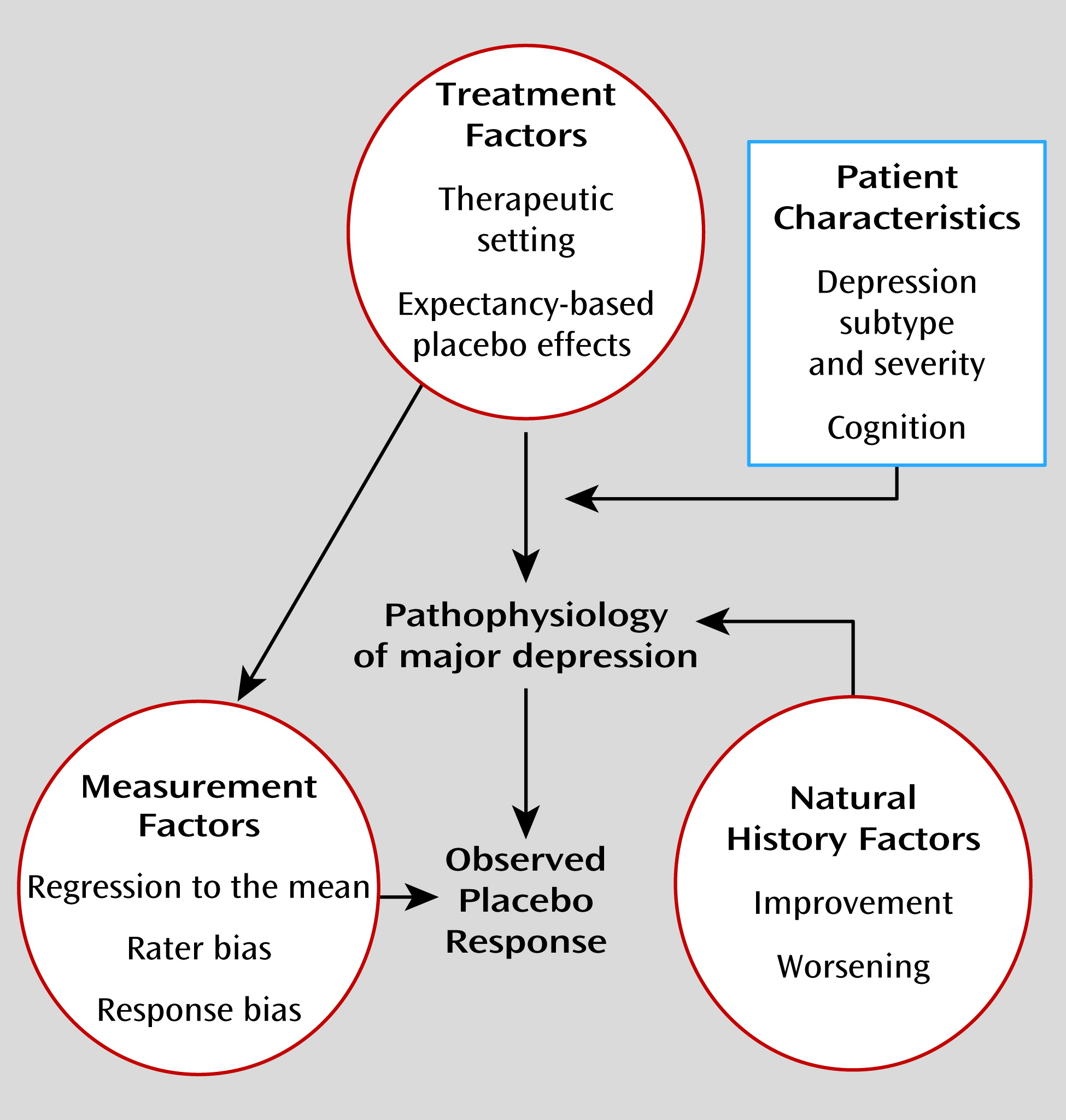

Expectancy

Two theoretical approaches that have been proposed for understanding the mechanisms of placebo effects are expectancy theory and classical conditioning (

