Racial differences in drug abuse and its consequences have long been described, but the relative importance of genetic and social factors related to race and drug abuse is ambiguous

(1) . Health disparities between races may be mistakenly attributed to genetic variation when these disparities are of social and historical origin

(2) . Substance use disorders are heritable diseases that result from a complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Among the most highly heritable substance use disorders are addictions to cocaine (heritability, i.e., proportion of variance accounted for by genetic factors, 0.72), heroin (0.82), and alcohol (0.56), all three of which are drugs with moderate to high addictive potential

(3) . These heritability studies indicate that genetic variation plays a major role in differential vulnerability to addiction within populations, and they raise the question of whether differences in frequencies of vulnerability alleles contribute to racial disparities in rates of substance use disorders. To address this issue, we used genetic markers to estimate the degree of individual African and non-African ancestries in a group of subjects who were all self-identified as African Americans but who, on a genetic basis, showed wide variation in degrees of African, European, and Asian heritage. Populations of mixed ancestry, such as African Americans, provide an opportunity for examining the role of genetic factors in explaining observed differences in incidence between populations and, eventually, for locating alleles that contribute to dissimilarities in disease risk

(4) .

Drug use and illegal drug trafficking are major problems within African American communities of the United States

(5) . Illegal drug use is more common among African Americans than among Americans of European ancestry

(6) . According to the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, the 12-month prevalence of illicit substance use disorders in the United States is higher among African Americans (2.4%) than among Caucasian Americans (European Americans) (1.9%) (7, 8). In contrast, alcohol use and alcohol use disorders are more common among European Americans than African Americans

(7,

8) . Furthermore, adverse consequences of drug use appear to be more severe among African Americans. As compared to European Americans, African Americans have been shown to be at higher risk for dependence after initiation of cocaine use

(9), to be more likely to need treatment

(10), and to be twice as likely to die from drug- or alcohol-related causes

(6) .

Both environmental and genetic factors can account for racial disparities in substance use disorders and associated problems. Among the environmental risk factors, exposure to abuse and neglect in childhood, which are particularly common among some U.S. minorities, including African Americans

(11,

12), is a well-known risk factor for the development of substance use disorders among various ethnic groups

(13 –

15) . Broadly acting environmental conditions are also important determinants of health disparities in substance use disorders

(16 –

18) . Macrosocial factors moderating risk for substance use disorders are likely to reflect differences in economic resources, educational opportunities, societal and medical supports, levels of criminality, and availability of certain drugs within communities

(19 –

25) . Cocaine and heroin addicts tend to live in areas with higher rates of delinquency, crime, unemployment, poverty, crowding, and substandard housing

(19 –

22) . On average, African Americans have lower personal incomes, fewer years of education, higher unemployment, and higher rates of poverty (U.S. Census Bureau: Census 2000, http://factfinder.census.gov/) and are more likely to live in impoverished neighborhoods than European Americans

(18,

26) . Consistent with the idea that macrosocial factors moderate racial differences in rates of substance use disorders, one study showed that the risk for crack cocaine use did not differ between African Americans and European Americans living in the same neighborhoods

(27) .

Although only a small proportion (5%–7%) of genetic differences between individuals are explained by interpopulation differences

(28), numerous examples of interpopulation differences in frequencies of disease-causing alleles are known. So far, research studies on substance use disorders have evaluated only the impact of racial self-identification, which is primarily determined by social, political, and historical contexts

(1) and does not necessarily reflect genetic ancestry. More recently, the availability of ancestry-informative markers and reference populations representing worldwide genetic diversity have provided powerful tools enabling the elucidation of an overall worldwide pattern of ethnic factor structure as well as the quantitative assessment of individual ancestry

(4,

28 –

31) . Self-reported ethnicity is generally a suitable proxy for genetically inferred ancestry

(28) . However, whereas ethnic self-identification is generally a binary measure, the information provided by ancestry-informative markers captures gradations of genetic ancestry.

Our aim was to evaluate whether genetically measured ancestry contributes to interindividual differences in vulnerability to addiction in self-identified African Americans. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated whether the degrees of African and non-African ancestries measured with a panel of 186 ancestry-informative markers predicted risk of cocaine, opiate, and alcohol addiction in 407 substance-dependent individuals and 457 comparison subjects, all of whom identified themselves as African American. Self-identified African Americans are likely to share environmental exposures that are more common within this racial group than among other ethnicities. However, within this population there is wide variation in African and non-African ancestries. Although ancestry computed by ancestry-informative markers is a genetically inferred measure, it might also correlate with environmental exposures associated with risk. Therefore, we also tested whether African ancestry correlates with environmental factors moderating risk for substance use disorders, namely, exposure to abuse or neglect during childhood and socioeconomic status measured at the neighborhood level by using U.S. census data.

Method

Study Group

The human research protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) New Jersey Health Care System, East Orange Campus, and the New Jersey Medical School. After complete description of the study, all subjects gave written informed consent.

A series of 407 substance-dependent African American patients were seen in the substance abuse treatment program at the VA New Jersey Health Care System. Among these, 89% were male, and the mean age was 48.2 years (SD=7.5). The patients were all older than 18, met the DSM-IV criteria for substance dependence, identified themselves as African American, and had been abstinent for at least 2 weeks before the study. Abstinence was evaluated with three urine tests per week for illicit drugs and three breath-analyzer tests per week for alcohol. Excluded were patients with mental retardation, dementia, or acute psychosis. A total of 457 African American comparison subjects were recruited at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey from insulin-dependent diabetic outpatients seen at an ophthalmology clinic and from blood bank volunteers. Among the comparison subjects, 41% were male and the mean age was 32.6 (SD=7.1).

