There is now a large body of evidence concerning the serious long-term effects of childhood sexual abuse

(1), which include an increased vulnerability to suicide

(2 –

7) . Sexual abuse is more commonly reported by women

(8 –

10) . Since both sexual abuse and suicide attempts are more prevalent in women, it is possible that the former may contribute to the latter

(11,

12) .

In the present study, we hypothesized that in women, relative to men, 1) a history of both sexual abuse and suicide attempts would be more common, 2) the association of sexual abuse with suicide attempts would be more robust, and 3) the proportion of suicide attempts attributable to sexual abuse would be greater. We also examined the extent to which the effect of sexual abuse is modified when current affective symptoms are taken into account. Suicide attempts do not occur out of the blue but from a background of suicidal ideation (

13 ; unpublished data also available upon request from Bebbington et al.). Thus, we repeated these analyses in relation to suicidal intent on the grounds that parallel findings would add support to our primary results.

Method

We utilized the analysis of data from the 2000 British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. The methods used in the survey have been described in detail by Singleton et al. and Meltzer et al.

(14 –

16) .

Sample

Interviews with prospective volunteers were conducted in 2000. Addresses were selected using the Postcode Address File, from which 438 postal sectors (encompassing Great Britain, except the Highlands and Islands of Scotland) were selected randomly. From these postal sectors, 36 delivery points were randomly chosen in each sector, resulting in a total of 15,804 delivery points. Among these delivery points, 14,285 were private households and 12,792 had at least one person between the ages of 16 and 74 years old. A single individual was selected from each household using the Kish grid method

(17) . Among adults selected, 8,886 were identified as being capable of participating in the survey, and 8,580 were eventually interviewed, an overall response rate of approximately 70%.

Data Gathering

Data were established by interviewers from the Office for National Statistics (formerly the Social Survey Division field force of the British Office for Population Censuses and Surveys). The interviewers were experienced, with many having worked on previous surveys of psychiatric morbidity. Interviewers were trained specifically in the procedures and methods of the 2000 British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. All participants were informed about the study procedures before giving their written consent. Ethical approval was granted by the London Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee, and all relevant local research ethics committees were informed.

The interview consisted of general information gathering (sociodemographic data, general health, and intellectual functioning) and assessment of common mental health problems. Participants were asked if they had ever made an attempt to commit suicide by taking an overdose of pills or in some other way. Suicide attempts were recorded separately from acts of self-harm, which were not considered for the present study. Our primary analysis was based on lifetime history of suicidal attempts. We also analyzed suicidal intent, which, in the present study, applies specifically to positive endorsement of a question in the survey concerning the explicit consideration of suicide as a course of action. This was chosen to form the basis of a secondary analysis because it comprises the most severe form of suicidal ideation reported in the British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity (unpublished data available upon request from Bebbington et al.).

Respondents were shown cards listing a number of victimization events. One of these events was sexual abuse, and participants were asked whether they had ever experienced this form of abuse. We chose to focus on a history of sexual abuse because of its strong association with psychiatric morbidity

(18) . The survey did not provide data on the severity of the experience.

Nonpsychotic mental illness was assessed using the Clinical Interview Schedule–Revised (CIS–R

[19] ). CIS–R has many advantages. For example, it can be administered by trained nonclinical interviewers; the training is easy for experienced interviewers to learn; and the interview itself can be carried out in approximately 30 minutes. Additionally, it provides a total score based on the panoply of neurotic symptoms. The score relates to the week before the survey and was used in the present study as an indicator of current affective disturbance.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using STATA version 10.0

