Some commonly used antipsychotic medications (e.g., olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) are associated with higher rates of metabolic abnormalities that predispose patients to cardiovascular disease (

1–

7). Individuals with severe mental disorders have a substantially shortened life expectancy, and cardiovascular diseases are among the leading causes of premature mortality in this group (

8). Thus, appropriate treatment strategies for patients who take antipsychotics and also have significant risk factors for cardiovascular disease are needed. Among the methods for managing this risk in patients treated with antipsychotic drugs, a commonly chosen option of uncertain effectiveness is switching from drugs with a high liability for producing metabolic side effects to one with a low liability. This is of particular interest for individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who are clinically stable taking an antipsychotic medication that has a relatively high risk of metabolic side effects. The possible benefits of switching to a drug associated with fewer adverse metabolic effects must be weighed against the potential risk of clinical instability associated with changing treatment.

There are numerous modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and impaired glucose metabolism (including insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus). Recent attention has focused on non-high-density lipoprotein (non-HDL) cholesterol, which contains all known and potentially atherogenic lipid particles and has been shown in large cohort studies to be strongly associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

For example, the Lipid Research Clinics Program Follow-Up Study, which followed a cohort of 2,462 middle-aged men and women for an average of 19 years, found that non-HDL cholesterol levels at study entry strongly predicted cardiovascular disease mortality (

9). Differences of 30 mg/dl in non-HDL cholesterol at baseline were associated with a 19% increase in cardiovascular disease mortality in men and an 11% increase in women. In the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI), in which 1,514 patients with multivessel coronary artery disease were followed for 5 years, non-HDL cholesterol was strongly and independently associated with nonfatal myocardial infarction and angina pectoris; increments of 10 mg/dl in non-HDL cholesterol were associated with a 5% increased risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction and a 10% increased risk of angina pectoris (

10).

In this article, we report the primary and key secondary efficacy and safety results of a 24-week randomized controlled clinical trial. The study examined the effectiveness of switching treatment for patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder from olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone to treatment with aripiprazole as a strategy to reduce metabolic problems associated with antipsychotic medications. We considered studying the switch to other antipsychotics with favorable metabolic profiles, including ziprasidone and molindone (

3,

6,

11–

13), but chose aripiprazole because it was the newest option and we expected it would be of most clinical interest when the study was completed.

We hypothesized that switching to aripiprazole would result in an improvement in metabolic measures compared to staying on the current antipsychotic medication. We also wanted to determine if any metabolic benefits of switching to aripiprazole would be accompanied by clinical destabilization after switching from an antipsychotic that was working well. The primary efficacy outcome was the difference in non-HDL cholesterol from baseline between the two treatment groups. The key secondary outcome was efficacy failure, defined in the protocol as psychiatric hospitalization, a 25% increase in the total Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS;

14) score, or ratings of much worse or very much worse on the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) change subscale (

15).

Method

Participants

The Comparison of Antipsychotics for Metabolic Problems (CAMP) was a multisite, parallel-group, randomized controlled clinical trial. Participants were individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who had achieved clinical stability with olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone and who were at increased risk for cardiovascular disease as indicated by a body mass index (BMI) ≥27 and a non-HDL cholesterol ≥130 mg/dl (if non-HDL cholesterol was 130–139 mg/dL, then low-density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol was required to be ≥100 mg/dl). The patients were required to be on the qualifying drug for a minimum of 3 months without dosage adjustments and without any other antipsychotic for 1 month prior to enrollment. The patients entered the study in order to improve their metabolic risk profile. All participants provided written informed consent after the study procedures had been fully explained. The study was conducted at 27 clinical research centers affiliated with the Schizophrenia Trials Network in the United States.