Psychiatric Assessment

A semistructured psychiatric interview, described elsewhere

(32,

33), was conducted by a psychiatrist (A.R.). The psychiatric status of the comparison subjects was determined by a semistructured screening interview. Comparison subjects with current or past history of addiction were excluded from the analyses. Among the patients, 250 individuals met the DSM-IV criteria for cocaine dependence, 171 met the criteria for opiate dependence, and 260 were alcohol dependent. These disorders were highly comorbid: 184 subjects were affected by both alcoholism and illicit substance use disorders (cocaine or opiate addiction), 147 subjects were affected by illicit substance use disorders without comorbid alcoholism, and 76 subjects were affected by alcoholism without comorbid illicit substance use disorders.

Assessment of Childhood Trauma

A subset of 490 subjects (including 310 patients and 180 comparison subjects) completed the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, which yields scores for childhood physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect

(34) . Reliability and validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire have been demonstrated

(34,

35) . The 28-item version was used for the comparison subjects, while the 34-item version was used for the patients with addiction. All scores were calculated by using the 28-item version, and clinical cutoff scores were applied to create dichotomous abuse variables

(36) . These data have been previously reported in studies of clinical risk factors for suicidal behavior in drug dependence

(32,

33) .

In the overall study group, including the patients and comparison subjects, 72% (355 of 490) reported experiencing at least one type of abuse or neglect. Childhood physical abuse (53%), physical neglect (40%), and emotional abuse (37%) were the most common types of childhood trauma experienced, followed by sexual abuse (25%) and emotional neglect (21%). Among the 355 participants who experienced childhood trauma, 28% (N=101) were exposed to only one type of trauma, 30% (N=105) reported two different types, 19% (N=69) reported three types, 14% (N=50) reported four types, and 8% (N=30) reported all five categories of trauma.

Neighborhood-Based Assessment of Socioeconomic Status

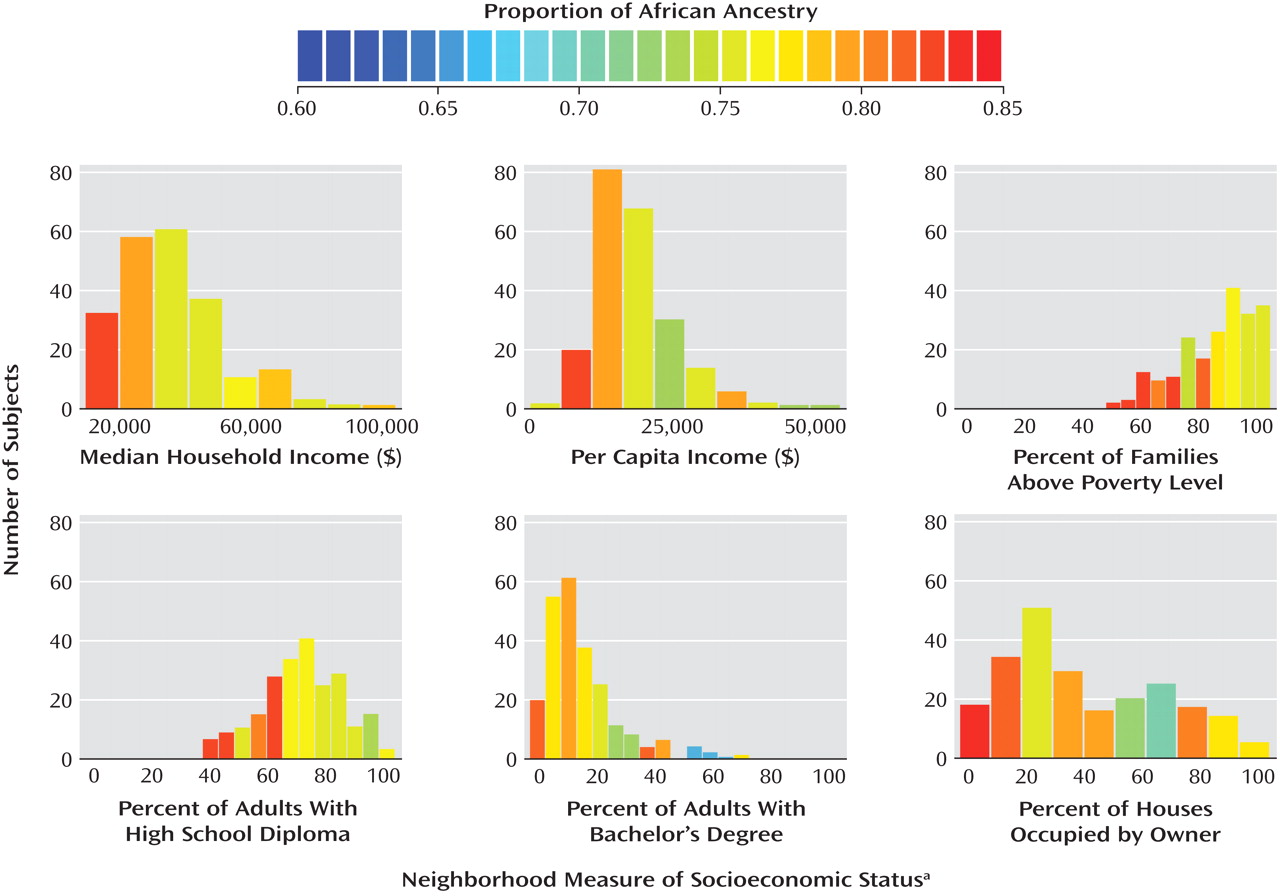

Characteristics of neighborhoods were ascertained by mapping the subjects’ addresses to the 2000 census tract boundaries (http://factfinder.census.gov). U.S. census tracts usually include 4,000–6,000 persons; census tract boundaries are determined in collaboration with local committees to represent demographically homogeneous areas approximating neighborhoods. Address matching was available for 228 cocaine-addicted patients, the majority (N=154) of whom were from New Jersey. We obtained 2000 census tract-level statistics, including median household income, per capita income, percent of families above the poverty level, percent of persons older than 25 years with high school diplomas, percent of persons older than 25 years with bachelor’s degrees, and percent of occupied housing units that are occupied by the owner. All variables were converted into categorical variables by using a median split.