(20), which enabled weighting (in order to account for the sampling design and nonresponse) and also permitted us to calculate robust confidence limits. We determined actual numbers and weighted proportions, with all analyses of statistical significance being based on weighted data. We also determined odds ratios and the population attributable risk fraction for both sexes. The odds ratio provides a measure of the strength of association between abuse and suicide attempts, while the population attributable risk fraction allows for an estimate of the proportion of suicide attempts that can be ascribed to exposure to sexual abuse. In theory, the population attributable risk fraction indicates how much the suicide attempt rate would be reduced if no sexual abuse occurred in the population. As such, it is dependent on both the prevalence of the exposure to sexual abuse in the population and the strength of the association of sexual abuse with suicide attempts. The relative effect of gender and sexual abuse on lifetime suicide attempts and on attempts within the past year was established by logistic regression analysis (only two respondents reported an attempt in the past week). We then incorporated the effect of the total CIS–R score in order to test our hypothesis that affective symptoms mediated the relationship between sexual abuse and a history of suicide attempt. Thus, we relied on generally accepted criteria for mediation

(21), which required that 1) sexual abuse be associated with suicide attempts and with the total CIS–R score and 2) the odds ratio for the relationship of sexual abuse to suicide attempts be reduced by adding CIS–R scores to our logistic regression model.

Finally, in order to test the consistency of our findings, particularly the relationship with affective symptoms, we repeated the analyses using lifetime suicidal intent, suicidal intent in the past year, and suicidal intent in the past week as dependent variables. This is justified by the close association between suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (unpublished data available upon request from Bebbington et al.).

