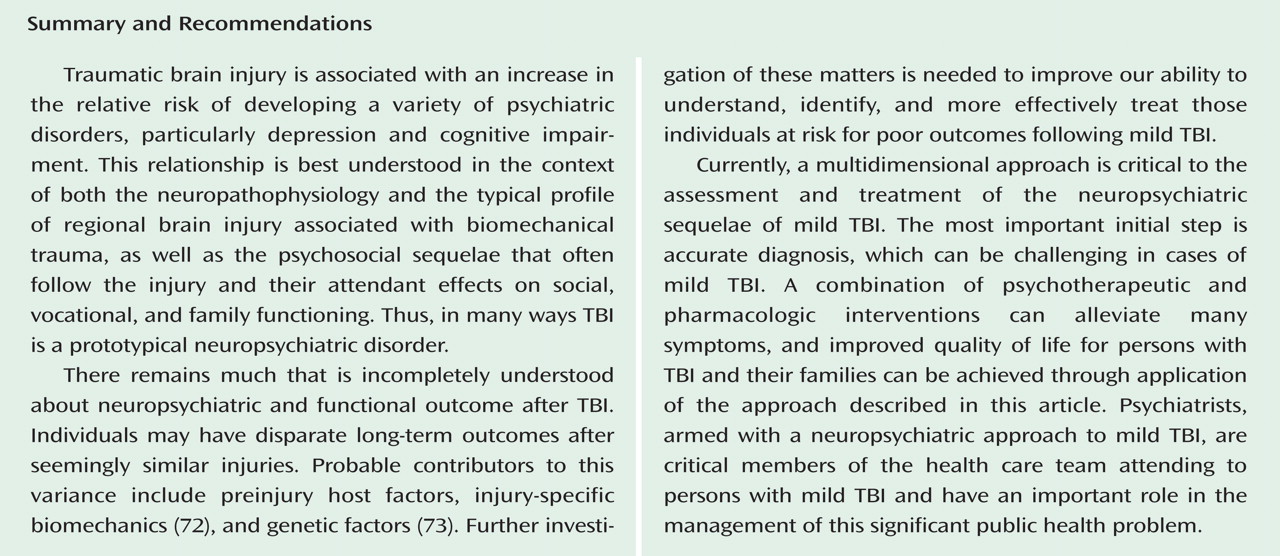

It is appropriate to use the standard diagnostic criteria for depression when evaluating persons with TBI

(43 –

45) . Although many factors may produce or contribute to apparent depressive symptoms, such as sleep disturbance, fatigue (anergia), difficulty with concentration, and anhedonia (apathy), when there are sufficient symptoms to merit a diagnosis of depression—regardless of their possible causes—treatment should be initiated. Treatment should be promptly initiated both to improve mood and to mitigate its adverse effects on cognitive, behavioral, physical, and psychosocial functioning

(36,

38,

40,

41,

46) .

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy may not only alleviate the mood disturbance but also reduce other postconcussive symptoms and the patient’s experience of the severity of such symptoms

(36) . When pharmacotherapy is initiated, a “start low and go slow” approach is recommended. Common clinical experience, as well as a limited body of literature

(19,

27,

31), suggests that persons with TBI may be more susceptible to the side effects of many psychotropic medications, suggesting a heightened need for vigilance for such effects when prescribing psychotropic agents in this context. Additionally, no medications have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration specifically for the treatment of post-TBI depression, or for any other posttraumatic neuropsychiatric problem. The use of these agents is therefore “off-label” and will in each case be a matter of empiric trial. Nonetheless, the literature describing the treatment of posttraumatic depression is a useful guide to treatment selection.

As reviewed by Warden et al.

(47), several studies, mostly small and open-label, suggest that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants may improve depression following TBI. Given concerns about the tolerability of tricyclic antidepressants, particularly their potentially adverse anticholinergically mediated effects on cognition

(19), the SSRIs are generally regarded as the first-line agents for treatment of depression following TBI

(47) .

Among the SSRIs, the available evidence favors sertraline (25–150 mg/day)

(36,

48) or citalopram (>20 mg/day)

(46) . Ashman et al.

