In recent years, the methodological quality of randomized controlled trials of a variety of treatments has been more closely examined, particularly in meta-analyses and systematic reviews (

1). In assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials of psychotherapy, special considerations are necessary because of the unique nature of psychotherapy as an experimental condition. Unlike medication, in psychotherapy the treatment and treatment delivery are highly interwoven, taking shape in a complicated human interaction unfolding over time. Issues such as training and supervision of psychotherapists, replicability of the treatment protocol, and verification of psychotherapist adherence and competence are all important to the validity of a psychotherapy trial. For these reasons, a subcommittee of APA's Committee on Research on Psychiatric Treatments developed a rating scale for the quality of randomized controlled trials of psychotherapy, the Randomized Controlled Trial of Psychotherapy Quality Rating Scale (RCT-PQRS) (

2).

CBT, from its inception, grew out of basic and applied research (

4,

5), and it remains closely tied to ongoing research. Psychodynamic therapy, in contrast, grew out of a clinical tradition, and critics argue that psychoanalysis went on to develop a culture that eschewed the use of science (

6). Whereas Gerber et al. (

3) found 94 randomized controlled trials of psychodynamic therapy in the literature, there are far greater numbers of randomized controlled trials of CBT. Thus, we predicted that the quality of CBT trials would be significantly higher than that of psychodynamic therapy trials.

We predicted that lower quality would be related to larger effect sizes, reasoning that a looser internal validity could provide more room for a variety of experimenter biases to influence outcome in ways that would yield more significant results. We also predicted that lower quality would be related to greater variability of outcomes as a result of the general effects of less tightly controlled experimental conditions.

