Bipolar disorder is a recurrent mood disorder. Even though the occurrence of manic episodes is the hallmark that distinguishes bipolar disorder from recurrent unipolar depression, it is the depressive episodes and symptoms that dominate the course of the illness (

1). Patients with bipolar disorder experience depressive episodes three times more often than they do manic and hypomanic episodes (

2–

4). Depressive episodes also entail a significant risk of suicide (

5), and lingering depressive symptoms are a major cause of psychosocial disability (

6). There is thus a great need for effective and safe antidepressant treatment for patients with bipolar disorder.

Mood stabilizers (i.e., lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine) and atypical antipsychotics are effective in treating or preventing manic and hypomanic episodes in bipolar disorder, but with the exception of quetiapine, lurasidone, and olanzapine, their efficacy in treating depressive episodes is limited. Antidepressants are therefore commonly prescribed and constitute 50% of all prescribed psychotropic medication in bipolar disorder (

7). But unlike the state of the evidence for unipolar depression (

8), only a handful of adequately powered studies of antidepressants have been conducted in bipolar depression, and the use of antidepressants in bipolar disorder remains controversial. In fact, neither the European Medicines Agency nor the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved any standard antidepressant as monotherapy for bipolar depression.

The main concern with the use of antidepressants to treat bipolar depression is the risk that they will induce a switch from depression to hypomania or mania. Treatment-emergent switch to mania has been associated with worsened long-term outcome (

9), and some studies report an association between antidepressant treatment and increased mood cycling in bipolar patients (

10).

The potential switch-inducing properties of antidepressants have been discussed since the tricyclic antidepressants were introduced in the 1950s, and it was recognized early on that tricyclics could increase the risk of abnormal mood elevation (11, 12). Since then, several studies of the effects of antidepressants on depressive episodes of bipolar disorder have been conducted, and some have found associations between antidepressants and manic or hypomanic switch (

13–

18), while others have not (

19–

21).

Although the empirical data are arguably inconclusive, current treatment guidelines for bipolar depression reflect a relatively broad consensus that antidepressant treatment can induce mania, and they discourage the use of antidepressant monotherapy. Many guidelines recommend instead the use of atypical antipsychotics or mood stabilizers as a first line of treatment for depressive episodes. Guidelines differ with respect to second-line treatments (and regional differences can be observed as well) (

22), although some endorse the use of antidepressants in combination with antimanic agents, particularly if used for limited periods.

Only a handful of studies have explored whether concomitant use of a mood stabilizer is protective against a switch to mania during antidepressant treatment; some of these studies are affected by confounding by indication, some are underpowered, and collectively they present inconsistent results (

14,

23–

26). Indeed, a large meta-analysis concluded that mood stabilizers were not effective in preventing a switch to mania (

27)—although, as the authors of the study discuss, that finding may have been confounded by indication, as patients treated with mood stabilizers tended to have more manic episodes.

Given the need for effective treatment for depressive episodes in bipolar disorder, it is of great clinical importance to clarify whether antidepressants increase the risk of manic episodes when administered together with a mood stabilizer. If mood stabilizers do not protect against treatment-emergent mania, the current high rate of antidepressant prescriptions places bipolar patients at considerable risk for manic episodes and should be reduced. If, however, antidepressants are safe when used in conjunction with mood stabilizers, then they could be used more liberally to treat bipolar depression.

