Numerous studies have shown that childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is significantly associated with adolescent and adult substance use disorders

(1 –

8) . Additionally, stimulants are considered first-line treatments for children with ADHD

(9,

10) . Animal studies have raised concern regarding stimulant treatment because of findings of sensitization to the effects of drugs. The sensitization hypothesis, a neuroadaptional model, maintains that exposure to stimulants results in dopamine system alterations, which in turn increase sensitivity to the reinforcing effects of the previously experienced substance. Behavioral sensitization has been demonstrated in numerous mammalian species, including nonhuman primates, and has been found to be long lasting

(11,

12) . Consistent with this model, some studies have suggested that there may be a causal link between stimulant treatment in childhood and later substance use disorder

(13,

14) . The potential role of stimulants in the pathogenesis of substance use disorder is a major public health concern, since stimulant use is widespread and these medications are increasingly prescribed to young children

(15) . Of relevance to this controversy, some animal studies have reported developmental effects on stimulant sensitization. Specifically, later preference for cocaine in rats is decreased by early relative to later methylphenidate administration

(16,

17), suggesting that age at exposure may modulate long-term drug effects on the brain, at least in rats.

More than one dozen studies have examined the association between stimulant treatment of ADHD and substance use disorder

(18 –

20) and, with one exception

(21), have not found a significant positive relationship. In non-ADHD children treated with methylphenidate or placebo, we also did not find a relationship between exposure to methylphenidate and substance use disorder in adulthood

(22) . To our knowledge, no study has examined the association between age at first exposure to stimulants and later substance use disorder. The objective of the present study was to examine possible relationships between age at initiation of methylphenidate treatment and the later development of substance use disorder. The data presented are on a clinic sample of male children with ADHD who were prospectively followed and systematically assessed in late adolescence

(3,

4) and adulthood

(5,

6) by blinded clinicians. Stimulant treatment began as early as age 6 for some children and as late as age 12 for others.

