This report updates national estimates of annual lost earnings associated with mental disorders in the United States. The first such estimate, a loss of $44.1 billion in 1985, was made by Rice et al.

(1) in a report commissioned by the U.S. Public Health Service, which used data from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study

(2) . This estimate was subsequently updated to a loss of $77 billion in 1992 by Harwood et al.

(3) in a report commissioned by NIMH that used data from the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS)

(4) . The current update is based on data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R)

(5) .

Similar to Rice et al. and Harwood et al., we used regression analysis to predict personal income in the 12 months before interview from information about 12-month and lifetime DSM-IV mental disorders, while controlling for sociodemographic variables and substance use disorders. However, we improved on the earlier analyses in four ways. First, the NCS-R assessed a wider range of disorders than the ECA or NCS. Second, the NCS-R measured personal earnings, whereas the earlier surveys measured the broader category of personal income (which included unearned income). Exclusion of unearned income removes a bias that was present in the earlier studies. Third, NCS-R estimates are more generalizable than earlier estimates because the NCS-R is a nationally representative survey of respondents ages 18–64, whereas the ECA was a local survey and the NCS was restricted to ages 18–54. Fourth, the statistical analysis we used improves on the approaches used in the earlier studies.

Results

Sociodemographic Variable Distributions

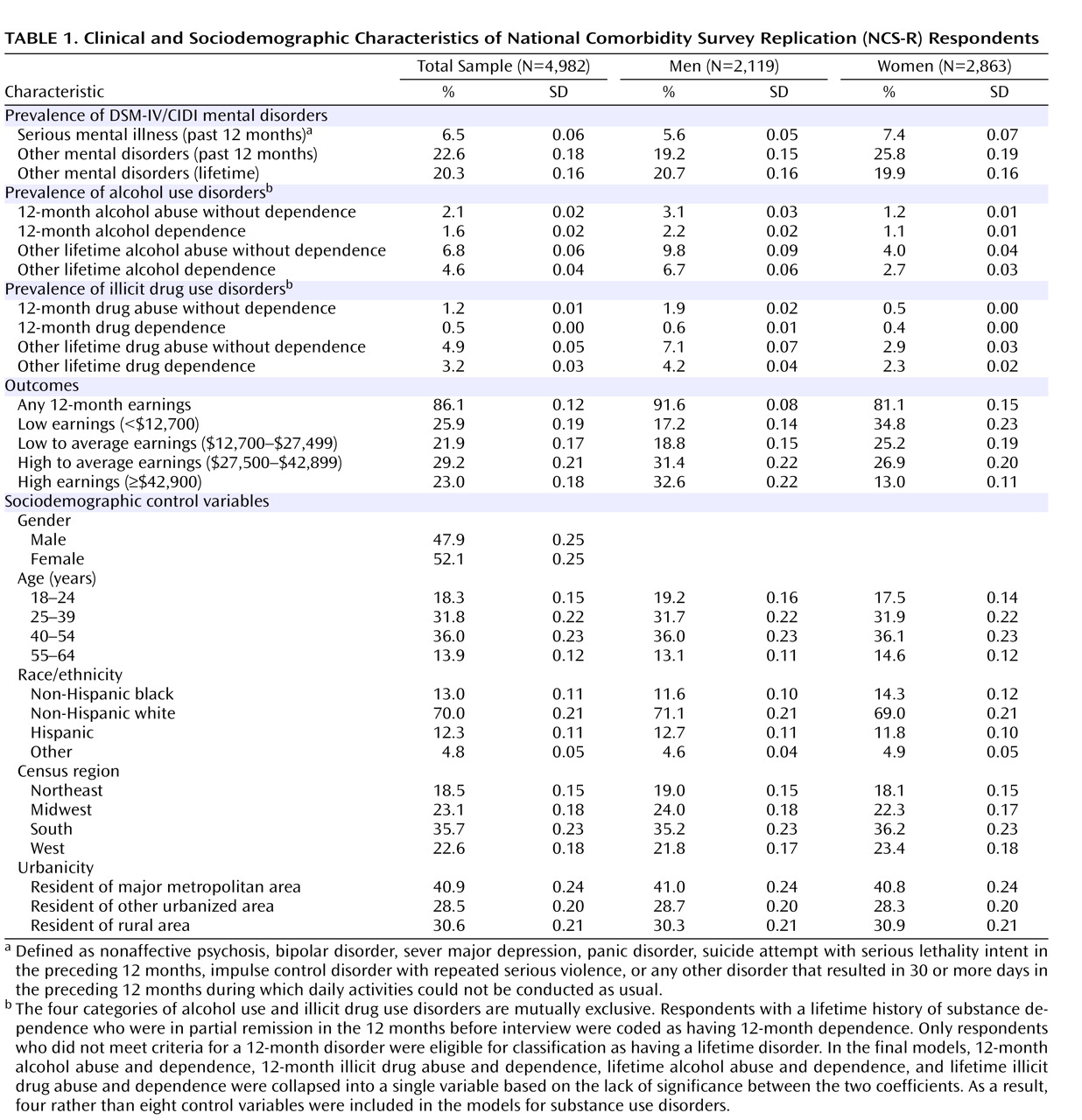

The prevalence estimates of DSM-IV mental disorders were 6.5% for 12-month serious mental illness, 22.6% for other 12-month mental disorders, and 20.3% for other lifetime mental disorders (

