Asthma in children and adolescents has increased in prevalence over the past two decades and has become a major public health issue in industrialized countries (

1–4). In 2006, 5.6 million school-age children were reported to have asthma in the United States. On average, in a classroom of 30 children, three are likely to have asthma. Some population studies have shown that the mortality risk remains greater in asthmatic adults despite the gradual decline in general mortality in higher-income nations (

5–7). Asthma is the sixth leading cause of death in children 5–14 years of age in the United States (

5), although deaths have been found to be rarer in children than in adults (

8). Further exploration of causes of death is needed to develop effective strategies for prevention of premature mortality in youths with asthma.

The burden of asthma is substantial for young people and includes general physical health consequences, such as repeated attacks (

4), as well as mental health consequences, which have been identified in several studies (

9–11). For instance, a study in the United States (

9) that enrolled more than 1,300 youths 11–17 years of age with and without asthma found that 16.3% of those with asthma met DSM-IV criteria for one or more anxiety or depressive disorders, compared with 8.6% of those without asthma. Some epidemiological research has shown an association between asthma and suicidal ideation in young people (

12); this association appeared to be independent of the presence of depression and other mental disorders. However, information is lacking from prospective studies about suicide mortality as an outcome and the distribution of causes of death in this population.

Studies have monitored asthma mortality in young people, finding a decrease in rates over recent years (

3,

13), and some studies have investigated risk factors for asthma mortality from deceased cases (

1,

3). However, whether asthmatic youths are more likely to die from causes other than asthma remains unclear, in part because of the very large cohorts required. In this study, we linked data from a population-based asthma survey of more than 160,000 children with 12-year mortality statistics and investigated the association between presence and severity of asthma and suicide mortality.

Method

Participants

The asthma survey used in this study had recruited students 11 to 16 years old in grades 7 to 9 from 123 junior high schools in the Kaohsiung and Pingtung areas in southern Taiwan (N=170,457) from October 1995 to June 1996, as previously described (

2). Permission to visit the schools was obtained from the Taiwan Bureau of Education. Participants and their parents completed a video questionnaire and a written questionnaire. Of 165,173 sets of questionnaires that were completed, 2,407 sets were excluded because of an invalid national identity number, so that 162,766 participants were included in this analysis.

The instruments used for measuring respiratory and allergic illnesses and related variables in this study have been described previously (

2) and are summarized below. The original purpose of the survey was to investigate the association between indoor and outdoor air pollution and asthma. All participants received a complete description of the original study and provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Committee on Human Subjects of Kaohsiung Medical University.

Written Questionnaire

The written questionnaire elicited information on respiratory and allergic illness and symptoms. Sections of the questionnaire answered by parents included questions about the parents' highest education level, cigarette smoking and any alcohol consumption by the student (present or absent for each), family smoking (whether at least one family member living with the student was a regular smoker), and the student's exercise habits (none, seldom, usual). Parents were also asked to answer questions about their children's history of runny nose and sneezing apart from infection; conjunctivitis symptoms; atopic dermatitis; and allergic rhinitis. The asthma status and symptom profile of each student were obtained through the video questionnaire.

Video Questionnaire

The video questionnaire (

14), developed by the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, consisted of five sequences of young people displaying signs of asthma. The scenes depicted were 1) moderate wheezing at rest, 2) wheezing and shortness of breath after exercise, 3) nocturnal waking with wheezing or whistling, 4) nocturnal waking with cough, and 5) severe wheezing and shortness of breath at rest. After each sequence, students were asked whether their breathing had ever been like that of the person in the video, and if so, whether it had been in the past 12 months. Each question was presented in written form on the screen and also printed on a one-page answer sheet that was completed during the screening of the video. The term “asthma” was not mentioned during the video until all five sequences had been completed. Students completed the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Questionnaire after watching the video. Students with a positive response to any of questions 1 to 5 in the past year were defined as having current asthma (N=20,383). Students who had any positive response in their lifetime but not during the past year were defined as having previous asthma (N=9,749). The remainder were defined as having no asthma (N=132,634).