The patients were randomly assigned on a 1:1 basis to either switch to aripiprazole or stay on their current antipsychotic medication. Treatment assignments (stay versus switch) were stratified by the antipsychotic medication taken when entering the study (olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone) and were centrally implemented via a web-based system accessed by the clinical centers. Individuals assigned to stay on their current antipsychotic remained on their prestudy dosage with adjustments only as clinically indicated. The allowed dosages were as follows: olanzapine, 5–20 mg/day; quetiapine, 200–1,200 mg/day; and risperidone, 1–16 mg/day. Patients assigned to switch to aripiprazole began taking aripiprazole, 5 mg/day, and continued their previous antipsychotic medication and dose for 1 week. After 1 week, the aripiprazole dosage was increased to 10 mg/day and the previous drug's dosage was reduced 25%–50%. After 2 weeks, the aripiprazole dosage could be increased to 15 mg/day while the previous drug's dosage was reduced 50%–75% from the original dosage. After 3 weeks, the available range for aripiprazole was 5–20 mg/day and the previous drug was stopped. After 4 weeks, the allowed dosage range for aripiprazole was 5–30 mg/day.

All participants received a manualized behavioral intervention, adapted from a group treatment (

16,

17), that was aimed at improving exercise and diet habits to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. Patients returned to the clinic for weekly visits during the first month of the treatment period and every 4 weeks after that, and laboratory assessments were conducted every 4 weeks. The behavioral intervention was provided in person at all postbaseline study visits. After the first 4 weeks, study personnel made a telephone call to reinforce the behavioral treatment lessons between each of the monthly visits.

The raters of symptoms (PANSS), global clinical status (CGI), and extrapyramidal side effects (the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale [

18], the Barnes Akathisia Scale [

19], and the Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Symptoms Scale [

20]) were blinded to treatment assignment. Participants and their physicians were aware of their medication assignments.

The addition of lithium, valproate, lipid-lowering agents such as statins, or drugs prescribed for weight loss was not allowed during the trial because of possible effects on the primary study outcome. Individuals taking stable doses of lithium, valproate, or lipid-lowering medications at the time of study entry could continue these treatments, but dose adjustments during the treatment period were not allowed. All other medications, except for nonstudy antipsychotics, were allowed.

Statistical Methods

The primary efficacy analysis was conducted on the efficacy-evaluable population, defined as all patients randomly assigned to a study group who received at least one dose of study medication and completed at least one postbaseline efficacy assessment. The efficacy analysis corresponded to a comparison of change in non-HDL cholesterol from baseline to 24 weeks between treatment groups (stay versus switch). Repeated measurements mixed effects linear models were fit for the primary analysis and secondary analyses of continuous outcomes that appropriately accounted for the correlation among repeated clinical assessments and randomly missing data (

21). Models included fixed effects for stratification (incoming medication), pooled clinical site, baseline value, treatment, time (weeks in study), and time by treatment interactions. An unstructured variance-covariance matrix was assumed, and least squares means at 24 weeks were the a priori basis for the treatment comparisons. Outcome measurements obtained following a prohibited change in dose or initiation of a disallowed medication were excluded from all efficacy analyses, as specified a priori in the study protocol. The primary efficacy analysis was repeated using all available measurements to assess the sensitivity of results.

Secondary analyses of efficacy failure and treatment discontinuation were based on the intent-to-treat population, defined as all patients randomly assigned to a study group who received at least one dose of study medication. We used Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests stratified by incoming medication to compare treatment groups with respect to the proportion experiencing efficacy failure and the proportion discontinuing treatment. Kaplan-Meier curves for time to efficacy failure and time to treatment discontinuation were generated, and treatment groups were compared using log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazards models were additionally fit to compare time to event outcomes, controlling for incoming medication and pooled clinical site.

Results

The study was conducted between January 2007 and March 2010.

