Depressive disorders are highly prevalent

(1,

2) and have a high incidence

(3), and they are associated with a substantial loss of quality of life for patients and their relatives

(4,

5), increased mortality rates

(6), high levels of service use, and enormous economic costs

(7 –

9) . Major depression is currently ranked fourth worldwide in disease burden, and it is expected to rank first in disease burden in high-income countries by the year 2030

(10) .

There are two ways to reduce the enormous disease burden from depressive disorders: treatment of existing disorders and prevention of new cases. By far the most research has been conducted on the treatment of depressive disorders, and relatively few studies have focused on possibilities for preventing the onset of new cases of depression

(11) . Recent studies from Australia, however, have shown that existing pharmacological and psychological treatments cannot reduce the burden of disease of depressive disorders by more than 35%, even under ideal circumstances

(12,

13) .

Prevention has been examined in a considerable number of intervention studies, but only a small proportion of these have focused on possibilities for actually preventing the onset of new cases of mental disorders

(14) . Most prevention trials have measured change in protective factors, such as social, cognitive, or problem-solving skills, or in intermediate outcomes, such as severity of depressive symptoms. In recent years, however, a growing number of studies have examined whether prevention programs are actually capable of reducing the incidence of cases of mental disorders as defined by diagnostic criteria. This is an important research question, both from a public health perspective and from a scientific perspective. Prevention is important because duration of the disorder is inversely related to outcome, so that by the time cases come to the attention of practitioners, they are harder to treat. If prevention is effective, it can be employed in concert with treatment in efforts to curtail the burden of disease associated with depression. From a scientific point of view, prevention is equally interesting, as it may result in knowledge about the processes leading up to the onset of depressive disorders and how interventions may curtail or delay these processes.

Although a growing number of studies have examined the effects of preventive interventions on the incidence of depressive disorders, no meta-analysis of these studies has been conducted. An earlier meta-analysis examined the effects of psychological prevention programs on the incidence of all mental disorders

(14) . At that time, however, only a small number of studies (N=6) of the effects on depressive disorders could be included; in the past few years many new studies have been conducted, and in this meta-analysis we were able to include 19 studies. We focused on the effects of preventive interventions on the incidence of major depressive disorder. We also examined whether any factors can be identified that modify the effects of prevention.

Results

Description of Included Studies

We retrieved a total of 135 articles that potentially met our inclusion criteria. Of these, 116 were excluded, 81 because the presence of depressive disorders was not assessed with a formal diagnostic interview, 13 because they were treatment and not prevention studies, 17 because they did not examine psychological interventions, and five for other reasons (articles that described the design of studies without results or articles with insufficient data).