Estimation of Ancestry

To characterize each individual for ethnic origin, 186 ancestry-informative markers were selected as previously described

(37) . In brief, each ancestry-informative marker was a genetically independent HapMap single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) that differed in allele frequency by at least 70% and 10-fold between at least two continental populations (from among Europeans, Africans, and Asians). The ancestry-informative markers were selected to be equally informative for these three continental populations. Genotyping was performed by using an Illumina GoldenGate Assay array (Illumina, San Diego). The ancestry-informative markers were also genotyped in the 51 worldwide populations represented in the Human Genome Diversity Cell Line Panel of the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) and Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH), which includes 1,051 individuals (http://www.cephb.fr/HGDP-CEPH-Panel).

We used Structure, version 2.2 (http://pritch.bsd.uchicago.edu/structure.html), to identify population substructure and compute individually measured ancestry scores. Structure 2.2 was run simultaneously on the ancestry-informative marker genotypes for African American patients and comparison subjects and for the 51 populations represented in the Human Genome Diversity Cell Line Panel. Thus, the ancestry of each subject was determined individually with reference to the panel of 1,051 individuals. This “anchored” approach yields a stable factor structure interpretable in the context of worldwide genetic diversity. The number of ethnic clusters (K) was defined by running the data with different K values and computing the probability of K=n. The seven-factor solution was optimal and closely replicates the seven-factor solution found by Rosenberg et al. for the same 51 reference populations determined with short tandem repeat markers

(28,

29) and SNPs

(29) . In particular, the African populations in the Human Genome Diversity Cell Line Panel are identified by a single African factor in the seven-factor solution.

Eigenstrat

(38) was also used to identify population substructure. Eigenstrat uses principal components analysis to model and graph ancestry differences between individuals along continuous axes of variation.

Statistical Analyses

Logistic regression was used to test the effect of childhood abuse or neglect on the odds of being diagnosed with a substance use disorder. Measured African ancestry was compared across diagnosis, childhood abuse or neglect, and neighborhood socioeconomic variables, by using standard least squares multivariate regression models. Gender and age were included as covariates in all the analyses. All statistical analyses were performed with JMP software, version 6 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). The criterion for statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

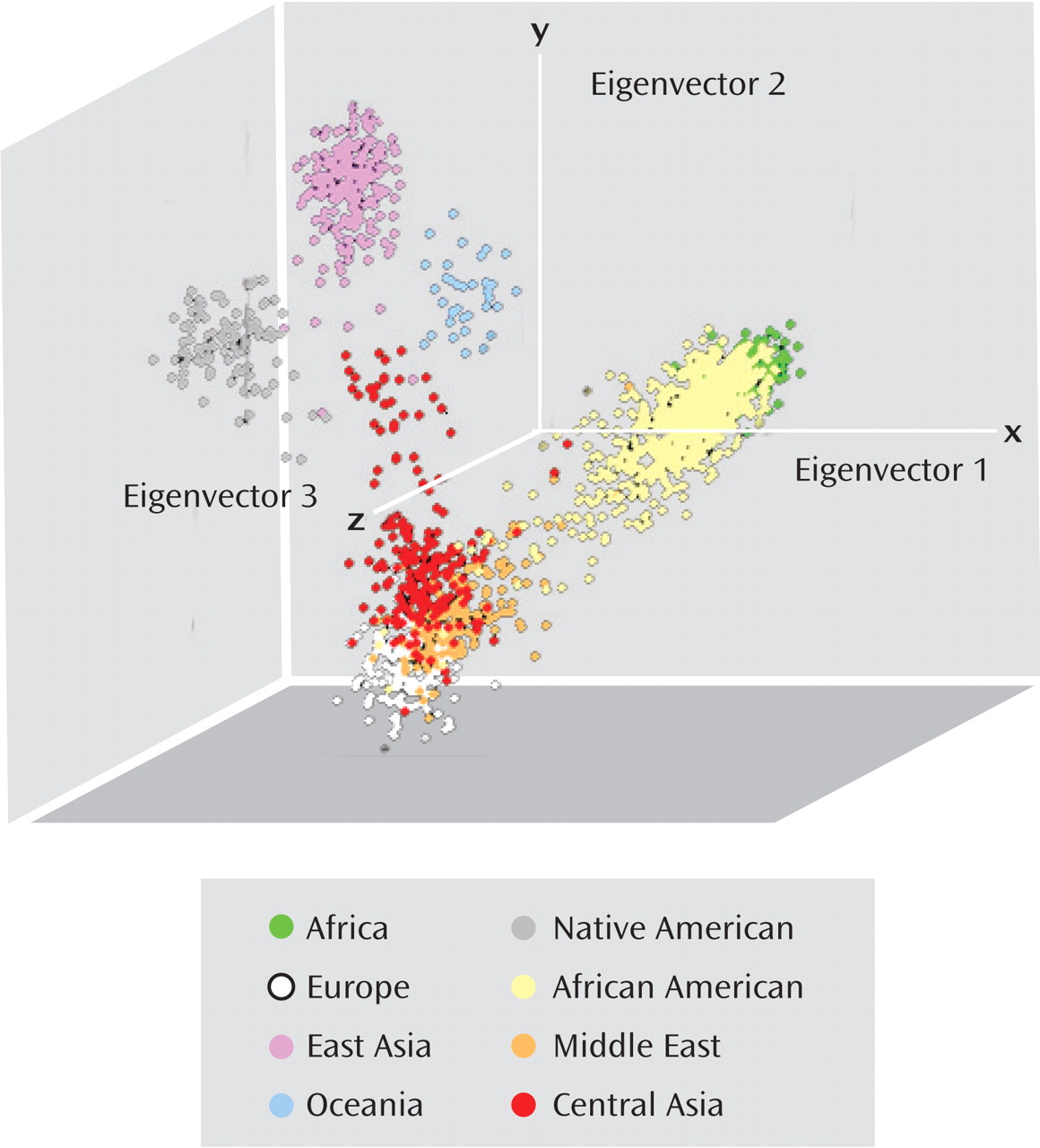

Ancestry-informative marker genotypes were analyzed by using a seven-factor solution that was found to be optimal for the 51 worldwide reference populations

