The introduction and definition of bulimia nervosa were presented only 30 years ago. In his salient publication, Gerald Russell

(1) emphasized the dread of overeating, various compensatory measures, and the morbid fear of gaining weight and getting fat. Within this relatively short period of time, a remarkably large number of outcome studies have been published. Early reviews included one review based on eight studies

(2) and another on 24 follow-up studies

(3) . The latter found a mean recovery rate of 47.5% and mean rates of 26% for both improvement and chronicity. Shortly before the turn of the century, Keel and Mitchell

(4) analyzed the course of 56 patient series and found a recovery rate of 50% and chronicity in 20% of the patients. The mortality rate of 0.3% was slightly lower than that reported in the prior review of 24 studies

(3) . The review by Vaz

(5) concentrated on prognostic factors only, and Quadflieg and Fichter

(6) reviewed various outcome measures in a total of 33 studies. Finally, a recent, more selective review based on very rigorous inclusion criteria by Berkman et al.

(7) provided findings from 13 patient series. Steinhausen’s analysis

(8) of the outcome of anorexia nervosa in the second half of the last century served as a model for the present review.

Method

Selection criteria for the inclusion of studies in the present review were 1) data on at least one out of five outcome measures for bulimia nervosa after a minimum follow-up evaluation period of 6 months following the treatment episode and/or 2) data on any prognostic factor of the disorder. The aforementioned reviews consisted of a total of 141 studies. A systematic search with various databases was performed using the terms “bulimia nervosa,” “outcome,” “follow-up,” and “prognosis.” A search using PubMed led to an additional 60 studies, and a search using PsycINFO resulted in 19 studies. Thus, before applying any exclusion criteria, a total of 220 published studies were available. As a result of duplicate or review-type studies, 68 studies were excluded. Furthermore, 26 studies did not include sufficient information on the duration of follow-up evaluation or provided pre-post measures only or were based only on follow-up periods <6 months. In another 21 studies, information on the course of the disorder was insufficient (e.g., no information on sample size or no independent assessment of anorexia and bulimia nervosa patients was provided). Finally, there were 14 studies dealing with prognostic factors only, and another 12 studies presented additional data based on the same patient cohort. Thus, at the end, a total of 79 patient series were entered into the analyses for the outcome of bulimia nervosa in the present review. Findings were published between 1981 and 2007. Data based on reports from a total of 32 studies were extracted by the expert senior author. Decisions on the inclusion of the remaining studies were jointly made by both the junior and senior authors.

Study Characteristics

The 79 published reports

(9 –

87) were composed of 5,653 patients (group mean size=71.6 [SD=113.4], range=4–884). There were considerable differences in design, group size, methods, duration of follow-up evaluation, and missing data. Diagnostic classification changed considerably over the period in which the studies were conducted. Since the 1990s, there has been an increasing reliance on DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria. In 46 studies consisting of 2,508 patients, the mean age at onset was 17.2 years (SD=1.7, range=4.3–23.2), and the mean age at follow-up assessment was 28.4 years (SD=4.3, range=16.6–38.0) in 39 studies consisting of 2,478 patients. The mean duration of follow-up evaluation varied between 6 months and 12.5 years (mean=3.2 months [SD=3.3]) in 77 studies of 5,239 patients. In 66 studies of 3,830 patients, a total of 75 men (1.9%) were included.

A minority of studies used combined intervention and follow-up evaluation, whereas the majority of studies used only limited evaluation of treatment effects. The available information on treatment was classified as 1) nonbehavioral psychotherapy, 2) unspecified medical intervention, 3) cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), 4) family intervention, or 5) mixed or uncontrolled intervention.

In the analyses for prognostic factors, 35 studies included information on prognostic factors in addition to data on outcome

(10,

14,

15,

17,

21,

24,

25,

30,

34 –

36,

40 –

44,

52,

54,

55,

57,

61,

63,

65,

68,

71 –

73,

75,

76,

83,

88 –

92), and 14 studies

(93 –

106) dealt exclusively with prognostic factors. The total sample of these studies on prognosis consisted of 4,639 patients (mean=94.62 [SD=133.76], range=4–884).