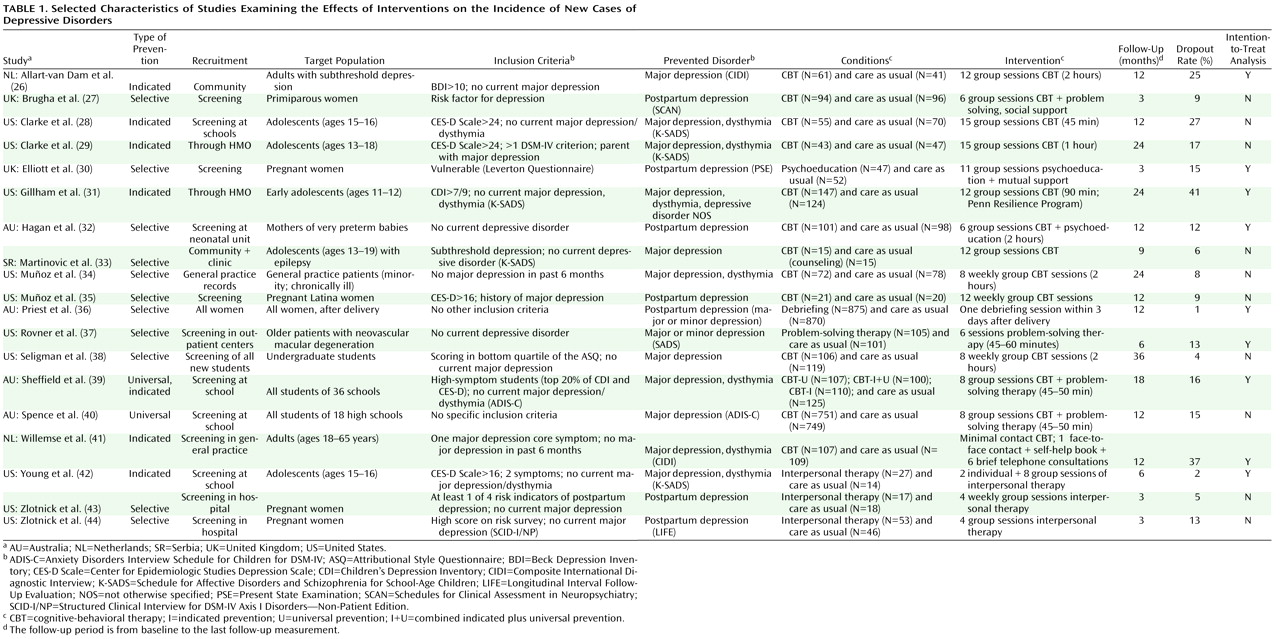

A total of 19 studies

(26 –

44) met all inclusion criteria; because one of these studies used three different preventive interventions and a control group, a total of 21 comparisons could be made between a preventive intervention group and a control group. The total number of respondents in the studies was 5,806 (3,014 in the intervention conditions and 2,792 in the control conditions). Selected characteristics of the included studies are presented in

Table 1 .

Seven of the 19 studies were designed to prevent postpartum depression, four dealt with prevention in school settings, two were aimed at patients with a physical disorder, two focused on primary care patients, and the remaining studies were aimed at other target groups. Seven studies focused on adolescents, and 12 targeted adults (one focusing on older adults). In 14 studies, subjects with a diagnosed depressive disorder at baseline were excluded, while the interventions in the remaining five studies (aimed at high-risk groups) did not assess the presence of a depressive disorder at baseline. Of the 14 studies in which subjects with a diagnosed depressive disorder at baseline were excluded, 12 excluded those with a current depressive disorder and two excluded those who had a depressive disorder in the previous 6 months.

We distinguished three types of prevention

(45) : universal prevention, such as school programs and mass media campaigns, aimed at the general population or segments of the general population, regardless of whether they have a higher-than-average risk of developing a disorder; selective prevention, aimed at individuals in high-risk groups who have not yet developed a mental disorder; and indicated prevention, aimed at individuals who have some symptoms of a mental disorder but do not meet diagnostic criteria. Two of the 21 contrast groups we included in our meta-analysis examined universal prevention, 11 examined selective prevention, and eight examined indicated prevention. Fifteen interventions were cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), three were interpersonal psychotherapy, and the remaining were other types of intervention (one-session debriefing; problem-solving; and mutual support). In 18 comparisons, a group format was used, and the remaining three comparisons used an individual format. The number of sessions ranged from one to 15.

The follow-up periods in the different studies ranged from 3 to 36 months. Ten studies were conducted in the United States, four in Australia, two in the United Kingdom, two in the Netherlands, and one in Serbia.

Although the quality of the included studies was relatively high, the criteria assessing the validity of the studies did not indicate very positive results. Only seven studies reported allocation to conditions by an independent party. Blinding of assessors of outcomes was reported in eight of the 19 studies. Dropout rates ranged from 1% to 41%. In nine studies, intention-to-treat analyses were conducted.