Discussion

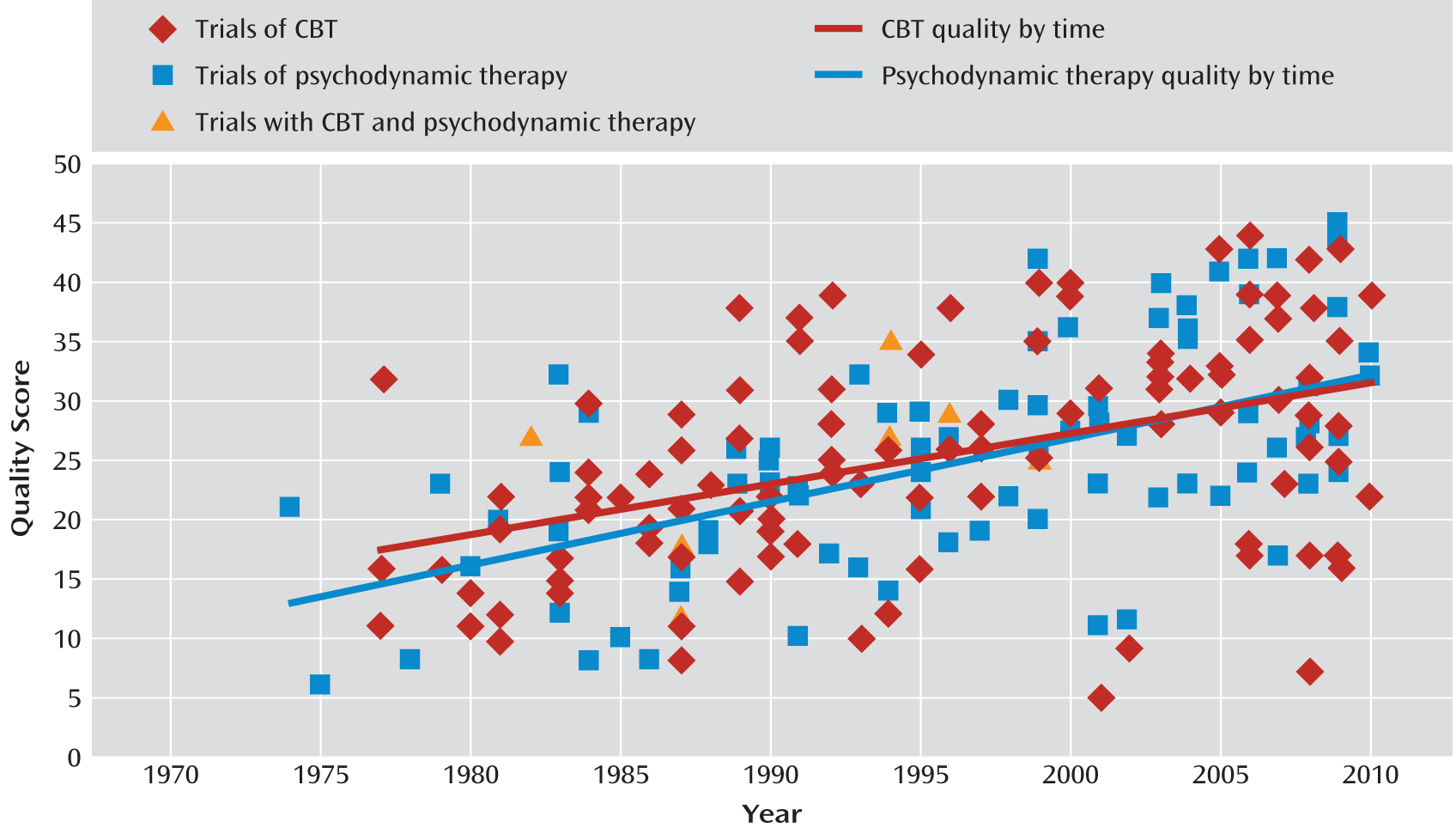

Perhaps the most surprising finding of this review was the lack of a significant difference between the mean quality scores of 113 randomized controlled trials of CBT for depression and 87 randomized controlled trials of psychodynamic therapy for a variety of diagnoses. Our hypothesis that CBT trials would be of higher quality because of the historically stronger emphasis on research within the culture of CBT than within that of psychodynamic therapy was not supported. This finding calls attention to the existence of high- and low-quality studies within both CBT and psychodynamic therapy trials. In

Figure 2, the regression lines for CBT and psychodynamic therapy trial quality scores by year of publication appear to be nearly coincident. Statistical tests indicated that the strength of the correlation between quality score and year of publication was not significantly different; neither were the slopes or intercepts of the regression lines. Both sets of studies have been improving over time, and both contain randomized controlled trials with a similar range of quality.

While the psychodynamic therapy trials covered a range of diagnoses and the CBT trials centered on depression, we see no theoretical reason why diagnosis should be related to methodological quality. Furthermore, no difference was observed between the CBT trials and the subset of 13 psychodynamic therapy trials that focused on depression. Hence, we believe that the comparison of quality between the two samples of studies is a fair one.

It should be borne in mind that only the methodological quality of the trials of CBT and psychodynamic therapy was compared in this study. The question of comparing outcomes of the two treatments has been systematically addressed elsewhere (

23,

31–

33). Moreover, the lack of a significant difference in mean quality score between the two modalities does not indicate that the evidence base for the treatments is equivalent or even similar. The number of CBT trials far outstrips that of psychodynamic therapy trials (

34), adding robustness to the overall support for CBT. An assessment of the evidence base using the specific criteria of empirically supported treatments (

35) indicates “strong support” for 17 CBT treatments for a variety of DSM-IV-TR diagnoses, whereas only one psychodynamic therapy treatment—Kernberg's transference-focused psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder (

36)—currently meets this level of support (

37). This difference is largely due to a lack of replication with the same treatment manual by different research teams in randomized controlled trials of psychodynamic therapy (

3).