Table 1 ). It was significantly more common for women than men to report a serious mental illness (t=2.6, df=4,980, p=0.008) or other 12-month mental disorder (t=4.7, df=4,980, p<0.001), but there was no significant gender difference in other lifetime disorders (t=0.5, df=4,980, p=0.59). Most respondents (86.1%) reported some personal earnings in the 12 months before interview, although more male than female respondents reported personal earnings (91.6% versus 81.1%; t=6.4, df=4,980, p<0.001). Among those respondents with any earnings, men had significantly higher earnings distribution than women (χ

2 =63.6, df=3,126, p<0.001). Weighted sample distributions for sociodemographic control variables were consistent with census population distributions by construction

(6) . Substance use disorder distributions were consistent with those reported previously for the total NCS-R sample

(12,

27) .

Model Fitting

Seven one-part models and seven two-part models were estimated and compared. Each model included the same predictors: 12-month serious mental illness, other 12-month mental disorders, other lifetime mental disorders, controls for sociodemographic variables (age, gender, race/ethnicity, census region, and urbanicity), controls for substance use disorders, and interactions between gender and all other model variables to predict past year earnings. All differences among models involved assumed functional forms and error structures. The seven one-part models, each of which was estimated in the total sample (i.e., included respondents with no earnings), included an ordinary least squares regression model, which assumed linear associations between the predictors and the outcome with an independent error structure, and six generalized linear models. The generalized linear models assumed one of two nonlinear functional forms for the association between predictors and outcome (square root or logarithmic) and one of three error structures (independent, error variance proportional to the predicted value, or error variance proportional to the square of the predicted value). The seven two-part models used logistic regression in part 1 to predict any earnings versus no earnings and the same set of seven models in part 2 to predict amount earned among those respondents with any earnings.