Outcome Measures

The five central outcome criteria for the present analyses were recovery, improvement, chronicity, mortality, and crossover to other eating disorders. In addition, information on comorbid mental disorders was collected. Information on recovery was provided in the studies as part of 1) a three-level classification in combination with improvement and chronicity, 2) a two-level classification mostly in combination with chronicity, or 3) a single criterion. There were 22 synonyms of recovery (e.g., “abstinent”). Improvement was most commonly used as a medium category of a three-level classification. In a few instances, rates of improvement were reported in combination with recovery only. Among the 27 synonyms of improvement were terms such as “intermediate course,” “some remaining symptoms,” or “partial remission.” Finally, among 21 synonyms of chronicity, the most common were “bulimia nervosa,” and “poor course.” Some studies used crossover to another eating disorder according to DSM-IV criteria as an outcome category in addition to recovery and chronicity. All mortality rates represented crude mortality rates. None of the studies reported standardized mortality rates.

Statistical Analyses

The five outcome measures were calculated in percentages that were rounded to the nearest whole value. In order to take into account the large variation in sample sizes, weighted percentages were calculated by weighting each reported rate with the size of the study group. Data for all studies were converted into individual data for performance of statistical analyses using SPSS 14 (SPSS, Chicago).

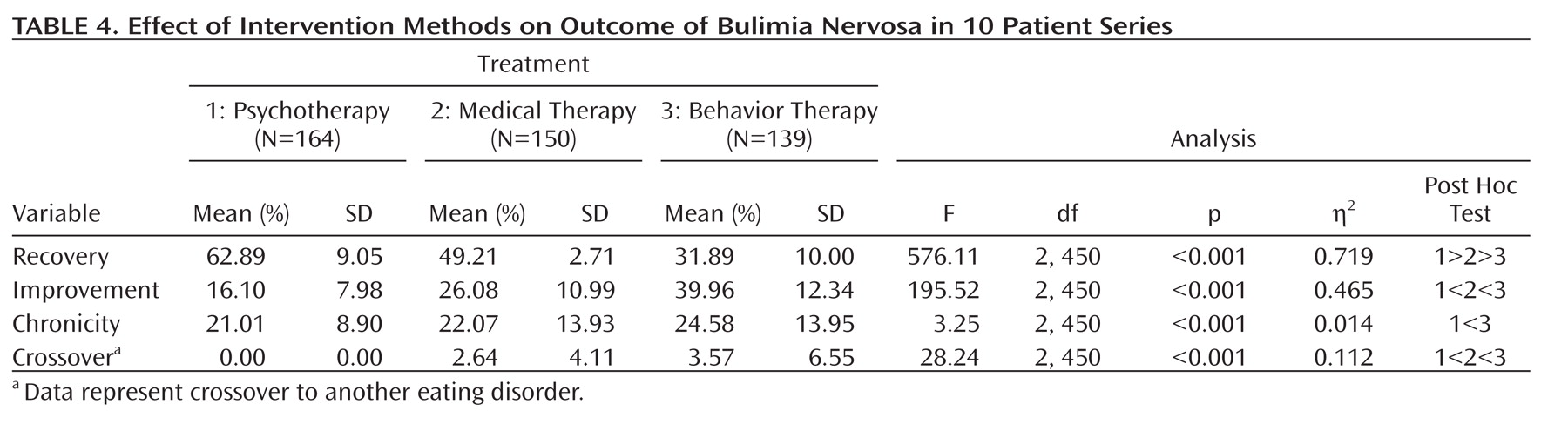

All analyses were based on adjusted sample sizes at follow-up assessments rather than actual sample sizes after patient recruitment. Differences between these two figures were considered the dropout rate. The latter was dichotomized into high (≥16% of the original sample) and low (0%–15% of the original sample) categories and served as a first independent effect variable. In accordance with previous analyses

(8), the duration of follow-up evaluations was the second independent effect variable and categorized as <4 years, 4 to 9 years, or ≥10 years. Studies with a variable length of course were not considered for analyses of effect. In case there was more than one report based on the same cohort, only the last report with the longest duration of follow-up assessment was considered for the analyses. The third independent variable was represented by the type of intervention. Because of limited data, the aforementioned classification of available information on treatment into five types was restricted to the following three types: nonbehavioral psychotherapy, unspecified medical therapy, and CBT.

