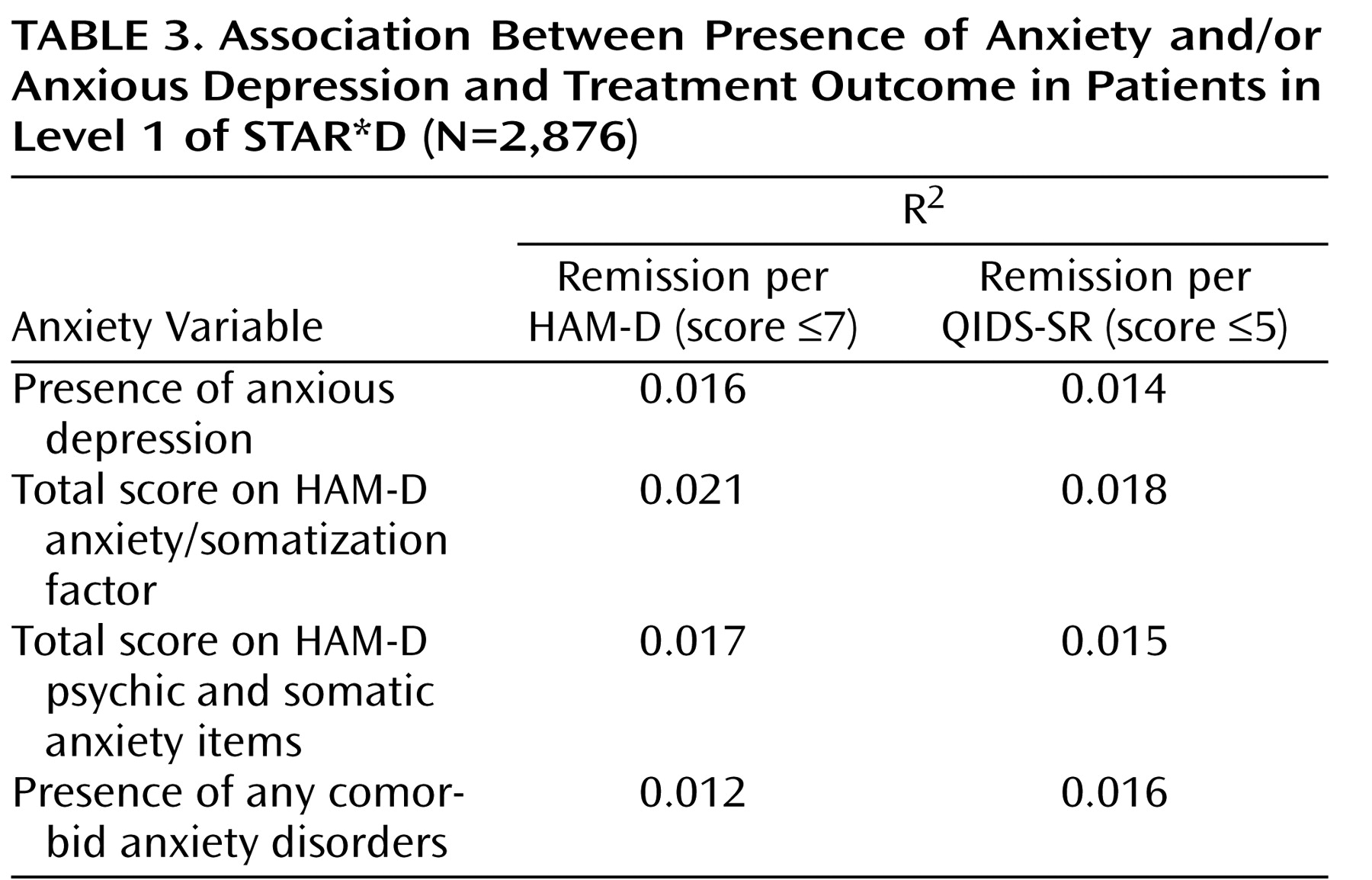

Logistic regression models were used to compare remission and response rates after adjustment for baseline severity of depression (as measured by the QIDS-SR) and regional center. Bivariate logistic regression models were used to examine the association of remission rates (using both the HAM-D and the QIDS-SR criteria) with several independent variables: presence of anxious depression; total score on the HAM-D anxiety/somatization factor; total score on the HAM-D psychic and somatic anxiety items; and presence of any comorbid anxiety disorder.