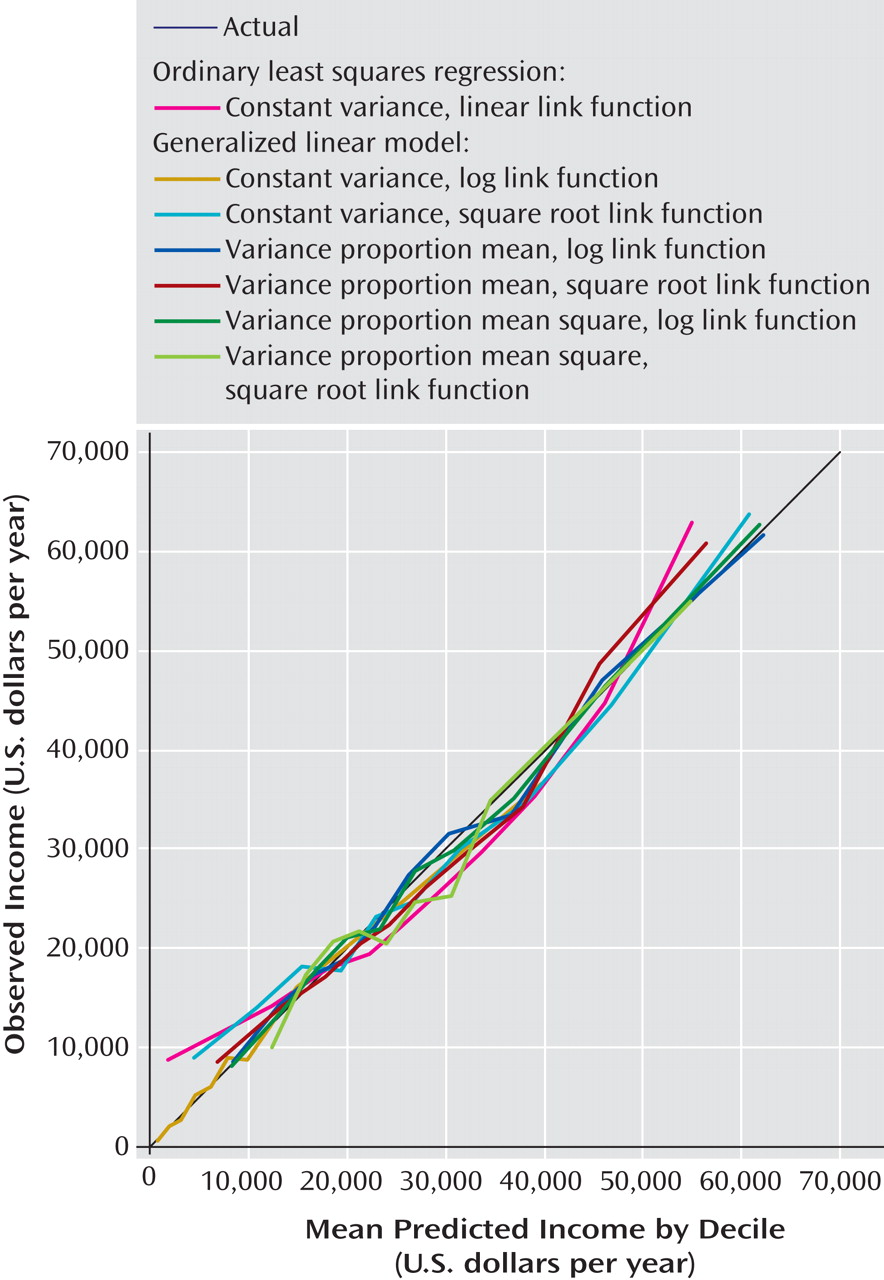

Accuracy of models was evaluated by plotting the associations between predicted mean earnings and observed mean earnings for deciles of predicted earnings (

Figure 1 ). Only the one-part model plots are presented because they were clearly better than those for the two-part models (results for the two-part models are available on request). The actual decile means form a 45° line in the figure; points above or below this line indicate either overestimation or underestimation. The figure shows that the ordinary least squares regression model did noticeably worse than the generalized linear models, as ordinary least squares regression overestimated at both the ends of the distribution and underestimated in the middle. Several generalized linear models had predicted means that fell very close to the observed means throughout the range. The best-fitting of these models, in terms of mean squared error, assumed a logarithmic association between the predictors and the outcome and error variance proportional to the predicted value of the outcome. A number of other model-fitting tests proposed in the econometrics literature

(28) also showed this to be the best-fitting model (results available on request).

