Ever since Lombroso (

1) proposed a brain basis to the controversial concept of "the born criminal" in the 19th century, the identification of the very early neurobiological and medical processes that give rise to adult criminal offending has been elusive. With some exceptions (

2), the majority of studies of very young children have focused on psychosocial influences, with relatively little attention to early neurobiological influences (

3–

6). In this article, we suggest that poor fear conditioning is one of the early neurobiological risk factors that predispose some individuals to adult criminal offending.

Poor autonomic fear conditioning has been shown to be a well-replicated correlate of adult criminal and psychopathic adult offending (

7–

9). Individuals are hypothesized to learn to avoid antisocial and criminal acts by successfully associating stimuli that are associated with antisocial events with later socializing punishments (

8–

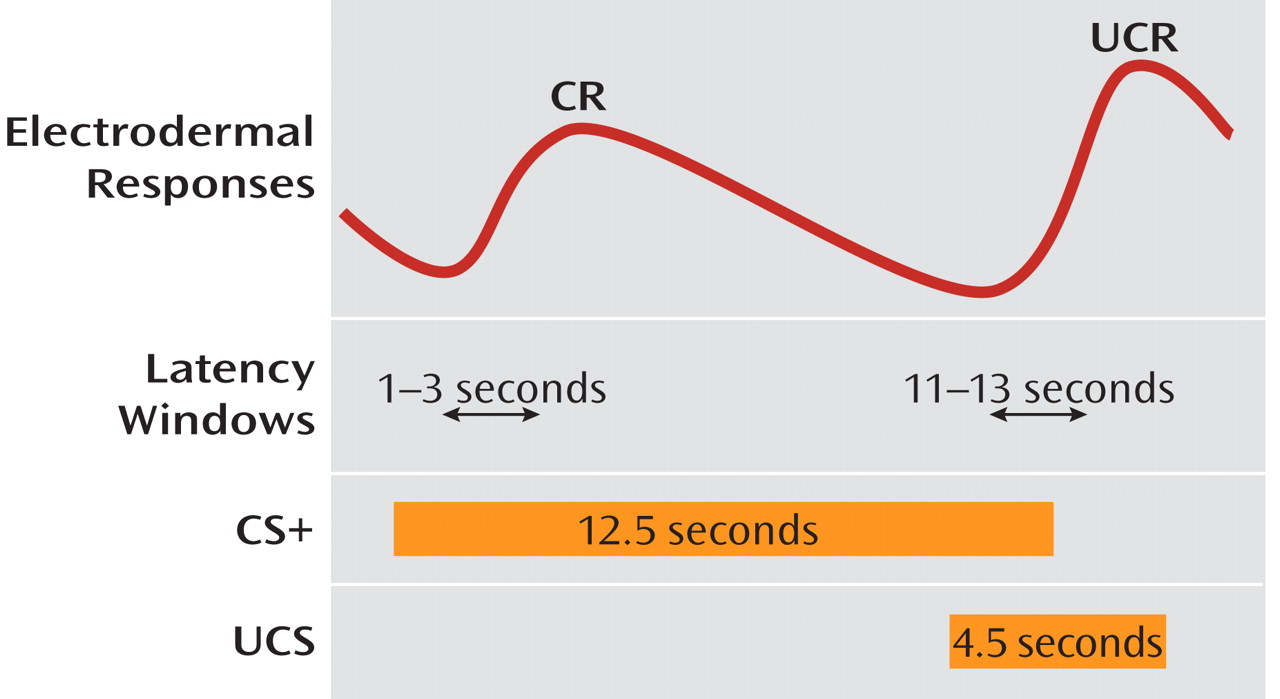

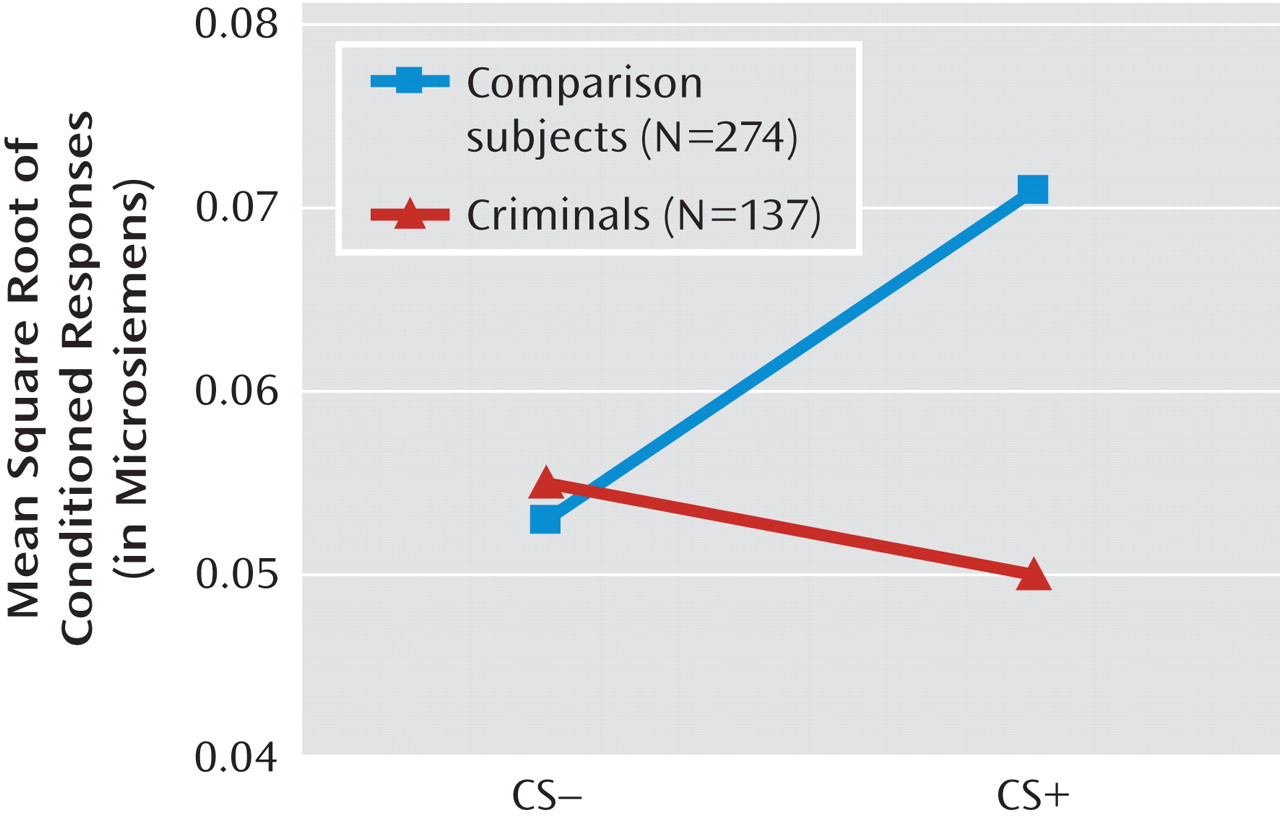

11). This association learning is hypothesized to result in an increase in anxiety and anticipatory fear whenever the individual contemplates the commission of an antisocial act, which in turn motivates the individual to avoid such stimuli and the commission of antisocial, rule-breaking behavior. Within this framework, poor conditionability, as measured by reduced responsivity to the reinforced conditioned stimulus (CS+) followed by the aversive stimuli (UCS), compared to a control stimulus not followed by an aversive event (CS–), may give rise to criminal acts in some individuals.

Both imaging and lesion studies have indicated that the amygdala is critically involved in fear conditioning (