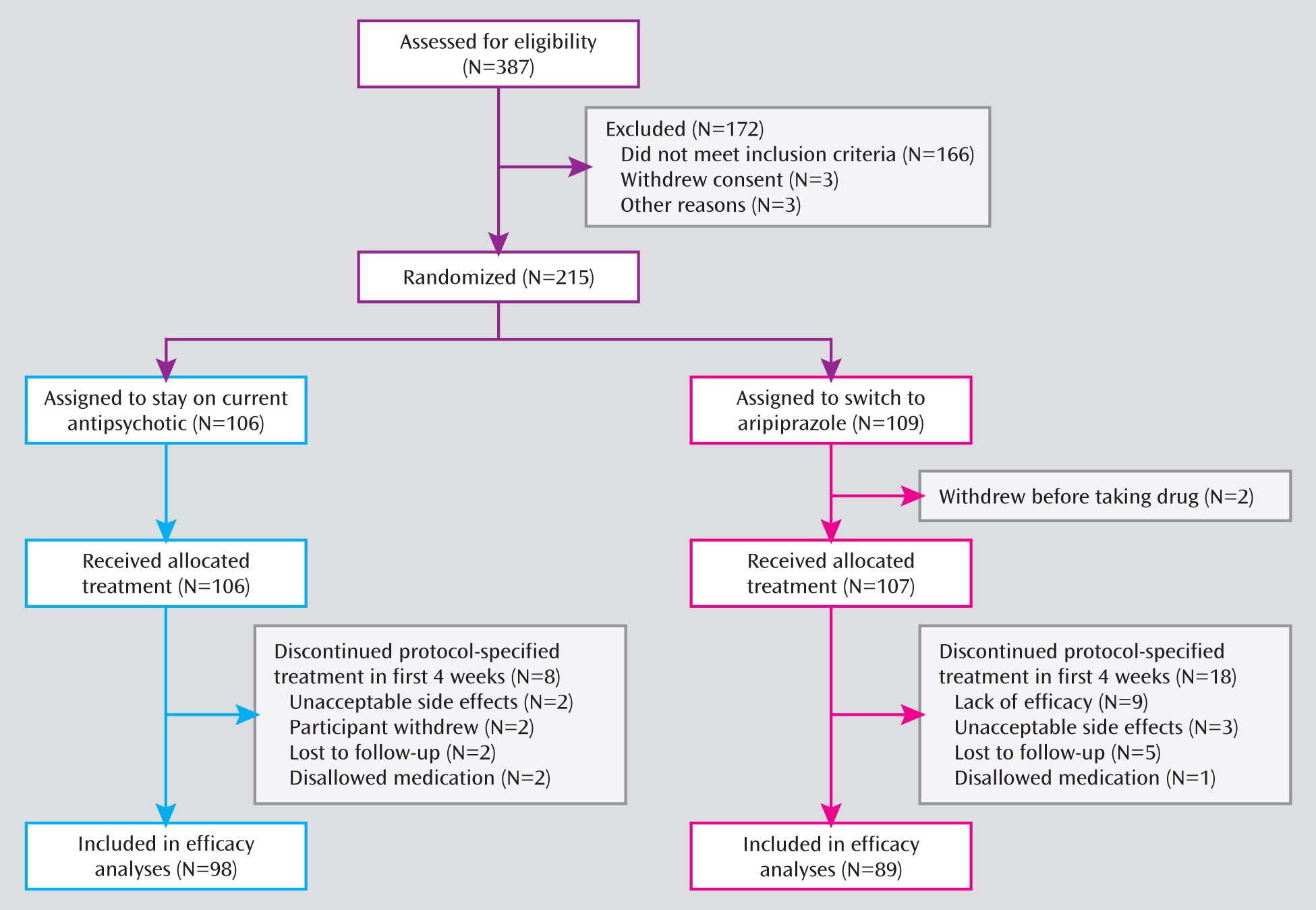

Figure 1 summarizes the progress of patients who were screened and randomly assigned to each group. Of the 215 patients who met inclusion criteria, 109 were switched to aripiprazole and 106 remained on their current antipsychotic. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of all participants are summarized in

Table 1.