Cross-tabulations of remission (as measured by either the HAM-D or the QIDS-SR criteria) with each possible threshold on the HAM-D anxiety/somatization factor were obtained, and the sensitivity and specificity at each threshold were calculated and graphed.

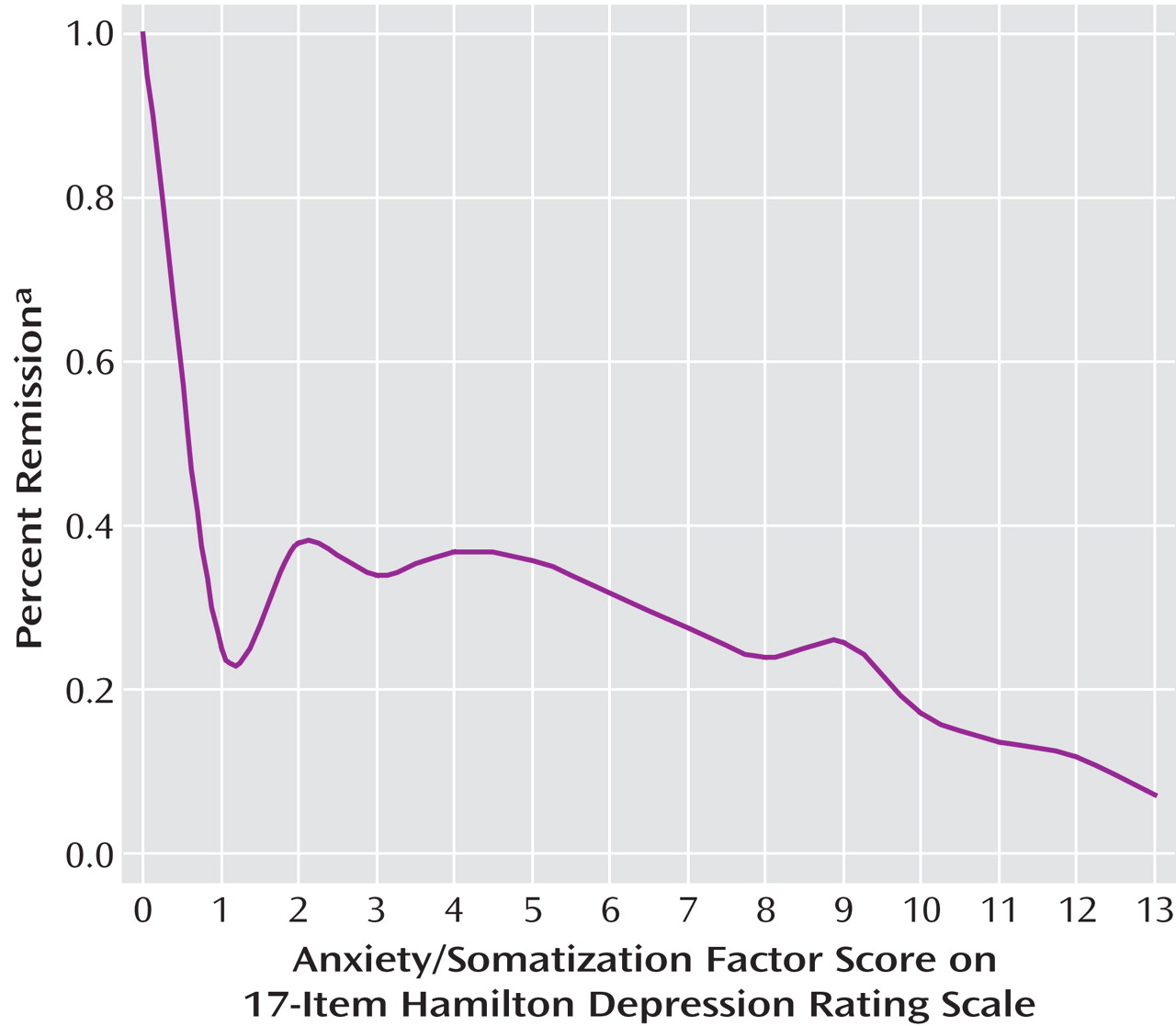

We also plotted the number of anxiety symptoms based on the HAM-D anxiety/somatization factor versus the percentage of patients who achieved remission according to either the HAM-D or the QIDS-SR criteria.