Linkage With the National Mortality Database

Each citizen of Taiwan has a unique national identity number, which was used as an identifier in the linking process to search for deceased participants, as described previously (

15). The sample for this analysis was electronically linked with databases from the Department of Health Death Certification System in Taiwan issued from January 1, 1995, through December 31, 2007. The linkage process was approved by the Department of Health in Taiwan, and after it was completed, the national identity number of each participant was fully encrypted to preserve anonymity. The cause of death in each mortality case was identified from the Death Certification System, as was the method of each completed suicide.

By December 31, 2007, 161,861 participants were living and 905 had died. The cause of death was listed as suicide for 106 participants. The total duration of follow-up in this study was 1,956,456 person-years.

Statistical Analysis

The baseline characteristics of participants with current, previous, and no asthma were compared using chi-square tests and analysis of variance. Mortality rates for different causes of death were calculated as the incident cases divided by the contributed person-years for each of the three groups. Differences in incidence of specific causes of death between the three groups were investigated using Gehan's generalized Wilcoxon test (

16) and life table survival analysis. Cox proportional hazards analyses were then carried out to compute hazard ratios for the association between asthma and suicide mortality, adjusting for the following covariates: gender, age, cigarette smoking of family members, allergic rhinitis, and tobacco use. The covariates had at least a moderate association with suicide (p<0.15) in the unadjusted regression analyses. A p value of 0.05 was considered significant in the regression analyses. Empirical studies (

17,

18) have indicated a strong correlation between major depression and suicide in adolescence. In order to control for this unmeasured potential confounding factor, we conducted a sensitivity analysis of how depression at baseline might influence our estimates of the association between asthma and suicide; we followed an established methodology (

19) and used modeling according to known associations between asthma and depression and between depression and suicide. Further details are provided in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article. To estimate the potential impact of asthma on suicide, we calculated the population attributable fraction (

20) using the following formula: prevalence of asthma in the population × [(hazard ratio–1)/hazard ratio], where the hazard ratio of asthma on suicide risk is estimated on the basis of the final regression model.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes participant characteristics by asthma status. Those with current or previous asthma were more likely to be male than those without asthma (54.9% compared with 48.6%, χ

2=386.1, df=1, p<0.001). The mean ages at baseline for the three groups were 13.68 years (SD=0.88), 13.71 years (SD=0.90), and 13.77 years (SD=0.88), respectively (F=121.7, df=2, 162681, p<0.001). Proportions of reported cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, allergic rhinitis, and parental education levels of college or beyond were higher in the two asthma groups than in the no asthma group.