(28) . These ethnic factors correspond to six continental regions (Africa, Europe, Oceania) and subcontinental regions (Middle East, Central Asia, East Asia) plus a factor for Native American ancestry. Overall, the African and European factors accounted for 86% of the variation in measured ancestry within the African American patients and comparison subjects. The mean proportions of each of the seven ethnic factors were as follows: Africa, 0.79 (SD=0.14); Europe, 0.07 (SD=0.09); Middle East, 0.05 (SD=0.06); Central Asia, 0.06 (SD=0.07); Native American, 0.01 (SD=0.02); East Asia, 0.01 (SD=0.01); and Oceania, 0.01 (SD=0.01). As shown in

Figure 1, the African American individuals we studied have a wide range of measured African ancestry, and they reside primarily in the vector space between the African and European genetic factor clusters or within the African genetic factor cluster.

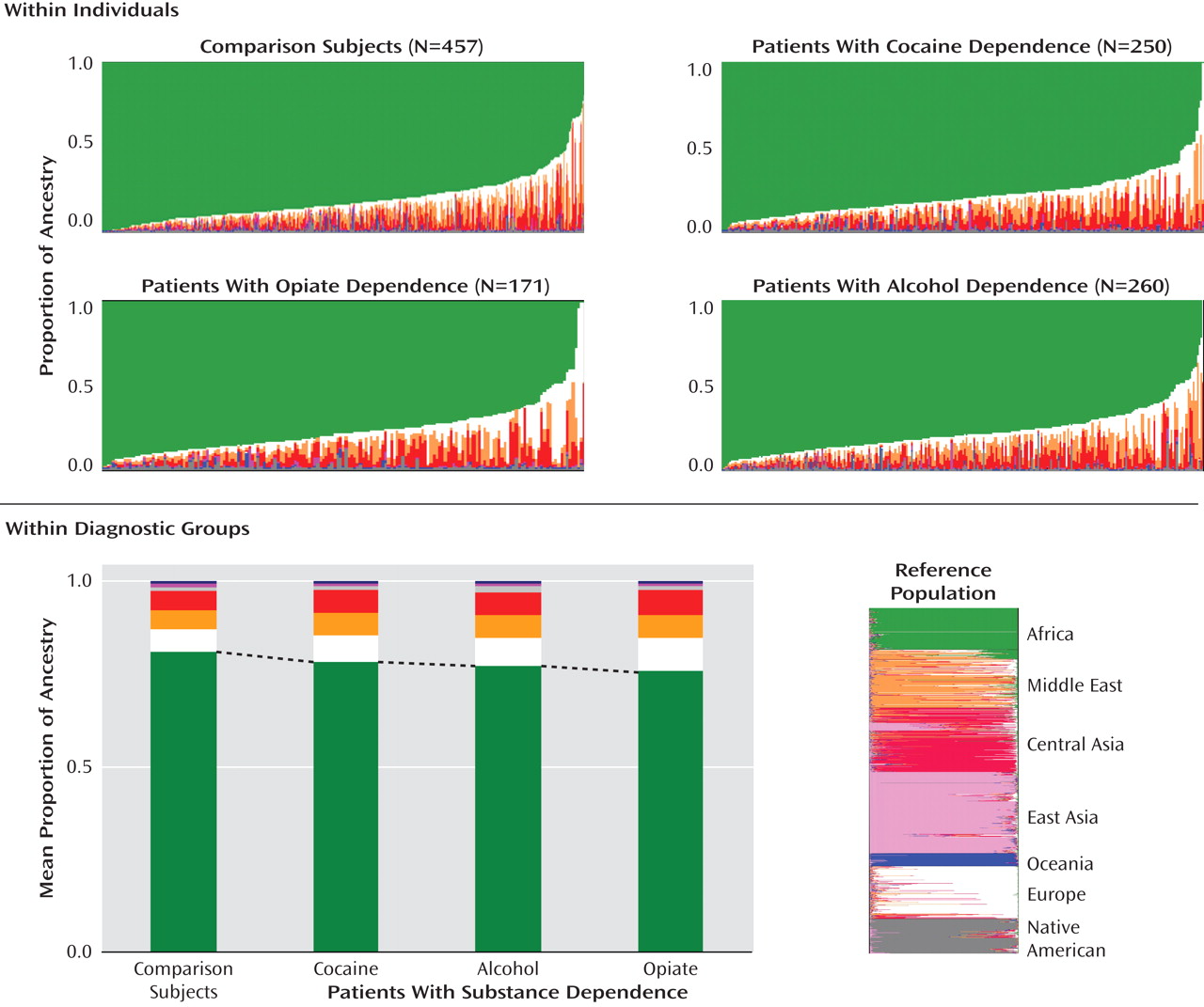

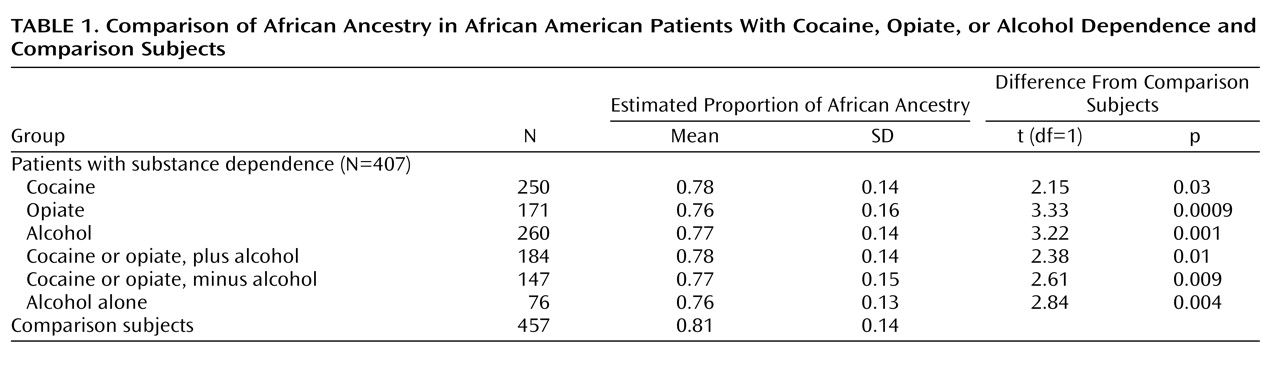

Proportions of African ancestry were significantly lower in the patients with alcohol, cocaine, or opiate dependence than in the comparison subjects (

Figure 2,

