Epidemiologic and observational clinical studies have evaluated the effects of biological, social, and psychological factors on the risk of suicide (

2,

3). In addition, several studies have reported that air pollution can decrease psychological well-being and neuropsychological functioning, contributing to increased psychiatric admissions and emergencies (

4,

5). However, the association between air pollution and suicide has not been evaluated.

In this study, we determined the association between short-term exposure to ambient particulate matter and the risk of suicide using a time-stratified case-crossover study design.

Method

Study Subjects

Data on suicides that occurred in seven metropolitan cities (Seoul, Busan, Incheon, Daejeon, Daegu, Gwangju, and Ulsan) in 2004 were obtained from the Death Statistics Database of the National Statistical Office, and postmortem examination data were obtained from the National Police Agency. A total of 4,341 suicide cases were included in this study.

To determine the medical conditions of study subjects, medical care utilization data from the year preceding death were obtained from the Health Insurance Review Agency. All legal residents of the Republic of Korea are covered by the Korea National Health Insurance program, and their medical care utilization, including disease codes (ICD-10-CM), prescriptions, and treatment procedures, is reviewed by the Health Insurance Review Agency. We evaluated five disease groups as underlying diseases: cardiovascular disease (I10–I15, I20–I25, and I60–I69), diabetes mellitus (E10–E16), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease including asthma (J40–J47), cancer (C00–C97), and psychiatric illness (C10–C33). The subject's health insurance premium, which is based on family income and immovable property, was used as a proxy measure of socioeconomic status. Individual premiums were categorized into quintiles according to premium statistics for all Koreans. Beneficiaries of the Medical Aid program were categorized as the lowest quintile.

Air Pollution and Meteorological Data

Hourly mean concentrations of particulate matter ≤10 μm in aerodynamic diameter (10-μm particulate matter) were measured at 106 outdoor monitoring sites in 2004 (Seoul, 34 sites; Busan, 19 sites; Incheon, 14 sites; Daejeon, 6 sites; Daegu, 13 sites; Gwangju, 6 sites; and Ulsan, 14 sites). Hourly mean concentrations of particulate matter ≤2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter (2.5-μm particulate matter) were measured at 13 sites in Seoul. City-specific mean concentrations of 10-μm particulate matter and 2.5-μm particulate matter were calculated, and 24-hour mean concentrations were used for analysis. All particulate matter data were provided by the Ministry of Environment and the Seoul Metropolitan Government. Meteorological data on temperature, dew point temperature, relative humidity, air pressure, and hours of sunlight were obtained from the National Meteorological Office. The mean daily concentrations of particulate matter and meteorological variables are summarized in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article.

Statistical Analyses

The association between particulate matter and suicide was evaluated with a time-stratified case-crossover study design in which the stratum was defined as the month of the event. The case period for each suicidal death was defined as the confirmed date of death. In case of death on arrival at the hospital or death during hospital treatment, the date of emergency care visit or hospital admission was used. The same days of the week as the case period within the same month (e.g., Mondays) were selected as the control periods, thus allowing three or four control days per case day. Because subjects served as their own controls, cross-subject differences were controlled by study design (

11).

A two-stage hierarchical model was used to assess the association between particulate matter and the risk of suicide. In the first stage, we applied conditional logistic regression analysis (PROC PHREG), using SAS, version 9.1, to estimate the effect of particulate matter on suicide risk in each city (

12), and the single- or cumulative-lag model to estimate the effect of particulate matter. Variables included national holidays, mean hours of sunlight from the previous 2 days, and cubic splines of meteorological factors: the temperature (df=6), the mean temperature of the 3 previous days (df=6), the dew point temperature (df=3), the mean dew point temperature of the previous 3 days (df=3), the air pressure (df=3), and the mean air pressure of the previous 3 days (df=3) (

13). In the single-lag model, we estimated the effect of particulate matter on one day only: the day of suicide or 1, 2, or 3 days prior to the day of suicide (described as lag 0, lag 1, lag 2, and lag 3, respectively). In the cumulative-lag model, the effect of particulate matter was estimated on the specified day and all subsequent days (e.g., cumulative lag 2 used the mean particulate matter concentrations of lag 0, lag 1, and lag 2). Particulate matter concentrations were fitted into the model as continuous variables. Effect estimates were expressed as the percent change in suicide risk associated with an interquartile range increase in 24-hour mean particulate matter concentration (27.59 μg/m

3 increase in 10-μm particulate matter and 18.20 μg/m

3 increase in 2.5-μm particulate matter).

