The efficacy of antipsychotic drugs in preventing relapse in maintenance treatment for schizophrenia has been well established during the past half century (

1,

2). It has long been believed that antipsychotic doses can be reduced during the maintenance period (

3). In recent years, however, there have been suggestions (

4) that the initial therapeutic dose of antipsychotic drugs, particularly of atypical antipsychotics, should be maintained in the long-term treatment of schizophrenia, although evidence for this practice remains lacking.

We know of no systematic study that has focused on how long the initial therapeutic dose of a particular antipsychotic medication should be maintained following the acute phase of treatment. The

Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia (

5) suggests, "If the patient has achieved an adequate therapeutic response with minimal side effects or toxicity with a particular medication regimen, he or she should be monitored while taking the same medication and dose for the next 6 months." The

Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Schizophrenia in China (

6) recommends, "For a patient who has sufficiently responded to a particular antipsychotic medication, he or she should continue taking the same medication at the same dose for the next 3–6 months before a lower maintenance dose is considered for continued treatment." The authoritative Chinese psychiatric textbook (

7) recommends that "if a patient with schizophrenia has achieved an adequate therapeutic response, he or she should continue taking the same medication at the original therapeutic dose for the next 1 month before a lower maintenance dose is considered." However, these documents provide no solid evidence derived from randomized, controlled trials.

We set out to prospectively determine the length of maintenance treatment needed with the initial therapeutic dose, in contrast to a reduction to a lower dose, following stabilization of the acute phase in three groups of schizophrenia patients: 1) a 4-week group, for which the initial optimal therapeutic dose of risperidone was given for 4 weeks and then followed by a 50% dose reduction that was maintained until the end of the study; 2) a 26-week group, for which the initial optimal therapeutic dose of risperidone was given for 26 weeks and then followed by a 50% dose reduction until the end of the study; and 3) a no-dose-reduction group, for which the initial optimal therapeutic dose of risperidone was given throughout the study. On the basis of a previous meta-analysis that reaffirmed that long-term treatment with adequate antipsychotic doses was necessary in schizophrenia (

1), we hypothesized that the maintenance dose should be the same as the dose in the acute phase of the illness, i.e., patients in the no-dose-reduction group would have a lower relapse rate than the two groups for which lower doses were used in the maintenance phase.

Method

Study Participants and Settings

The study was conducted in 19 mental health centers nationwide, representing a range of clinical settings, from Dec. 1, 2002, to Jan. 31, 2005. The inclusion criteria were 1) age between 18 and 65 years; 2) either sex; 3) in- or outpatient status with a diagnosis of DSM-IV schizophrenia at study entry; 4) clinical stabilization following an acute episode for at least 4 weeks but less than 8 weeks, with "clinical stability" defined as a total score on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) of less than 36 points (

8) (acute episodes included all cases of hospitalization due to an exacerbation of psychotic symptoms [9]); 5) administration of risperidone monotherapy in an optimal therapeutic dose (4–8 mg/day) in the acute phase of treatment for the psychotic episode and response to antipsychotic treatment (i.e., being neither a partial responder nor refractory to antipsychotic treatment), as evidenced by a chart review and confirmed by the treating psychiatrist (the treating psychiatrists were not involved in the study design); 6) local residence with at least one family member after discharge; 7) satisfactory treatment adherence, defined by a pill count that yielded more than 80% adherence to the risperidone prescription over the past 4 weeks; and 8) an understanding of the aims of the study and a signed consent form. The exclusion criteria included 1) use of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, or Chinese herbal remedies concomitantly with risperidone or having received ECT or participated in any other drug trial or interventional study over the 4 weeks before study entry; 2) a history of or an ongoing major chronic medical or neurological condition; 3) past or current abuse of drugs or alcohol other than nicotine; and 4) pregnancy or plans to become pregnant, lactation, or lack of an effective method of birth control.

Procedures

Patients who met the study entry criteria were randomly assigned by a computer-based central telephone randomization system to the 4-week, 26-week, and no-dose-reduction groups (

10). Patients in the 4-week group were maintained with the initial therapeutic risperidone dose for 4 weeks, after which the dose was reduced gradually (0.5 mg every 7–10 days, depending on the starting dose) to one-half of the therapeutic dose over the next 8 weeks, which was maintained until the end of the study. Patients in the 26-week group kept the initial therapeutic risperidone dose for 26 weeks, after which it was gradually reduced (0.5 mg every 7–10 days, depending on the starting dose) to one-half over the next 8 weeks and maintained until the end of the study. In the no-dose-reduction group, patients received the full initial therapeutic risperidone dose throughout the study.

Zopiclone or zolpidem was allowed sparingly for insomnia, and trihexyphenidyl (maximum dose, 12 mg/day) and propranolol were given for the treatment of extrapyramidal side effects for any length of time. Other medications without CNS effects were also allowed for medical conditions.

Outcome Measures

The patients' sociodemographic data were collected with a questionnaire designed for the study. The primary outcome measure was relapse as defined according to the criteria of Csernansky et al. (

11). Whenever relapse occurred, the patient was withdrawn from the study and treated as clinically appropriate.

The secondary outcome measure was psychopathology as evaluated by the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity rating (

12) and the five factors of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale—Chinese version (PANSS-C) (

13): positive symptoms, negative symptoms, disorganized thoughts, excitement-hostility, and anxiety-depression (

11,

14–

18).

Patients who had not relapsed by the end of the study were divided into three groups: 1) those who improved over the course of the study, i.e., showed a 20% or greater improvement in the PANSS total score since study entry; 2) those whose condition deteriorated but who did not relapse, i.e., showed worsening of 20% or more in the PANSS total score since study entry; and 3) those who were between the preceding two groups and were considered stable, i.e., had a change in the PANSS total score from study entry within the range of –19% to +19%. For the statistical analysis, the patients were also divided according to the chronicity of their illness at entry. Patients whose illness had lasted longer than 5 years formed the high-chronicity group, and those with an illness duration of 5 years or less were assigned to the low-chronicity group (

19).