Table 1 ). The average differences were small, ranging from 5% (for opiate dependence) to 3% (for cocaine dependence). Since alcoholism is known to be more common among self-identified European Americans than among self-identified African Americans

(8), we evaluated whether differences detected in ancestry between the addicts and comparison subjects were driven mainly by alcoholism. African ancestry was compared between comparison subjects and patients affected by alcoholism alone, addiction to illegal drugs alone (i.e., cocaine or opiates), and addiction to both alcohol and illegal drugs. Consistently, the mean proportion of African ancestry was lower among the addicted patients than the comparison subjects, indicating that these differences were not driven by alcoholism (

Table 1 ).

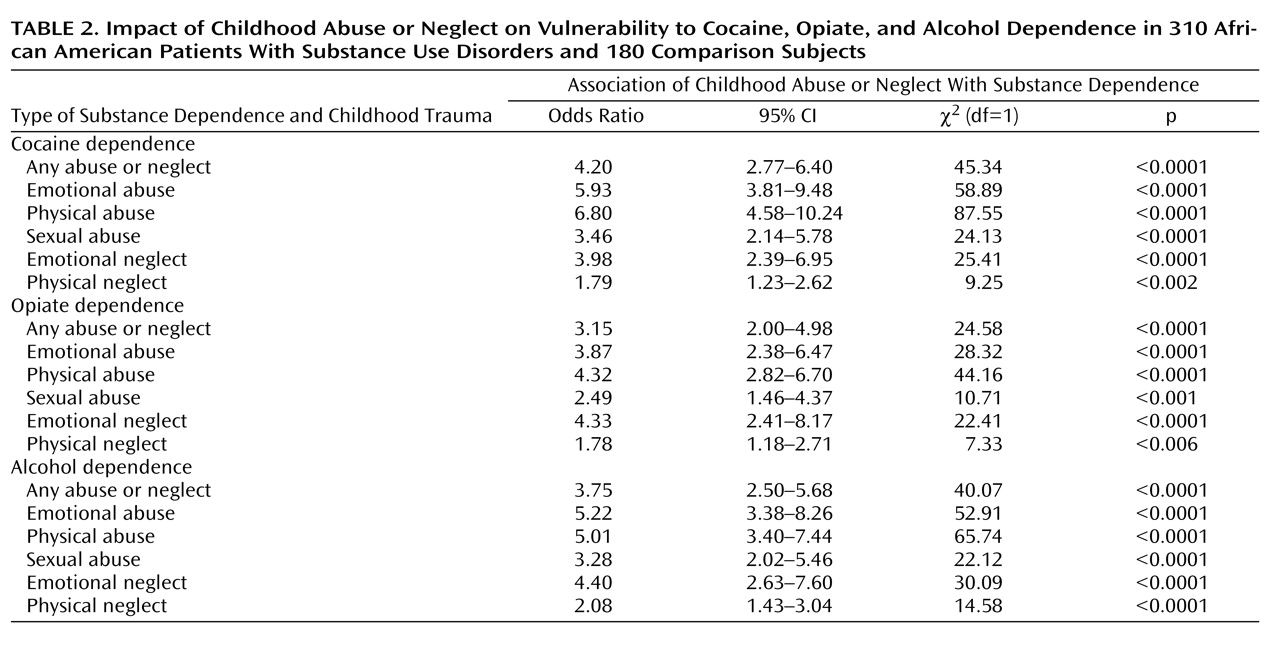

In this study group, exposure to abuse or neglect during childhood was strongly associated with addictions later in life. Among 310 patients with substance dependence and 180 comparison subjects, the score on each of the five Childhood Trauma Questionnaire subscales was associated with each substance use disorder, with odds ratios ranging from 1.78, for physical neglect among patients with opiate dependence, to 6.80, for physical abuse among those with cocaine addiction (