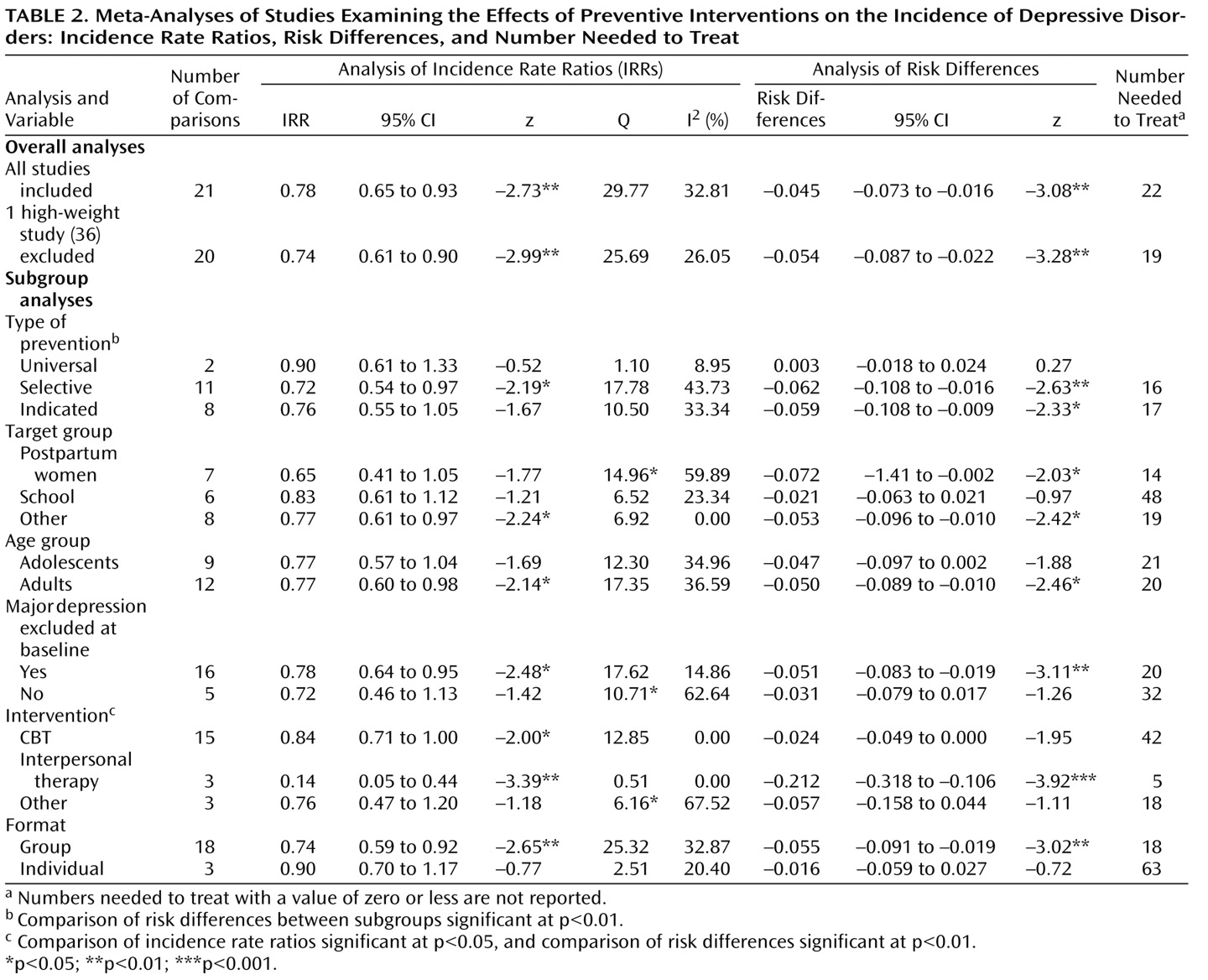

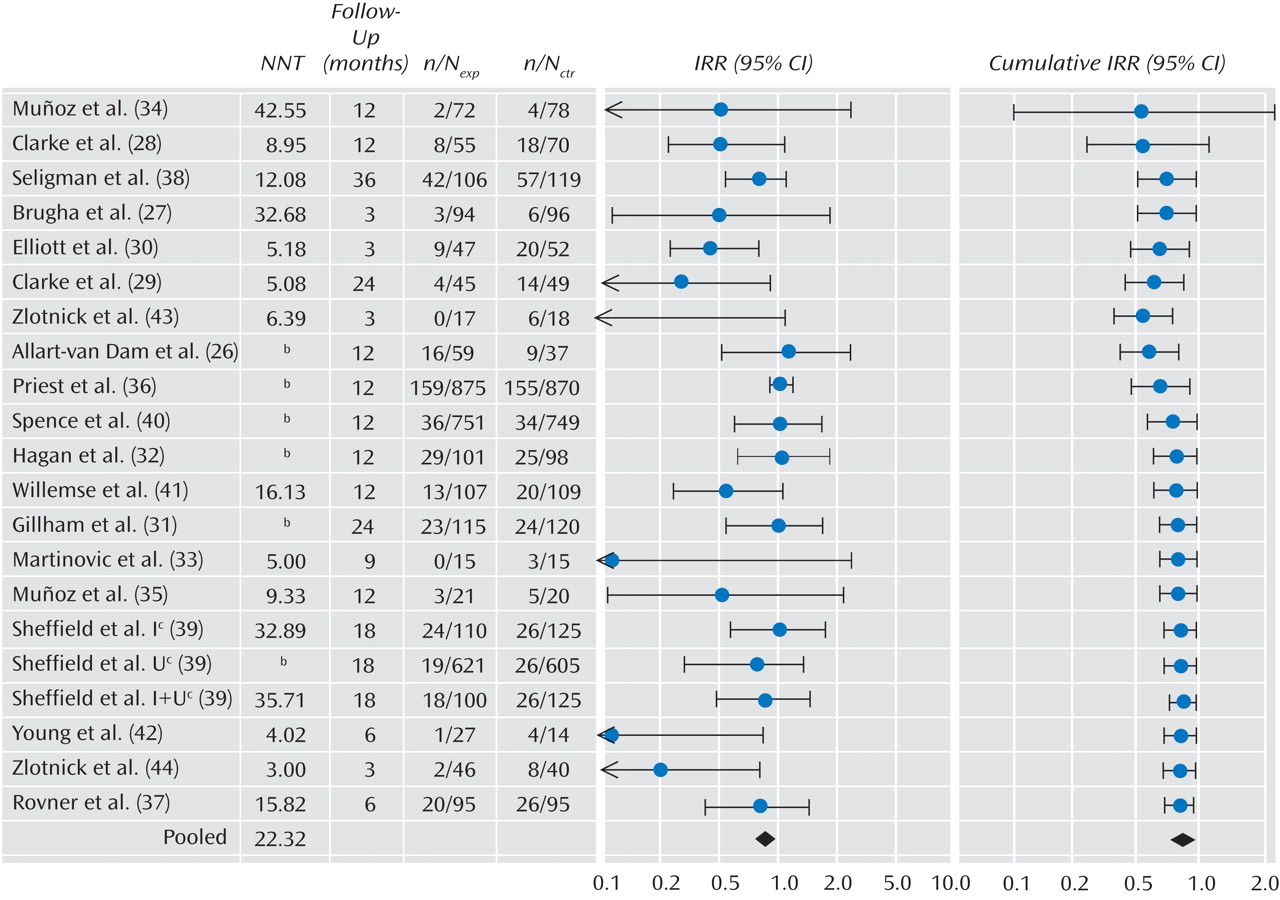

Incidence Rate Ratios

The mean incidence rate ratio for all 21 comparisons from the 19 studies was 0.78 (95% confidence interval [CI]=0.65–0.93), which was significant (p<0.01). Heterogeneity was low to moderate (Q=29.77, p<0.10; I

2 =32.81%). The results of this meta-analysis are summarized in

Table 2 and

Figure 1 . The cumulative meta-analysis showed that the overall results became significant after the first four studies had been published in 2000 (

Figure 1 ).

Because the weight of one study

(36) was very high (34.2%), and because this was also the study in which a very different type of intervention was used (one-session debriefing after childbirth), we examined whether removal of this study from the analysis would change the overall results. The resulting mean incidence rate ratio was 0.74 (95% CI=0.61–0.90, p<0.01), with low heterogeneity (Q=25.69, n.s.; I

2 =26.05%), which is comparable to the incidence rate ratio found in the analyses with the full sample.