Adverse events were monitored with the Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale (

20), the Simpson-Angus Scale of Extrapyramidal Symptoms—Chinese version (

21), assessment of prolactin-related symptoms, full blood count, liver function tests (alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase), kidney function tests (BUN and creatinine), blood glucose measurement, ECG, and physical examinations. These were performed at baseline, 4–8 weeks after the dose reduction, and at the end of the study or at the time of relapse, discontinuation, or dropping out.

Course of Assessment

Before the study, all raters were trained in the use of the instruments and in judging relapse in 20 symptomatic schizophrenia patients. In the prestudy reliability exercise, the intraclass correlation coefficients for the scores on the PANSS, CGI severity item, Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale, and Simpson-Angus Scale of Extrapyramidal Symptoms ranged between 0.68 and 0.87. The raters' judgments of relapse were compared with the best-estimate clinical diagnoses; the kappa values ranged from 0.82 to 1.0. Whenever possible, the same raters evaluated the same group of patients throughout the trial.

Outcome measures were assessed monthly during the first 6 months and then every 2 months until the last enrolled patient completed the study. This meant that treatment for all patients continued until the last recruited patient completed his or her 1-year follow-up, i.e., the first patients enrolled were treated and followed up for 26 months. Patients were removed from the study if they suffered a relapse, became pregnant, acquired a severe medical condition, or suffered from newly emerging extrapyramidal side effects that they found intolerable.

Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the clinical research ethics committees of the respective study centers. Each participant signed a consent form.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, the actual relapse rate, the actual time from entry to relapse, and the three types of outcome (improvement, deterioration, and stability) at the end of the study in the three dose groups were compared by using analysis of variance and the chi-square test, as appropriate.

Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were used to calculate the estimated time from entry to relapse and the risk of relapse without control for covariates. The Cox proportional-hazards regression model was performed to compare the estimated times to relapse in the three groups with control for covariates, including risperidone dose at baseline, use of concomitant medications, study site, and medication adherence. The analyses included patients who relapsed and those who were lost to follow-up without documented relapse and were not considered relapsed at their last assessment. Study sites with 15 or fewer patients were grouped together according to their health care systems (

22).

Differences in the changes in the PANSS total score, scores on the five PANSS factors, and the CGI severity rating among the three groups from baseline to the end of the study were subjected to analysis of covariance with the baseline scores and risperidone doses as covariates. Adverse events among the three groups were compared with the chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, or analysis of covariance, as appropriate. The first 4-week period was considered separately because all patients received full therapeutic doses during that time. The continuous (secondary) outcome measures were subjected to last-observation-carried-forward analysis. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

Estimation of the required study group size was based on the results of a 1-year randomized trial that compared relapse rates between standard-dose and low-dose fluphenazine decanoate (14% versus 56%) (

23,

24). On the basis of a power of 0.9 and an alpha value of 0.025 (0.05/2), according to Cohen's method of power analysis (

25) the number of subjects in each group should be at least 26, and altogether at least 78 are needed. Taking into account the number of possible dropouts, we recruited 404 patients who met the study criteria.

Results

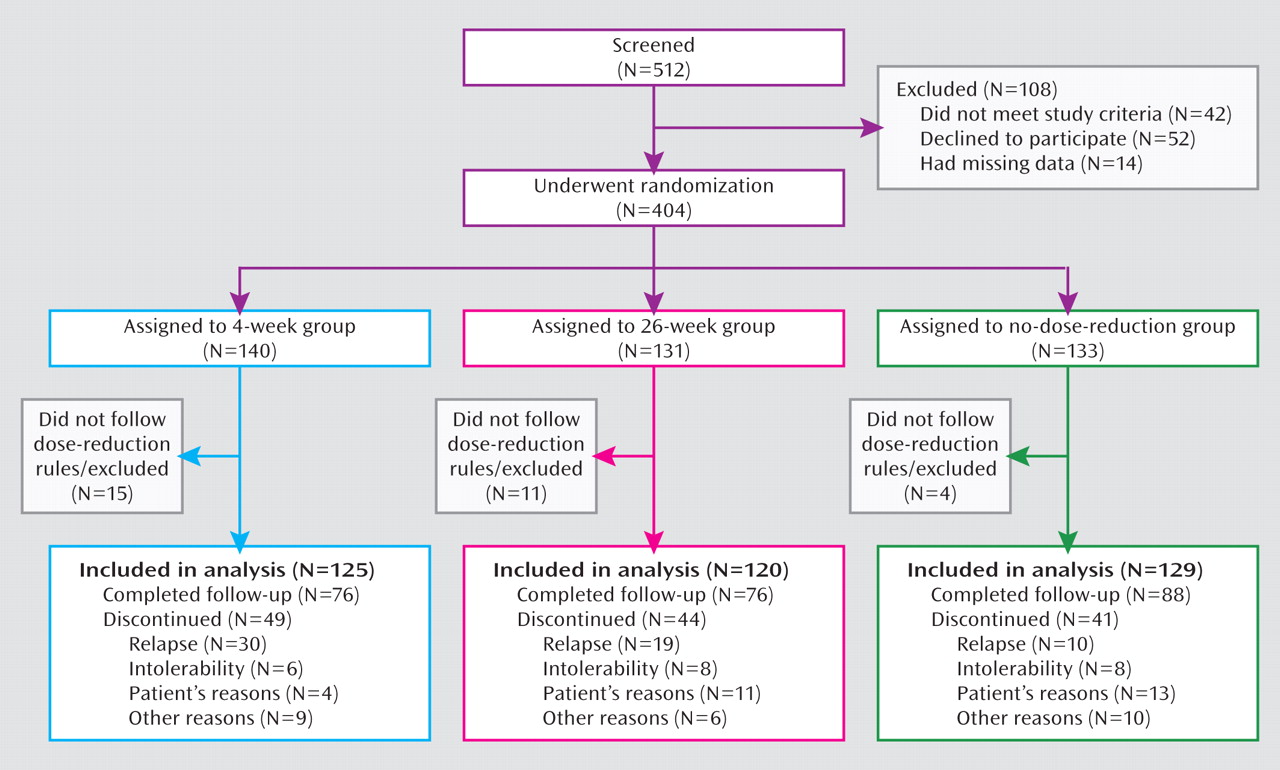

The 404 patients were randomly assigned to the three groups, but 30 patients were excluded from the study for not following the dose-reduction rules. Intention-to-treat analyses were performed with the 125, 120, and 129 patients in the 4-week, 26-week, and no-dose-reduction groups, respectively. A flow chart of the study is displayed in

Figure 1.