Effects of these three variables for treatment type on four outcome measures were analyzed using multivariate analyses of variance. In addition, effect sizes were calculated using partial eta-squared (η

2 ) as a measure of association between independent and dependent variables. According to Cohen

(107), η

2 =0.01–0.059 represents a small effect, η

2 =0.06–0.13 represents a median effect, and there is a large effect starting with η

2 =0.14. Furthermore, the frequencies of positive, negative, and insignificant prognostic factors were calculated.

Discussion

Similar to the previous extended review by Steinhausen

(8) on the course and outcome of anorexia nervosa, the present review on the course and outcome of bulimia nervosa was based on the largest database currently available and was not confined to descriptive statistics, which was the case in most prior reviews. Using methods of inferential statistics, an attempt was also made to isolate factors that might have influenced the course of bulimia nervosa. Findings were based on a large group of 5,653 patients on whom data were published in little more than one-quarter of a century. In the Steinhausen review, a similar number of patients suffering from anorexia nervosa (N=5,590) was studied within one-half a century. Thus, the intensity of studying the outcome of bulimia nervosa has been very strong. Furthermore, it has to be noted that the present review was based on published data on patients who had been seen predominantly by expert groups. However, as long as there are no reports from other sources, such as community physicians, it is impossible to conclude whether or not the present findings are biased as a result of patient selection.