In the second stage, the random-effects metaregression model (PROC MIXED) was used to estimate the overall effect (described as the random-effects estimate) across all cities using the estimates from the city-specific models of the first stage in order to account for city variability and allow for generalizability beyond the cities included in the study (

8,

9,

12). In addition, data from all suicides were pooled to determine the association between particulate matter and suicide. However, 2.5-μm particulate matter was measured in one city only; therefore, only conditional logistic regression analysis was conducted for those data.

During the study period, data were 100% complete for the hourly 10-μm particulate matter and 95.7% complete for the 2.5-μm particulate matter. Missing values for 2.5-μm particulate matter were imputed using the multiple imputation method (

14); we first generated five copies of the original data set, and each missing value was replaced with a value generated by the imputation model (PROC MI). After performing identical conditional logistic regressions on each data set, the results were combined to produce overall estimates and standard errors (PROC MIANALYZE) (

12).

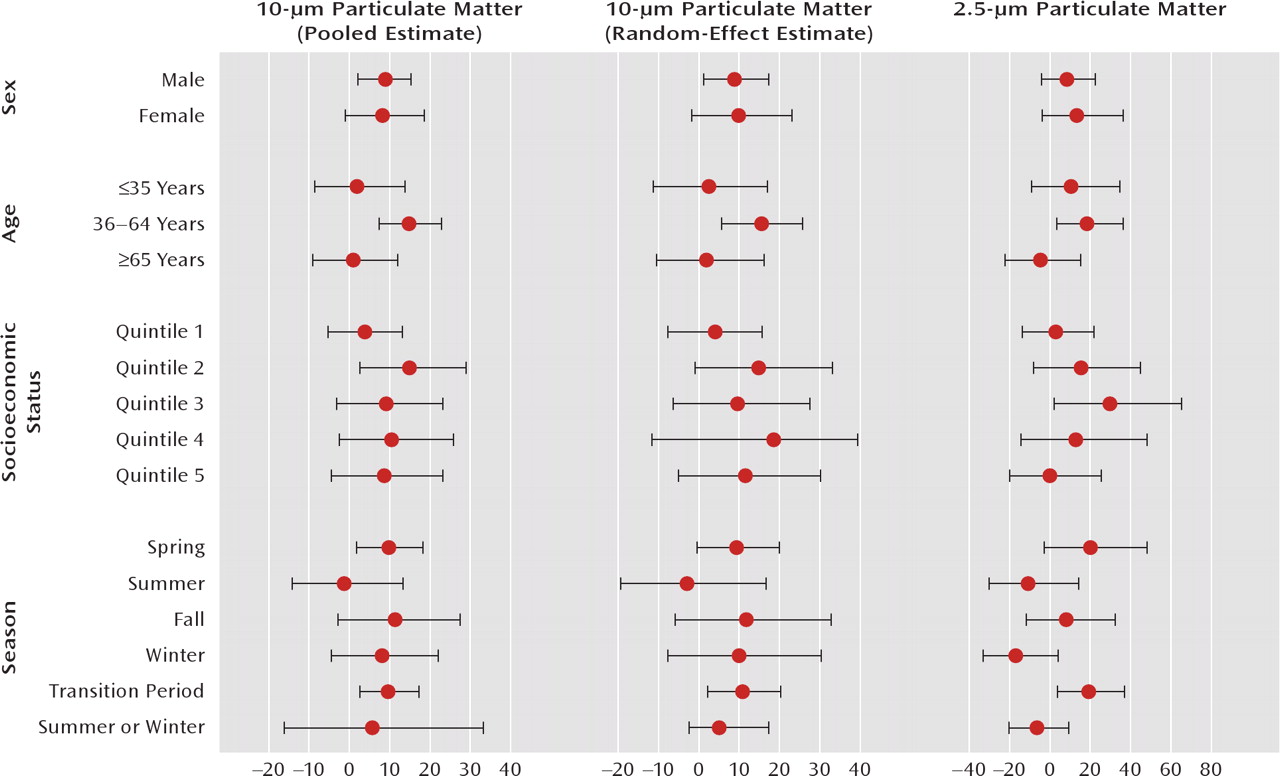

Variability in the effects of particulate matter on suicide could be attributed to differences in epidemiologic characteristics. Analyses were performed using the cumulative-lag 2 model after stratifying separately by sex, age group (≤35 years, 36–64 years, and ≥65 years), season of death (spring, summer, fall, or winter), underlying diseases (cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and psychiatric illness), and socioeconomic status (quintiles of individual insurance premiums). In addition, because deaths associated with particulate matter were higher during seasonal transition periods (spring or fall) compared with summer and winter (