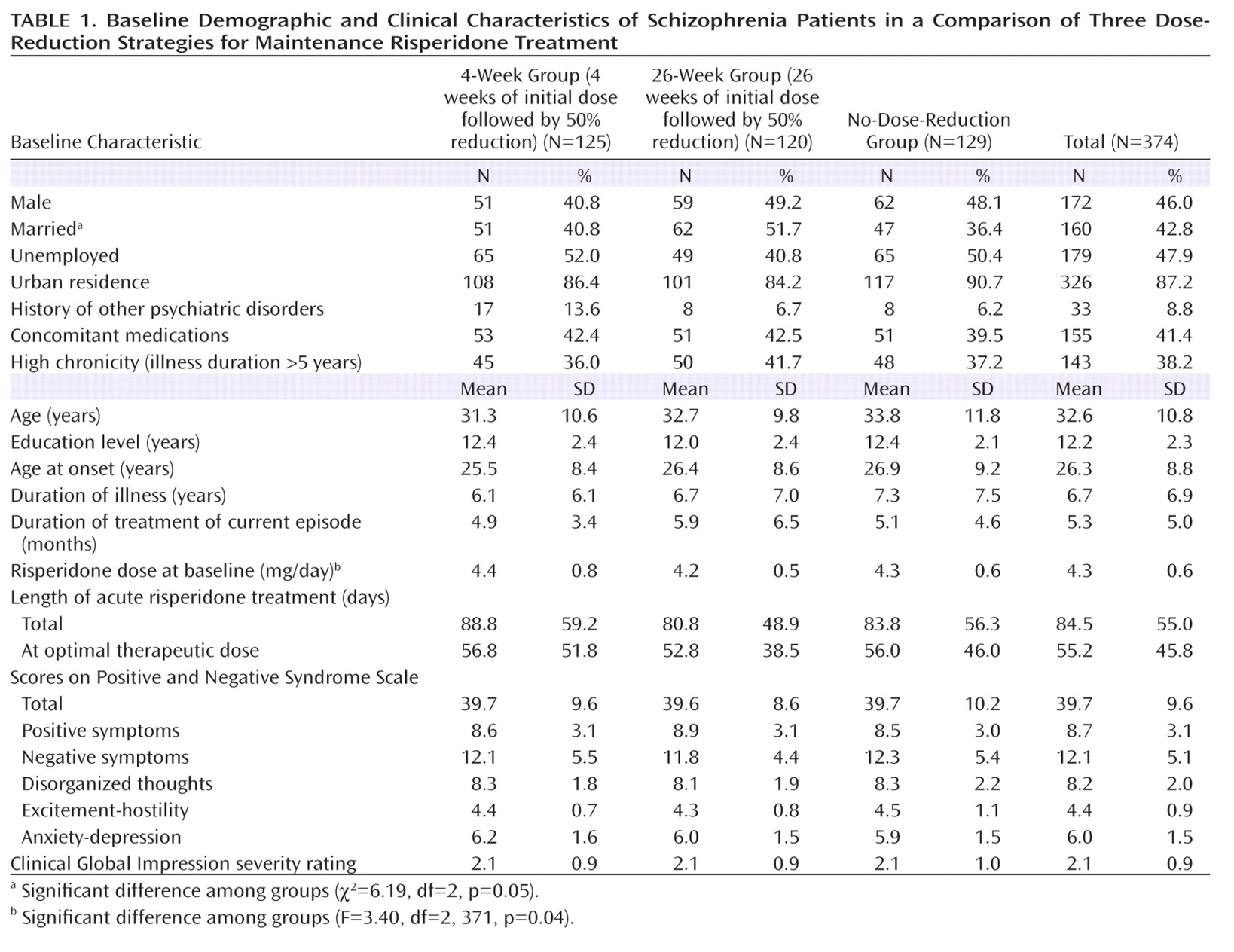

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

The participants' sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are shown in

Table 1. The only significant differences among the three groups were for marital status and the risperidone dose prescribed at baseline.

Withdrawal From the Study

The rate of premature discontinuation of treatment for any reason other than relapse did not significantly differ among the three groups: 15.2%, 20.8%, and 24.0% in the 4-week, 26-week, and no-dose-reduction groups, respectively (χ2=3.16, df=2, p=0.21). The reasons for early discontinuation across the three groups were similar (Figure 1).

