Scientific advances have fueled both gains in health care outcomes and growth in health care costs

(1) . Health care for mental illness is no exception, with significant improvements in the treatment of schizophrenia, depression, and other common disorders during the last 20 years. As a general rule, diffusion and implementation of research-based health care proceeds slowly

(2) . Rates of dissemination and adoption of new treatments are influenced by many factors other than patient needs and scientific evidence. For example, marketing, profit motives, health care cultures, professional and guild issues, spending levels, organizational structures, financing mechanisms, and implementation difficulties all have been shown to influence diffusion

(3) . Because these factors exhibit great diversity across states, regions, and local agencies, it is perhaps not surprising that health care exhibits a high degree of geographic variation

(4) .

Yet the gap between evidence-based practices and usual services is enormous in mental health

(5 –

8) . For example, the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team found that less than 30% of schizophrenia outpatients receiving care in two large public mental health systems were prescribed an antipsychotic medication within the recommended dose range and even smaller percentages received evidence-based psychosocial treatments

(9) . The National Comorbidity Study Replication showed that less than half of persons with mental disorders received any treatment in the past 12 months, only one-third of treatments met minimal standards of adequacy, and those in rural areas as well as racial and ethnic minorities and elders were less likely to receive any treatment

(7) .

Mental health services are similar to general health care services in many ways, particularly for treatments combining medications with a variety of related office visits. Mental health services differ, however, in the relative importance of psychosocial treatments, such as psychotherapy and psychiatric rehabilitation. Unlike new medications, in which implementation of new practices is supported and encouraged by marketing efforts, psychosocial treatments rarely are encouraged by commercial marketing. As is the case with medications that have gone “off patent” and are available in generic form, there is little economic incentive to market psychosocial services since they are not under patent protection.

In this article, we explore the importance of diffusion and the variation in adoption of high- and low-value treatment strategies in health care, with a focus on three factors that influence diffusion: informational or attitudinal barriers, funding mechanisms, and profitability. We conclude with several proposals designed to better understand and improve the diffusion of evidence-based treatments for mental illness.

Determinants of Diffusion and Adoption

The earliest studies of diffusion arose in agriculture, where researchers puzzled as to why new technological improvements in farming, such as hybrid corn, were so slow to be adopted by farmers

(10) . This was viewed by rural sociologists as evidence of seemingly irrational resistance to change that might be mediated by education and past experiences with adopting new products

(3) . By contrast, economists such as Griliches

(10) stressed the importance of the profit motive: farmers in Iowa, who innovated early, made more money from adopting hybrid corn than the late adopters in Arkansas. Thus, a long-standing tension in the literature exists between the economic models that stress rational models of nonadoption and the sociological models where the inability to adopt a new technology reflects the difficulty of changing behavior from the old habits to something new

(11) .

While the economics literature has largely ignored issues of collective decision-making, other studies have focused on the organizational barriers facing not-for-profit institutions seeking to adopt cost-saving or efficiency-enhancing innovations

(12,

13) . We selected three general factors from the literature to explain the speed of diffusion. The first, favored by sociologists, is informational or attitudinal barriers; either potential adopters either do not know about the innovation’s benefits or they know that the innovation is useful but still fail to adopt. Two examples are considered: beta-blockers and naltrexone. We consider the contributing effect of a lack of marketing for each medication.

The second relates to financial and resource constraints on government funding. Our examples are multisystemic therapy (MST) and the IMPACT model for geriatric depression. The final category is the profitability of the treatment, where economic incentives can exert an independent influence on the speed of diffusion. Here, we consider the rapid diffusion of second-generation antipsychotics due to aggressive marketing. These factors are not mutually exclusive, and when all three are aligned—informational and resource barriers are low and profitability is high—new innovations with real clinical benefits diffuse in months rather than in years, as in the case of tetracycline in the 1950s

(14) . These factors are not meant to be exhaustive; Essock et al.

(15), for example, have identified a variety of other barriers in not-for-profit institutions such as skepticism about scientific methods or issues of professional or consumer authority in vying for control.

Informational and Attitudinal Barriers

Berwick

(2) and others have called attention to the remarkably slow rate of diffusion for beta-blockers in the treatment of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Despite strong clinical evidence of effectiveness by 1985

(16), the median use (at the state level) of beta-blockers was still just 68% in 2000/2001

(17) . Why was diffusion so slow? Bradley et al.

(18) found no single cause, but instead a variety of causes reflecting the professional opinions of the physicians, professional disagreement about the value of beta-blockage, or the lack of administrator or opinion leaders’ support. The rapid growth in the use of beta-blockers since the 1990s has occurred largely because of its adoption as a publicly available quality measure.

Naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism is another example in which informational barriers matter. As of 2006, there were 29 published randomized, placebo-controlled trials of naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism

(19) . Various studies show reductions in the mean number of drinking days per week, the amount of alcohol consumed per drinking occasion, the risk of relapse to heavy drinking, and the severity of craving for alcohol.

Nevertheless, few patients in alcoholism treatment receive naltrexone, and the proportion may even be declining over time

(20) . In 1992, epidemiologic data indicated that approximately 13.7 million adults in the U.S. met criteria for alcoholism

(21), and in 2000, some 1.3 million Americans received treatment for alcoholism in medical care settings

(22) . Yet only about 3%–13% of those in treatment received naltrexone

(23) . Again, why the slow diffusion?

Mark et al.

(23) found that both patients and physicians cited lack of information about the medication as the primary reason for low use—in the absence of a strong incentive to market medications that are available in generic preparations. Other reasons cited for low use included unfounded fears of addictive potential, confusion about indications, and limited patient demand and access to physicians. Also, within the “culture of abstinence” in the field of substance abuse treatment, some providers object to the use of any medications.

Financial Barriers

Multisystemic therapy (MST) is an intensive, in-home, family-based intervention for youths with severe antisocial and other clinical problems

(24) . It was first developed and tested around 1990 and, with the help of a university-licensed technology transfer organization, has subsequently spread to 32 states and 10 countries

(25) . The research evidence on MST shows that it consistently reduces out-of-home placements, antisocial behavior, and other clinical problems

(26,

27) .

MST has spread faster and more extensively than any other evidence-based child intervention, currently to about 16,000 families a year. Nevertheless, adoption is small in relation to need, and many systems have decided not to adopt MST, with the major barriers the cost of training and financing the intervention (Medicaid reimbursement is often unavailable). Although MST has been associated with cost offsets (cost reductions along other dimensions), the responsibility for children with multiple problems is usually spread across multiple agencies and systems; hence the incentive is for agencies to shift the child to someone else’s budget. In fact, MST is more often funded by the juvenile justice system than by mental health agencies.

As well, there are other barriers; MST requires a relatively high degree of training, supervision, and continuity of workforce. Thus, start-up expenses are high, and skill requirements are at odds with those of the existing workforce. To enhance fidelity, MST implementation is controlled by the founders, which both encourages fidelity and hinders speed of adaptation to local circumstances and spread.

Another example is the IMPACT model for geriatric depression, which includes systematic diagnosis and outcome monitoring, stepped care based on an evidence-based algorithm, disease management with the help of a care manager, and shared decision-making in relation to psychosocial and pharmacological interventions

(28) . The research on IMPACT is quite strong in terms of clinical outcomes

(29), cost-effectiveness

(30), and usability in a large system of managed care

(31) . In many ways, IMPACT provides a model for evidence-based practice development, moving rapidly from efficacy to effectiveness to real-world implementation studies. Nonetheless, diffusion has thus far proceeded slowly with little uptake in most parts of the country and wide regional variation (http://impact-uw.org). As Unützer and colleagues

(32) point out, IMPACT has been implemented only in a few specific areas and often because of serendipitous opportunities, such as unexpected funding generated by Proposition 63 in California

(33) .

Profitability

It is perhaps not surprising that financial reimbursements and marketing should play a role in diffusion. As we pointed out in our introduction, only new medications under patent are especially profitable to market, so often there is limited information available to support dissemination and adoption of other types of treatment. In this section we consider one example: the rapid diffusion of second-generation antipsychotic medications. Standard treatment for schizophrenia includes antipsychotic medications as well as psychosocial interventions and ancillary services

(34,

35) . Since the 1950s, antipsychotic medications have been demonstrated to be effective in treating episodes of psychosis in schizophrenia and other disorders and in preventing additional episodes of psychosis. During the 1990s, a series of “atypical” antipsychotics (also called second-generation antipsychotics) were approved for use in the U.S., and each one was introduced with the promise of greater efficacy and fewer side effects than “typical” (first-generation) antipsychotics. Prices for these new medications were over 10 times the price of customary treatments, but the pharmaceutical industry flooded practicing psychiatrists and the public with advertising, and advocates demanded access to (i.e., insurance payments for) the new medications. Early studies, largely funded by the pharmaceutical industry, indicated that the new “atypical” antipsychotics were remarkably effective

(36) . As a consequence, expenditures for these second-generation medications in the U.S. rose steadily to $11.5 billion in 2006

(37) .