Distribution and Incidence of Mortality

Total mortality was only marginally different (p=0.063) among the three groups (

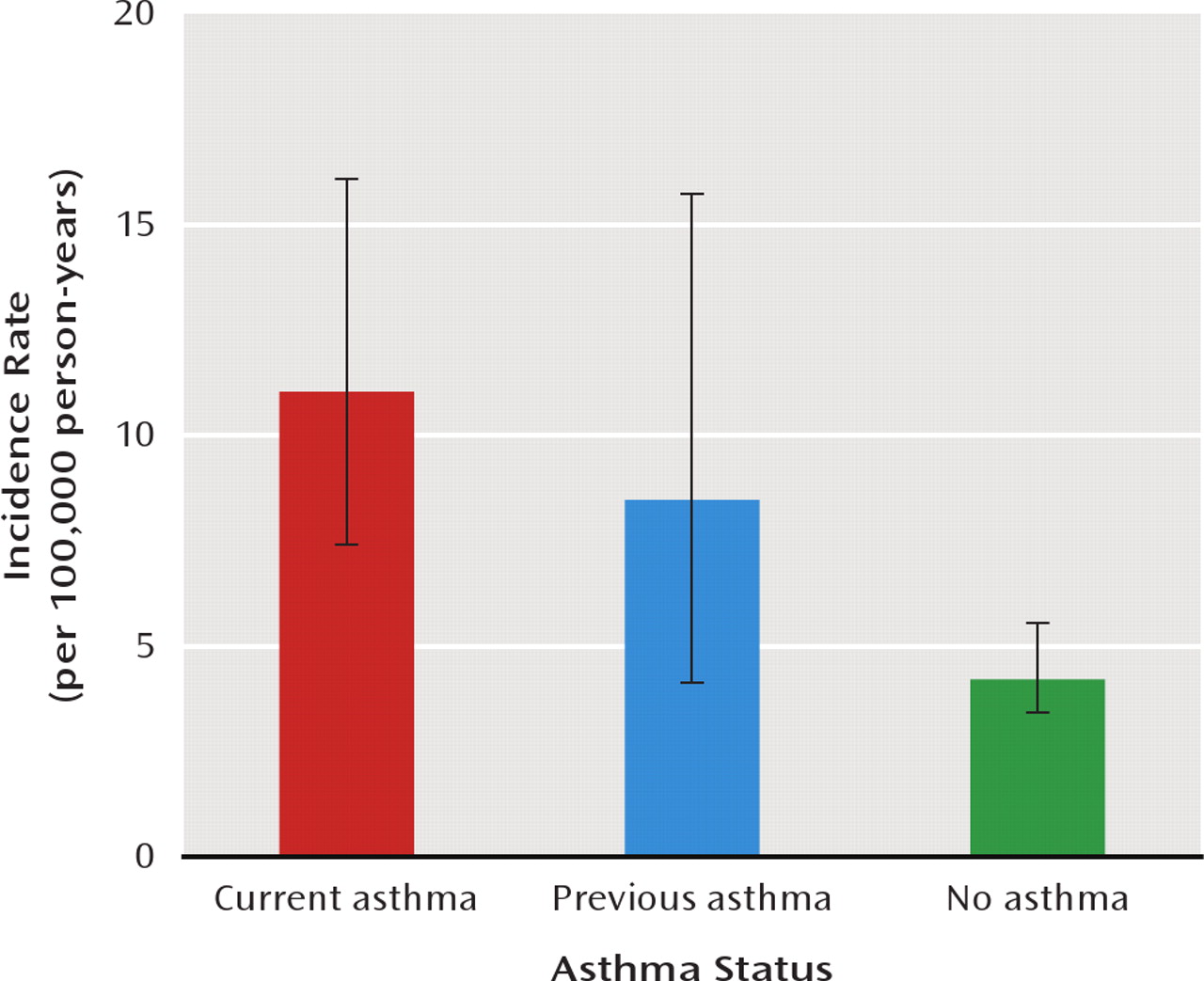

Table 2). Post hoc pairwise comparison revealed that the current asthma group had a higher incidence of mortality than those without asthma (54.7 versus 44.5 per 100,000 person-years, p=0.031). A significant between-group difference was observed in rate of unnatural death (p=0.014) but not of natural death. Among causes of unnatural death, only the incidence of suicide was significantly different between groups (p<0.001). Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between those with current asthma and those with no asthma (p<0.001) and between those with previous asthma and those with no asthma (p=0.045) but not between those with current asthma and those with previous asthma. A total of 106 participants completed suicide during the study period.

Figure 1 summarizes the incidence rates of suicide in those with current asthma, previous asthma, and no asthma. Lower and upper limits of 95% confidence intervals (per 100,000 person-years) were estimated based on the Poisson distribution: 7.3 and 16 for the current asthma group, 4.1 and 15.7 for the previous asthma group, and 3.4 and 5.5 for the no asthma group.

Those who completed suicide (N=106) used various methods, including charcoal burning and other gas poisoning (N=44), jumping from a high place (N=27), hanging (N=23), drugs or poison (N=8), drowning (N=3), and other (N=1); none used firearms, which are not readily available to the public in Taiwan. There was no significant difference in suicide methods used among the three groups.