Individual-Level Predictive Effects of Mental Disorders on Earnings

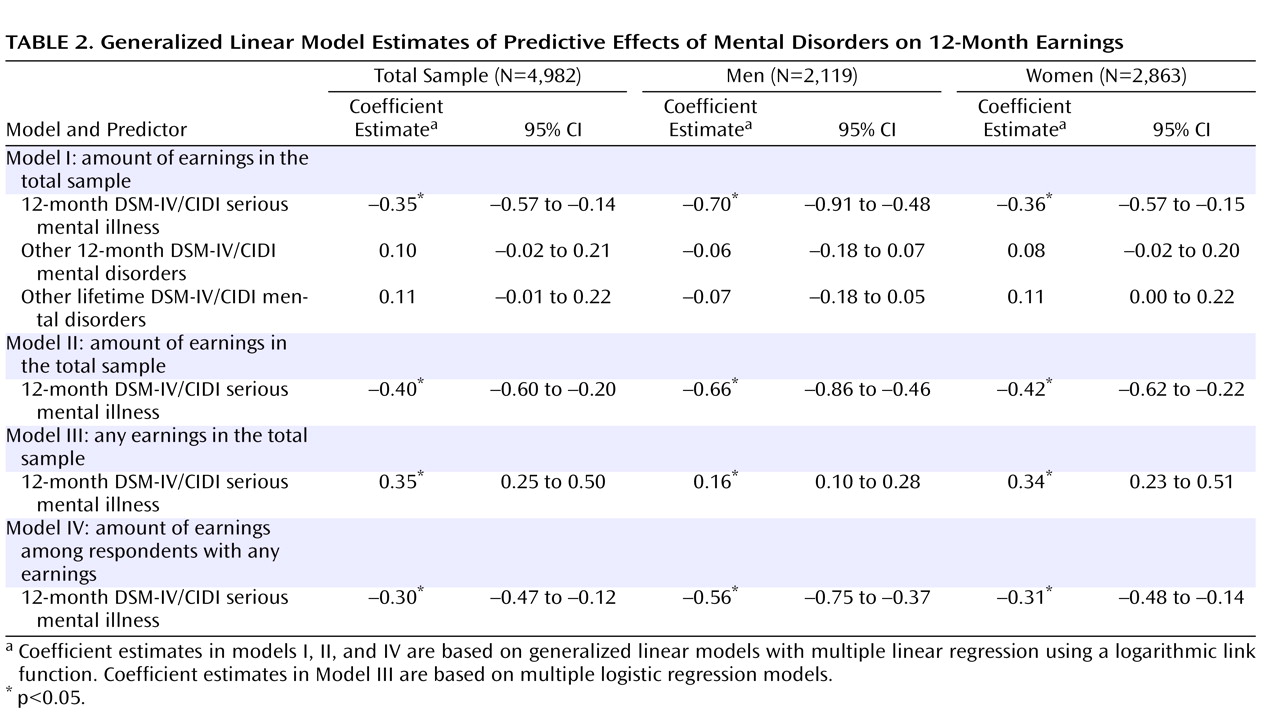

We used the best-fitting generalized linear model specification to compare predictive effects of serious mental illness, other 12-month DSM-IV/CIDI mental disorders, and other lifetime mental disorders on 12-month earnings (

Table 2 ). The first model shows that serious mental illness was significantly associated with reduced earnings among both men and women, while associations with other 12-month and lifetime mental disorders were not statistically significant. Attempts to decompose the measures of other 12-month and lifetime mental disorders failed to find any specification in which subsets of these disorders were significant. A revised model (model II) retained serious mental illness but eliminated other mental disorders as predictors. Serious mental illness was again significant and again had negative effects in model II.

Considering model II as the preferred model, we next evaluated whether the predictive effect of serious mental illness on earnings varied significantly depending on substance use disorders by estimating a model that included interaction terms between serious mental illness and substance use disorders. These interactions were not statistically significant either in the total sample (F=0.3, df=4, 4,941, p=0.90) or separately among men (F=0.3, df=4, 4,937, p=0.90) or women (F=0.4, df=4, 4,937, p=0.70). Additive controls for substance use disorders were consequently included in the final model. The effect of serious mental illness in model II was then disaggregated by estimating separate models to predict having any earnings versus no earnings (model III) and to predict amount earned among those respondents with any earnings (model IV). Both effects were significant among both men and women. Serious mental illness was associated with significantly reduced odds of having any earnings and, among those with any earnings, significantly lower earnings than those of respondents without serious mental illness.