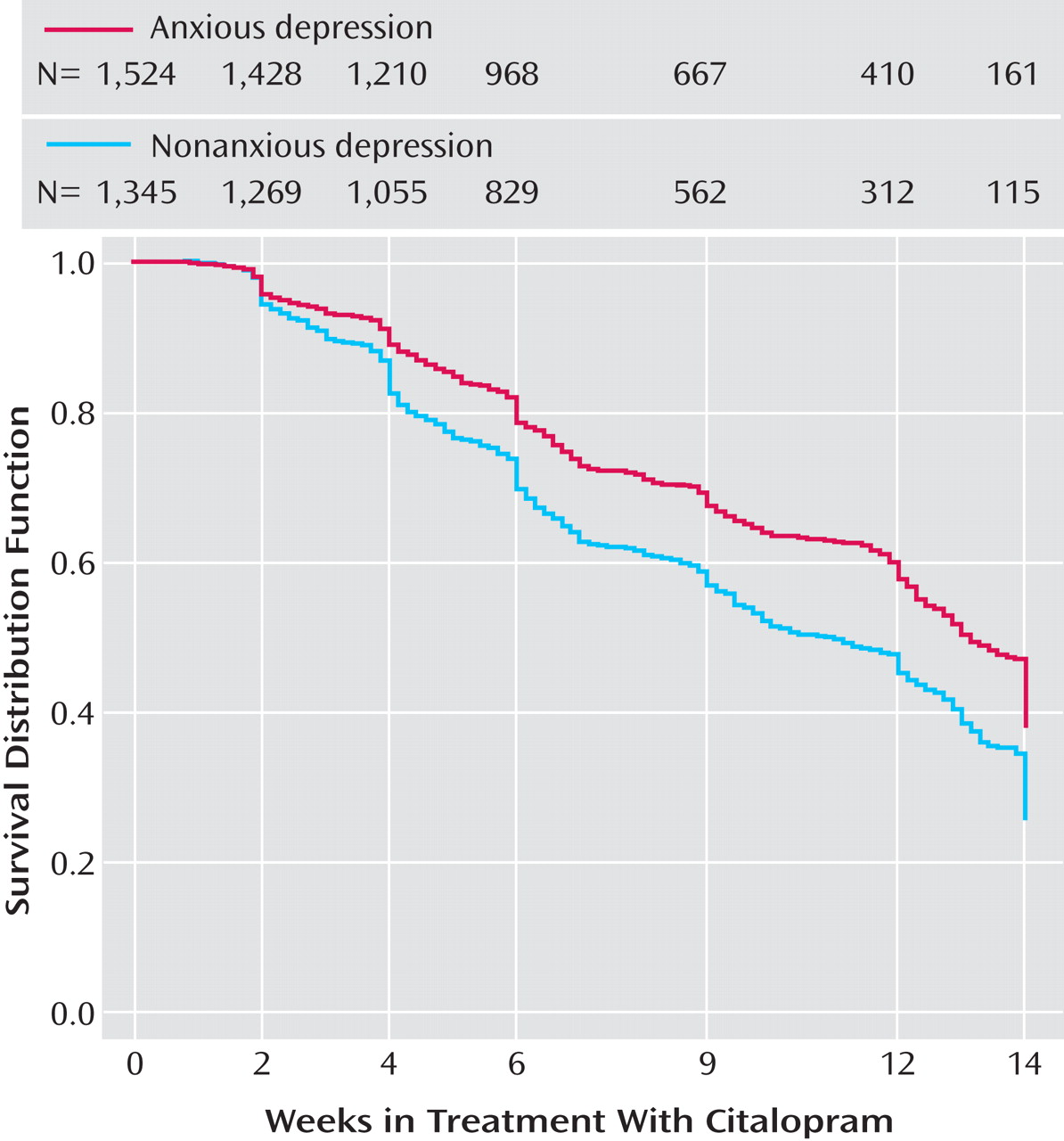

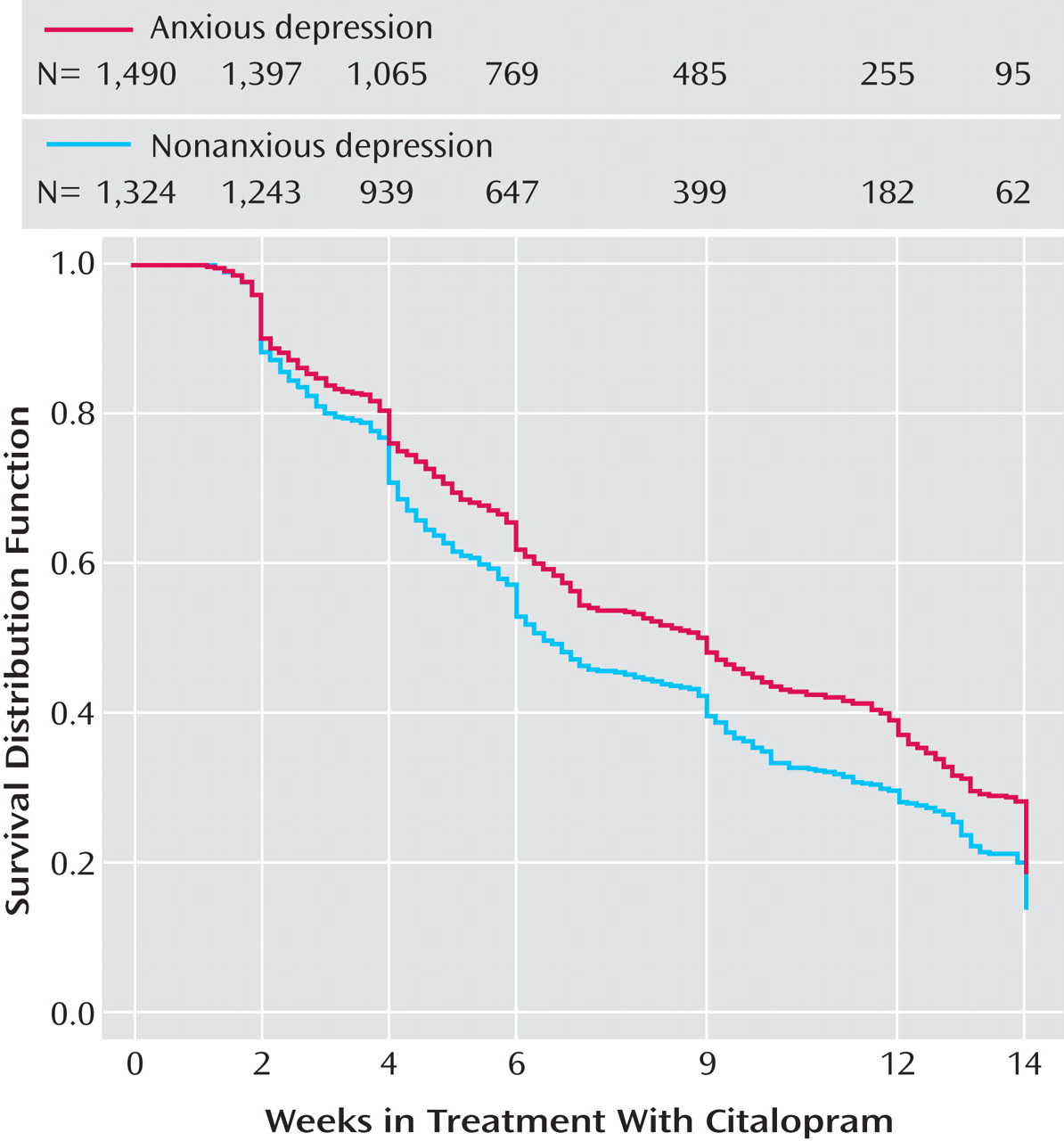

Time to first remission (with remission defined as a QIDS-SR score ≤5) and time to first response (≥50% reduction from baseline QIDS-SR score) were