Association Between Asthma and Risk of Suicide Mortality

Results of unadjusted analyses (

Table 3) showed a significantly higher risk of suicide mortality in the current asthma group compared with the no asthma group (hazard ratio=2.55, p<0.001) and in the previous asthma group compared with the no asthma group (hazard ratio=1.97, p<0.05). Of the potential covariates, male gender, cigarette smoking, and allergic rhinitis were also associated with an elevated likelihood of suicide mortality. Adjustment for gender and age resulted in little change in the observed association between current versus no asthma and mortality (adjusted hazard ratio=2.52, p<0.001) but a more substantial change in the association between previous versus no asthma and mortality (adjusted hazard ratio=1.91, p=0.055). After additional adjustment for cigarette smoking, cigarette smoking by at least one family member, and allergic rhinitis, the current asthma group still had a significantly greater likelihood of subsequent suicide mortality (hazard ratio=2.26, 95% CI=1.43–3.43), and the previous asthma group maintained a strong but not statistically significant association between asthma and suicide mortality (hazard ratio=1.76, p=0.097). There was no multiplicative interaction between asthma and cigarette smoking in the association between asthma and suicide. Our sensitivity analysis to control for the unmeasured potential confounding effect of depression showed no substantial difference in the association between asthma and suicide mortality (see the online data supplement).

Association Between Symptoms and Risk of Suicide Mortality

Results of unadjusted analyses indicate that four of the five symptoms reported from the video questionnaire (night wheezing was the exception) were associated with increased suicide risk (

Table 4). After adjustment for covariates, three of the symptoms remained significantly associated with an elevated suicide risk: exercise wheezing (hazard ratio=2.16, p<0.01), night cough (hazard ratio=2.37, p<0.05), and severe wheezing (hazard ratio=2.66, p<0.01). The hazard ratios for students who had one or two symptoms and more than three symptoms, compared with those without any symptoms, were 1.93 (95% CI=1.16–3.21) and 2.84 (95% CI=1.35–5.97), respectively.

Population Attributable Fraction

Based on the Cox proportional hazards analysis, the attributable risk of suicide accounted for by asthma in the current asthma group was estimated as 0.558 (1.26/2.26). Based on the youth population, the percentage of the population attributable fraction was 7.0% ([20,383/16,2766] × 0.558).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first large community-based cohort study to investigate the association between asthma and suicide mortality in young people. The study utilized a national identification system that allowed effective tracking of mortality except for rare instances of people who migrated outside of the country during the study period.

Although an association between asthma and suicidal ideation or attempts has been found in some studies of general adult populations (

21–23) and of younger people (

12,

24), nearly all of these studies were limited by use of cross-sectional data, with the exception of one follow-up study of adults (

25). Therefore, definitive inferences cannot be drawn about the direction of effect or the sequence of onset of disorders, which are critical to the development of intervention strategies.

Possible Explanation for the Lack of Association Between Asthma and Natural Deaths

One surprising finding of this study was the lack of association between asthma and natural deaths—that is, deaths coded as physical illness-related. Previous studies (

1,

8,

13) have concluded that childhood death due to asthma is a potentially preventable event. Since 1995, the national health insurance system in Taiwan has covered nearly all citizens, providing children and adolescents with an easily accessible health care delivery system with potentially greater success in controlling recurrent asthma attacks. It is possible that this system provides a contextual effect to lower the risk of mortality due to asthma and other natural causes in young people. The significantly higher suicide mortality rate may reflect an inherently underrecognized issue of suicidality in this specific population and signal a need to consider other preventive measures.

Recent Asthma Versus Previous Asthma

The results of this study have several important implications. First, a substantial portion of children with asthma had remission of symptoms at some time after diagnosis (

26), as a result of either the natural course of the disease or early commencement of therapy (such as inhaled corticosteroids) to prevent the progression of the disease. In this study, after adjustment, the current asthma group had approximately twice the risk of suicide mortality compared to those who reported never having had asthma, while those with previous but not current asthma did not have a significantly raised risk. One study (

9) found that young people with a more recent asthma diagnosis had the greatest risk of psychiatric comorbidity. Participants with current asthma were likely to have had more chronic and persistent asthma symptoms for a longer period. Therefore, the higher prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity could contribute to the risk of subsequent suicide. Unfortunately, our data set did not contain information on reasons for remission of symptoms within 1 year of baseline in the previous asthma group. If symptoms had remitted because of medication treatment (such as with steroids), the type and amount of medications might play a role in the association of interest. These issues warrant further investigation. Additionally, the adjusted hazard ratio for the previous asthma group was still sizable (1.76) in the final model despite not reaching statistical significance (p=0.097).