15), the season of death was further categorized into two groups: summer/winter and seasonal transition periods. To reduce the chances of missing important associations during the early stage of analysis, we used a statistical significance level of 5% with no correction for multiple comparisons. We determined statistically significant differences between effect estimates across strata of a potential effect modifier (e.g., the difference between males and females) by calculating 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (

16). All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Health System, Seoul. The authors used randomly generated identification numbers during analysis and had no information on the identities of suicide victims. All analyses were performed on Health Insurance Review Agency computer systems.

Results

The general characteristics of suicide case subjects are summarized in

Table 1. A high proportion were in the age range of 36–64 years or were of low socioeconomic status. Of the 4,341 persons who committed suicide, 2,063 (47.5%) had at least one underlying disease in the categories of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, or psychiatric illness.

Table 2 lists the differences in 24-hour mean concentrations of 10-μm and 2.5-μm particulate matter between case and control periods according to different time lags. For all time lags except lag 3, concentrations of particulate matter were higher during case periods compared with control periods. The mean difference in particulate matter exposure between the case and corresponding control periods was higher for lag 1 and cumulative lag 1 compared with other time lags.

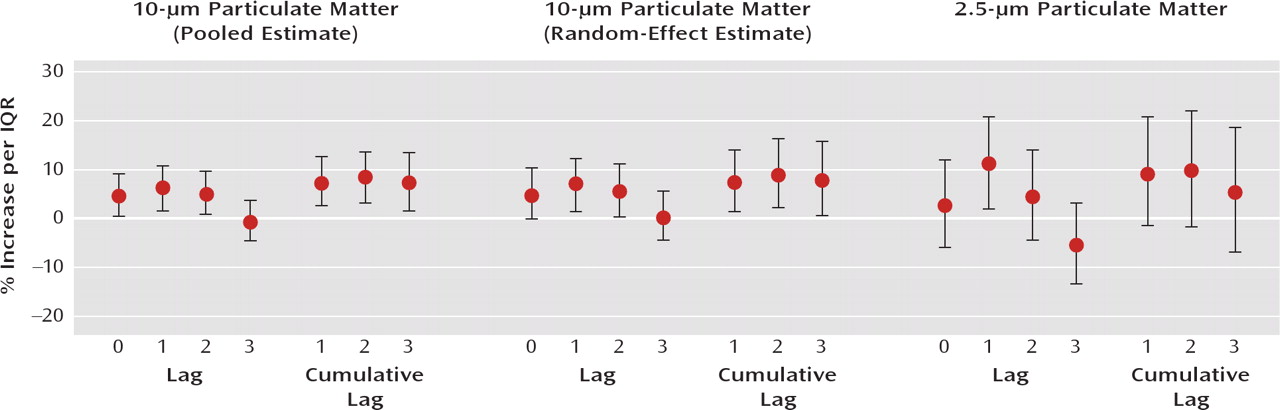

Figure 1 shows the estimated increase in suicide risk associated with an interquartile range increase in particulate matter for different time lags. In the random-effects estimate, 10-μm particulate matter was significantly associated with an increased suicide risk for all time lags except lag 3; lag 0 showed borderline significance (p=0.06). The pooled effect estimate produced similar results. In contrast, 2.5-μm particulate matter was not significantly associated with suicide risk, with the exception of lag 1.