Results

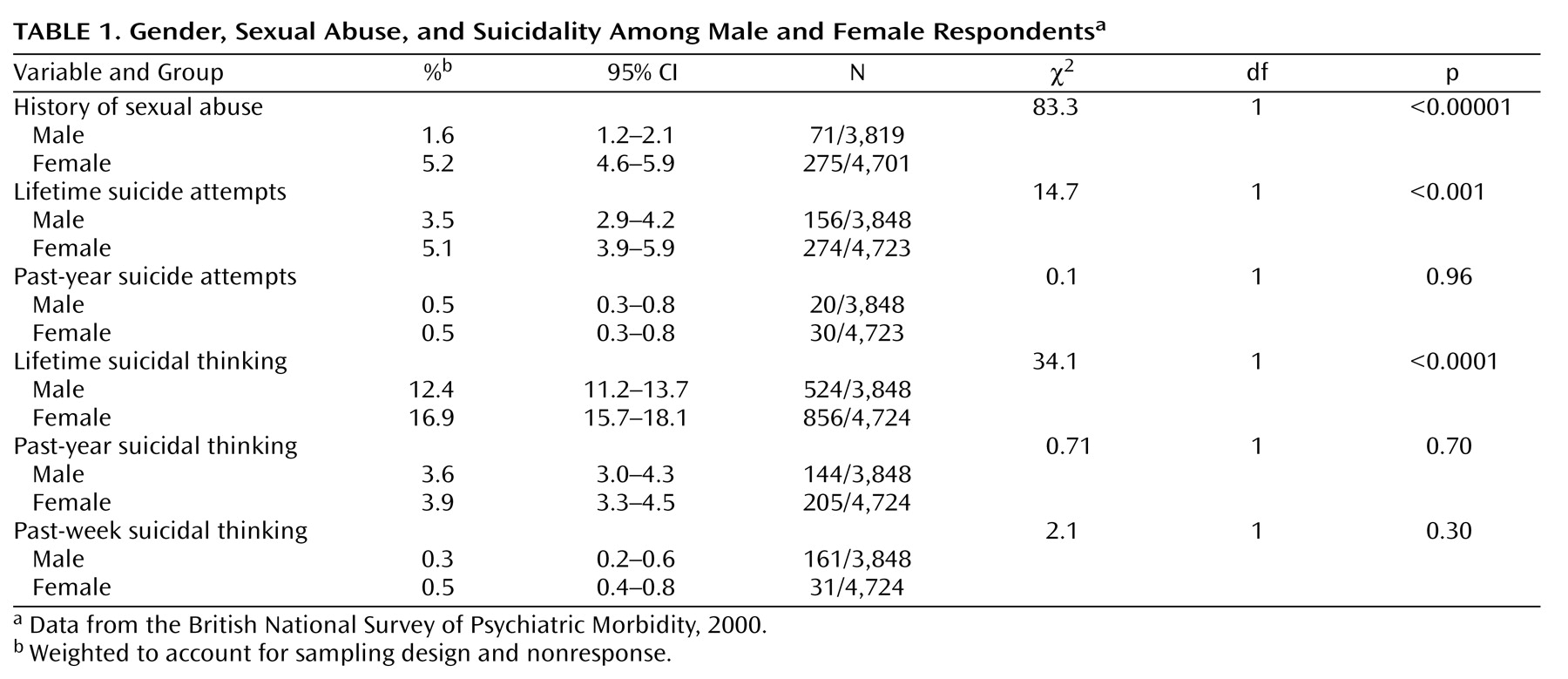

Among respondents, 430 (4.4%) admitted to at least one suicide attempt over the course of their lives, and 50 (0.5%) reported at least one suicide attempt in the past year. Although women were significantly more likely than men to acknowledge suicide attempts during the course of their lives, the frequency in the past year was equal between the sexes. A parallel pattern was found for lifetime suicidal intent, with 12% of men and 17% of women reporting suicidal intent over their lifetime (a significant difference), but there were no differences between the two groups over the past year or past week. Sexual abuse was reported by 3.5% of the survey population and was considerably more common in women than men (5.2% versus 1.6% [

Table 1 ]).

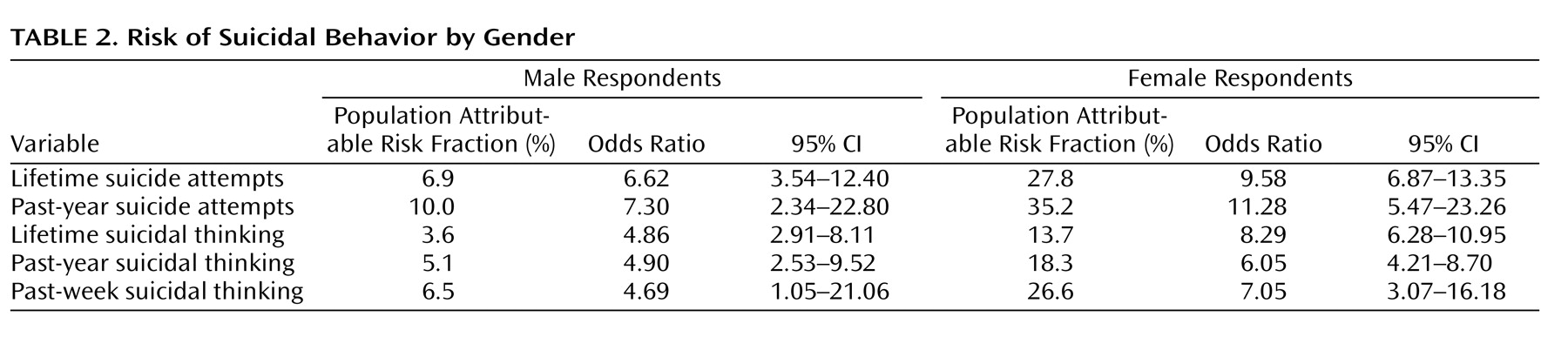

The odds ratio of sexual abuse for lifetime suicide attempts was high overall but higher in women (odds ratio=9.6; 95% confidence interval [CI]=6.87–13.35) than in men (odds ratio=6.6; CI=3.54–12.40). The odds ratios for the various measures of suicidality were uniformly greater in women than in men, although the confidence intervals were rather wide. The population attributable risk fraction for lifetime suicide attempts was 27.8% in women and 6.9% in men. The same wide discrepancy was apparent for the other measures of suicidality, but the population attributable risk fraction was less for suicidal intent than for actual attempts (

Table 2 ).