12). Expectancy theory postulates that placebo treatments instill a (conscious) positive expectation of improvement in the patient that actually causes the change in a patient’s symptoms. Conditioning theorists hold that the placebo response represents a type of nonconscious learning in which an individual associates improvement in symptoms (unconditioned response) with a neutral stimulus such as pills, health care providers, or procedures (conditioned stimulus) that itself becomes capable of eliciting an effect (conditioned response). In general, both conscious expectancy and nonconscious conditioning mechanisms likely contribute to the placebo effects observed in pharmacologic studies. However, given the importance of verbal information in shaping placebo effects and the fact that substantial placebo effects are observed in treatment-naive patients, most empirical studies of the mechanisms of placebo effects in antidepressant clinical trials have focused on patient expectancy.

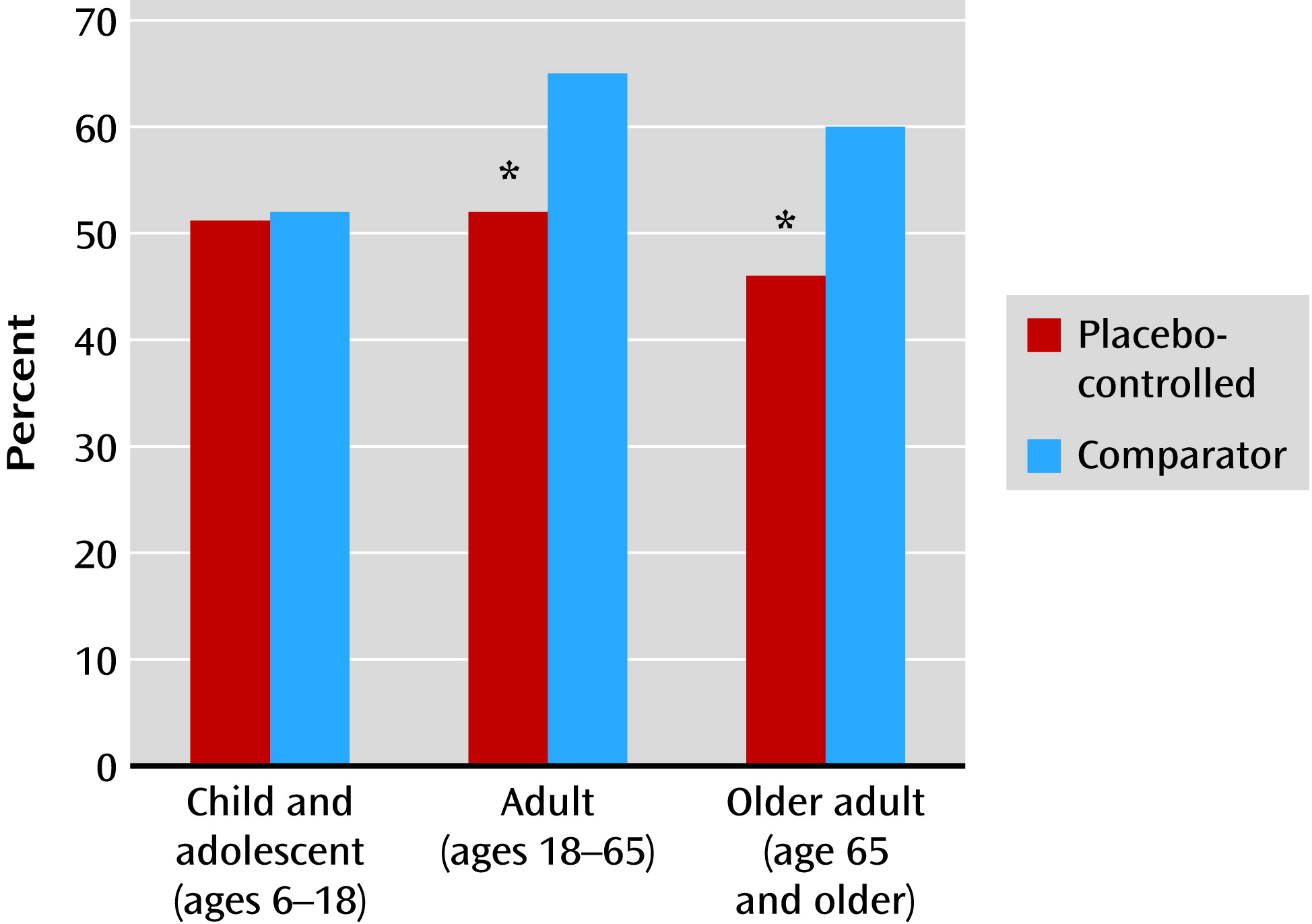

Khan et al. (

13) first reported that the number of treatment arms in a study was negatively correlated with the “success” of the trial, defined as finding a significant difference between drug and placebo. A greater number of treatment arms increases the probability of receiving active medication, which may increase patient expectations and generate higher placebo response rates. The influence of patient expectancy on antidepressant response has also been observed in comparisons of medication response between placebo-controlled trials (i.e., one or more medications compared with placebo) and active comparator trials (i.e., two or more medications with no placebo group) (

Figure 2). In adults and older adults with major depression, mean medication response rates in comparator trials are significantly greater than in placebo-controlled trials (

14,

15). Patients in comparator trials know they have a 100% chance of receiving an active medication, which may increase their expectancy of improvement, leading to enhanced placebo effects and greater observed antidepressant response.

Consistent with these results, Papakostas and Fava (

16) reported that the probability of receiving placebo in a clinical trial was negatively correlated with antidepressant and placebo response. For each 10% decrease in the probability of receiving placebo, the probability of antidepressant response increased 1.8% and the probability of placebo response increased 2.6%. Similarly, Sinyor et al. (