defined as the first observed point in clinic visit data. Log-rank tests were used to compare the cumulative proportions of patients with and without anxious depression whose symptoms remitted or responded.

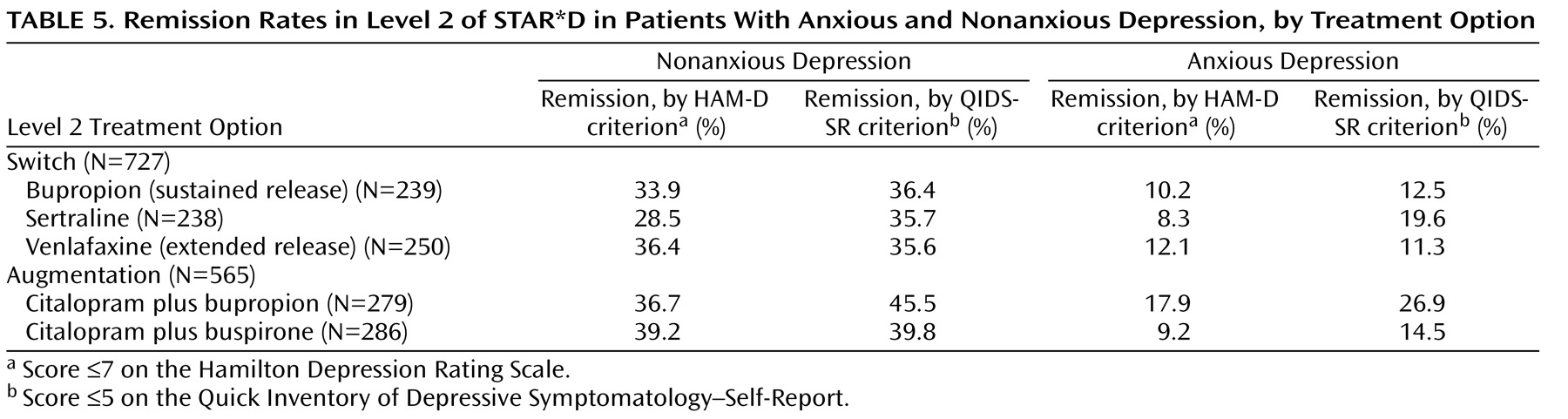

We ran logistic regression models with remission (based on the HAM-D or QIDS-SR cutoffs) in Level 2 as the outcome and with treatment, presence of anxious depression, and the two-way interaction as the independent variables.