Government agencies agreed to pay for second-generation antipsychotics despite the lack of unbiased comparative evidence

(38) . Because of constraints on mental health funding from Medicaid and state general funds, one unintended consequence of increased spending on new medications was that evidence-based and already poorly funded services, such as housing, vocational, and case management programs, were diminished

(39) . Of importance, all of these changes occurred before well-designed trials compared the second-generation antipsychotics to the first-generation medications.

By 2007, in the minds of many investigators and policy analysts, the evidence had become clear that the new second-generation antipsychotic medications (besides clozapine, which is still rarely used) are no more efficacious in well-controlled trials and certainly no more effective in routine use than the older antipsychotics (e.g.,

40,

41) . Moreover, the evidence continues to emerge that the new medications have different, but equally serious, side effects

(42,

43) . In this case, we may conclude that the rapid adoption of the second-generation antipsychotics was hastened by the high degree of profitability of these medications, which helped to promote a belief among patients, families, practitioners, and mental health administrators that these drugs represented “best practice” treatments.

Similar examples can be found for other second-generation pharmaceuticals such as ezetimibe, used in the treatment of hyperlipidemia and a key component of Vytorin. Owing in part to active marketing efforts in the United States, ezetimibe was by 2006 four times more likely to be prescribed for lowering cholesterol in the U.S. compared to Canada

(44) .

Next Steps: Research and Interventions

The examples of diffusion presented above hint at wide geographic variation in adoption, and so it is perhaps not surprising that these differences will be reflected in variations across regions at a point in time.