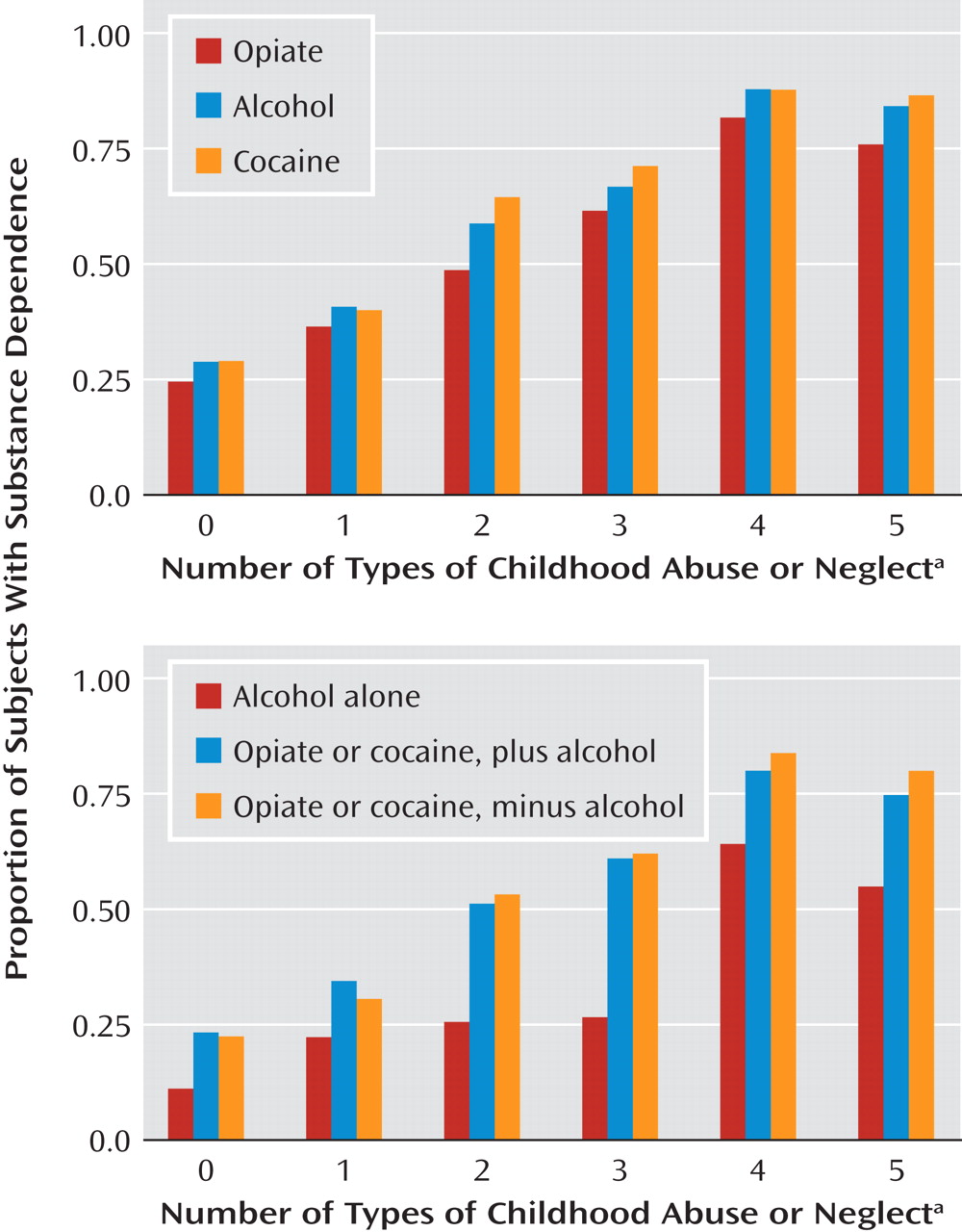

Table 2 ). The percentage of subjects suffering from substance dependence tended to increase in stepwise fashion with the number of types of childhood abuse and neglect experienced (

Figure 3, top). This stepwise effect of trauma was more evident for illicit substance use disorders than for alcoholism (

Figure 3, bottom).