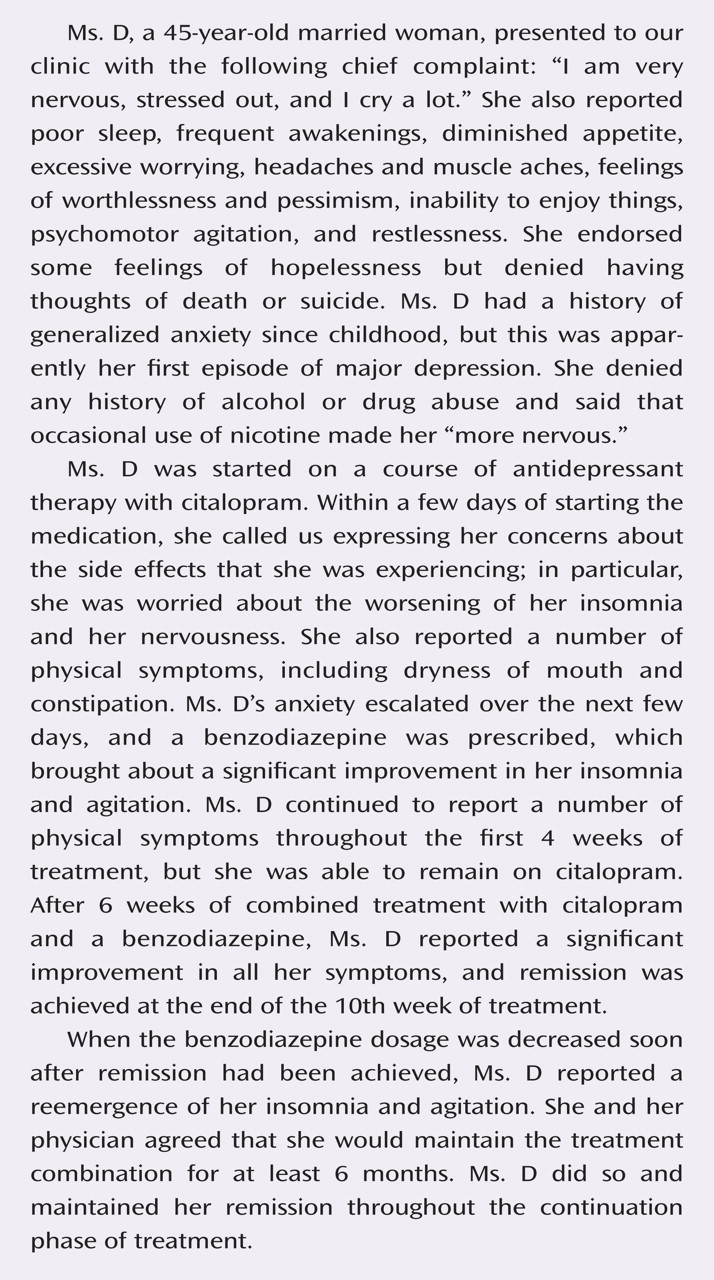

Discussion

This is the largest sample used thus far to examine whether major depression with anxious features is associated with a different treatment outcome than nonanxious major depression. Consistent with much of the literature

(10 –

13), we found in Level 1 of STAR*D that patients with anxious depression were less likely to respond or to remit with citalopram treatment than those with nonanxious depression. Overall, they also took longer to remit. This association between anxious depression and poorer treatment outcomes with citalopram held true regardless of how we defined anxious depression. Results of all the logistic regression models we used to assess this association showed that the average R

2 values ranged from 0.014 to 0.020, with the total score of the HAM-D anxiety/somatization factor being the best predictor, followed closely by the total score of the HAM-D psychic and somatic anxiety items, and then by whether anxious depression was present (as defined by a HAM-D anxiety/somatization factor score ≥7); the worst predictor was whether any concurrent anxiety disorders were present. Although these data and the relatively linear decline in remission rates with increasing anxiety factor scores (

Figure 2 ) may seem to suggest that the anxious/somatic factor should be viewed more as a continuous dimension than a dichotomous subtype, one might argue that there is a certain clinical utility in the use of a threshold value and that the dichotomy performed well enough in our regression analyses.

In Level 2 of STAR*D, patients with anxious depression were also less likely than those with nonanxious depression to achieve remission, regardless of whether their Level 2 treatment was a switch option or an augmentation option. This is the first time that a predictor of poorer outcome with antidepressant treatment in a population without any prior history of treatment resistance has been confirmed in a population with prospectively defined resistance or intolerance to antidepressant treatment.