Results

Predictor Variables

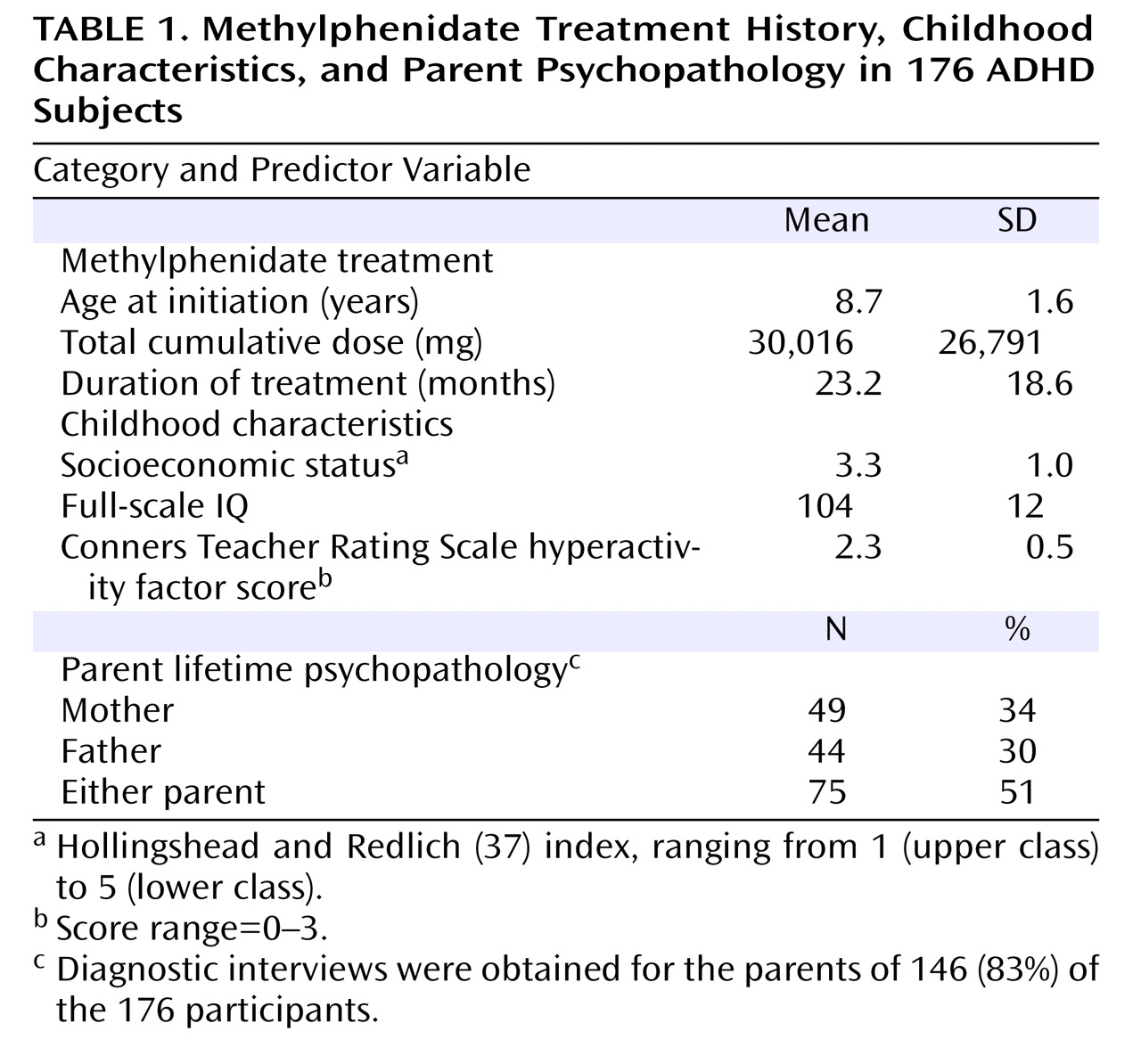

The distribution of the 176 participants by age at initiation of methylphenidate treatment was as follows: 6 years, 25 subjects (14%); 7 years, 49 subjects (28%); 8 years, 29 subjects (16%); 9 years, 28 subjects (16%); 10 years, 23 subjects (13%); 11 years, 19 subjects (11%); and 12 years, 3 subjects (2%). The daily dosage of methylphenidate was 41.7 (SD=12.4) mg. The means for the nine predictor variables are shown in

Table 1 . Participants were middle class, of average intelligence, and had relatively severe ratings of hyperactivity (mean ratings=2.3 [out of possible 3.0]). One-third of the mothers, one-third of the fathers, and one-half of parents in the either parent predictor variable had a lifetime mental disorder.

Outcome Variables

Among the 176 participants treated, 80 (45%) fulfilled criteria for substance use disorder at some time in their lives. Of these, 49 (28%) had alcohol use disorder, and 65 (37%) met criteria for non-alcohol substance use disorder. Forty-three (24%) of those individuals who met criteria for non-alcohol substance use disorder also fulfilled criteria for stimulant use disorder.

Building and Testing the Model

First, univariate analyses were conducted for the nine predictor variables with each of the four outcome variables.

Any substance use disorder

The following two predictor variables had p values less than 0.20: age at initiation of treatment (Wald χ 2 =3.47, p<0.06) and socioeconomic status (Wald χ 2 =2.47, p<0.12).

Alcohol use disorder

Only one predictor variable had a p value less than 0.20: treatment duration (Wald χ 2 =1.75, p<0.19).

Non-alcohol substance use disorder

The following two predictor variables had p values less than 0.20: age at initiation of treatment (Wald χ 2 =4.92, p<0.03) and socioeconomic status (Wald χ 2 =2.86, p<0.09).

Stimulant use disorder

Only one predictor variable had a p value less than 0.20: age at initiation of treatment (Wald χ 2 =3.33, p<0.07).

Since only one predictor variable was associated with alcohol use and stimulant use disorders (p>0.05), no further analyses were conducted for these two outcomes. For any substance use and non-alcohol substance use disorder, the two predictor variables that showed promise, age at initiation and socioeconomic status, were entered together and rerun in the proportional hazards analyses. The only predictor variable that remained significant (p<0.05) was age at initiation of stimulant treatment, only for the non-alcohol substance use disorder outcome (Wald χ 2 =4.24, p<0.04). Participants who developed non-alcohol substance use disorder (N=65) were treated at a significantly later age relative to those who never developed non-alcohol substance use disorder (N=111) (mean=9.10 [SD=1.74] years versus 8.52 [SD=1.55] years, t=2.31, df=174, p=0.02).