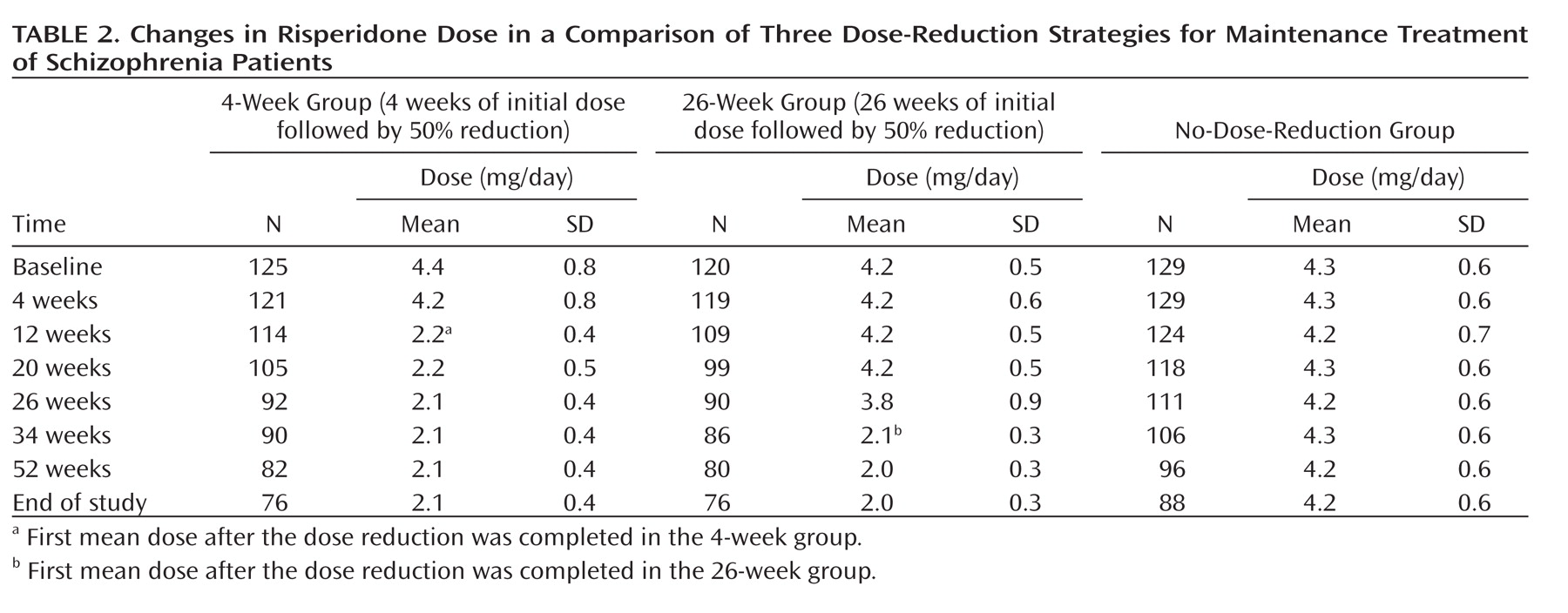

Dosage and Medication Adherence

Changes in risperidone dose over time are shown in

Table 2. Pill counts were used to measure treatment adherence; the percentages of pills taken were 97%, 92%, and 95% in the 4-week, 26-week, and no-dose-reduction groups, respectively.

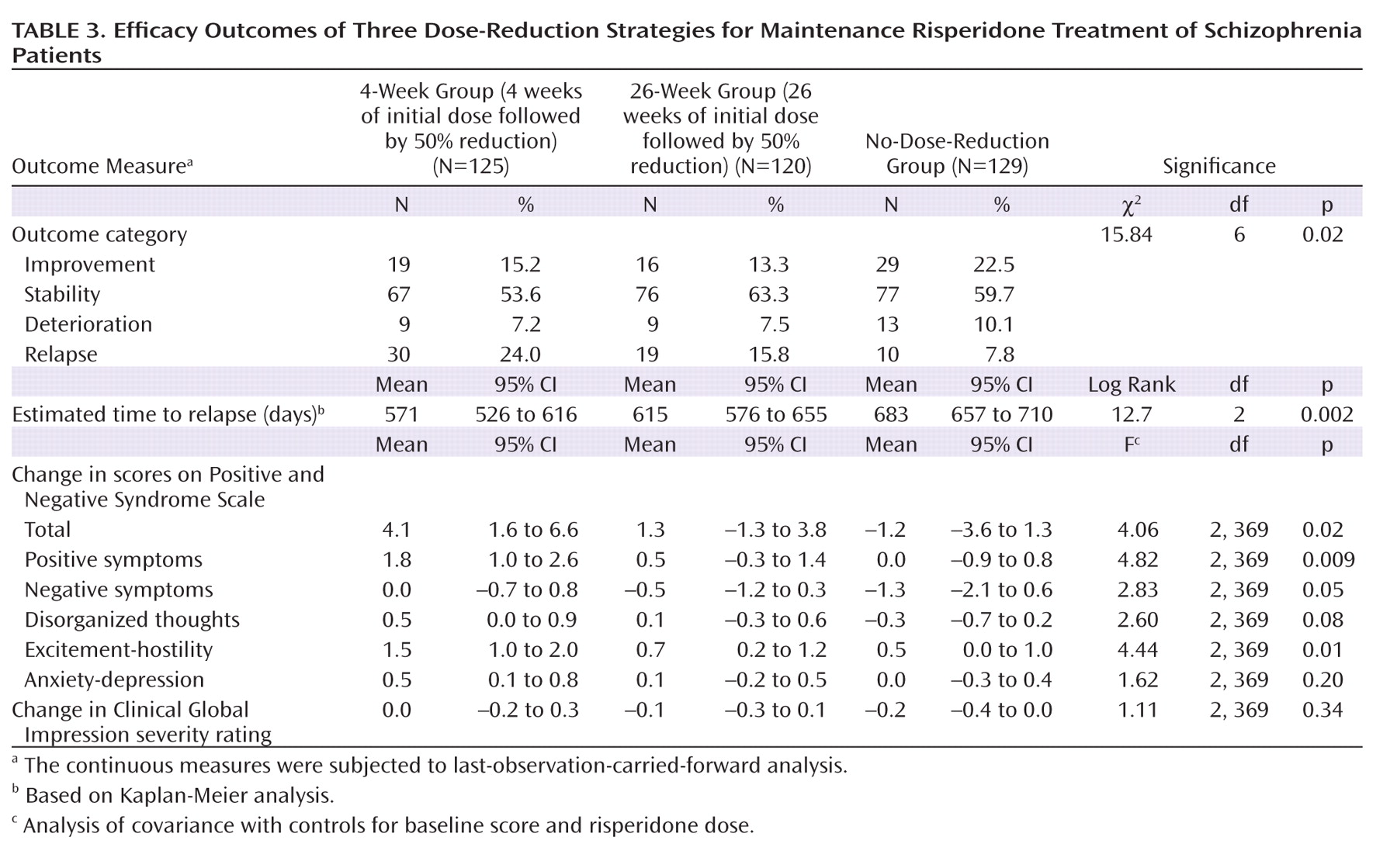

Relapse

The actual relapse rates were 15.8% in the whole study group and 24.0%, 15.8%, and 7.8% in the 4-week, 26-week, and no-dose-reduction groups, respectively (χ