Two patients who were assigned to switch medications never took the study drug and were therefore not included in the intent-to-treat population. Eighteen of those in the switch group (16.8%) compared with eight in the stay group (7.5%) stopped the protocol-specified treatment in the first 4 weeks before completing the time allowed for cross-titration to aripiprazole and before the first follow-up laboratory tests were conducted, and they were therefore excluded from the efficacy-evaluable population. Of these, 17 of those who switched (15.9%) and six of those who stayed (5.6%) discontinued the assigned antipsychotic, and the remaining three (one switcher and two stayers) took disallowed medications in the first month. The primary outcome and other metabolic parameters were evaluated in 89 switchers and 98 stayers who completed at least 1 month of study participation and thus had at least one postbaseline measurement of the primary outcome on the assigned treatment.

At study entry, the mean daily doses of the qualifying medications were 18.5 mg of olanzapine, 502 mg of quetiapine, and 4.1 mg of risperidone. Mean daily doses for patients during the study were 16.9 mg of aripiprazole, 18.0 mg of olanzapine, 572.0 mg of quetiapine, and 4.1 mg of risperidone.

Metabolic Outcomes

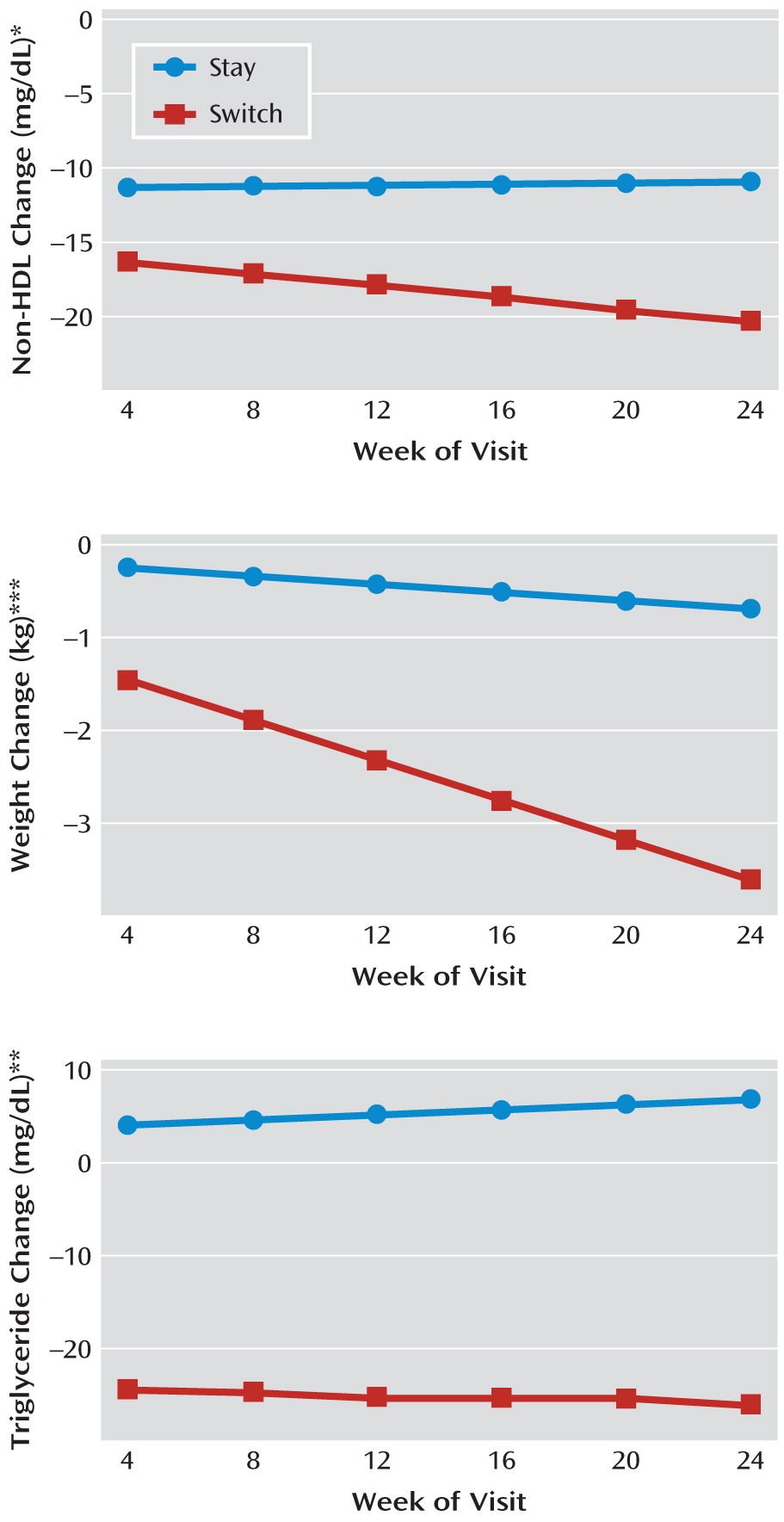

For the primary outcome (change in non-HDL cholesterol) the least squares means decreased more for the switch than the stay groups (–20.2 mg/dl compared with –10.8 mg/dl), with a difference of –9.4 mg/dl (95% confidence interval [95% CI]=–2.2 to –16.5, p=0.010). Switchers lost more weight than stayers (–3.6 kg compared with –0.7 