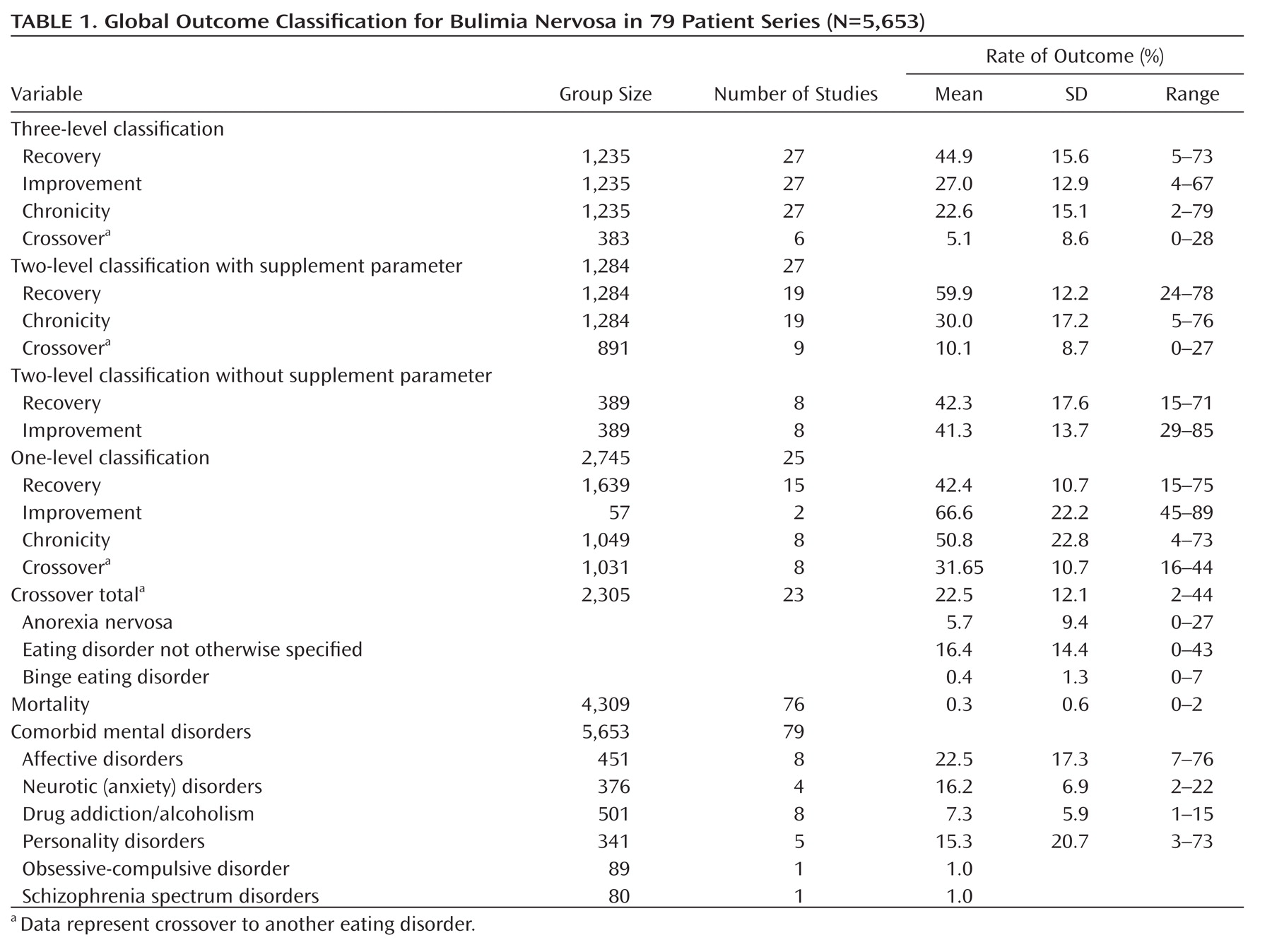

The discussion of the main outcome findings was severely hampered by a lack of commonly accepted outcome criteria. Different three- and two-level classifications or single criteria for the outcome of bulimia nervosa were presented in the literature. Given the wide acceptance of the distinction among recovery, improvement, and chronicity as classification of the global outcome of diseases in general, and in the previous review by Steinhausen on the course of anorexia nervosa in particular

(8), findings based on this classification should be considered those with the highest face value. Within this scheme, findings on mean recovery rates for bulimia nervosa (45%) and anorexia nervosa (46%)

(8) were remarkably similar. In addition, the mean improvement rates (bulimia nervosa, 27%, versus anorexia nervosa, 33%) and mean chronicity rates (bulimia nervosa, 23%, versus anorexia nervosa, 20%) were not extremely different in these two largest reviews. However, it needs to be mentioned that, first, these figures represented only a central tendency, and there was a large variation across studies in both reviews. Second, the different criteria of outcome on the course of bulimia nervosa in the studies add to the uncertainty of the data. Thus, studies relying on other schemes of classification resulted in higher or similar mean rates of recovery or higher mean rates of improvement and chronicity. There is no meta-analytical strategy to overcome these different findings because they are rooted in basic differences of the studies.

According to the present review, crossover to other eating disorders in the course of bulimia nervosa is very common. However, as a result of differences in the design of the outcome criteria of the studies, it was difficult to identify precisely the mean rate of crossover diagnoses, which was between a 10% and 32% range, depending on the criteria for the outcome. Obviously, the most common crossover at follow-up evaluations was to eating disorder not otherwise specified, followed by anorexia nervosa, and the least common crossover was to binge eating disorder. However, the low rate of binge eating disorder may be partially the result of underreporting because the term was not yet introduced when many of the older outcome studies were performed.

With a mean crude mortality rate of 0.32%, including a number of deaths not caused by bulimia nervosa, bulimia nervosa was definitely less fatal than anorexia nervosa, which resulted in a mean crude mortality rate of 5% in the review by Steinhausen

(8) . However, the frequencies of comorbid psychiatric disorders were high for both disorders. Affective and neurotic/anxiety disorders ranked highest, and there was a sizable proportion of patients with personality disorders at follow-up evaluations. Although the crude figures for comorbid disorders were higher for anorexia nervosa, these differences should not be overestimated because many studies did not clearly indicate the criteria for assessment or diagnosis.