2=12.61, df=2, p=0.002) (

Table 3). Patients in the no-dose-reduction group were less likely to have relapses than were those in the 4-week group (χ

2=12.63, df=1, p<0.001) and the 26-week group (χ

2=3.95, df=1, p=0.05), and there was no significant difference between the 4-week and 26-week groups (χ

2=2.56, df=1, p=0.11). The actual mean times to relapse (and 95% confidence interval [CI]) were 394 days (95% CI=357–431) in the 4-week group, 391 days (95% CI=353–428) in the 26-week group, and 442 days (95% CI=410–474) in the no-dose-reduction group. There was no significant difference among the three groups in the actual mean time to relapse (F=2.64, df=2, 371, p=0.07).

In order to explore the influence of illness chronicity on relapse prevention with therapeutic risperidone doses, multiple logistic regression analysis with the "Enter" method was used. The actual relapse was the dependent variable, while the independent variables were the three groups of patients and chronicity of illness with control for risperidone dose at baseline. Patients in the 4-week group were more likely to relapse than those in the no-dose-reduction group (β=1.35, df=1, p=0.001), but there were no differences between the 4-week and 26-week groups (β=0.56, df=1, p=0.09) and between the 26-week and no-dose-reduction groups (β=0.79, df=1, p=0.06). Chronicity of illness did not enter the final model (β=–0.24, df=1, p=0.42), suggesting that it had no significant influence on relapse prevention.

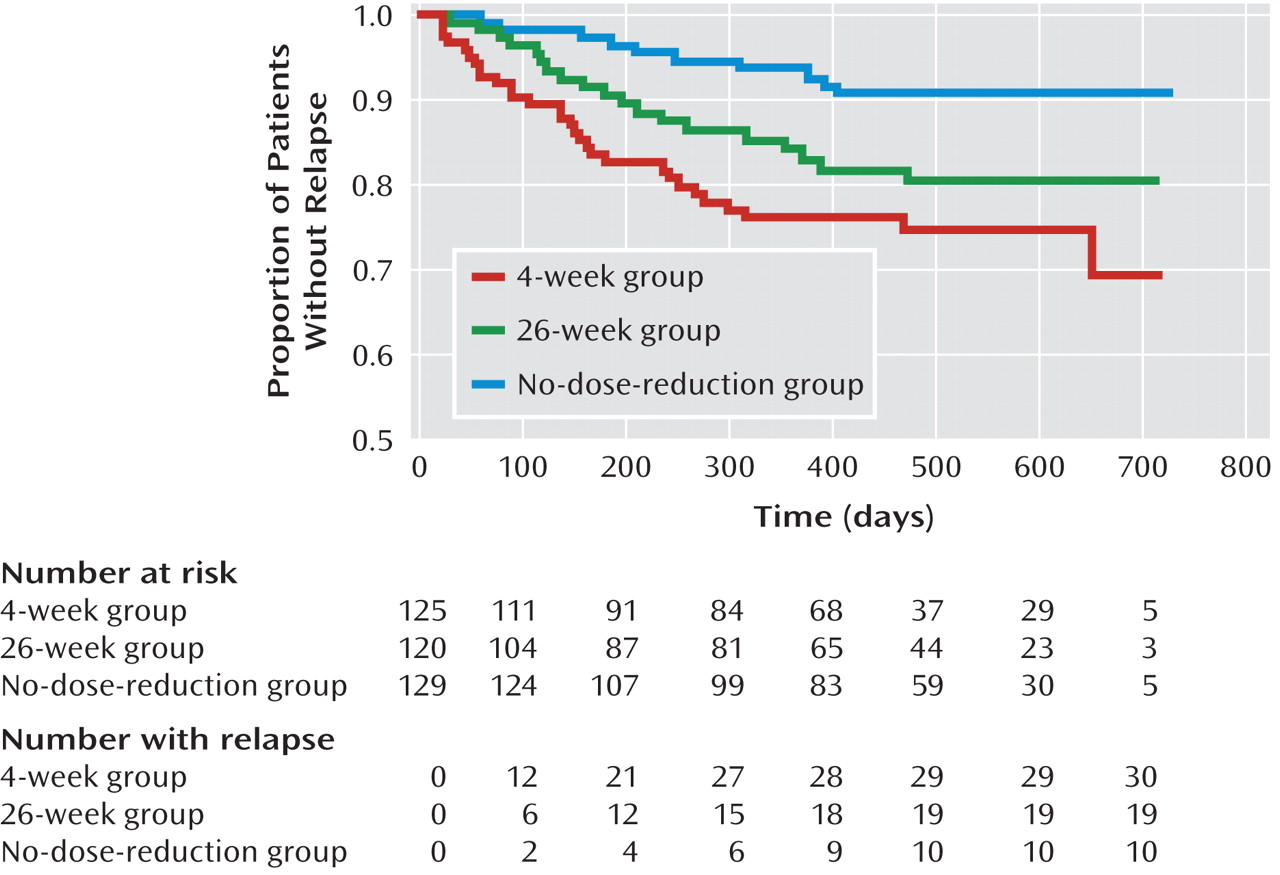

In the Kaplan-Meier analysis, the mean times to relapse were estimated. The intervals for the three groups are shown in

Figure 2 and Table 3; the difference among the survival curves is significant (log rank=12.7, df=2, p=0.002). In the pairwise comparisons, there were significant differences between the 4-week and no-dose-reduction groups (log rank=12.7, p<0.001) and between the 26-week and no-dose-reduction groups (log rank=4.8, p=0.03). The risk of relapse was 30.5% (95% CI=18.0%–43.0%) in the 4-week group, 19.5% (95% CI=11.5%–27.5%) in the 26-week group, and 9.4% (95% CI=3.7%–15.1%) in the no-dose-reduction group.