The lower HAM-D remission rates observed in the anxious depression group could be due in part to residual symptoms of anxiety, which may have increased the HAM-D score, since this scale comprises several anxiety symptom items. On the other hand, lower remission rates for anxious depression in both Levels 1 and 2 of STAR*D were also observed with the QIDS-SR, which measures only core symptoms of major depression and does not include any items measuring anxiety symptoms.

Side effect frequency, intensity, and burden in Level 1 were greater among patients with anxious depression than among those with nonanxious depression, as were serious adverse events, including those of a psychiatric nature. In addition, both time in treatment and time on the final citalopram dosage were significantly lower in the anxious than in the nonanxious depression group, although these differences were small. Perhaps patients whose illness included anxious features were more sensitive to somatic changes occurring during antidepressant treatment, and they may have been more likely to drop out on encountering side effects. These adverse event findings are interesting, as they suggest that this difference may reflect physical vulnerability rather than a difference in the interpretation of discomfort.

These findings, taken together with our two previous STAR*D reports on anxious depression

(6,

9), have several practical implications for the recognition and diagnosis of anxious depression. The presence of certain clinical and sociodemographic characteristics should alert us to the possibility that anxiety may be a prominent feature of a patient’s major depressive disorder. As recommended by Robins and Guze

(42) and later expanded on by Kendler

(43), a distinct psychiatric diagnostic entity may be considered valid if it can be shown to have differentiating features, evidence of familiality, specific treatment responsivity, and a unique course. In this and our two previous studies

(6,

9), anxious depression appeared to be associated with a characteristic clinical profile, independent of severity of depression. As for familiality, we did not obtain any family history of anxious depression, so we could not assess whether this subtype of depression runs in families. Our results are consistent with the view that anxious depression is associated with specific treatment responsivity, in that patients with this subtype were less likely to achieve remission than those with nonanxious depression after antidepressant treatment, in both Levels 1 and 2 of STAR*D, regardless of treatment assignment in Level 2. Although more data are needed to provide information on the specific treatment responsivity and on the familiality of this condition, the findings of this study, combined with those of our previous studies, are supportive of the view that anxious depression might be a valid diagnostic subtype of major depressive disorder. Our results also suggest the need for additional emphasis on the measurement of symptoms of anxiety during the acute management of patients with major depression, particularly those whose symptoms are resolving only slowly and those who continue to exhibit residual symptoms after an adequate antidepressant trial

(44) .

This study had several limitations that should be taken into account in interpreting the results and recommendations. Our definition of anxious depression was based on the severity of anxiety symptoms as measured by the HAM-D anxiety/somatization factor. Although the HAM-D does include anxiety items and its anxiety/somatization factor has been used in a number of previous studies, it captures only a limited number of anxiety symptoms. Therefore, the possibility of a significant risk of misclassification cannot be ruled out. On the other hand, the association between anxious depression and poorer treatment outcome with antidepressant monotherapy in Level 1 of STAR*D held true regardless of how we defined anxious depression. Another limitation is that we did not use a clinician-administered structured diagnostic interview, which might have provided a more accurate diagnostic picture. Also, since only outpatients with major depression were enrolled in the study, the clinical correlates and symptom patterns we found to be associated with anxious depression may be different in inpatients treated for depression. Furthermore, in the absence of a placebo control, we cannot determine whether these patients are specifically less responsive to true drug effects or less responsive to the nonspecific aspects of treatment. In addition, participants were enrolled from a number of sites in a nonrandom manner. Finally, patients with anxious depression had a higher physical illness burden, lower socioeconomic status, greater severity of depression, and later onset of depression, all of which could themselves be associated with poorer treatment outcome. It is possible that more severe or more difficult-to-treat forms of depression are accompanied by high levels of anxiety and therefore that high levels of anxiety in depression are simply an epiphenomenon of these other forms of depression and do not represent a different subtype. Similarly, it is possible that the greater side effect burden in the group with high levels of anxiety could be explained by the greater number of general medical conditions in this group.