kg) with a difference of –2.9 kg (95% CI=–1.6 to –4.2, p<0.001) and had a larger BMI reduction of –1.07 units (p<0.001). Triglycerides decreased for the switch group and increased for the stay group (–25.7 mg/dl compared with +7.0 mg/dl), yielding a difference of –32.7 mg/dl (95% CI=–12.1 to –53.4, p=0.002). As seen in

Table 2, there were no significant differences between the treatment groups in changes in HDL or LDL cholesterol. There was a trend favoring switching compared with staying in reducing the inflammatory marker C-reactive protein.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 demonstrate the time course of changes in non-HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and weight. The benefit of switching for non-HDL cholesterol and triglycerides was almost completely realized after only 1 month, while the advantage of switching for weight change accrued over the 24 weeks of the study. In our models, time and time-by-treatment parameters were significant for weight change but not for non-HDL cholesterol or triglycerides. Mean weight change per month on study treatment was –0.8 kg (SD=1.4 kg) for switchers and –0.1 kg (SD=1.0 kg) for stayers.

On measures of glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity, there was no difference between switchers and stayers in fasting glucose, fasting insulin, or glycosolated hemoglobin. There was no difference in glucose levels 2 hours after oral ingestion of 75 mg of glucose, but the 2-hour insulin level decreased more for those assigned to switch compared with those assigned to stay (–31.1 mg/dl and –6.8 mg/dl, respectively), with a difference of –24.2 mg/dl (p=0.014).