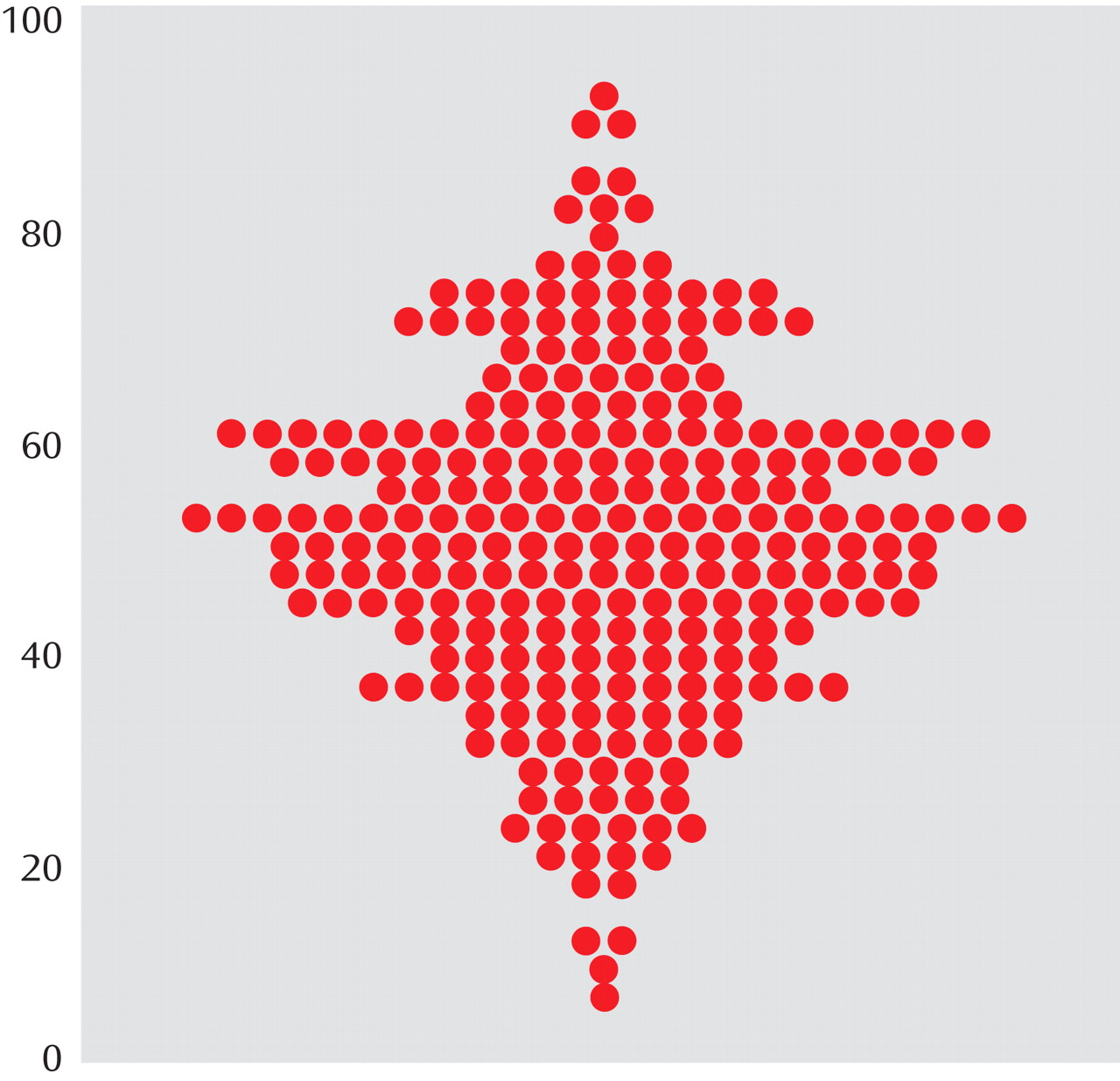

Figure 1, from the Dartmouth Atlas of Cardiovascular Healthcare, shows the distribution of beta-blocker use among Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction by hospital referral region, the basic regional unit of analysis in Dartmouth Atlas studies, in 1994/1995

(45) . Each dot corresponds to a hospital referral region, and the vertical axis shows the percentage of ideal acute myocardial infarction patients treated with beta-blockers at discharge. Note the wide range of adoption, with a few regions using beta-blockers for fewer than 20% of patients, while other regions are using beta-blockers for more than 90% of ideal patients (i.e., those for whom there is no evidence for ruling out the use of beta-blockers). Had beta-blockers diffused rapidly, we would have observed all the regions piled up above 90%—leading to little or no regional variation. Thus, variations at a point in time can be very informative about past regional patterns of diffusion.

For this reason, we suggest that regional variation in the provision of effective mental health care can be a valuable marker in judging the speed of diffusion. Aside from a few studies with sometimes limited data on regional variation

(46 –

50), there is little systematic evidence for how treatment patterns differ across the U.S. in the treatment of mental illness. The evidence is certainly suggestive of large variations; Wang et al.

(46), for example, found that the percentage of patients with serious mental illness who received any mental health treatment ranged from just 27.3% in the Northeast to 43.5% in the West. The study of regional variations is also complicated by differences in the underlying incidence of disease; rates of major depression varied across states from 6.7% to 10.1%

(51) .

A first step would be to use a national database to develop population-based measures of resource utilization and drug treatments stratified by disease type. Examples of such databases include those maintained by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

(50), the Medicare data under the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program, or state-level Medicaid data. As noted above, the challenges to creating comparable measures across regions are to develop a comprehensive sample of those with mental illness and to risk-adjust adequately to account for differences in the severity of disease across regions.

Another approach to understanding better the causes of slow (or rapid) diffusion is to implement an intervention designed either to hasten (or depress) the speed of diffusion. One example would be to compare several approaches for encouraging the rapid diffusion of an effective medication such as naltrexone in general mental health practice. While we know some things about implementing effective treatments

(12,

52 –

59 ), systematic differences could still exist across regions with respect to physician and patient adoption.

For example, Skinner and Staiger

(60) found a strong correlation between the adoption of hybrid corn by farmers in the 1930s and 1940s and the adoption of beta-blockers in 2000/2001. They suggested one cause for the close correlation: social capital, defined as the presence (or absence) of social networks associated with civic participation, educational attainment, and cooperation among citizens

(61) . Social capital is unusually high in Iowa (a rapid adopter of both hybrid corn and beta-blockers) and low in Arkansas (a slow adopter of both). Similarly, Williams

(62) found a strong (negative) association between social capital and measures of profitable health interventions with potentially low marginal benefit, such as cesarean sections and hospital days in the last 2 years of life.

To sum up, we have identified several factors that affect the process of diffusion of mental health treatments. We suggest there is considerable potential in documenting and understanding regional variations in mental health treatments, if only to understand why some regions or institutions adopt so slowly (or so rapidly). Similarly, intervening in our existing mental health care system by addressing educational or attitudinal factors, financial barriers, or profitability can help to inform how each of these factors can be harnessed to improve the quality of care, or whether the best approach is to customize the intervention to the region or institution. Valuable lessons are also provided by interventional studies in other clinical areas, some of which foundered on organizational barriers to change when trying to implement evidence-based improvements

(63) . In the longer term, the objective is to better understand and overcome barriers that keep us from attaining best-quality mental health care in the United States.