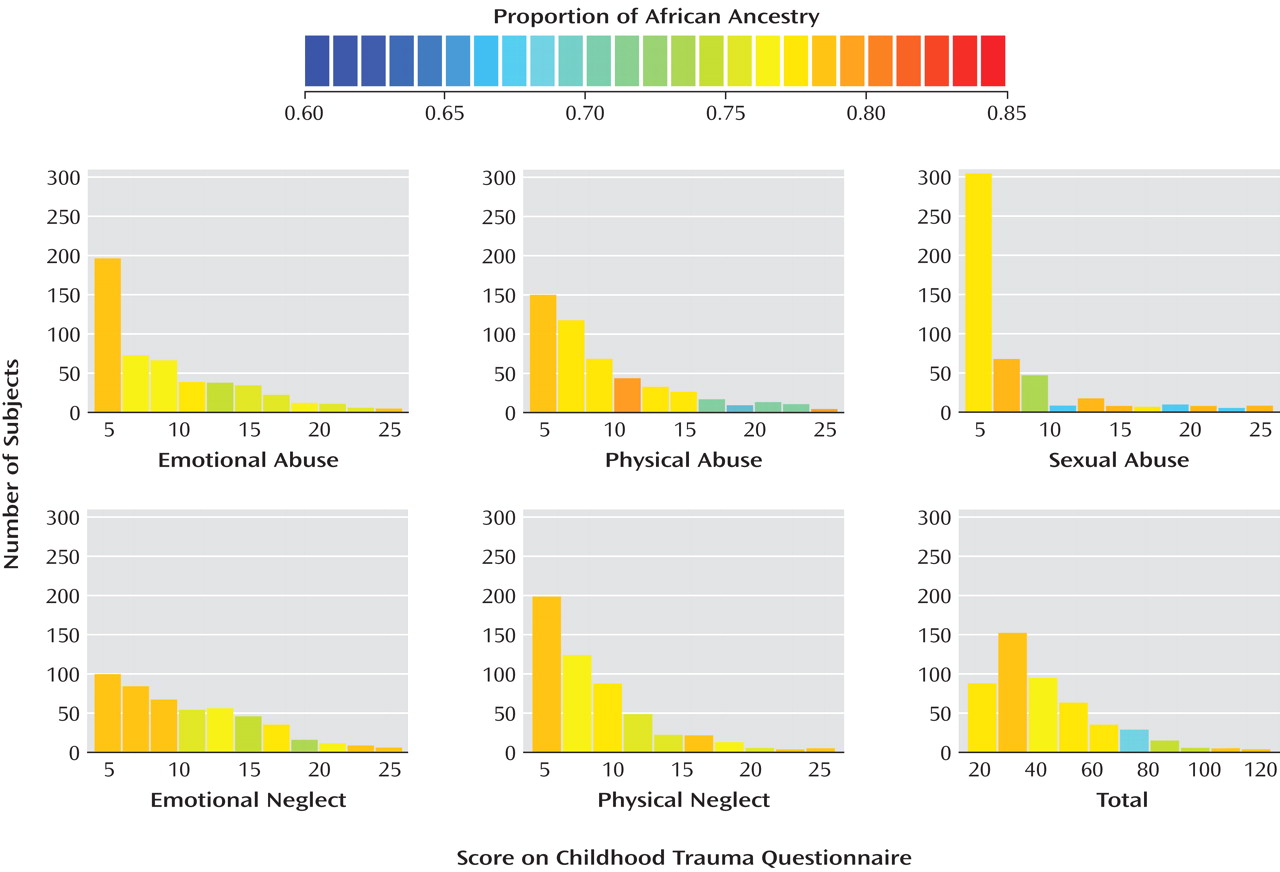

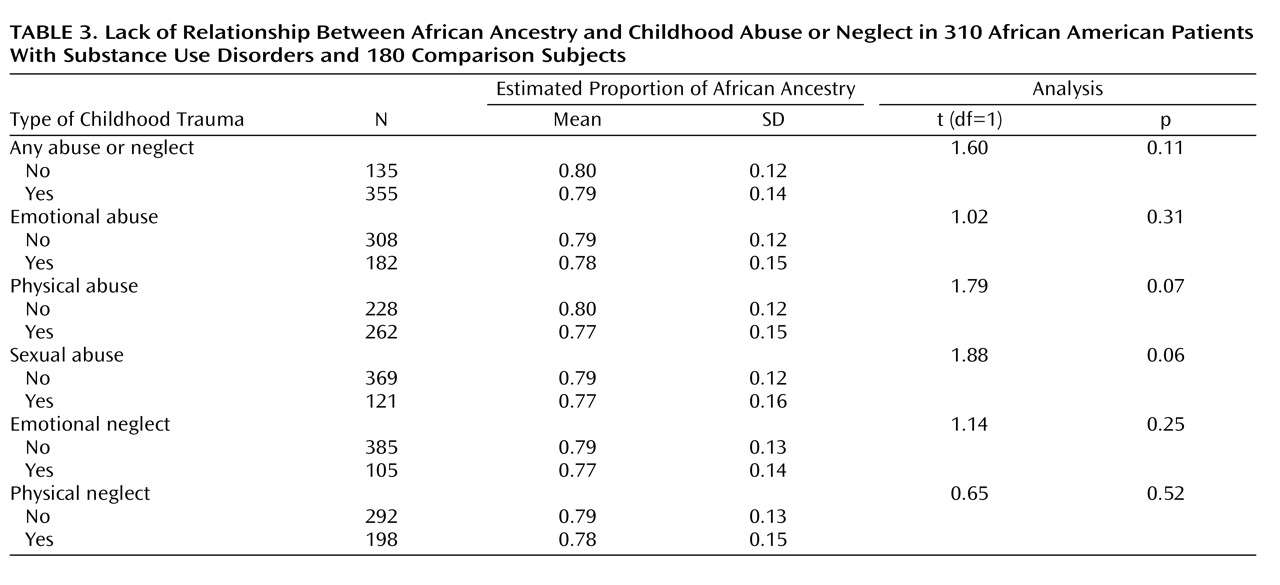

To test whether measured ancestry is associated with exposure to childhood abuse or neglect, we examined the degree of African ancestry in relation to both continuous (

Figure 4 ) and dichotomous (

Table 3 ) measures of childhood abuse and neglect. Levels of African ancestry were similar in the exposed and nonexposed subjects (

Table 3 ). However, while the differences were small, subjects who had experienced childhood abuse or neglect tended to have less African ancestry than individuals without childhood trauma; for two subscales these differences were of borderline significance: childhood physical abuse and sexual abuse.

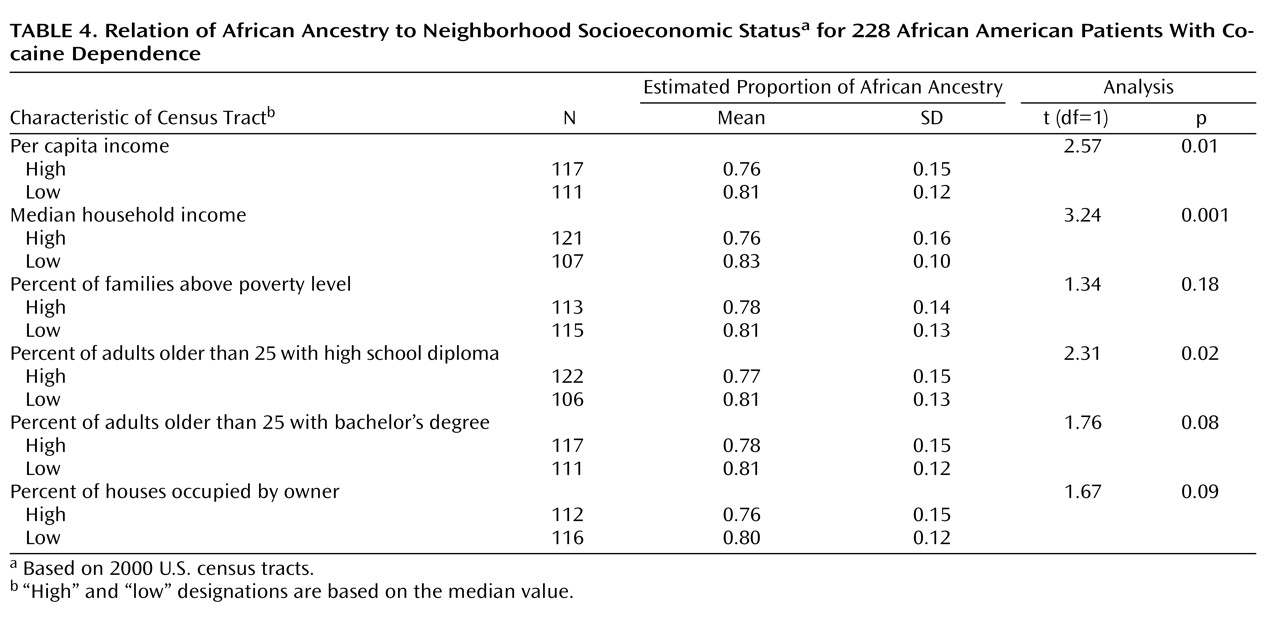

For 228 cocaine addicts matched to census tracts, subjects residing in census tracts with lower socioeconomic status tended to have higher degrees of African ancestry. These differences reached statistical significance for three neighborhood measures of socioeconomic status: lower per capita income, lower median household income, and lower percentage of census tract residents older than 25 years with a high school diploma (

Table 4,

Figure 5 ).