Simulated Individual-Level Effect Estimates

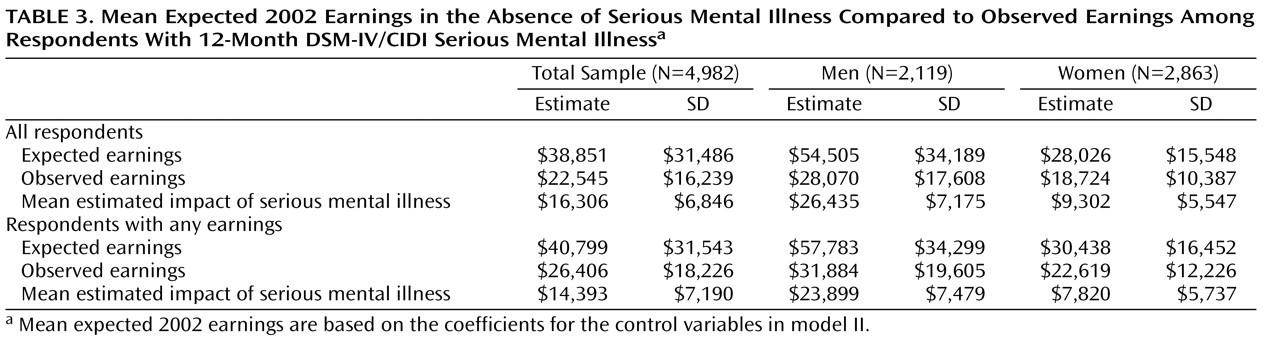

Simulated mean

expected annual earnings of respondents with serious mental illness in the absence of that serious mental illness was estimated at $38,851, compared with mean

observed earnings of $22,545 (

Table 3 ). The difference, $16,306, is the estimated mean impact of serious mental illness on earnings. This estimate is higher among men ($26,435) than women ($9,302). The simulation was repeated in the subsample of respondents with any earnings, where the adverse effect of serious mental illness was estimated to be lower than in the total sample ($14,393 versus $16,306). The same held true both among men ($23,899 versus $26,435) and among women ($7,820 versus $9,302). This difference in mean effects between the total sample and subsample reflects the fact that serious mental illness is associated not only with lower earnings among persons who have any earnings but also with decreased odds of having any earnings at all.

Decomposition of Individual-Level Effect Estimates

When projected to the total sample, the lower earnings of respondents with serious mental illness and any 12-month earnings were 75.4% (SD=9.0) of the overall decrement in earning associated with serious mental illness. This means that the remaining 24.6% was due to the lower probability of persons with serious mental illness having any earnings (in conjunction with the fact that if they had had any earnings, they would have earned significantly less, on average, than persons without serious mental illness who were otherwise identical to them in the control variables). The proportion of the total estimated effect of serious mental illness due to lower earnings among those with any earnings was higher among men (79.6% [SD=8.2]) than women (69.6% [SD=12.2]).