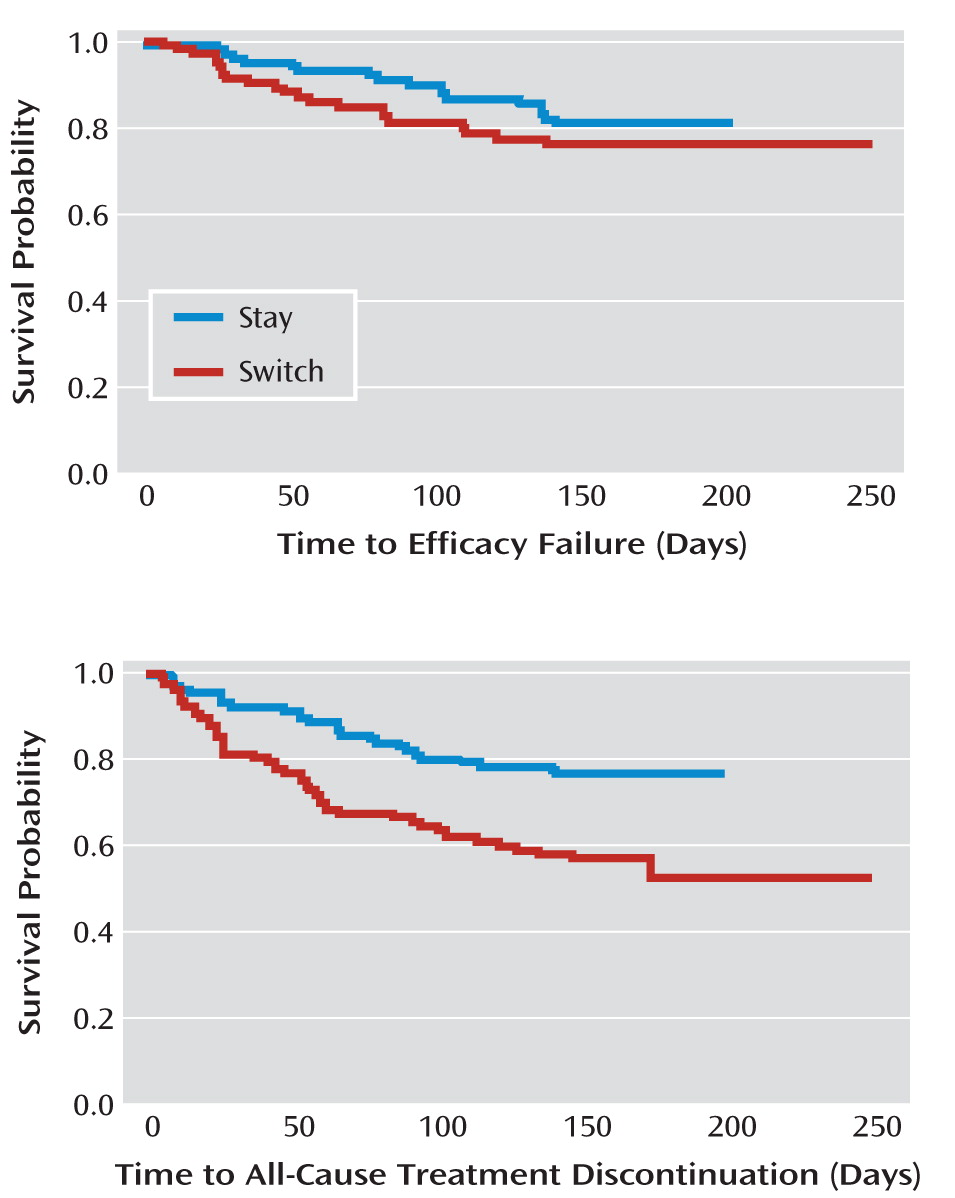

Measures of Clinical Status

Twenty-two patients assigned to switch to aripiprazole (20.6%) and 18 assigned to stay on the current antipsychotic (17.0%) experienced efficacy failure. There was no significant difference in time to efficacy failure (hazard ratio for switching=0.747; 95% CI=0.395–1.413, p=0.3703). There were no differences between groups in psychopathology changes as measured by the PANSS total score, change in CGI severity score, or change in the Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (

22) mental health scores. The 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey physical health score worsened slightly for the stayers and improved for the switchers, yielding an advantage for the switchers of 3.7 points (p=0.0105). On the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life–Lite Questionnaire, a validated measure of quality of life related to weight (

23), switchers improved more than stayers (–14.2 compared with –4.7 points, p=0.0028).