12), and clinical neuroscience research in adults has increasingly provided evidence for the primacy of amygdala dysfunction in some antisocial populations (

10,

13–

15). Similarly, the ventral prefrontal cortex (including the orbitofrontal cortex) plays a role in fear conditioning and the representation of information on aversive outcomes and has been found to be dysfunctional in antisocial populations (

10,

15). Nevertheless, an unsolved issue in the absence of brain imaging data in very young children concerns whether poor fear conditioning, a proxy for amygdala dysfunction, occurs early in life in those on a pathway to a criminal career. In this study, we addressed this question by measuring classically conditioned emotional responses at age 3 in a birth cohort of 1,795 children and following them up after 20 years to assess outcome for criminal convictions at age 23. It was hypothesized that compared to the noncriminals, criminal offenders at age 23 would show reduced fear conditioning at age 3.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to demonstrate an early deficit in autonomic fear conditioning as a predisposition to adult criminality. The findings are consistent with the hypothesis that poor amygdala functioning early in life, as indicated by poor fear conditioning, increases the risk for criminal offending (

22), and they demonstrate that this fear conditioning risk factor for crime is in place early in life and is not explained by social adversity, ethnicity, or gender. Poor fear conditioning is hypothesized to predispose to crime because individuals who lack fear are less likely to avoid situations, contexts, and events that are associated with future punishment—resulting in a lack of conscience (

8). The findings of this study are broadly consistent with a neurodevelopmental perspective on criminal offending.