We also compared the rates of non-alcohol substance use disorder in probands with rates of the disorder in the 178 non-ADHD comparison subjects. ADHD probands were classified as early- (methylphenidate treatment began at age 6 or 7) and late-treated (methylphenidate treatment began at ages 8 to 12). The division was made at age 8, since this was the sample mean and median. Lifetime rates of substance use disorder were significantly greater among late-treated probands relative to early-treated probands (44% versus 27%; Wald χ 2 =5.38, p<0.02) and non-ADHD comparison subjects (44% versus 29%; Wald χ 2 =6.36, p<0.02), with no difference between the two latter groups (27% versus 29%; Wald χ 2 =0.12, p>0.10).

We also considered that the persistence of ADHD might have accounted for the relationship between age at stimulant initiation and the development of substance use disorder. To examine this possibility, we conducted a survival analysis with age at initiation and age at ADHD offset as predictor variables and non-alcohol substance use disorder as the outcome variable. Results showed that age at stimulant initiation significantly predicted substance use disorder outcome when controlling for the offset of ADHD (Wald χ 2 =3.78, p=0.05), but age at offset of ADHD did not predict the development of substance use disorder when controlling for age at stimulant initiation (Wald χ 2 =2.51, p>0.10). In other words, age of desistance of ADHD was not relevant; only the age at which stimulant treatment was started predicted substance use disorder.

Finally, we examined the specificity of the relationship—i.e., Does age at initiation of methylphenidate treatment predict only substance use disorder or also the development of other disorders? Separate survival analyses were conducted for the following lifetime diagnoses: antisocial personality, mood, and anxiety disorders. Results showed that only antisocial personality disorder was significantly and positively associated with age at stimulant initiation (Wald χ 2 =14.87, p<0.001). Mood (Wald χ 2 =1.35, p>0.10) and anxiety disorders (Wald χ 2 =0.40, p>0.10) were not associated with age at stimulant initiation.

Post Hoc Analyses of Antisocial Personality Disorder and Substance Use Disorder

It is not surprising that age at initiation was significantly associated with both substance use disorder and antisocial personality disorder, since follow-ups of our sample consistently showed substantial comorbidity between substance use disorder and antisocial personality disorder

(3 –

6) . This finding raised the possibility that antisocial personality disorder accounted for the substance use disorder treatment initiation relationship. Therefore, the following two additional survival analyses were conducted: 1) one with antisocial personality disorder as the outcome and non-alcohol substance use disorder as the covariate and 2) the other with substance use disorder as the outcome and antisocial personality disorder as the covariate. The first analysis showed that age at first methylphenidate treatment remained significantly associated with antisocial personality disorder when substance use disorder was covaried (Wald χ

2 =7.67, p<0.01). However, when we controlled for antisocial personality disorder, the relationship between treatment initiation and substance use disorder was no longer present (Wald χ

2 =0.09, p=0.76).

This finding raised the possibility that children who were referred relatively later for treatment had higher levels of conduct problems relative to children who were referred earlier. If this was indeed the case, conduct problems in childhood could have accounted for higher subsequent rates of both antisocial personality disorder and substance use disorder, and age at methylphenidate initiation would have been irrelevant to later substance use disorder. Such a possibility seems viable, since even in our sample with very low conduct problems, we found that the severity of such problems predicted later antisocial personality disorder

(39) . However, there was no relationship, not even a tendency, between age at first methylphenidate treatment and the severity of conduct problems (measured by teacher ratings) (r=0.05, df=176, p=0.49).