After stratification of suicide cases by underlying disease, a statistically significant association between 10-μm particulate matter and suicide risk was observed among individuals with cardiovascular disease, but not among those who did not have cardiovascular disease (

Table 3). In contrast, the effect of 10-μm particulate matter on suicide risk for the other disease strata was statistically significant in individuals without the underlying disease but not in those with the disease; however, these effects were not statistically significant after excluding individuals with cardiovascular disease. The effect of 2.5-μm particulate matter on suicide risk was not statistically significant in individuals with or without the underlying diseases. There were no statistically significant effect modifications in the association between particulate matter and the risk of suicide by underlying diseases (e.g., the difference between groups with and without cardiovascular disease) for either 10-μm particulate matter or 2.5-μm particulate matter.

Figure 2 presents the cumulative lag 2 effect estimates for suicide stratified by age, sex, season of death, and socioeconomic status. In both pooled and random-effects estimates, 10-μm particulate matter was significantly associated with increased suicide risk in males, in those in the age range of 36–64 years, during seasonal transition periods, and in those of middle socioeconomic status (quintile 2, p=0.06 in random-effects estimate). Similarly, 2.5-μm particulate matter was associated with an increased suicide risk in those in the age range of 36–64 years, during seasonal transition periods, and in those of middle socioeconomic status (quintile 3). However, there were no statistically significant effect modifications in the association between particulate matter and the risk of suicide by any of the stratified variables for either 10-μm particulate matter or 2.5-μm particulate matter.

Discussion

Numerous studies have reported the adverse health effects of air pollution; however, most have focused on physical illness, and only a few have examined the effect of air pollution on mental health (

4,

17). To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has examined the effects of particulate matter on suicide. In this study, we assumed that the effects of ambient particulate matter on suicide were similar to those of physical illness, in which symptom exacerbation occurs in the acute phase (

10). Therefore, we assessed the effect of ambient particulate matter during the day of suicide and the 3 days prior to suicide.

We observed that transient increases in particulate matter concentration were associated with increased suicide risk. For individuals with cardiovascular disease, an interquartile range increase in 10-μm particulate matter was associated with an 18.9% increase in suicide risk. After excluding days above the 95th percentile of 10-μm particulate matter exposure to minimize the influence of outliers, 10-μm particulate matter concentration was associated with a 17.2% (95% CI=5.3–30.3) increase in suicide among all cases and a 51.1% (95% CI=2.3–123.3) increase in the cardiovascular disease group, according to the random-effects model.

Although a significant association between ambient particulate matter and suicide was observed in this study, we can only speculate on the reasons for it. The observed association might be due to neurotoxic substances of ambient particulate matter components, such as lead, mercury, diesel exhaust particles, and manganese (

18,

19), which can directly affect neurobehavioral functions (

20,

21). Because we used the case-crossover study design to assess short-term rather than long-term exposure to particulate matter, and the concentration of each neurotoxic component in ambient particulate matter is usually very low, the neurotoxic effects seem unlikely to contribute much to the association. However, recent studies have suggested the potential neurotoxicity of air pollution in susceptible populations (

22,

23). Research is needed to investigate the neurotoxic effects of ambient particulate matter components at low levels of exposure as well as over the longer term.

Increased particulate matter can affect mental health by contributing to the worsening of physical health and aggravation of chronic diseases. High concentrations of particulate matter can trigger various diseases, and epidemiologic study has demonstrated that the presence or worsening of chronic illness increases the risk of suicide (

24). In the present study, we observed a significant association between particulate matter and suicide for cardiovascular disease only. However, given that individuals with a potentially fatal illness such as cancer have only a small elevation in suicide risk compared with the general population (

25), insufficient statistical power may be the reason our study failed to detect an increased suicide risk with other underlying diseases.