Dysfunction in multiple brain structures, with a focus on frontal-temporal regions, has been implicated in criminal offending. Imaging studies have repeatedly reported antisocial-related impairments in orbitofrontal, dorsolateral, and limbic systems, including the amygdala, the insula, and the anterior cingulate cortex (

15,

23,

24). The circuitry involved in fear conditioning is similarly complex, involving the orbitofrontal cortex, the insula, and the anterior cingulate in addition to the amygdala (

12). Provisional brain imaging findings in adult offenders are beginning to document dysfunction in these other brain regions involved in fear conditioning (

13). The amygdala, which is viewed as the primary structure subserving fear conditioning, is found to be less activated when psychopathic offenders contemplate a moral decision (

25). Similarly, amygdala hyporesponsiveness has been reported in children with callous-unemotional traits (

26,

27), although some neuroimaging and genetic studies (e.g., monoamine oxidase A polymorphism) suggest that there may be quite different neurobiological abnormalities in subgroups of antisocial individuals, particularly those with increased emotional reactivity (

28–

30). Furthermore, reduced connectivity between the amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex may conceivably underlie the fear conditioning impairments in criminals rather than localized dysfunction to one or the other of these brain regions (

27). We hypothesize that, taken together with the findings of this study, deficits in related brain regions give rise to both poor fear conditioning and behavior problems and that the circuitry involved in fear conditioning is compromised in early childhood in a subgroup of individuals who evidence criminal behavior in adulthood.

The findings of this study potentially provide some support for a neurodevelopmental theory of antisocial and criminal behavior (

31). Cavum septum pellucidum, a marker of limbic neural maldevelopment, has been associated with higher levels of antisocial personality, psychopathy, and arrests and convictions in a community sample (A. Raine et al., unpublished 2009 manuscript), and minor physical anomalies (markers for fetal neural maldevelopment at the beginning of the second trimester of gestation) have been found to be more common in delinquents and criminals (

32,

33). Child and adolescent imaging studies also provide some limited initial support for the neurodevelopmental perspective. Gray matter abnormalities in the frontal-temporal areas, including reduced volume in the left amygdala, have been found in children and adolescents with conduct disorder (

34,

35). Adolescents with conduct disorder also show reduced amygdala responsiveness to negative emotional stimuli compared to age-matched comparison subjects (

36). While atypical amygdala structure and function have been observed in children with conduct problems, to our knowledge no imaging studies on conduct problems have been conducted in children under age 11. Unlike some other brain regions (e.g., the polar prefrontal and temporal cortices), the amygdala is rarely susceptible to illness and injury (

37), and hence amygdala dysfunction may be more likely to have an early neurodevelopmental basis. Only when it becomes possible to conduct brain scans in large samples of very young children and follow them longitudinally over several decades will it be possible to confirm early amygdala dysfunction as a specific source of poor fear conditioning in young children who become adult criminal offenders.

If crime is in part neurodevelopmentally determined, efforts to prevent and treat this worldwide behavior problem will increasingly rely on early health interventions. Prenatal programs aimed at health factors, including reducing cigarette, alcohol, and drug consumption and improving nutrition, have led to significant reductions in juvenile delinquency 15 years later (

38). Enhancing the early health environment of young children from ages 3 to 5 years with better nutrition, more physical exercise, and cognitive stimulation has been shown both to improve brain functioning 6 years later, as indicated by a reduction in slow-wave EEG power (indicating faster developmental brain maturation), and to reduce adult criminal offending by 35% (

18); conceivably it could also improve amygdala functioning. Such programs applied early in life and combining multidisciplinary health services from clinical, social, and educational domains have the potential to improve brain functioning and to make a public health contribution to the reduction of criminal offending throughout the world. At the same time, due caution should be exercised in the application of neurobiological markers early in life to predict later offending; crime is clearly a complex construct involving multiple interactions between genetic, brain, family, and societal influences (

31) and cannot be predicted by single neurobiological markers such as fear conditioning.