Treatment Discontinuation

Eighteen of those assigned to switch to aripiprazole (16.8%) discontinued the protocol-specified treatment before 1 month had elapsed compared with eight of those assigned to stay on the current medication (7.5%). Overall, 51 switchers (47.7%) and 29 stayers (27.4%) stopped the protocol-specified treatment (by stopping the assigned antipsychotic or beginning a prohibited medication) before 24 weeks were complete (p=0.0019). Participants in the switch group discontinued the protocol-specified treatment (for any cause) earlier than those in the stay group (hazard ratio=0.456; 95% CI=0.285–0.728, p=0.0010). Forty-seven switchers (43.9%) and 26 stayers (24.5%) stopped taking the assigned antipsychotic altogether before 24 weeks were complete.

Adverse Effects

We systematically inquired about 20 adverse events commonly associated with antipsychotic medications.

Table 3 lists the frequencies for participant ratings of each of these side effects as moderate or severe. Considering the adverse effects reported after baseline with differences of approximately 5% or more between the stay and switch groups, insomnia was more common in the switch group but there was more sleepiness, hypersomnia, nausea, dry mouth, increased appetite, and akinesia among the stay group. Among the switchers, 18 patients (16.8%) experienced a total of 21 serious adverse events (including medically significant or life-threatening events, hospitalizations, or extended hospitalizations), compared to 10 stayers (9.4%) who experienced 14 serious adverse events. One stayer and no switchers discontinued treatment due to akathisia/activation. Eight switchers (7.5%) and five stayers (4.7%) were hospitalized for psychiatric reasons. There were no deaths in the study.

Sensitivity Analysis

A sensitivity analysis of the primary efficacy outcome (change in non-HDL cholesterol) was conducted using a modified intent-to-treat population of participants with at least one postbaseline non-HDL measurement. A repeated measurements mixed effects linear model was fit using all available measurements of non-HDL cholesterol, regardless of disallowed medication usage or early discontinuation of the prescribed antipsychotic, to predict the change at week 24. The change remained greater among patients switching to aripiprazole than those remaining on their original medication, but statistical significance was not achieved. The difference in least squares means was 5.8 mg/dl (p=0.104).

Discussion

The study was conducted at 27 U.S. research sites that were selected to include a demographically diverse population to enhance the generalizability of the results. Enrollment criteria were designed to include a wide spectrum of individuals who might consider switching medications because of metabolic problems, although those with minimal metabolic problems and those with severe metabolic problems that needed immediate intervention were excluded. Therefore, the results of this study might best be generalized to individuals with chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder with moderate metabolic problems for whom a medication change or a lifestyle intervention focused on diet and exercise is the appropriate first step.

In this study, switching from olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone to aripiprazole was effective in helping many patients improve the results of their lipid profiles (lower non-HDL cholesterol and triglycerides levels) and lose weight. The 9 mg/dl reduction in non-HDL cholesterol is slightly less than the 10 mg/dl difference that significantly reduced cardiovascular morbidity in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation study (

10). The 1.1 unit reduction in BMI is above the 1 unit considered clinically significant by a panel of antipsychotic experts who created monitoring guidelines (

24). Because weight loss continued at the end of the study, it is possible that our results underestimate the long-term benefit of switching on this secondary outcome. Because non-HDL cholesterol was the primary predesignated outcome, results pertaining to non-HDL cholesterol provide stronger evidence than those for secondary outcomes. These results are consistent with those in a randomized controlled trial reported by Newcomer and colleagues (

25) that examined switching from olanzapine to aripiprazole over 16 weeks. In that study, switchers had a 3.21 kg advantage in weight loss after 16 weeks, a reduction in triglycerides (compared with an increase for the stayers), and a 15.6 mg/dl larger reduction in non-HDL cholesterol.