In the Cox model, the estimated mean time to relapse in the no-dose-reduction group was significantly longer than in the 4-week group (hazard ratio=3.43, 95% CI=1.67–7.01, p=0.001) and the 26-week group (hazard ratio=2.26, 95% CI=1.05–4.86, p=0.04), but there was no significant difference between the 4-week and 26-week groups (hazard ratio=1.52, 95% CI=0.85–2.69, p=0.16).

After control for the potentially confounding effects of risperidone dose at baseline, use of concomitant medications, study site, and medication adherence in the whole study group, the no-dose-reduction group continued to have an advantage in terms of time to relapse, relative to the 4-week group (hazard ratio=4.33, 95% CI=2.06–9.10, p<0.001) and 26-week group (hazard ratio=2.32, 95% CI=1.05–5.11, p=0.04).

Symptom Rating Scales

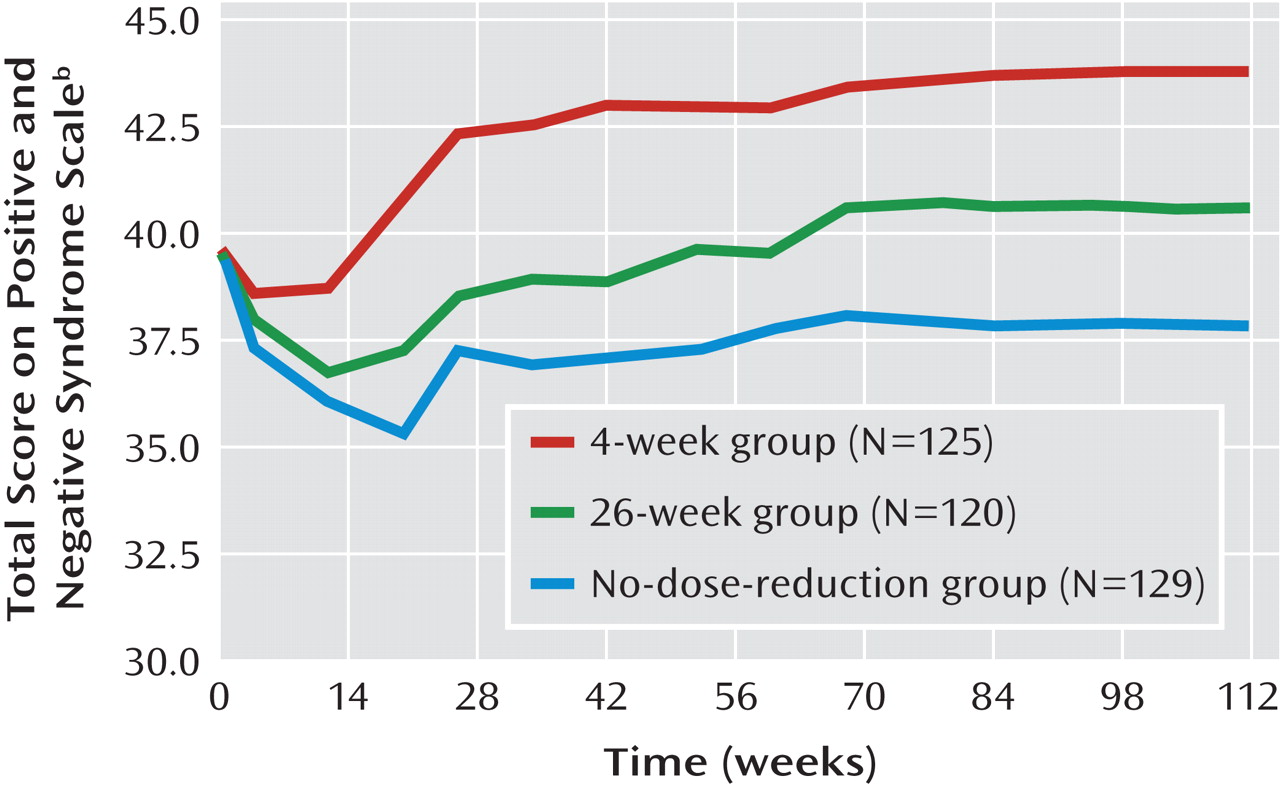

Psychotic symptoms, as measured by the PANSS over the study period, are shown in

Figure 3. Baseline scores on the PANSS and the CGI severity measure and their changes over time are presented in Tables 1 and 3. There were no significant differences at baseline among the three groups in the total score or subscores of the PANSS or the CGI severity rating. By the end of the study, changes in the PANSS total score and the scores on its subscales for positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and excitement-hostility became significant (p≤0.05). Table 3 also presents the outcomes of the patients in the three groups at the end of the study. There were more improved and stable patients in the no-dose-reduction group (82.2%) than in the 4-week group (68.8%) or the 26-week group (76.6%). The difference in outcomes among the three groups reached a significant level (χ

2=15.84, df=6, p=0.02).

All patients were followed up for at least 1 year, and so the three groups were compared with respect to the changes in the PANSS total score and the CGI severity score from baseline to 1-year follow-up by mixed-model analyses with no imputation of missing values (observed cases) after controls for baseline scores, baseline dose of risperidone, and study site. No significant differences among the three groups were observed in the change in the total PANSS score (F=2.40, df=2, 369, p=0.09) or the CGI severity score (F=0.24, df=2, 368, p=0.79) or in the interaction between group and time for the total PANSS score (F=0.64, df=18, 2801, p=0.87) or the CGI severity rating (F=0.42, df=18, 2795, p=0.98).