Several studies have suggested that inflammatory mechanisms can be involved in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment and depression (

26,

27), cause endothelial damage to the cerebral vasculature, and contribute to the development of vascular depression (

28). Although depression has been known to be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, which is usually explained by the effects of depression on sickness behavior, including adherence to treatment, there is evidence suggesting that depression or depressive symptoms can be caused independently by inflammation (

29). Particulate matter is a strong inflammatory agent and also contributes to the neuroinflammatory process (

23,

30); thus, it is possible that high levels of inflammation from particulate matter exposure or an underlying disease, such as cardiovascular disease, may aggravate depression or depressive symptoms, thereby increasing suicide risk.

Cardiovascular disease is frequently accompanied by psychiatric illness, although the causal relationships are not fully understood (

31,

32). In this study, one-third of suicide case subjects with underlying cardiovascular disease had been diagnosed with psychiatric illness. Considering that previous studies have found that more than 90% of suicide victims had a psychiatric illness (

33,

34), psychiatric illness might be underdiagnosed in our sample.

We found that increased ambient particulate matter was associated with a higher suicide risk specifically in males, in persons 36–64 years of age, and in those of middle socioeconomic status. It is possible that these groups experienced greater exposure to ambient particulate matter. Alternatively, insufficient statistical power may be responsible for the failure of our study to detect elevated suicide risk in other strata. Seasonal transition periods (spring and fall) were also associated with a higher suicide risk, suggesting that exposure to particulate matter might be higher during these periods (

15,

35). However, because individual exposure to particulate matter and factors associated with individual susceptibility were not evaluated in this study, further studies are needed to better understand this issue.

Recent epidemiologic and experimental studies have consistently demonstrated that exposure to 2.5-μm particulate matter affects physical health more severely than does 10-μm particulate matter. In this study, among case subjects in Seoul, the effect estimate of 2.5-μm particulate matter (10.1%; 95% CI=2.0–19.0) was larger than that of 10-μm particulate matter (6.4%; 95% CI=0.8–12.1%) in lag 1, even though the interquartile range of 10-μm particulate matter was wider than that of 2.5-μm particulate matter. The effect estimates of 2.5-μm particulate matter in cumulative lag 1 (8.0%; 95% CI=–0.9 to 17.8) and cumulative lag 2 (9.3%; 95% CI=–0.9 to 20.5) were greater than those of 10-μm particulate matter in cumulative lag 1 (6.4%; 95% CI=0.1–13.2) and cumulative lag 2 (7.5%; 95% CI=0.4–15.1); however, the effect of 2.5-μm particulate matter was not statistically significant. It is possible that in addition to having too small a sample of suicide cases to reveal the association between particulate matter and suicide, the effect of 2.5-μm particulate matter might be more acute than that of 10-μm particulate matter, and thus the cumulative-lag model was not appropriate to investigate the association between 2.5-μm particulate matter and suicide. However, we could not fully explain these findings, and further research is necessary.

This study had some important limitations. First, misclassification bias may have occurred because we used the death certificate database to identify suicide cases. However, to improve the accuracy of the death statistics database, the National Statistical Office of the Republic of Korea reviews all reported death certificates and conducts interviews with relatives if additional information is needed. According to a recent study comparing hospital records to the death statistics database, the overall accuracy regarding cause of death was 91.9%, although the accuracy for suicide cases in particular was not available (

36). Because postmortem examination data from the National Police Agency was used to identify suicide cases, misclassification bias may not have affected our study results. Second, as in most epidemiologic studies of particulate matter, both city-specific particulate matter concentration and place of residence were used to estimate particulate matter exposure of suicide cases; thus, the particulate matter data used in the analysis may differ from actual exposure levels. Finally, in determining the association between particulate matter and suicide, there may be confounding variables that we did not consider.