17) evaluated 90 randomized controlled trials of antidepressant medications for unipolar depression, comparing response and remission rates between trials comparing medication to placebo (drug-placebo), two medications to placebo (drug-drug-placebo), and one medication to another (drug-drug). They found that medication response was significantly higher in drug-drug studies (65.4%) compared with drug-drug-placebo studies (57.7%) and drug-placebo studies (51.7%) (p<0.0001). Response to placebo in placebo-controlled trials was significantly higher in drug-drug-placebo studies compared with drug-placebo studies (46.7% and 32.2%, respectively; p=0.002).

These meta-analytic results suggest that the design of a clinical trial shapes patients’ expectancy of symptom improvement during the trial, which in turn influences response to antidepressant medication and placebo. However, the veracity of this interpretation must be tested in studies that directly measure patient expectancy in different types of antidepressant clinical trials and determine the relation of expectancy to treatment outcome. Two studies that measured patient expectancy at baseline found that higher expectancy predicted greater symptom improvement during treatment of depression with antidepressant medication (

18,

19). In a recent pilot study (

20), expectancy was experimentally manipulated by randomizing 43 outpatients with major depression to placebo-controlled (i.e., 50% chance of receiving active drug) or comparator (i.e., 100% chance of receiving active drug) administration of antidepressant medication. Randomization to the comparator condition resulted in significantly greater patient expectancy relative to the placebo-controlled arm of the study (t=2.60, df=27, p=0.015). Among patients receiving medication, higher pretreatment expectancy of improvement was positively correlated with change in depressive symptoms observed over the study, although the relationship fell short of significance (r=0.44, p=0.058). The manipulation of expectancy in that study permits the causal inference to be made that more positive expectancy leads to greater improvement in depressive symptoms, both within a single type of clinical trial and between different trial types.

In summary, the consent procedure for pharmacotherapy trials, in which prospective participants are made aware of the study design, the past effectiveness of the drugs and placebos used in the study, and the investigator’s opinions of the treatment options, influences patients’ expectancies of how participation in a clinical trial will affect their depressive symptoms. Expectancy appears to be a primary mechanism of placebo effects and significantly influences both observed placebo response and antidepressant medication response. In both treatment groups, patients are receiving a pill that they believe may represent a treatment for their condition.