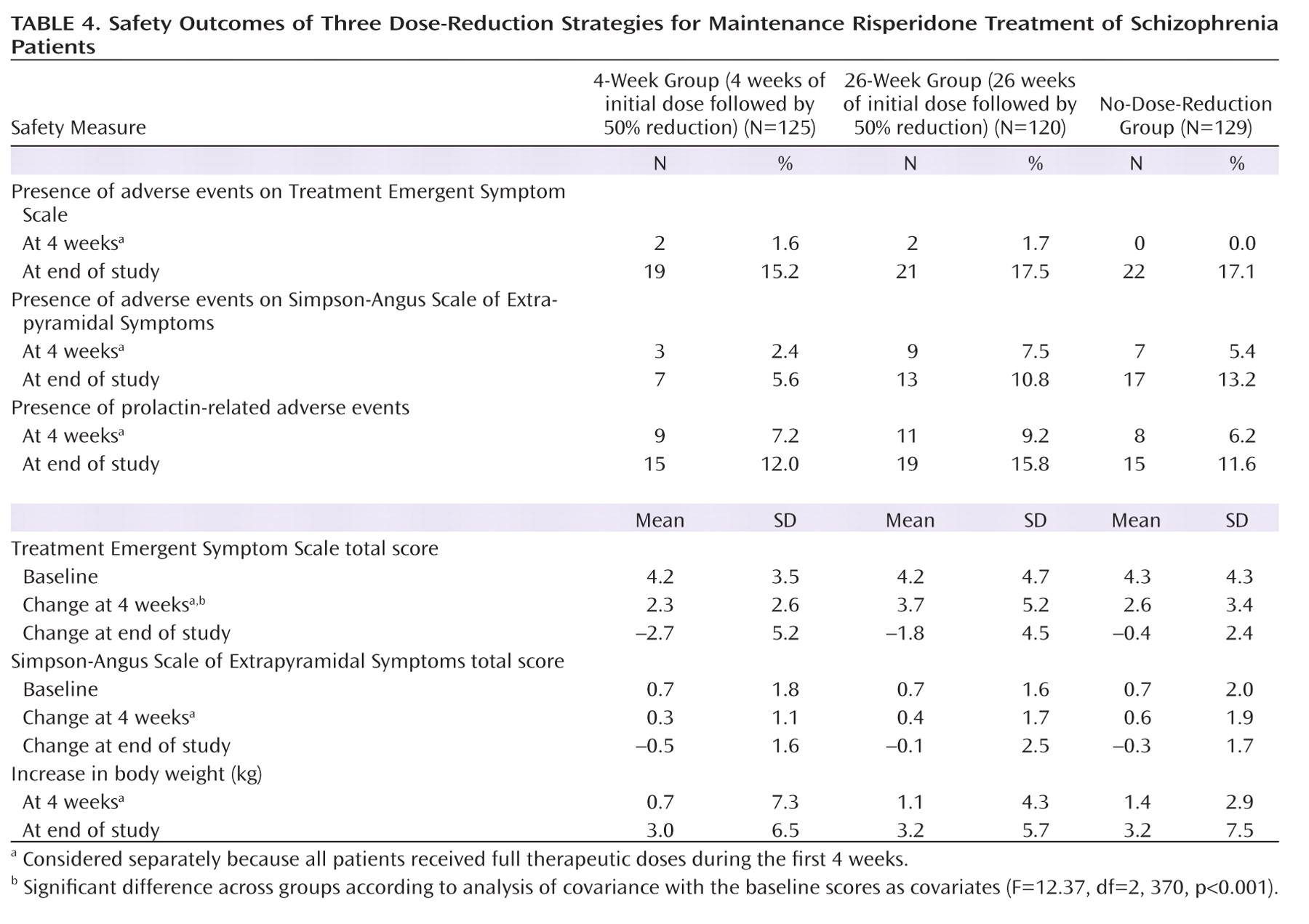

Extrapyramidal Side Effects and Other Adverse Events

The frequency of extrapyramidal side effects and other adverse events, scores on the Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale and Simpson-Angus Scale of Extrapyramidal Symptoms, and changes in body weight are shown in

Table 4. The proportions of extrapyramidal side effects and other adverse events did not significantly differ among the three groups at the end of the first 4 weeks or at the end of the study (p>0.05), and there were no significant differences in the baseline scores and changes from entry to the end of the study in the scores on the two scales or in body weight. There were no significant differences among the groups in changes on the Simpson-Angus scale score or in body weight during the first 4 weeks, while the increase in the score on the Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale for the 26-week group was significantly greater than for both the 4-week group (95% CI=0.90–2.15, p<0.001) and the no-dose-reduction group (95% CI=0.48–1.72, p=0.001).

There were no notable differences among the three groups with regard to vital signs, laboratory test results, or ECG findings.

Concomitant Psychotropic Medications

The frequencies with which the patients used any concomitant medications over the study period were 32.0% (40 of 125), 36.7% (44 of 120), and 43.4% (56 of 129) in the 4-week, 26-week, and no-dose-reduction groups, respectively. There was no significant difference among the three groups (χ2=3.57, df=2, p=0.17). Trihexyphenidyl was needed by 27.2% (N=34), 26.7% (N=32), and 33.3% (N=43) of patients in the 4-week, 26-week, and no-dose-reduction groups, respectively. The corresponding frequencies of patients receiving hypnotics were 9.6% (N=12), 17.5% (N=21), and 17.1% (N=22), whereas the figures for propranolol were 1.6% (N=2), 0.8% (N=1), and 6.2% (N=8).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically investigate the effect of the length of the therapeutic risperidone dose on relapse prevention by comparing three different durations of maintenance treatment.

In accordance with the currently prevailing view in Chinese psychiatry (

8,

26), clinical stability in patients entering this study was defined as a total score of less than 36 on the BPRS, a cutoff point that implies that patients can function well enough in every respect to be discharged. This cutoff point is higher than that recommended for Caucasian patients (

27), for whom BPRS scores of 31 and 41 correspond to "mildly ill" and "moderately ill" clinical status. The mean BPRS scores at entry into this study were 22.6 (SD=4.8), 22.7 (SD=4.5), and 22.7 (SD=4.7) in the 4-week, 26-week, and no-dose-reduction groups, respectively, indicating clinical stability even according to the criteria of Leucht et al. (

27). The difference between the cutoff points in Chinese and Caucasian patients may be due to discrepancies in clinical traditions and the sociocultural context.