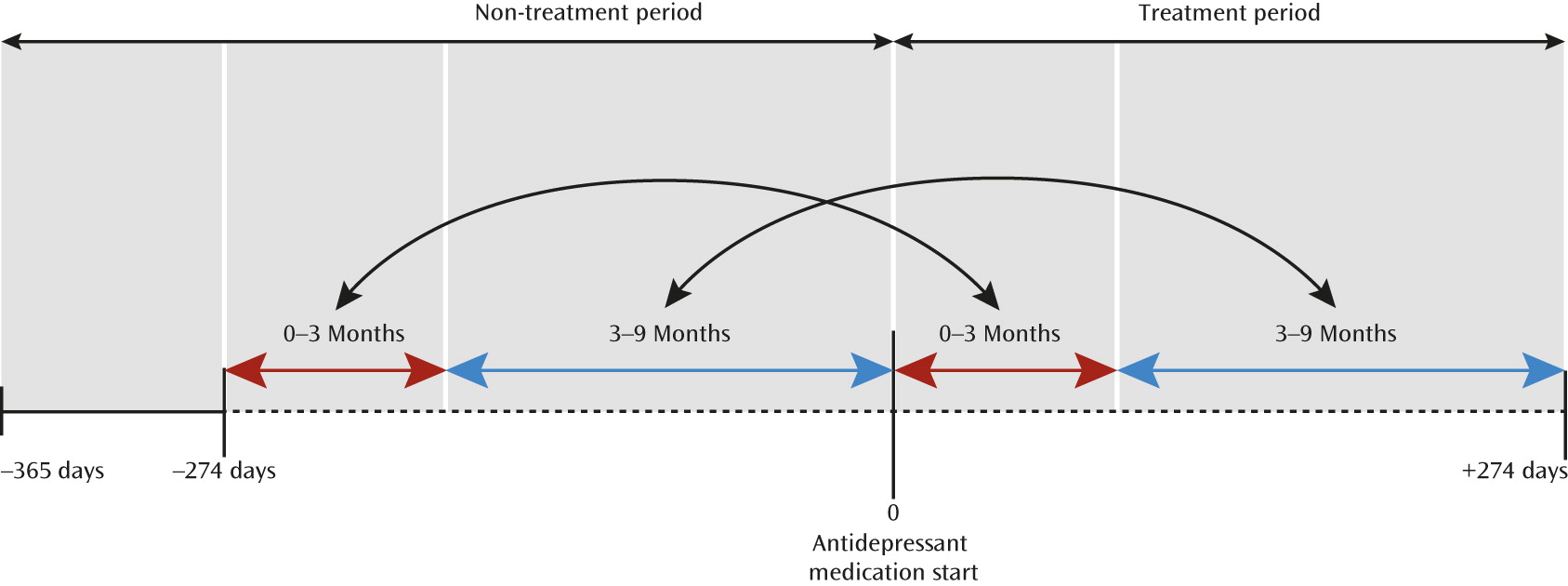

In studies that involve placebo or treatment discontinuation (i.e., clinical trials), there is a risk of sampling bias, as patients with high risk may be unlikely to participate because of disorder severity, as well as for other reasons. Observational studies, on the other hand, sample all patients, including those with high risk, and they yield larger sample sizes. In this study, we used data from national Swedish registries to investigate the effects of antidepressant medication on the rate of mania. We assessed the acute switch effects within 3 months after initiation of antidepressant treatment, as well as longer-term effects up to 9 months after start of medication. We surveyed two groups of patients with bipolar disorder: patients not taking a mood stabilizer who were treated with antidepressant monotherapy, and patients on a mood stabilizer who were additionally treated with an antidepressant. We used a within-individual design to control for potential confounding caused by differences in disorder severity, genetic makeup, and early environmental factors.

Method

Study Subjects

Using the unique individual Swedish national registration number assigned to each individual at birth and to immigrants on arrival, we linked Swedish national registries with high accuracy (

28). Patients with bipolar disorder were identified using the National Patient Register, which includes all Swedish psychiatric inpatient admissions since 1973 and all psychiatric outpatient admissions, excluding those in primary care, since 2001 (

29). The registry contains admission dates along with the main discharge diagnosis ICD code and up to eight secondary diagnosis codes. Patients with bipolar disorder were defined as individuals identified in the National Patient Register who had at least two inpatient or outpatient admissions with a discharge diagnosis of bipolar disorder (ICD-8 codes 296.00, 296.1, 296.3, 296.88, and 296.99; ICD-9 codes 296.0, 296.1, 296.3, 296.4, 296.8, and 296.9; ICD-10 codes F30 and F31) prior to start of treatment with an antidepressant. We excluded patients with any inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-8 code 295, ICD-9 code 295, and ICD-10 code F25) prior to follow-up to reduce the risk of misclassification. An algorithm based on less strict inclusion criteria for bipolar disorder has been demonstrated to yield a high positive predictive value (

30). We identified 31,916 individuals who met these criteria for bipolar disorder.

To ascertain the use of prescribed drugs among these patients, we used the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register (SPDR), which contains data on all dispensed prescribed drugs since July 2005 (

31). Every entry has a prescription and a dispensation date, the name of the medication with dosage and package size, and a medication code in accordance with the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System. Using the SPDR, we identified instances of dispensed prescriptions of antidepressant drugs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants, and bupropion). We also identified patients treated with mood stabilizers (lithium, valproate, and lamotrigine). We included only patients to whom an antidepressant was dispensed with no such dispensations the previous year, thus ensuring that this dispensation was the start of a treatment period. Of the 31,916 patients with bipolar disorder, an antidepressant drug was dispensed to 22,339 patients (70%) between July 1, 2005, and December 31, 2009; of these, 3,240 patients (10.2%) met the criterion of not having received any antidepressant drugs during the previous year.

Exposure

The main exposure was antidepressant use, and we stratified patients by whether or not they received concurrent treatment with a mood stabilizer. To be classified as having a minimally adequate course of treatment with a mood stabilizer, a patient had to have at least two dispensations in the year preceding antidepressant treatment, of which at least one had to occur between 4 and 12 months before the antidepressant treatment began. To be classified as not using a mood stabilizer, a patient could not have any dispensations of mood stabilizers in the year preceding antidepressant treatment. The follow-up in the antidepressant monotherapy group was censored at the time that a mood stabilizer was prescribed, if that occurred.