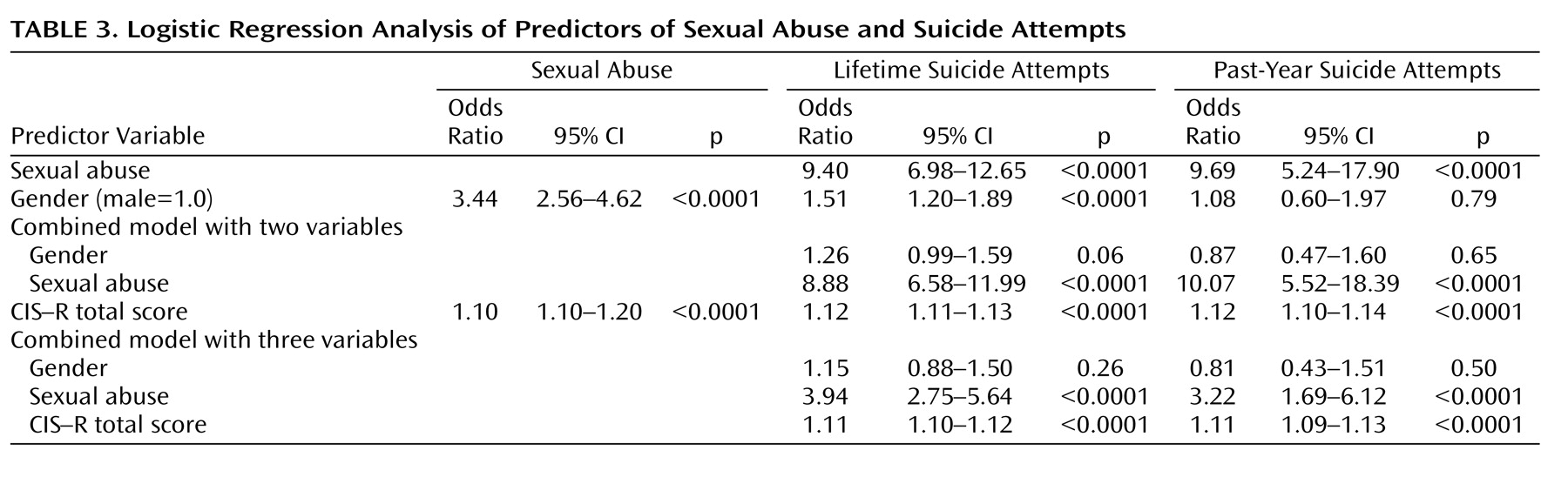

Pairwise analyses among gender, sexual abuse, CIS–R total score, and history of suicide attempts were performed (

Table 3 ). The effect of incorporating gender and sexual abuse simultaneously as independent variables in the model relating to attempted suicide was then analyzed. Finally, the effect of adding the total CIS–R score to the model was assessed. The unadjusted effect of sexual abuse on attempted suicide was particularly strong, being associated with a near 10-fold increase, whether the attempt took place over the participant’s lifetime or in the past year. Being female was associated with a more modest (but still highly significant) odds ratio of 1.51. When sexual abuse and gender were entered into the model together, there was a slight reduction in the odds ratio associated with sexual abuse and a proportionately greater reduction in the odds ratio associated with gender. The latter ceased to be significant at conventional levels of significance.