In one large study

(39), three intervention conditions were compared with one control group. Because these three comparisons were not independent from each other, we examined whether removal of these comparisons would increase heterogeneity. The resulting mean incidence rate ratio was 0.74 (95% CI=0.59–0.92, p<0.01; Q=28.79, p<0.05; I

2 =40.95%).

Neither the funnel plots nor Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill procedure suggested a significant publication bias. The incidence rate ratio did not change after adjustment for possible publication bias (the observed and adjusted effect sizes were the same).

Risk Differences and Number Needed to Treat

Our analyses were based on the assumption of an underlying constant hazards model in both groups, which may not be the case. We conducted several sensitivity analyses. We calculated the odds ratio for each study (ignoring the differences in follow-up period between the studies) and pooled them. The resulting odds ratio was 0.76 (95% CI=0.62–0.94; z=–2.59, p=0.01), which was comparable to the earlier analyses.

We also calculated the absolute risk differences for each study (again ignoring the differences in follow-up period). This resulted in a pooled risk difference of –0.045 (95% CI=–0.073 to –0.016, p<0.01), which corresponds to a number needed to treat of 22 (

Table 2 ). The numbers needed to treat for each study are presented in

Figure 1 .

Subgroup and Metaregression Analyses

Because some heterogeneity was observed, we conducted a series of subgroup and metaregression analyses. The results of the subgroup analyses are presented in

Table 2 . We examined whether the incidence rate ratio differed according to type of prevention (universal, selective, or indicated), target group (postpartum depression, students, or other), and age group (adolescents or adults). We also examined whether the studies in which subjects with a depressive disorder were excluded at baseline differed significantly from those in which high-risk groups were included without the exclusion of diagnosed cases. Then we examined whether type of intervention (CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy, or other) and format of the intervention (group or individual) were related to the incidence rate ratio.

As indicated in

Table 2, the incidence rate ratio differed significantly in only one subgroup. Studies in which interpersonal psychotherapy was used as an intervention appeared to be significantly more effective than those in which CBT or other interventions were used. Given the small number of comparisons (N=3) examining interpersonal psychotherapy, however, these results should be interpreted with caution.

In most of the subgroup analyses, heterogeneity was low or low to moderate. The subgroups of studies using CBT interventions or interpersonal psychotherapy showed no evidence of heterogeneity. Studies using other interventions had moderate to high heterogeneity, as might have been expected.

We conducted the same subgroup analyses based on the risk differences. As indicated in

Table 2, the type of intervention was again found to be associated with significant differences between subgroups. However, in these analyses, we also found that the different types of prevention (universal, selective, or indicated) differed significantly from each other (p<0.01).

Because universal prevention appeared to differ significantly from selective and indicated preventions, and prevention based on interpersonal psychotherapy differed significantly from the preventions used in the other studies, we conducted another subgroup analysis in which we excluded the two comparisons based on universal prevention and the three comparisons based on interpersonal psychotherapy. The resulting incidence rate ratio was 0.82 (95% CI=0.70–0.98, p<0.05; Q=18.28, n.s.; I 2 =17.92%), and the risk difference in this subgroup of studies was –0.035 (95% CI=–0.063 to –0.007, p<0.05; Q=18.93, n.s.; I 2 =20.74%). The pooled odds ratio (in which we ignored the differences in follow-up period between the studies) was 0.81 (95% CI=0.67–0.98, p<0.05).

We conducted a metaregression analysis to examine the relationship between incidence rate ratio and follow-up period. We found that the follow-up period was inversely related to the incidence rate ratio, although the association did not reach statistical significance (p<0.10; the point estimate of the slope was –0.023; 95% CI=–0.050 to 0.004). This result can be interpreted as an indication that the effects of the intervention become smaller over longer follow-up periods, which may indicate that the preventive interventions delay the onset of disorders rather than preventing them altogether. We also conducted a metaregression analysis to examine whether the incidence rate ratio was related to the number of sessions used in the preventive intervention, but no significant relationship was found.

Discussion

We found clear indications that preventive interventions can significantly reduce the incidence of depressive disorders by 22% compared with treatment-as-usual control groups. This means that prevention should perhaps have a larger role in the further reduction of the disease burden of depressive disorders.