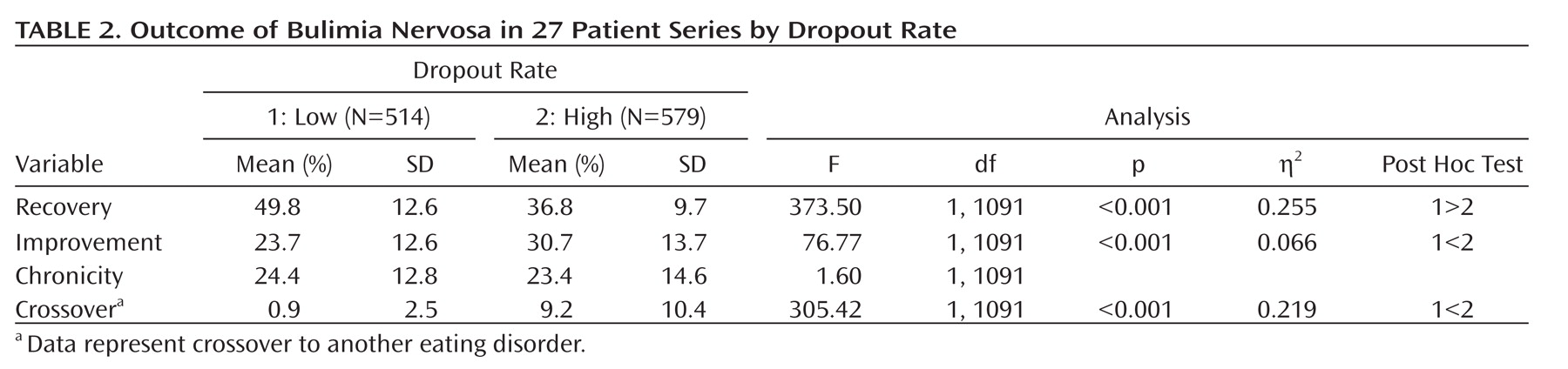

Several conclusions may be drawn from the present analyses of three central variables (dropout rate, duration of follow-up evaluation, and type of intervention) with an effect on outcome. First, there is some evidence that, perhaps counter to expectation, patients who dropped out of follow-up studies may have had a more favorable course of bulimia nervosa. Staying in the follow-up cohort may reflect patients’ continuous need for further treatment. Thus, one might argue that the outcome of representative samples of patients without sample loss may be more favorable than delineated from the present data.