Therapeutic Setting

Since the ability to generate treatment expectancy requires relatively advanced cognitive capacities, it is puzzling to observe high placebo response in children with depression. Compared with adults, participants in pediatric major depression trials are less cognitively equipped to understand the nature of the study in which they are participating, and they actually receive less information at the time of their enrollment (since their parents provide informed consent). To evaluate the significance of expectancy effects in younger patients, our group analyzed antidepressant response between comparator and placebo-controlled studies of antidepressants for children and adolescents with depressive disorders (

21). Unlike the large differences observed between these study types in adults and older adults with depression, there was no significant difference in medication response between comparator and placebo-controlled studies enrolling children and adolescents.

Rather than patient expectancy, what appeared to influence treatment response was the amount of therapeutic contact patients received: adolescents experienced greater placebo response as the number of study visits increased. In an antidepressant clinical trial, patients experiencing social isolation and decreased activity levels as part of their depressive illness enter a behaviorally activating and interpersonally rich new environment. They interact with research coordinators and medical staff, receive lengthy clinical evaluations by highly trained professionals, and are provided with diagnoses and psychoeducation that explain their symptoms. Medical procedures are performed, such as blood tests, ECG, and measurement of vital signs, and clinicians meet with patients weekly to listen to their experiences and facilitate compliance by instilling faith in the effectiveness of treatment.

Considerable empirical evidence supports the therapeutic effectiveness of these interventions. Optimistic or enthusiastic physician attitudes, as compared with neutral or pessimistic attitudes, are associated with greater clinical improvements in medical conditions as diverse as pain, hypertension, and obesity (

22). A therapeutic relationship in which the clinician provides the patient with a clear diagnosis, the patient is given an opportunity for communication, and the clinician and patient agree on the problem has been shown to produce faster recovery (

23). In addition, physical aspects of the treatment, such as the pill dosing regimen, the color of pills, and the technological sophistication of the treatment procedures, can influence treatment response (

24).

Posternak and Zimmerman (

25) investigated the influence of therapeutic contact frequency on antidepressant and placebo response in 41 randomized controlled trials of antidepressants for major depression. These investigators calculated the change in HAM-D score over the first 6 weeks of treatment in patients assigned to antidepressant medication and placebo, comparing studies that had six weekly assessments (weeks 1–6) with those that had five assessments (weeks 1–4 and week 6) or four assessments (weeks 1, 2, 4, and 6). In placebo participants who returned for a week 3 visit, the reduction in HAM-D score between weeks 2 and 4 was 0.86 points greater than in those who did not, and in placebo participants who returned for a week 5 visit, the reduction in HAM-D score between weeks 4 and 6 was 0.67 points greater than in those who did not. A cumulative therapeutic effect of additional visits on placebo response was observed: between weeks 2 and 6, the mean improvement in HAM-D score was 4.24 points in patients who made weekly visits, compared with 3.33 points in those who made one visit less and 2.49 points in those who made two visits less. Thus, the presence of additional visits appeared to explain approximately 50% of the symptom change observed between weeks 2 and 6 among patients receiving placebo. Participants who received active medication also experienced more symptomatic change with increased numbers of visits, but the relative effect of this greater therapeutic contact was approximately 50% less than that observed in the placebo group.

The intensive therapeutic contact found in clinical trials may be contrasted with what patients being treated with antidepressants receive in the community. In community samples of patients receiving antidepressant medication, 73.6% are treated exclusively by their general medical provider as opposed to a psychiatrist (

26). Fewer than 20% of patients have a mental health care visit in the first 4 weeks after starting an antidepressant (

27), and fewer than 5% of adults beginning treatment with an antidepressant have as many as seven physician visits in their first 12 weeks on the medication (

28). Thus, assignment to placebo in an antidepressant clinical trial represents an intensive form of clinical management that has therapeutic effects.