Severity of Asthma and Suicide Mortality

The second important finding of this study was that higher levels of baseline asthma symptoms were also associated with higher suicide mortality. A similarly strong association between cumulative number of medical illnesses and the estimated risk of suicide has been reported in older adult populations (

27). Previous studies (

28,

29) have also found that greater asthma symptom severity is positively associated with anxiety and depressive disorders. Suicide in asthma may result from a complex relationship between physical, psychological, and social burdens. Young people with more asthma symptoms will have a higher perceived physical burden, possibly intermingled with psychiatric comorbidity and greater impairment of their daily functioning. A third finding was that severe wheezing at rest, which was the most severe among the five symptoms, was associated with a higher risk of suicide than other symptoms. Taken together, these findings suggest that a dose-response relationship exists between the severity of symptoms and suicide, providing some support for an underlying causal relationship.

Small Confounding Effects of Depression and Smoking

In the sensitivity analysis (see the online data supplement), depression at baseline had a small potential confounding effect on the association between asthma and suicide. This is consistent with previous studies finding that depression does not explain the association between asthma and suicidal ideation or suicide attempt (

12,

25). However, depression might play a role as a mediating factor resulting in suicide mortality, an issue that we were not able to evaluate in this study because of the single baseline assessment. It is conceivable that individuals who developed depression after baseline were more likely to interpret respiratory symptoms as a serious medical disorder, especially when symptoms were persistent and severe. The low prevalence of tobacco use in young people in this study is likely due to the strict control policy for tobacco use in Taiwanese high schools. However, our findings are consistent with a previous study (

24) showing that adolescents with asthma were more likely than those without asthma to use tobacco. The prevalence of asthma is commonly reported to be higher among children of low socioeconomic status (

30,

31), although some studies have found the reverse or no association at all (

32,

33). It is necessary to consider whether socioeconomic status confounds the association between asthma and suicide. The only component of socioeconomic status available in our study was parental educational level, which was not associated with suicide mortality in the unadjusted regression analysis.

Limitations

The limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the measures of asthma were limited to self-report, and we had no data on lung function (e.g., spirometry) or information from medical records. From a clinical perspective, an asthma diagnosis is based on a clinician's judgment derived from the history of symptoms, signs on examination, and impaired respiratory function on investigation (

34). However, in international epidemiological research, the most common method for defining asthma and its severity is through self-report in the context of a structured questionnaire. In this study, the video facilitation (

35) we used for eliciting a symptom profile has been validated and found to reduce sources of bias from language, culture, literacy, or interviewing techniques and therefore is particularly useful when comparing asthma prevalence and severity in different populations.

Second, in this study, as in all studies of suicide mortality, other causes of death (usually “accidental”) may have been substituted in official registers to avoid any potential stigma associated with suicide (

36). Our data, however, revealed no significant differences in the rates of accidental death among the three groups, which reduces the likelihood of biased certification as an explanation for the observed findings.

Third, the analysis in this study linked mortality with survey data collected on a single occasion and did not consider postbaseline information, in particular changes in exposure status. Given that the dates of suicide death were widely distributed across the follow-up period, individual patterns of the clinical course of asthma may play an important role, although assessment of this question would have required regular clinical follow-up. Such a study design may be difficult to implement because of the low incidence of suicide and the large sample required. Further insight might be gained through case-control studies that obtain information by psychological autopsy. Potential unmeasured confounders or mediators include anxiety disorders and childhood adversity. Anxiety is implicated as a risk factor for suicide in people with mental disorders (

37) and is also related to asthma (

9). Additionally, some data (

10) suggest that exposure to childhood abuse and neglect might account for both asthma and mental disorders. Further research is needed to clarify the role of childhood adversity as a predisposing factor to suicide in asthmatic young people.

Implications

We found that young people with asthma in Taiwan have an elevated risk of suicide mortality, with about 1 in 14 suicides in this population potentially attributable to asthma. Suicide is a relatively rare but tragic outcome, and associations with asthma might well reflect more common levels of mental distress. School staff, clinical staff, and family members should be reminded of the need for awareness of, and prevention measures to improve, mental health in young people, particularly those with more severe and persistent asthma symptoms.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ya-Tang Liao, M.S., for providing statistical advice and Xiao-Wei Sung, B.S., for data analysis. Dr. Stewart is funded by the National Institute for Health Research Specialist Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London.