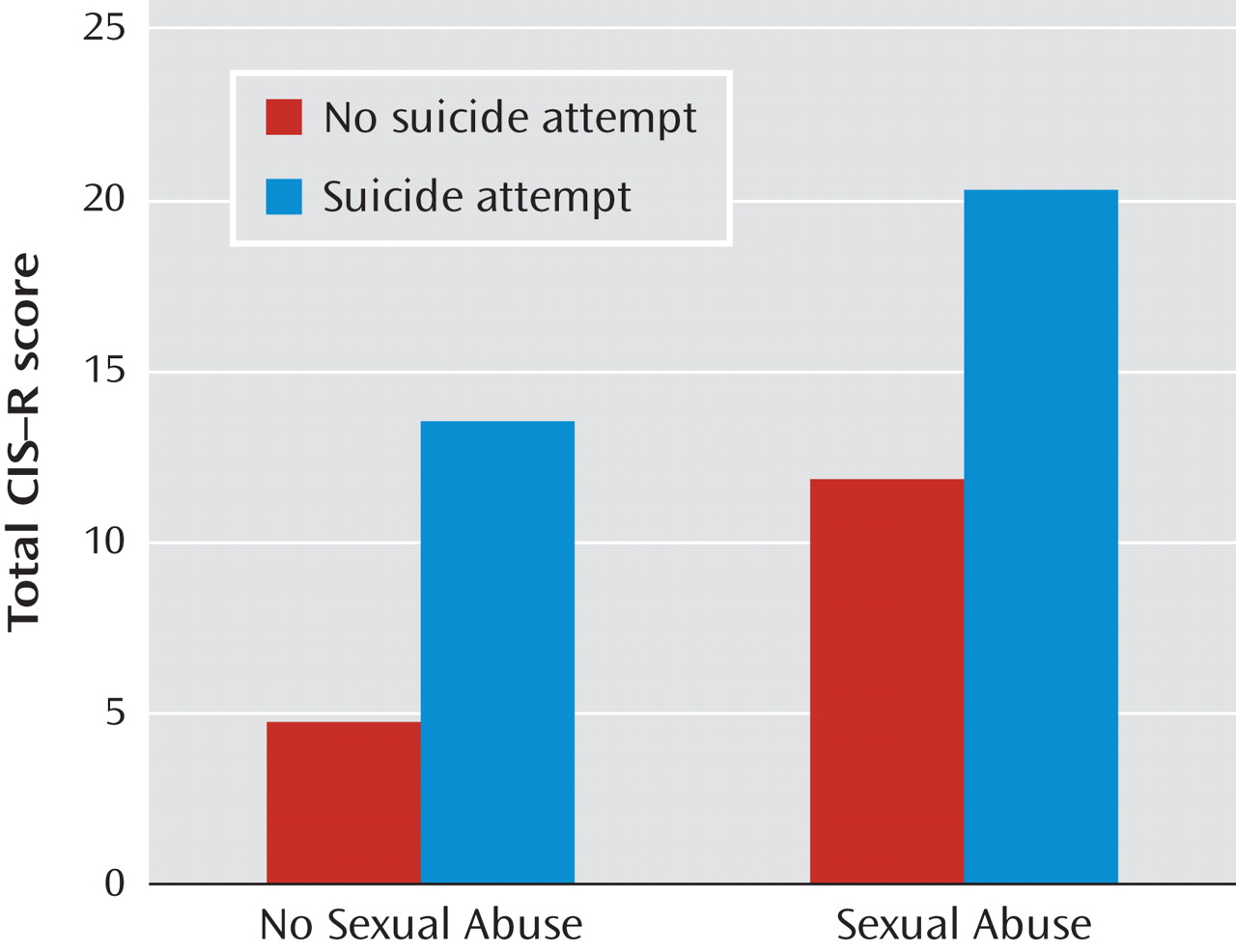

The CIS–R total score was strongly associated with both suicide attempts and sexual abuse. When the CIS–R total score was added to the model containing both gender and sexual abuse, there was a further small reduction in the gender odds ratio. However, the odds ratio for sexual abuse was reduced to less than one-half of what it was before the introduction of the CIS–R total score.