Discussion

The diversity of genetic origins among modern African Americans is well known. The majority of African Americans are descendants of enslaved Africans brought to America, in many cases more than 200 years ago. Many are also descendants of European Americans and American Indians. The African American population also includes recent immigrants from Africa and immigrants from the Caribbean, where other opportunities for admixture have occurred. Various African American communities have thus experienced different levels and types of admixture, and furthermore, massive internal migration within the United States has profoundly influenced their patterns of genetic diversity. The result is that the African American individuals we studied include a diversity of degrees of African ancestry, and within the group we studied, the admixture was primarily of European origin.

In this group, differences in measured ancestries between addicts and nonaddicts were small. However, the overall level of African ancestry was lower among cocaine, opiate, and alcohol addicts than among nonaddicts. These results indicate that African Americans are not as a group more genetically vulnerable to addictions. Indeed, the direction of the differences detected was the opposite of what might be expected on the basis of a simplistic comparison of the frequencies of addictions in African Americans and European Americans. In other words, some alleles conferring increased risk for substance use disorders may differ in frequency between populations, but on an overall basis those alleles are not more abundant in African Americans. Examples of protective alleles for addiction that show cross-population variation in frequency are two gene variants affecting alcohol metabolism (namely,

ADH1BHis47Arg and

ALDH2 Glu48Lys ). Neither of these alleles can explain the slight protective effect of African ancestry. Both of the alleles cause an adverse reaction to alcohol consumption, which in turn discourages further alcohol intake

(39,

40) . Both of these genetic variants are more common among Asian populations and might, in concert with cultural factors, contribute to the lower frequencies of alcoholism among Japanese and Chinese people than among other ethnic groups

(7) . It is plausible that further differences between populations in frequencies of variants that influence vulnerability to addictions exist, because at this point most of the genetic variation responsible for differential vulnerability to addiction is unknown.

An alternative hypothesis to explain differences in measured ancestry between patients with substance use disorders and comparison subjects is that these differences reflect the effect of environmental variables that correlate with genetic ancestry. However, if such a correlation exists, our results indicate that environmental factors other than neighborhood-ascertained socioeconomic status and exposure to abuse or neglect during childhood are likely to be responsible. In the locale we studied, subjects living in impoverished neighborhoods, who have been reported to have a higher risk of substance use disorders

(19 –

22), tended to display higher levels of African ancestry than subjects coming from wealthier neighborhoods. Also, exposure to abuse or neglect during childhood, which was a strong predictor of substance dependence, is not likely to account for the association we detected between smaller degrees of African ancestry and addiction because the mean level of African ancestry did not differ between individuals who were exposed and not exposed to childhood abuse or neglect.

The correlation we detected between ancestry and neighborhood socioeconomic status highlights the complex interrelation between genetic ancestral background and current social, economic, and environmental conditions in human populations. Self-identified African Americans might be thought to share relatively similar social contexts. However, within the locale we studied, the degree of African heritage correlated with poverty. An association between socioeconomic status and admixture proportion has been previously reported in a Mexican population

(41) . Social stratification and/or continuing gene flow from less admixed populations might contribute to the association between ancestry and socioeconomic status. The social environment of African Americans reflects a history of discrimination that has placed them at a position of disadvantage in society. The United States remains a society where place of residence is highly correlated with both race and socioeconomic status, and as found here, degree of African ancestry within African Americans. Social barriers between wealthy and poor neighborhoods may help maintain differences in allele frequencies. Indeed, in most societies, mating is strongly assortative with respect to socioeconomic status

(42) . Within this African American group, it is also possible that more recent and less genetically admixed immigrants from Africa or the Caribbean are more likely to reside in poorer neighborhoods, but we were not able to directly address this possibility.

The strength of this study is that we were able for the first time, to our knowledge, to investigate interconnections between ancestry, childhood trauma (an important individual environmental factor), and macroenvironmental factors for the origins of substance use disorders. The major limitation is that we did not assess several other environmental factors that are important mediators of vulnerability to addiction and that are likely to correlate with genetically measured ancestry. In this regard, psychosocial correlates of substance use disorders include a wide range of factors, such as social class, education, income, parental monitoring, peer deviance, drug exposure, religiosity, and parent-child relations, and only some of these important factors were evaluated in the current study.

Limitations include our inability to represent the general U.S. African American population with a study group derived from one locale. Also, the clinically based ascertainment of cases may limit the generalizability of these results.

In conclusion, our results indicate that vulnerability alleles for substance use disorders are not likely to be more abundant among African Americans. Differences in genetically inferred ancestry between African American addicts and nonaddicted comparison subjects were overall small, and African ancestry was actually lower among substance-addicted individuals. Juxtaposed with the small positive effect of African ancestry were the large negative effects of childhood abuse or neglect (not associated with ancestry). Future studies conducted on epidemiological samples characterized for genetic ancestry as well as for psychosocial factors are needed to better disentangle the effects of genetic and environmental factors underlying interpopulation differences in vulnerability to addiction. A cross-disciplinary response is needed because of the challenges posed by health disparities and the complex interconnections between genetic background and life experience.