Aripiprazole is one of several antipsychotics, including ziprasidone and molindone, associated with a relatively low risk of metabolic problems. In studies, switching to ziprasidone has been associated with significant improvement in metabolic parameters (

12,

13). In addition, other available strategies to address metabolic problems in patients taking antipsychotic medications include statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) to reduce LDL cholesterol and metformin to reduce weight. Statins tend to benefit LDL and triglycerides rather than HDL or weight. The different statins have variable effects on LDL cholesterol, but they are typically associated with reductions in LDL cholesterol of 30%–60% (

26). Short-term studies of metformin have shown that it is effective and well tolerated in promoting weight loss among individuals who have recently gained weight while taking an antipsychotic (

27), individuals experiencing a first episode of psychosis (

28), and even individuals whose increased weight is not of recent onset (

29).

Switching antipsychotics by beginning aripiprazole at a low dose and titrating upward while slowly discontinuing the previous antipsychotic over 1 month was not associated with a significant increase in efficacy failures as indicated by need for hospitalization, substantial worsening of symptoms, or global clinical status. However, a larger percentage of individuals assigned to switch to aripiprazole discontinued the assigned treatment over the 24 weeks of the study. In some cases, the medication discontinuation was attributed to inadequate efficacy by the study clinician but did not meet the study criteria for efficacy failure. The protocol was designed to minimize risks for participants and allowed study physicians to intervene to prevent problems before they became severe. For example, when clinical worsening was detected, study physicians could intervene by discontinuing the protocol-specified treatment, thus averting full-blown efficacy failure. We investigated this possibility by comparing the PANSS scores of participants who met the protocol's efficacy failure criteria to the PANSS scores of participants whose treatment discontinuations were judged to be a result of inadequate efficacy but who did not meet the efficacy failure criteria; the PANSS scores of those who met efficacy failure criteria were higher (mean=71.7 [SD=22.9]) than those who did not meet the criteria (mean=59.5 [SD=15.2]). This suggests that careful clinical monitoring following a medication switch, accompanied by appropriate clinical intervention when poor efficacy is detected (e.g., stopping the new antipsychotic and restarting the previous one), can reduce the risk of severe symptom exacerbations and the need for hospitalization.

Because the goal of the study was to evaluate the effect of switching antipsychotic medications on metabolic parameters, some common medication changes that were known to affect these parameters were not allowed. For those few patients who took the proscribed medications but continued the assigned antipsychotic, we used only those measurements taken before the disallowed change occurred in the primary analyses. Seven such deviations from protocol-specified treatment occurred; four were in the switch group and three in the stay group. In addition, some patients contributed data after they had stopped taking the assigned antipsychotic. Results from the sensitivity analyses that were conducted to assess the impact of these exclusions and early dropouts for other reasons showed that an advantage for switching remained, although statistical significance was not achieved.

Our study focused on the primary comparison of staying on current medication or switching. Secondary analyses examining the effects for each of the three allowed antipsychotics at study entry are provided in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article. These secondary analyses provide only suggestive information about the impact of switching from these drugs.

Open-label treatment is a limitation of this study, particularly for outcomes not measured in the laboratory but instead subject to clinical judgment. For example, a belief that olanzapine has superior efficacy could have contributed to the early discontinuations among those who entered the study taking olanzapine but were assigned to switch to aripiprazole (supplemental Table 3). The excess of early treatment discontinuations in the olanzapine group suggests that switching from olanzapine was either more difficult than switching from the other drugs or, perhaps, resulted from an expectation bias that this change would be the most difficult.

In conclusion, switching from a medication associated with substantial risk of metabolic problems to one with a lower risk of these complications is a reasonable clinical option if careful cross-titration and close monitoring is possible. Careful clinical monitoring during and after a switch is necessary, and the diligence of clinicians is likely a principal reason that those who switched did not experience a higher rate of efficacy failures than those who stayed on their original antipsychotic. If switching medications is unsuccessful, other approaches to reduce some of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease are available, including adding metformin or a statin. The switch in medications was effective in the presence of a behavioral intervention that was focused on improving diet and exercise habits, which also benefitted the group that did not change medications.