(49), in a 10-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 52 patients with remote, predominantly moderate to severe TBI, observed significant improvements in depressive symptoms in those treated with 25–200 mg of sertraline daily (mean dose not specified) or placebo. With treatment response defined as a change of 50% or more in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score, 59% of patients receiving sertraline responded, while only 32% of those treated with placebo responded. Although the magnitude of improvement and the number of treatment responders were similar to those observed in pharmacotherapy studies performed in patients with idiopathic major depressive disorder, the response rate did not differ significantly between the number of sertraline and placebo responders. This observation most likely reflects a sample size inadequate to detect a significant difference in responder rates. The mean dose of sertraline received by these patients was not reported in the study, leaving uncertain the adequacy of antidepressant dosing.

Other SSRIs may be used to treat depression after mild TBI, although the literature provides little guidance regarding their efficacy and tolerability in this population. In everyday practice, the effectiveness and tolerability of fluoxetine does not appear to differ from that of the other SSRIs. However, its robust inhibition of cytochrome P450 (CYP450) 2D6, 2C19, and 3A, its metabolism to norfluoxetine (also an inhibitor of the P450 isoenzymes), and the prolonged half-life of this active metabolite are concerning: the risk of drug-drug interactions or metabolism-related adverse events may be higher with this SSRI than with sertraline or citalopram. Paroxetine, also a potent inhibitor of CYP450, may impair cognitive function even in healthy adults, most likely as a result of its antimuscarinic effects

(50) . Paroxetine therefore is best used with caution, if at all, in persons with posttraumatic depression and cognitive complaints.

The efficacy and tolerability of other antidepressants (including “dual action” antidepressants and bupropion) in this population has not been established, but common clinical experience suggests that the benefits and adverse effects of most of the newer-generation antidepressants are similar to those of the SSRIs. The propensity of bupropion to reduce seizure threshold is a concern in the first-line use of this agent, although the risk of early and late seizures after mild TBI is relatively low

(51), and the risk of seizures with bupropion appears to be restricted to the immediate-release formulation

(52) . If bupropion is used in patients with mild TBI, preference should be given to its sustained-release formulation, and vigilance for treatment-related seizures should be maintained.

In addition to effects on depressive symptoms, SSRIs may improve comorbid posttraumatic somatic, behavioral, and cognitive problems. Fann et al.

(36) demonstrated sertraline-related improvements in postconcussive symptoms, including headache, fatigue, and sleep disturbance, as well as reduction in the perceived severity of injury and improvement in psychosocial functioning. Fann et al.

(41) also reported that sertraline-related improvement in post-TBI depression was accompanied by improvements in psychomotor speed, recent verbal memory, recent visual memory, and general cognitive efficiency, as well as patients’ perception of the severity of their cognitive problems. Horsfield et al.

(53) observed similar benefits in a small series of patients with TBI treated with fluoxetine.

The benefits of antidepressants for posttraumatic cognitive impairments have not been observed in all studies. Lee et al.

(54), comparing the effects of sertraline and methylphenidate on depression after mild to moderate TBI, reported reductions of depressive symptoms with both agents, but more substantial improvements in cognition and daytime fatigue with methylphenidate. Similar benefits of methylphenidate monotherapy for depression after TBI have been reported by other authors

(55) . These observations suggest that some patients with significant depression, fatigue, and cognitive impairments after TBI may experience improvements in all of these domains in response to a single agent, methylphenidate. In practice, however, the use of methylphenidate in the treatment of depression is generally limited to augmentation of a standard antidepressant and targets residual depressive, anergic, or cognitive impairments.

Psychotherapy

Psychological and social factors contribute to the development and persistence of posttraumatic depression. Education regarding TBI and recovery expectations, reassurance, and frequent support are associated with better outcomes during the first year after the injury was sustained

(29,

30), and multidisciplinary treatment may be particularly useful for individuals with mild TBI and prior psychiatric problems

(56) . Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may be useful for a variety of posttraumatic neuropsychiatric problems. CBT has been observed to decrease depression, anxiety, and anger and to improve problem-solving skills, self-esteem, and psychosocial functioning after TBI, although the benefits of such psychological improvements on depression are observed inconsistently

(57 –

59) .

Spouses, families, and caregivers of persons with TBI frequently require psychotherapeutic intervention to aid them in maintaining both their own psychological health and that of their injured family member. Depression occurs more frequently in caregivers of persons with TBI

(60), and posttraumatic depression is strongly associated with significant family dysfunction

(61) . Use of problem-solving and behavioral coping strategies by the patients’ families can decrease the severity of depression

(62) . Thus, engaging spouses, family members, and other care providers in the treatment of posttraumatic depression is essential. Peer support programs for persons with TBI and their families increase their knowledge about TBI, improve general outlook, enhance their ability to cope with depression, and improve quality of life after TBI

(63) .