Preliminary studies suggested that the therapeutic dose of risperidone should be between 2 and 4 mg/day for Chinese schizophrenia patients (

28,

29). The Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Schizophrenia in China (

6) recommend 2–6 mg/day as the therapeutic dose of risperidone for Chinese patients, a lower figure than the recommendation for their Caucasian counterparts (

30). Therefore, the mean risperidone dose (4.3 mg) used in the acute phase before study entry was sufficiently high according to Chinese standards.

Reduction in the dose of conventional antipsychotic drugs in the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia is justified as an attempt to reduce dose-dependent side effects (

31). The rationale underlying dose reduction for second-generation antipsychotics is less clear. In this study, the reduction in risperidone doses was in keeping with studies that have shown the optimal daily maintenance dose of this drug for Chinese schizophrenia patients to be 2–3 mg (

32–

34). Lower doses of risperidone are expected to mitigate the side effects related to weight gain and elevated prolactin levels (

35,

36).

The 4-week and 26-week groups were formed on the basis of the guidelines for the optimal length of original therapeutic doses in the stabilization phase for schizophrenia (

5,

7). The use of a no-dose-reduction group followed the updated treatment recommendation of the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) (

4). The therapeutic dose was reduced to half in the first two groups because it proved to be relatively safe in preventing relapse and reducing side effects compared to the more radical reductions tested in earlier studies, i.e., to 25%, 20%, and 10% of the therapeutic doses effective in the acute phase of the illness (

23,

31,

37–

39).

The actual relapse rates were 24.0%, 15.8%, and 7.8% in the 4-week, 26-week, and no-dose-reduction groups, respectively. Except for the favorable relapse rate in the no-dose-reduction group, the other two are in the range of the rates for schizophrenia patients receiving risperidone (12%–25%) found in earlier studies (

11,

40,

41). In this study, our hypothesis was supported by the finding that the no-dose-reduction group was associated with the lowest relapse risk, followed by the 26-week and 4-week groups, and there was also a significantly longer estimated time to relapse for the no-dose-reduction group than for the other two groups. This advantage for the no-dose-reduction group in the estimated time to relapse remained even after the covariates were controlled, supporting the notion that the maintenance dose for risperidone should be the dose found to be effective in the acute phase of treatment (

4). We cannot compare these results with earlier findings because we know of no similar published study.

First-episode schizophrenia patients require lower doses because they are more sensitive to the pharmacologic effects of antipsychotics than are chronically ill patients (

42,

43). In view of this finding, multiple logistic regression analysis was performed with the assumption that chronicity of illness would significantly influence relapse prevention. This hypothesis was not supported by the results.

Psychotic symptoms were better controlled at the end of the study in the no-dose-reduction group than in the two other groups. There were more patients judged to be improved or stable in the no-dose-reduction group. No significant differences were observed in terms of side effects or adverse events among the three groups, indicating that superior relapse prevention with the therapeutic doses used in the acute phase was not linked to a higher risk of drug-induced side effects. Risperidone is associated with weight gain and increased prolactin level (

35,

36). Confirming these associations (

35,

36), the weight gains in this study were 3.0, 3.2, and 3.2 kg, and the frequencies of prolactin-related adverse events were 12.0%, 15.8%, and 11.6% in the 4-week, 26-week, and no-dose-reduction groups, respectively. No significant differences were observed in the three groups in terms of weight gain or frequency of prolactin-related adverse events.

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution because of certain methodological limitations. First, the open-label design of the study may have influenced the assessment of psychopathology and side effects to an unknown degree. However, the lack of significant differences among the three groups with regard to the frequency and severity of extrapyramidal side effects and other adverse events at the end of the study suggests that these biases were probably minimal. Second, the possibility that a higher dose of risperidone could have been associated with an even lower relapse rate cannot be excluded. This is unlikely, however, because the actual relapse rate of the maintenance group with no dose reduction (7.8%) compares favorably with the results of similar studies. Third, the results are not applicable to other antipsychotic drugs. Fourth, the patients' reasons for discontinuation were not recorded. Fifth, although there are several pathways to meeting the relapse criteria of Csernansky et al. (

11), the characteristics of those pathways were not recorded and analyzed. Finally, an exploration of the association between initial doses and relapse would have been of interest, particularly a determination of whether a 50% reduction of high initial therapeutic doses (6–8 mg/day) could be well tolerated and effective. However, as there were only 11 patients in the two dose-reduction groups with initial daily doses of 6–8 mg, no statistical analysis could be performed.

Acknowledgments

The following institutions and investigators participated in the trial: Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University—Chuan-Yue Wang; Beijing Huilongguan Hospital—Cheng-Jun Ji; Department of Psychiatry, Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical College—Xiu-Feng Xu; Department of Psychiatry, Renmin Hospital, Wuhan University—Gao-Hua Wang; Department of Psychiatry, First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing University of Medical Sciences—Hua-Qing Meng; Department of Psychiatry, First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiao Tong University—Cheng-Ge Gao; Foshan Third Hospital—Wen Deng; Fuzhou Psychiatric Hospital—Jia-Wu Ji; Guangzhou Brain Hospital—He-Huang Deng; Hebei Provincial Mental Health Center—Ke-Qing Li; Institute of Mental Health, Peking University—Hong-Yan Zhang; Jilin Provincial Mental Health Hospital—Fang Cai; Mental Health Institute of the Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University—Tie-Qiao Liu; Nanjing Brain Hospital—Jian-Xiong Fan; Shanghai Mental Health Center—Shi-Min Weng; Shenyang Mental Health Center—Xiu-Zhen Wang; Suzhou Guangji Hospital—Ming Li; Seventh People's Hospital of Dalian—Hong-Yu Fan; Tianjin Anding Hospital—Yi Wang.

The authors thank Mr. Tony Leung for his assistance in data analysis.