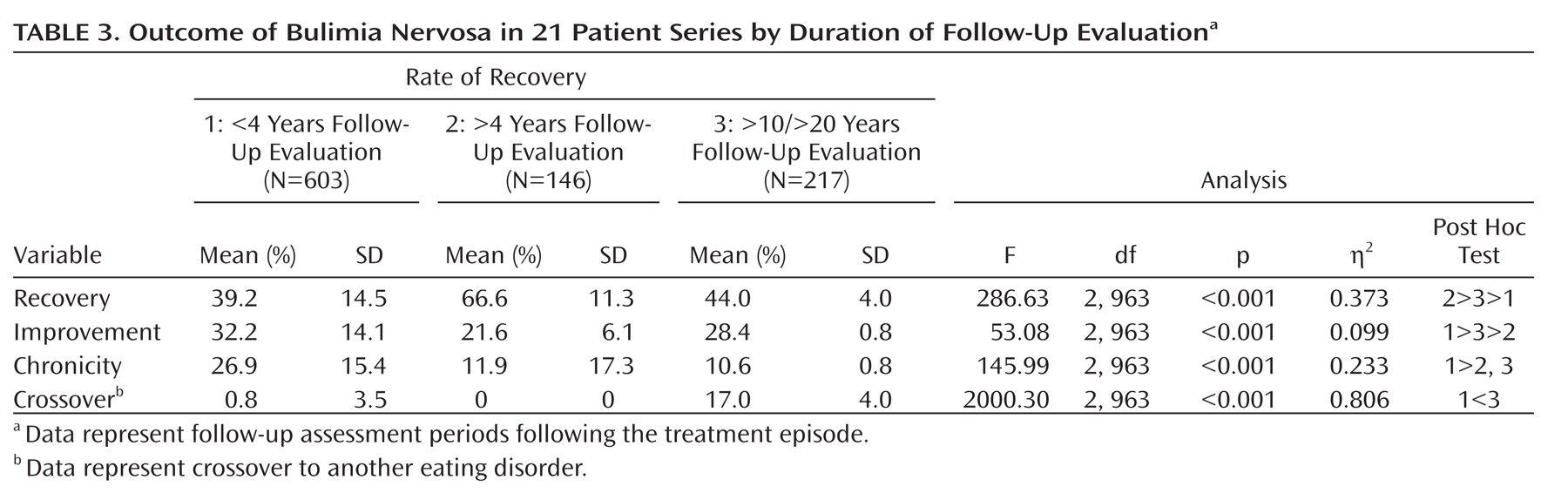

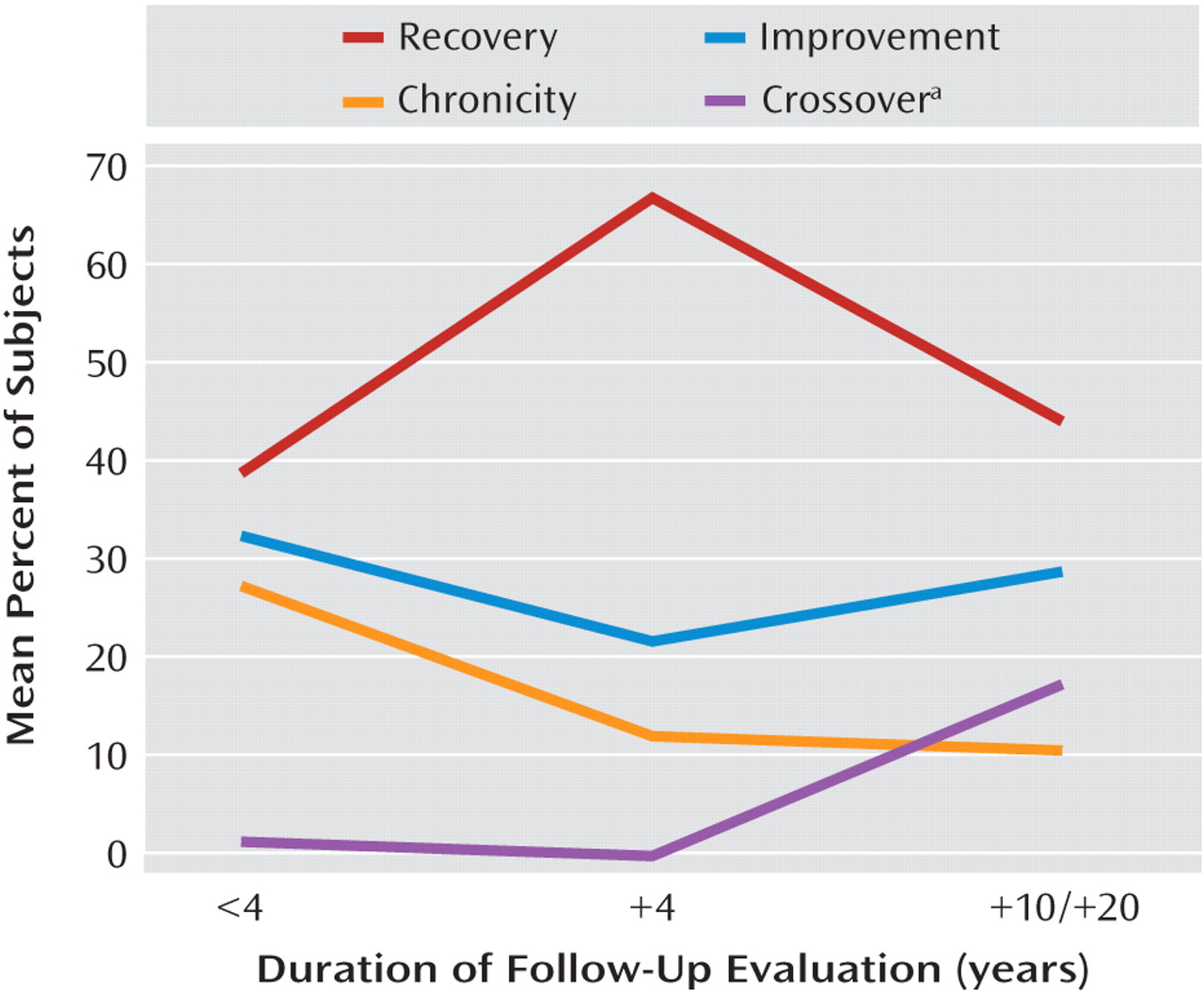

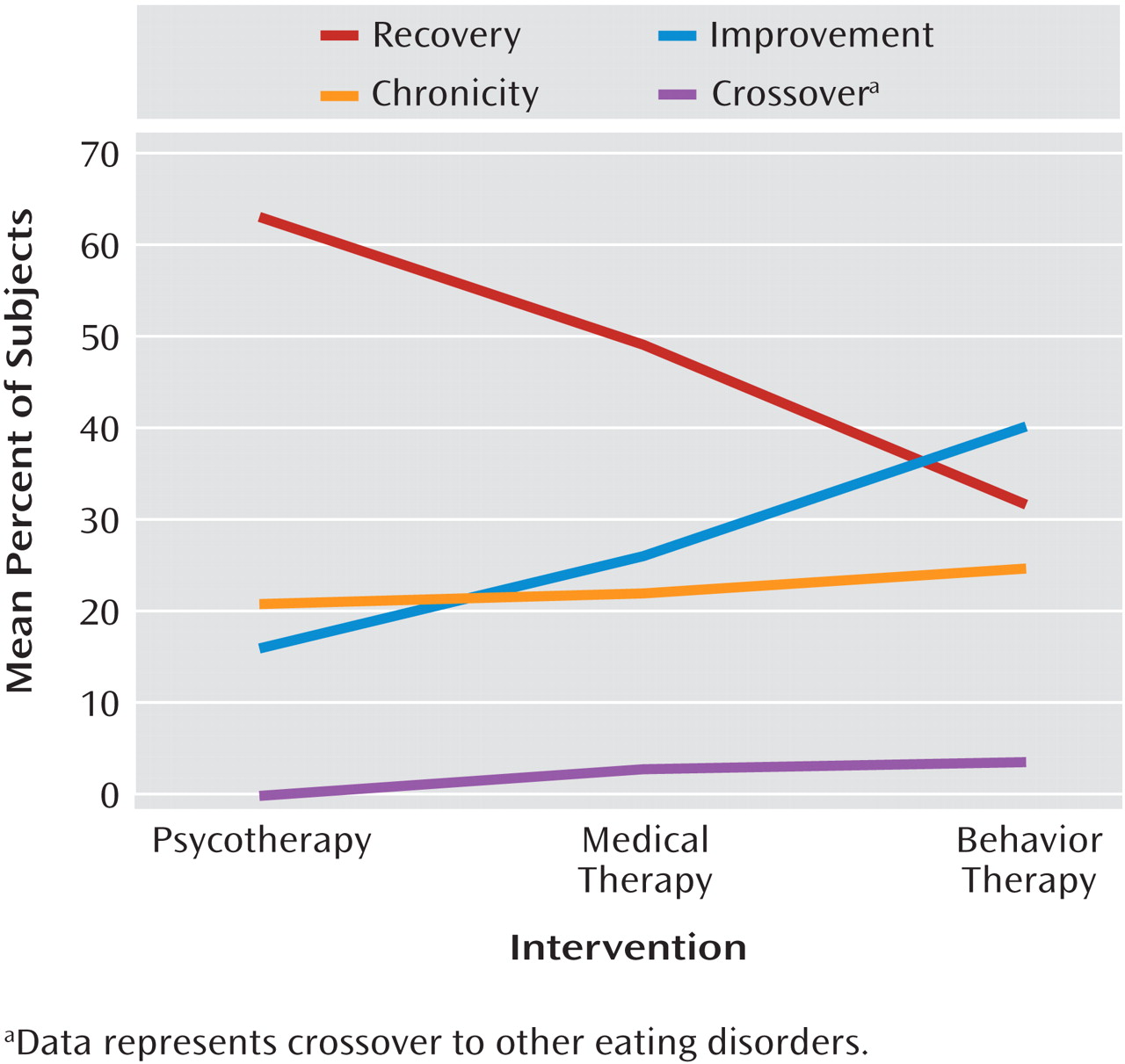

Second, duration of follow-up evaluation was the variable with the strongest effect on outcome. The distribution of data did not allow for a more fine-grained analysis, particularly for ≤4 years of follow-up evaluation. The profiles shown in

Figure 1 clearly indicate a curvilinear course of bulimia nervosa, particularly if one considers the curve representing crossover diagnoses to be a part of the chronic course of illness. It is also obvious that the mean recovery rate peaked in the 4- to 9-year follow-up interval and declined thereafter, whereas the rates for chronicity and crossover followed the reverse pattern and the rates of improvement remained relatively stable across time. According to these data, the developmental trajectory of bulimia nervosa in the present analyses was rather different from the course of anorexia nervosa in the previous review by Steinhausen

(8), which showed a linear relationship indicating better outcome with increasing duration of follow-up evaluation. However, it needs to be taken into consideration that these data were derived from a composition of cross-sectional samples only. The few larger longitudinal bulimia nervosa outcome studies with repeated assessments over extended follow-up periods tended to show a more favorable course with increasing duration of follow-up evaluation

(34,

42) . However, these findings may not be representative because they were based on patients who had been treated in expert centers.