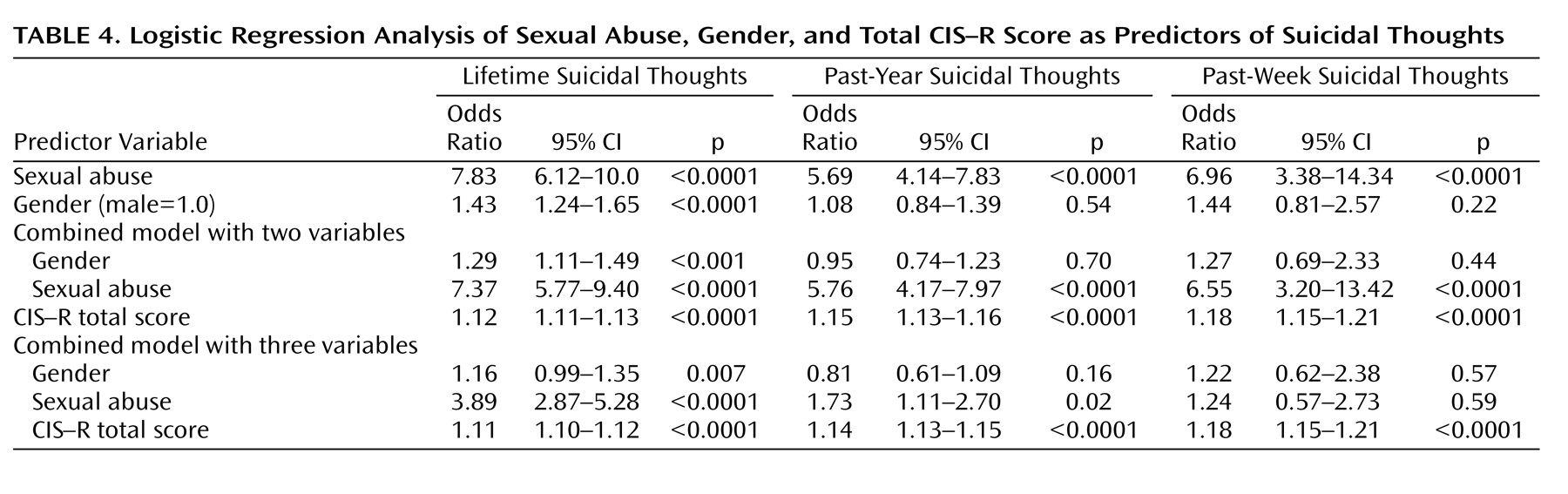

When we repeated the analyses using suicidal intent in the past week, in the past year, and over the life course as dependent variables, the results were similar (

Table 4 ). Sexual abuse was strongly related to suicidal intent in all time frames (as it was to suicide attempts). Women were no more prone than men to suicidal thoughts, and the introduction of sexual abuse and gender together as independent variables scarcely reduced the relative odds of sexual abuse. However, the salient finding from these analyses is that using the shorter time frames increased the effect of the CIS–R score on reducing the association between sexual abuse and suicidal intent. The implication is that affect strongly mediated the link between sexual abuse and suicidal phenomena. Sexual abuse probably has a tonic effect on increasing dysphoric mood, such that sexually abused persons require less deterioration in their affect to place them in the danger zone for suicidality (

Figure 1 ).

Discussion

In the present study, suicidality was common, with one-sixth of participants having considered suicide at some time in their lives and 4% reporting suicide attempts. Sexual abuse was more common in women (5%) than in men (<2%). The female-to-male odds ratio for sexual abuse was 3.4. This coheres with findings in the literature

(10), although there is dispute about whether the reduced rates of reported abuse among men is a result of the relative rarity of the experience or a relative reluctance to report the experience in this population. This caveat applies to our own data. Nevertheless, increased awareness of the problem of suicidality in recent years may have encouraged greater openness of survey respondents in both sexes.

The prevalence of suicidal lifetime thoughts and attempts were similar to those found in a cross-national comparison using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule

(22) as well as in findings reported in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing

(23) . Other similar general population surveys have reported both higher

(24) and lower

(25,

26) prevalences, discrepancies at least partly attributable to methodological differences.