Although preventive interventions appear to be effective in reducing the incidence of depressive disorders, the numbers needed to treat seem to be rather high (22 in the overall analysis). On the other hand, there are no clear guidelines for what is a high number needed to treat and what is not

(46) . For example, the regular use of aspirin to reduce the risk of heart attack has become common practice, and the number needed to treat has been found to be 130

(46,

47) . The number needed to treat associated with the use of cyclosporine in the prevention of organ rejection has been found to be 6.3 and is considered a medical breakthrough of considerable practical importance. A number needed to treat of 22 to prevent the onset of a depressive disorder does not seem unreasonably high, and it is even more favorable if we focus on selective (number needed to treat=16) and indicated prevention (number needed to treat=17).

We found no evidence that the capability of preventive interventions to reduce the incidence of major depression depends on use of specific target groups, such as women at risk of postpartum depression and school interventions directed at students. We did find indications that universal interventions were less effective than selective and indicated interventions. However, universal interventions were examined in only two studies, and pooling of these studies or a comparison with selective or indicated interventions is not very meaningful. The mean incidence rate ratio for universal interventions was not significant and approached a value of 1.0, indicating an absence of effect.

Selective (incidence rate ratio=0.72) and indicated interventions (incidence rate ratio=0.76) had comparable effects. These findings are in agreement with a recent meta-analysis of preventive interventions aimed at depression in children and adolescents

(20) . Although that study examined the effects on depressive symptom severity rather than on incidence of depressive disorders, clear indications were found that selected and indicated programs had larger effects than universal programs.

We also found some indications that interventions using interpersonal psychotherapy were more effective than those using CBT. This result must be considered with caution, however, because interpersonal psychotherapy-based interventions were examined in only three studies. Furthermore, in a recent study of a preventive intervention aimed at adolescents, interpersonal psychotherapy and CBT interventions resulted in comparable effect sizes

(48) . If interpersonal psychotherapy-based interventions are indeed more effective, this may be related to the fact that this type of intervention focuses more directly on existing problems and high-risk situations than does CBT. For people in high-risk situations or with subthreshold symptoms, this may be exactly what they need.

It is not clear whether the preventive interventions actually reduced the incidence or only delayed onset. Because the follow-up period in most studies did not exceed 2 years, it cannot be concluded that incidence was actually prevented. In fact, we found that the length of the follow-up period was inversely associated with the incidence rate ratio; although not statistically significant, this relationship can be seen as an indication of effect decay over time, which could point to a delay of incidence rather than prevention. From a clinical perspective, both preventing and delaying onset are important. Actual prevention of new cases would of course be preferable, as it would result in avoidance of the disease burden of all prevented cases. Delay of onset is also important, however, because the disease burden of depression is high. Every year during which a potential depressive disorder can be avoided will result in considerably less suffering by patients and their families and may entail a reduction in economic costs.

This study had several limitations. First, the number of studies examining the effects of preventive interventions on the incidence of depressive disorders was relatively small, and the quality of the included studies was not optimal. Also, the included studies examined several different interventions and target populations. However, heterogeneity in our sample of studies was low to moderate, indicating that this may be a fairly homogeneous group of studies. The differences in follow-up periods across the studies constitute another limitation. To try to overcome this limitation, we calculated the number of new cases during follow-up in terms of person-time-based incidence rate ratios, but this approach assumes that the occurrence of new onsets was distributed evenly over the follow-up period. This assumption of an underlying constant hazards model in both groups may not be correct and may have resulted in an underestimation of the incidence rate ratio in the studies with longer follow-up periods or an overestimation in those with shorter follow-up periods. On the other hand, our sensitivity analyses indicated that our results were quite robust and that the underlying constant hazards model is probably acceptable for the relatively brief follow-up periods of the included studies. Because of these limitations, the results of this study should be considered with caution.

It is encouraging to find that prevention of new cases of depressive disorders seems to be feasible. Prevention may be an important way, in addition to treatment, to reduce the enormous burden of depression in the coming years.