Third, both the analyses of effect variables and of intervention studies allow for conclusions on the role of treatment for bulimia nervosa. This is in contrast to the studies on anorexia nervosa, which included a paucity of facts on the effect of interventions on outcome

(8) . In the entire data set of studies in the present analyses, there were strong effects indicating a clear superiority of psychotherapy over medical therapy and behavior therapy. However, this finding was overshadowed by a lack of clear description of the type and modalities of treatment employed in the various studies. Furthermore, as a result of methodological shortcomings and/or contradictory findings, intervention studies provided only limited evidence regarding which treatments actually may contribute to a positive outcome. Standards of intervention studies, such as controlled randomization or a waiting comparison group analysis, are almost entirely missing in the literature because of problems with clinical practicality. At least for CBT, there is some limited evidence that it may contribute to more favorable outcomes for bulimia nervosa. Clearly, this field is in need of more sophisticated research.

Finally, there was a large number of studies dealing with prognostic factors in various domains. Despite the considerable effort that was invested in this area of research, the majority of these factors did not prove to have any significant effect on the disorder. Only a few of the significant factors were replicated, and many studies resulted in contradictory findings. Information on prediction models, excluded variables, or nonsignificant factors was mostly missing in the reports. Most frequently, prognostic factors were seen in isolation. In the outcome literature on anorexia nervosa, it was shown that favorable, unfavorable, or nonsignificant prognostic factors may be extracted from the various study reports

(8) . However, multivariate analyses with consideration of a large group of factors in a large sample of patients with anorexia nervosa have clearly shown that very few variables actually have an effect on outcome if their covariation is considered

(109) . Thus, most of the findings on prognostic factors of bulimia nervosa must be considered as insufficiently controlled. Certainly, this field also is in need of further refinement of research. From the existing literature, a concentration on treatment factors seems most promising. However, one has to consider the likely nature of study data that preclude any delineation of rules for individual prognosis for a given patient.

In conclusion, the present comprehensive review of one-quarter of a century of outcome research shows that bulimia nervosa remains a serious disorder with unsatisfactory recovery and improvement rates and high rates of patients who continue to have chronic eating disorder problems and other comorbid psychiatric disorders over extended periods of their lives. Future research efforts could benefit from more collaborative and prospective studies based on large unselected samples and standardized assessment procedures using a common set of operationalized criteria of outcome. Refined study designs should particularly focus on the role of intervention in the long-term outcome of the disorder so that research might also identify beneficial effects on the course of the individual patient.