The trials of CBT for depression appear to have specific areas of strength and weakness. Areas of strength appear to be in diagnostic methods for inclusion or exclusion, description of treatments, use of validated outcome measures, a priori specification of primary outcome measures, justification of comparison groups, use of same time frame for comparison groups, and appropriate randomization between groups. Areas of weakness include description of comorbidities, blinding of outcome assessment, discussion of safety and adverse events, use of intent-to-treat method, and statistical consideration of therapist and site effects. The latter three areas were also found to be deficient in the psychodynamic therapy trials (

3), indicating that these are areas in particular need of attention in the design and implementation of future psychotherapy trials. Item 13, reporting of safety and adverse events, received the lowest total score of any item when individual items were summed across studies, indicating a gross lack of reporting in this area. Attention has been called to the potential for adverse effects of psychotherapy (

38), and we hope that future randomized controlled trial research will bring greater transparency to this issue.

When examining the relationship between quality and outcome, our prediction of an inverse relationship between quality and effect size was supported, indicating that lower-quality CBT trials were associated with better outcome for CBT. This finding lends empirical support to the hypothesis that the manner of trial implementation may affect the validity of trial results and highlights the importance of maintaining rigorous methodological quality in psychotherapy trials. The items and item anchors of the RCT-PQRS, aimed at assessing trial features across six methodological domains, may help in defining and operationalizing standards in trial implementation. The finding of an inverse relationship between quality and effect size also indicates that the results of some previous meta-analyses may have overestimated the effects of CBT for depression, which is likely also the case for psychotherapies for depression in general (

7). The moderating effect of quality on outcome speaks to the importance of incorporating validated measures of quality into meta-analyses. While we would not necessarily predict that the magnitude of the relationship between quality and outcome in the present study is universal and stable across treatments and diagnoses, the use of an instrument such as the RCT-PQRS would allow for sensitivity analyses to investigate whether such a relationship is present.

In addition to predicting that lower quality would be related to inflated outcome, we also predicted that lower quality would be related to greater variability of outcome as a result of less tightly controlled experimental conditions. This prediction was supported, indicating that low quality might be associated not only with bias but also with greater error and thus lower reliability of results.

Our study had several limitations. Item-level reliability was not high across all items of the RCT-PQRS, and thus item-level descriptive analyses must be considered exploratory. Furthermore, we did not conduct item-level statistical analyses aimed at uncovering which methodological features were most related to outcome or whether all items were related to outcome in the same direction. However, summation across items was able to capture an aggregation of the influence of low quality in the studies examined.

An additional limitation in this regard is that the observed correlation between quality and outcome could be caused by a third variable, such as publication bias. If trials with null results that go unpublished also happen to be low in quality, the published trials included in our analysis could represent a biased sample of the population of relevant trials and could thus contain an excess of low-quality trials with large, significant effects. The exclusion of missing (unpublished) low-quality trials with null results from the metaregression may have had a greater influence on the observed relationship between quality and outcome than differences in experimental conditions in the included trials. However, making assumptions about the quality of theoretically missing studies is inherently speculative. Furthermore, given the strong correlation observed between standard error (a proxy for sample size) and quality score, the effects of quality versus publication bias on outcome are difficult to disentangle, both conceptually and statistically. In short, we cannot say whether the observed quality-related bias in this study was caused by experimenter bias, other threats to internal validity, publication bias, or some combination of these. Although our study is observational, which limits precise causal inference, we interpret our results as evidence to support the importance of maintaining high methodological quality in randomized controlled trials, particularly in light of the additional observed relationship between low quality and greater variability of outcome.

Another limitation lies in the fact that while ratings with the RCT-PQRS are meant to assess the quality of the trials themselves, ratings are necessarily limited to the information included in the published reports. This is a limitation shared with quality rating scales in general (

39). Nonetheless, it further limits our ability to discern which specific methodological features may be most related to outcome, leading us to use the aggregation of the quality of reporting of specific features as an approximate measure of the overall trial quality. Finally, the raters in our study were not blind to any details of the studies. While there was good interrater reliability among raters of varying orientations, and while the RCT-PQRS attempts to anchor individual item levels with enough specificity to minimize judgment and bias in item ratings (

2), we must acknowledge the possibility that some ratings were affected by halo effects related to factors such as prestige level of journals or reputation of study authors. The effects, as well as feasibility, of blinding studies in the context of quality ratings may be an area for future research (

15,

40).