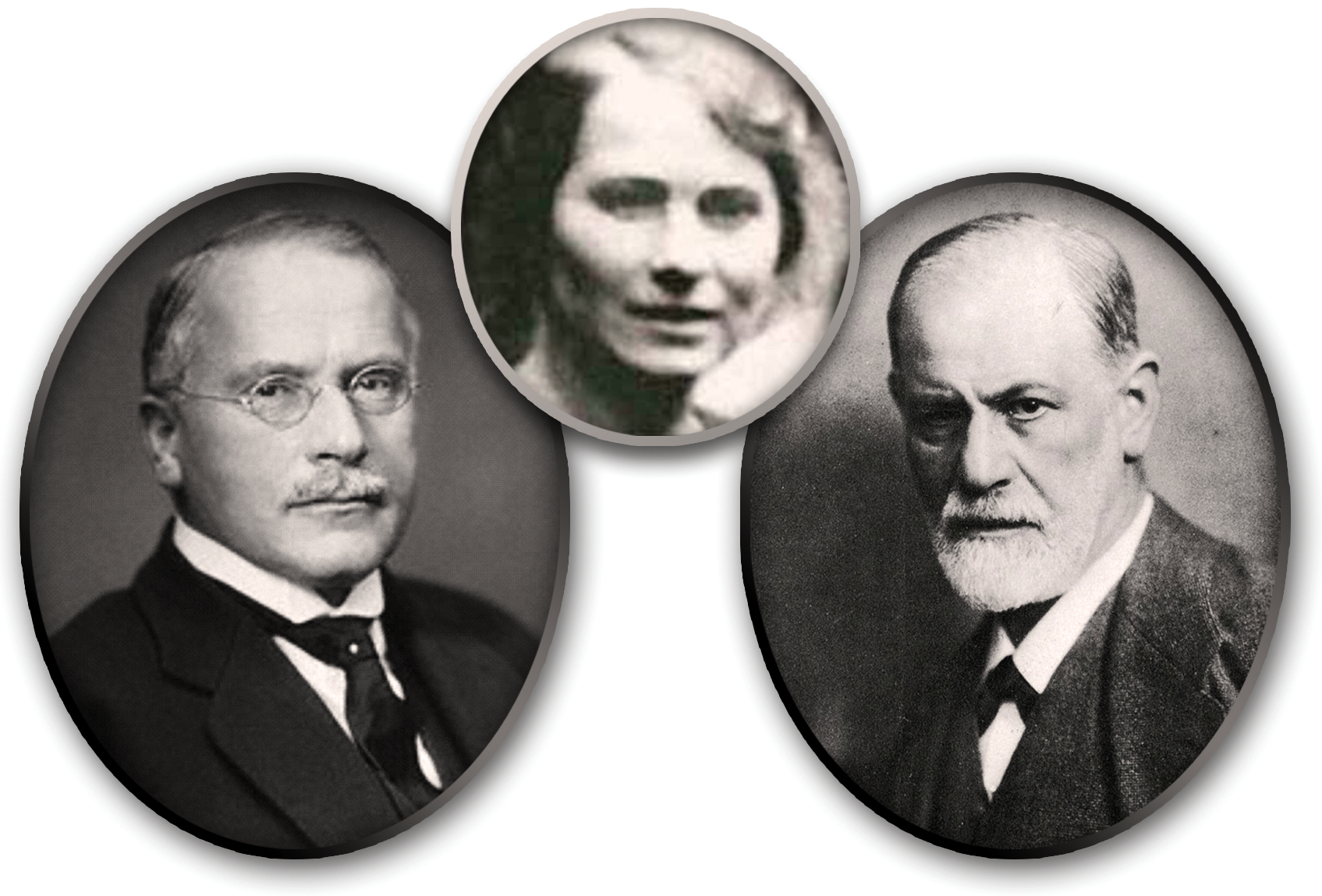

In November 1885 Sabina Spielrein was born in Rostov-on-Don, Russia, into the family of a businessman (Nikolai) and his dentist wife (Eva). She was a brilliant student, but in 1904, soon after she finished high school, she was dropped off by her uncle and a medical police officer at the Burghölzli Psychiatric Clinic in Zurich, headed by Eugen Bleuler (

1). Her hospital records noted, “The patient laughs and cries in a strangely mixed, compulsive manner, … masses of tics, rotating head, sticks out her tongue, legs, twitching” (

2). The notes were written by a newly qualified Carl Gustav Jung, who diagnosed her as having psychotic hysteria on the basis of her difficult childhood, characterized by a “painful love” with her father. In a late letter to Freud, Jung wrote, “The physical chastisements administered to the patient's posterior by her father from the age of four until seven had unfortunately become associated with the patient's premature and now highly developed sexual awareness” (

2). The therapeutic effect of the psychoanalysis exceeded all Jung's expectations, and they fell in love: “During treatment the patient had the misfortune to fall in love with me” (

2). It is unknown whether Jung had sexual intercourse with his “little girl” (

3) or if it was only a platonic “nonerotic love in the therapeutic relationship” (

4). Whatever the truth, 5 years of increasingly intense relations followed, until 1909 (

1), when Jung retired from Burghölzli (

5). He later claimed that he maintained contact with her only because he “feared a relapse.” Nevertheless, the transference romance was characterized by poison-pen letters, talks, correspondence, visits, accusations and counteraccusations, excuses, and rumors (

2), with a clear breach of the doctor-patient boundary (

4). Additionally, Spielrein entered into correspondence with Freud in 1909 and in so doing aggravated the already complex relationship between Jung and Freud (

2).

After leaving the mental hospital in 1905, Spielrein lived independently in Zurich, studying medicine at the university and graduating in 1911 with a dissertation on schizophrenia. She then married and worked as a psychoanalyst. In 1923 she returned to Russia, teaching at the university in Rostov and founding a psychoanalytic children's clinic. The Wehrmacht murdered her and her two daughters in 1941.

Spielrein not only was Jung's patient and lover but also became his muse. In 1977 Carotenuto (

6) was the first to write about her as a possible inspiration for Jung's concept of the “anima” (

7). She wrote about 30 works (

8), and one of them, “Destruction as the Cause of Being” (1912) is thought to have influenced Freud's later theory of the death instinct (

9).

Elisabeth Marton's documentary

My Name Was Sabina Spielrein (2002) and Roberto Faenza's Italian movie

The Soul Keeper (2002) were the first films about her life, recently followed by David Cronenberg's movie

A Dangerous Method (2011). These movies creatively reenacted Spielrein's hospitalization, using excerpts from her hospital records and Jung's published material on her “case” (

3) and portraying the “love affair” that developed between Jung and Sabina, with the following triangular relationship involving her, Jung, and Freud.