Simulated Societal-Level Effect Estimates

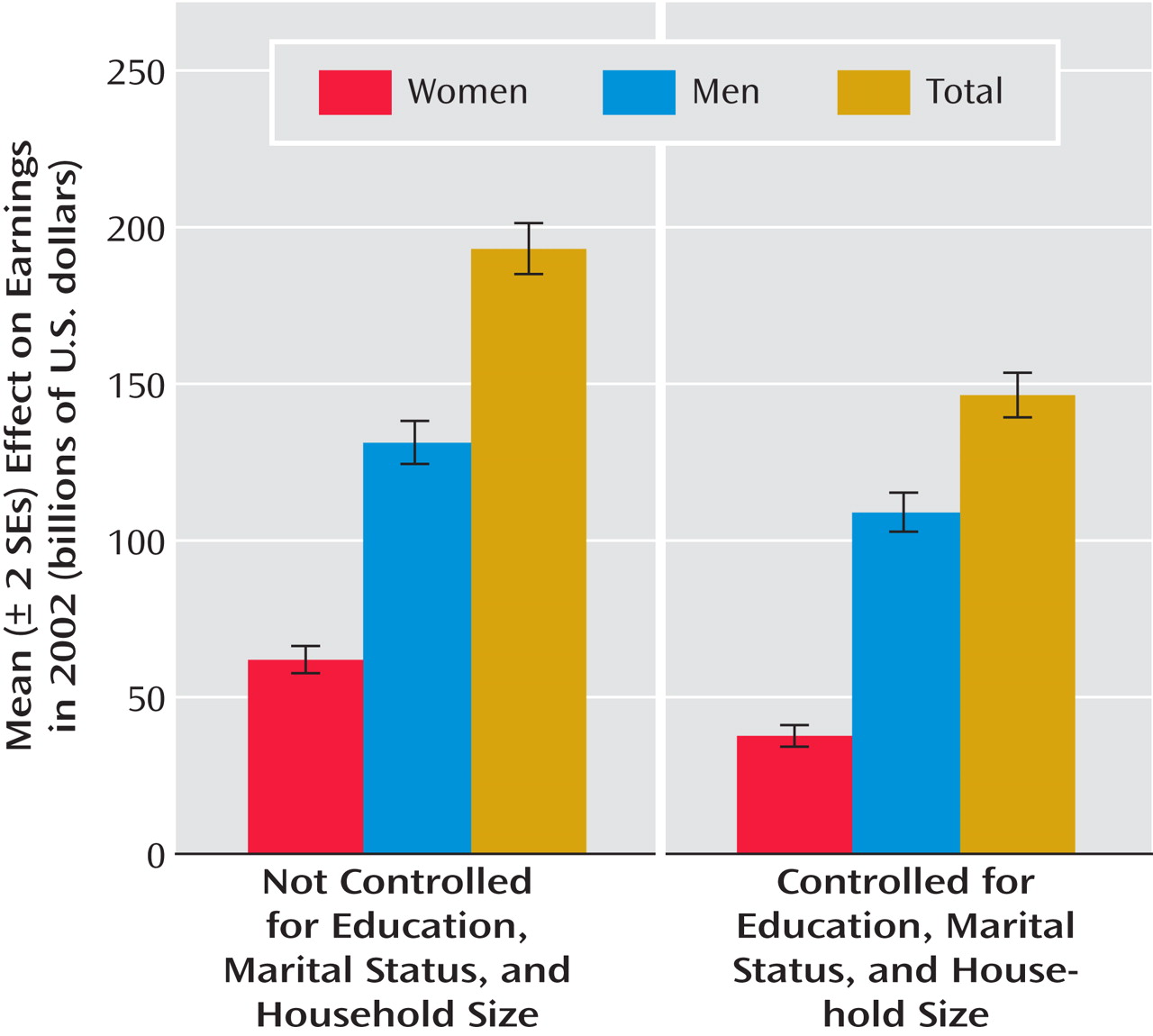

The societal-level effect of serious mental illness was estimated by projecting the individual-level effect to the 179.6 million persons ages 18–64 in the noninstitutionalized civilian population of the United States

(29), taking into consideration the estimated prevalence of serious mental illness and the estimated individual-level effect of serious mental illness on earnings (

Figure 2 ). The estimated societal-level effect was $193.2 billion (SD=55.5) in the total population, $131.3 billion (SD=32.4) among men, and $61.9 billion (SD=19.7) among women.