A second possibility was that parents with antisocial personality disorder or substance use disorder were relatively less diligent about bringing their child in for treatment, perhaps accounting for the apparent relationship between age at first stimulant treatment and the later development of substance use and antisocial personality disorders in the child. This possibility was examined in three ways. First, age at first methylphenidate treatment was compared for offspring of parents with and without these disorders. The mean of stimulant initiation was 8.3 (SD=1.6) years for offspring of parents with antisocial personality disorder versus 8.7 (SD=1.6) years for offspring of parents without antisocial personality disorder (t=0.61, p=0.54). The mean of stimulant initiation was 8.5 (SD=1.0) years for offspring of parents with substance use disorder versus 8.8 (SD=1.6) years for offspring of parents without substance use disorder (t=0.75, p=0.45). The mean of stimulant initiation was 8.5 (SD=1.7) years for offspring of parents with antisocial personality or substance use disorder versus 8.8 (SD=1.6) years for offspring of parents without antisocial personality or substance use disorder (t=0.75, p=0.45). Point biserial correlations for age (years) at first methylphenidate treatment with the presence or absence of mental disorder were as follows: 1) parent antisocial personality disorder: r=–0.05, df=176, p=0.54; 2) parent substance use disorder: r=–0.06, df=176, p=0.45; and 3) parent antisocial personality or substance use disorder: r=–0.06, df=176, p=0.45. Last, we compared early- and late-treated subjects on the rates of antisocial personality and substance use disorders in parents (antisocial personality disorder: 3% [early treated] versus 5% [late treated], p=0.37; substance use disorder: 25% [early treated] versus 18% [late treated], p=0.69; antisocial personality disorder or substance use disorder: 25% [early treated] versus 18% [late treated], p=0.69). In summary, we found no relationship between antisocial personality or substance use disorder in parents and age at initiation of stimulant treatment.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective follow-up study to examine the relationship between age of initiation of methylphenidate treatment for ADHD and the subsequent development of substance use disorder, as well as other disorders. The risk of developing substance use disorder was significantly associated with age at methylphenidate treatment; specifically, the later the treatment, the greater the chances of developing substance use disorder. The principal value of this finding is that it challenges the position that early exposure to stimulants presents particular risk to children with ADHD, at least with regard to substance use and antisocial personality disorders.

Unexpectedly, the development of antisocial personality disorder accounted for the association between age at first treatment with methylphenidate and substance abuse. This association was not the result of age-related differences in early conduct problems. Although these findings are consistent with animal data suggesting that later preference for cocaine in rats is relatively decreased by exposure to methylphenidate in early rather than late development

(16,

17), the relevance of animal neurodevelopmental models of stimulant exposure is not straightforward. The relationship between age at first stimulant exposure and later substance use disorder must account for the observation that the relationship is mediated by the development of antisocial personality disorder.

It is unclear why age at initiation of stimulant treatment and the later development of substance use and antisocial personality disorders appear to be related. Castellanos et al.

(40) reported that unmedicated children with ADHD had smaller brain white matter volume relative to medicated children with ADHD and non-ADHD comparison subjects. Early stimulant treatment might increase brain functional reserve by increasing (or normalizing) brain white matter volume during a developmental period of greatest plasticity, and greater brain functional reserve may be associated with decreased risk of substance use disorder. We are presently conducting an adult follow-up study on the current sample, now age 40, in which magnetic resonance imaging scans will examine whether there are structural differences in early- and late-treated subjects.

The major limitation of the present study is that it is an experiment of nature that relied on a referred clinical sample. The age at referral was not experimentally controlled, and thus unidentified, nonrandom factors related to treatment initiation, other than those assessed, may have contributed to the relationship between age at first treatment and substance use and antisocial personality disorders. For example, parental family factors may have mediated this association, which could have resulted in a failure to attend to the needs of the child that led parents to delay treatment for their children. Parent psychopathology, in general, and parent antisocial personality and substance use disorders, in particular, do not explain this relationship, but other features related to child rearing may be relevant. Therefore, replication is essential. Other limitations include the ethnic homogeneity of our sample, exclusion of female children, and the minimum age of 6, thus restricting generalizability of results to clinic-referred 6- to 12-year-old Caucasian males. Furthermore, we do not know whether our findings apply to early stimulant exposure or to early referral for treatment, independent of methylphenidate administration. It could be that timing of interventions, regardless of their nature, affect long-term outcome. Thus, the duration of untreated ADHD in childhood, rather than stimulant treatment per se, might be the important variable. In other words, we cannot differentiate presumed effects of stimulant medication from effects of age at referral, independent of stimulant exposure.

The use of stimulants in young children has generated considerable controversy. At the least, the findings of the present study do not indicate that treatment relatively early in childhood increases risk for negative outcomes.