In the present study, a history of sexual abuse was associated with a greatly increased history of lifetime suicide attempts (odds ratio=9.4). The high odds ratio for lifetime suicide attempts was replicated for attempts in the past year and for suicidal intent in all time frames. Other published studies have identified the effect of sexual abuse on suicidal behavior

(2 –

7) .

In women, the population attributable risk fraction of suicide related to sexual abuse was substantial, suggesting that in the absence of sexual abuse the female rate of suicide attempts over a lifetime would fall by 28%, relative to 7% in men. This tendency was replicated over all time frames for suicide attempts and suicidal intent. To our knowledge, the only other population study to examine these issues (in Southern Australia) did not report on gender differences but recorded a population attributable risk fraction of 11.9% for both genders combined when examining the association between recent suicidal ideation and sexual abuse

(27) . In the present study, a similar overall population attributable risk fraction for suicidal thinking in the past year was determined as 5.1% for men and 18.3% for women. The Australian study also considered the association between other specific traumatic events and suicidal ideation. For example, the population attributable risk fraction for sexual molestation was only exceeded by that for witnessing someone being badly injured or killed, being threatened with a weapon, being held captive, or being kidnapped.

The results were then further adjusted by including gender and sexual abuse as independent variables in the same logistic regression analysis. As we observed, the proportion of women reporting suicidal phenomena was only in excess when lifetime rates were used. Nevertheless, the addition of sexual abuse to the logistic regression uniformly resulted in a rebalancing, relatively reducing the association of female sex with suicidal phenomena. This suggests that a considerable proportion of suicide attempts and suicidal intent among women might be driven by the experience of sexual abuse.

Since we were interested in determining whether the influence of gender and sexual abuse on suicide attempts might be mediated by affect, we controlled (in our final analyses) for affective symptoms, as measured by CIS–R. The link between current affective state and prior suicidality was strong, since each unit increase in the CIS–R score increases the likelihood of a history of attempted suicide by approximately 10%. Including the CIS–R score did reduce the odds ratios of other variables, particularly in the case of sexual abuse. These reductions were generally significant, and the association was removed completely when the dependent variable was suicidal intent in the past week. This suggests strongly that the effect of sexual abuse on suicidal behavior originates in its persistent effect on mood. It should be noted that affective state was assessed in relation to the week preceding the interview, postdating virtually all suicide attempts and experiences of sexual abuse. Thus, we used current affective state as a marker for a general propensity toward affective disturbance. Given the often fluctuant and repetitive nature of such disturbance, this is not unreasonable, and it is supported by the particularly strong effect of controlling for mood on the link between sexual abuse and suicidal intent in the week before the interview. Other investigators

(8,

9,

11,

28,

29) have found similar links among sexual abuse, gender, affect, and suicidality.

Methodological Limitations

The 2000 British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity provided information on a large and nationally representative nonclinical sample based on good methods of assessment, including standardized interviews performed by experienced and trained interviewers.

Although our findings are suggestive of a major effect of sexual abuse on suicidality in women, there are inevitable methodological problems with data from population surveys, such as the one used in our study. The data analyzed are based on participant self-report, and people may be reluctant to admit to both suicidal acts and experiences of sexual abuse. Respondents may also forget even notable events, although this may more likely occur with suicidal ideation than with actual suicide attempts. However, reportage failure would tend to attenuate the relationships found and thus act against our hypotheses.

Most of the reported suicide attempts in the present study occurred years before the survey (unpublished data available upon request from Bebbington et al.). Thus, there are inevitable difficulties in inferring the nature of the relationships apparent from our analysis. Respondents were only asked to relate their experiences of sexual abuse and of suicide attempts in relation to broad date categories. Sexual abuse is an event that may be repetitious, and it may indeed render victims vulnerable to later revictimization

(30,

31) . However, in most cases, the first episode is likely to occur early enough for it to precede the first suicide attempt

(31) .