Sensitivity Analysis

We replicated the simulation using three other models shown to be close to the best-fitting model in reproducing the observed population income distribution: one model with a logarithmic transformation of the outcome and error variance proportional to the square of the predicted value of the outcome and two models that used a square root transformation of the outcome with error variance assumed to be either proportional to the predicted value or proportional to its square (

Figure 1 ). The estimated effect sizes ranged across these models from a low of $178.1 billion (SD=49.3), which was 8% lower than in the best-fitting model, to a high of $213.9 billion (SD=66.6), which was 11% higher than in the best-fitting model. Roughly comparable ranges were found for estimates among men ($124.3–$152.2 billion or between 5% lower and 16% higher than in the best-fitting model) and women ($56.5–$65.1 billion or between 9% lower and 5% higher than in the best-fitting model).

We investigated the extent to which the estimated societal-level effect of serious mental illness could be explained by control variables included in earlier studies but omitted from our models: education, marital status, and household size (

Figure 2 ). The estimated total-population effect of serious mental illness on earnings decreased by approximately 25%, from $193.2 billion (SD=55.5) to $144 billion (SD=48.1). The magnitude of this decrease, however, was substantially larger among women (39%) than men (17%), with the estimate decreasing from $61.9 billion (SD=19.7) to $37.8 billion (SD=16.6) for women and from $131.3 billion (SD=32.4) to $109 billion (SD=29.2) for men.

Discussion

Serious mental illness was estimated to be associated with a loss of $193.2 billion in personal earnings in the total U.S. population in 2002. To put this cost in perspective, it is larger than the $145 billion economic stimulus package recently proposed by President Bush in January 2008 to help avoid an economic recession in the United States. Our estimate is, on the surface, much higher than the estimates reported by Rice et al. or Harwood et al. These differences can be easily explained, though, by two factors: 1) inflation (i.e., adjusting earlier estimates to 2002 dollars) and 2) controlling for education, marital status, and household size. Adjusting earlier estimates into 2002 dollars using cost compensation trend data from the U.S. Department of Labor (available at www.bls.gov/ncs/ect/home.htm) changes the Rice et al. estimate to $83.1 billion and the Harwood et al. estimate to $107.7 billion. The Rice et al. estimate becomes higher still when we adjust for the fact that they did not include fringe benefits for paid sick leave or health insurance. Furthermore, when Harwood et al. estimated a revised model version that deleted education, marital status, and household size as control variables, the estimated effect of mental disorders increased by a factor of 2.26, making it even larger than our estimate when adjusted to 2002 dollars ($241 billion).

Irrespective of the reasons for the differences in estimates across studies, all three studies found that mental disorders are associated with massive losses of productive human capital. This finding adds to a growing body of evidence that the impaired functioning associated with mental disorders carries an enormous societal burden

(30,

31), although caution is needed in inferring causation from our associational results. Comparative cost-of-illness studies show that the magnitude of this association is high in relation to most physical disorders. For example, a recent U.S. study found that up to one-third of illness-related days in which subjects could not carry out daily activities as usual are related to mental rather than physical disorders

(31) . Yet only 6.2% of all U.S. health care spending is devoted to treatment of mental disorders

(32), even though most persons with mental disorders do not get treatment

(33) and treatment is much higher for physical than mental disorders with comparable levels of impairment

(30) . This kind of comparative information about burden and treatment should be integrated with information about comparative treatment effectiveness to help guide decisions about implementation of disorder-specific screening and treatment programs and about federal health care research resource allocation

(34) .

Our results go beyond those of earlier studies in decomposing the association between serious mental illness and low earnings into components based on having no earnings at all and, among those with any earnings, having low earnings. We found that three-fourths of the total association between serious mental illness and earnings in the NCS-R is due to lower earnings among employed persons with versus without serious mental illness, while the remaining one-fourth is due to a lower probability of having any earnings at all among persons with versus without serious mental illness. The dominant influence of low earnings among those persons with any earnings at all raises the possibility that appropriate policy solutions might include increased job training and vocational rehabilitation for workers with serious mental illness and increased enforcement of the Americans With Disabilities Act with regard to corporate practices of promotion and remuneration. More detailed analyses of the data are needed, however, to understand the occupational career dynamics associated with the effects of serious mental illness on earnings among employed persons before the relevance of these and other policy implications will become clear. Further analysis is also needed to understand the determinants of the comparatively high unemployment rate among persons with serious mental illness. Although such analyses go well beyond the scope of the current report, these analyses need to be the focus of future studies in order to further consider all the policy implications related to the association between serious mental illness and earnings documented here.

This study has a number of limitations, including that 1) mental disorders were assessed with fully structured lay interviews rather than clinical interviews, 2) earnings were assessed with self-report rather than administrative records, and 3) the dynamic association was estimated with cross-sectional data. Another limitation is that the productive labor of women in domestic activities was not assigned a monetary value in the analysis even though it has value. As a result of this, the true financial impact of the fact that women with serious mental illness are less likely than other women to have earnings was overestimated to the extent that the unpaid labor of women without earnings is greater than that of women with earnings.

One technical limitation is that we applied a flat fringe benefit rate of 42% to all workers. It could be argued that the average fringe benefit rate of workers with serious mental illness is lower than the national average because the lower-paying jobs of persons with serious mental illness probably also have lower than average fringe benefit rates. We were unable to assign differentiated fringe benefits to individual NCS-R respondents because no nationally representative administrative data exists that would allow us to do this. It should be noted, however, that the assumption of constant fringe benefits leads to a conservative bias in our estimates, due to the fact that we presumably overestimated total compensation to workers with serious mental illness.

Perhaps the most significant limitation of the analysis is that we were unable to adjust for the reciprocal effect of low earnings on risk of mental disorder. There is good reason to believe that such an effect exists

(35) . Because of this limitation, while we can state that serious mental illness is

associated with low earnings, we cannot state how much of this association is due to serious mental illness

causing low earnings. Earlier studies and, indeed, virtually all cost-of-illness studies

(36) have the same limitation. There is no way to correct this limitation definitively with nonexperimental data. Controlling for mediating variables, such as education and marital status, which might themselves be reciprocally related to mental disorder, would not be a corrective measure, as this can lead to overcorrection. Longitudinal analysis can sometimes help. For example, a 5-year longitudinal follow-up in four U.S. cities of 5,000 initially employed respondents ages 18–30 from the CARDIA study found that high baseline Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) scores significantly predicted subsequent unemployment and decreases in income even after controlling for baseline education, marital status, and history of prior unemployment

(37) . Even here, though, high baseline CES-D scores could have been influenced by knowledge of job insecurity, which in turn predicted subsequent job loss. Sophisticated econometric models can sometimes be useful in resolving such uncertainty if information is available on third variables that influence one but not the other variable in a reciprocal pair

(38), but such models are highly sensitive to misspecification

(39) .

Although not a limitation per se, it is also worth noting that we purposely restricted the analysis to only one component of the societal costs of mental disorders: the impact on earnings. We did not consider such other societal costs as the impact of mental illness on welfare and Supplemental Security Income or the workplace effects of mental illness on lost productivity. The results reported here should consequently not be considered a comprehensive estimate of all the societal costs of mental illness, but only the estimate of one component of these costs, with the caveat that the $193.2 billion decrement in earnings should be seen as associated with mental illness rather than necessarily caused by mental illness.

Experimental interventions are ultimately the only reliable way to resolve this uncertainty and document causal effects of mental disorders on earnings or other indicators of role performance

(40) . Such interventions are comparatively rare and almost always include only relatively short-term follow-up. It is consequently important for future treatment effectiveness studies to include measures of functioning (such as measures of employment status, work productivity, and earnings) as secondary outcomes and for these studies to follow participants as long as possible in order to document long-term effects of mental disorders on functional outcomes. It is also important to note that some interventions, such as those based on a social skills training model or an occupational rehabilitation model, might be effective in decreasing unemployment and improving job performance among people with serious mental illness without decreasing symptoms of mental illness. It is important that interventions of this type, aimed directly at addressing the problem of low earnings, be implemented and evaluated. Controlled studies of these sorts, when combined with information about the prevalence and course of illness from epidemiological studies, are our greatest hope of obtaining more definitive data than presented here about the effects of mental disorders on earnings and other aspects of functioning.