Outcome

The occurrence of mania was ascertained using discharge diagnosis codes for mania (ICD-10 codes F30.0–F30.2, F30.8–F30.9, and F31.0–F30.2) from the National Patient Register during follow-up from July 2005 through 2009.

Statistical Analysis

The effects of antidepressant medication on the rate of mania were estimated by Cox proportional hazards regression analyses, using the STCOX statement in Stata/IC, version 12.1 (StataCorp., College Station, Tex.). All patients serve as their own control, by conditioning on patient in the analyses, thus reducing confounding by differences between patients in severity of the disorder, genetic makeup, and childhood environment. We compared the individuals during two periods: a 9-month period before antidepressant treatment started and a 9-month period after treatment was started (

Figure 1). To account for deaths and migrations, we used the Cause of Death and Migration registries. If the patient died, emigrated, or was diagnosed with schizophrenia during the second (treated) period, the follow-up was censored at this time. This was done also when a mood stabilizer was dispensed to the antidepressant monotherapy group during the treated period. To allow for assessment of both acute and longer-term effects, interaction terms with split follow-up time (0–3 months, 3–9 months) were included in the statistical model (

32). In a second analysis, medication with a mood stabilizer was added as an additional interaction term to determine differences in effects depending on concurrent mood stabilizer use.

The study was approved by the regional ethics committee in Stockholm.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all patients included in the study. The patients’ mean age was 51.6 years (SD=17.0), and a majority (60.8%) were women. The types of antidepressants dispensed, along with the numbers of patients receiving them, are listed in

Table 2.

Overall Effects of Antidepressants on Risk of Mania

In all patients with bipolar disorder treated with an antidepressant, not taking into account any concurrent mood stabilizer treatment, we observed no increased risk of mania within the first 3 months of treatment (the hazard ratio for the 0- to 3-month period was 0.91, 95% CI=0.69, 1.21; n.s.). For the period 3–9 months after start of treatment, we observed a decreased risk of mania (hazard ratio=0.68, 95% CI=0.50, 0.92; p=0.01) (

Table 3).

Effects of Concurrent Mood Stabilizer Medication

Among all patients treated with an antidepressant, 1,117 were on antidepressant monotherapy and 1,641 were on concurrent treatment with a mood stabilizer (

Table 4). Thus, contrary to clinical guidelines, a substantial portion of the bipolar patients received prescriptions for an antidepressant as monotherapy. The rate of mania and the number of mania diagnoses were higher in the group treated with a mood stabilizer and an antidepressant than in the antidepressant monotherapy group. This is most probably because the patients treated mood stabilizers had a more severe bipolar disorder to start with. Nevertheless, when we analyzed the effect of antidepressant monotherapy, the risk of mania was significantly increased in the acute period (hazard ratio=2.83, 95% CI=1.12, 7.19; p=0.028), but not in the longer term (hazard ratio=0.71, 95% CI=0.23, 2.26; n.s.).

By contrast, among patients receiving a concurrent mood stabilizer medication, the risk of mania was unchanged in the acute period after initiation of antidepressant treatment (hazard ratio=0.79, 95% CI=0.54, 1.15, n.s.) and was significantly decreased in the longer term (hazard ratio=0.63, 95% CI=0.42, 0.93, p=0.020).

Discussion

Previous research has suggested that antidepressant treatment of depressed patients with bipolar disorder can induce a switch to mania (

13–

17), and there is controversy as to whether concurrent use of a mood stabilizer eliminates this risk. In this population-based study, we demonstrate that the risk of manic switch after treatment with an antidepressant among patients with bipolar disorder was largely confined to those who were on antidepressant monotherapy.

Our finding that antidepressant treatment is acutely associated with manic episodes when used alone in bipolar patients is in line with reports from clinical trials with antidepressant monotherapy (

13–

17,

32). This study thus lends further support to the need for caution when using antidepressant monotherapy to treat bipolar depressive episodes because of the risk of treatment-emergent mania, an approach that is in accord with recent recommendations from the International Society for Bipolar Disorders on antidepressant use in bipolar disorder (

33).

Results from previous studies on the protective effect of concurrent mood-stabilizing treatment have been inconsistent. Our finding that antidepressant treatment does not increase the rate of mania when combined with a mood stabilizer is consistent with reports from Bottlender et al. (

23) and Henry et al. (

24), who found a significantly decreased risk of switching when a mood stabilizer was coadministered with a tricyclic antidepressant compared with a tricyclic alone. However, Boerlin et al. (

14) and Young et al. (

26) compared mood-stabilizer treatment to antidepressant treatment in a small number of patients and did not find any difference in manic symptoms between the groups (

14,

26). These inconsistencies are very likely due to limited sample sizes; previous studies included less than a total of 100 patients, and some less than 50, which were then split into two groups. With 1,641 patients in the combined group, our study provided greater power to detect the effect of antidepressants taken in combination with mood stabilizers.

Our findings are at odds, however, with those of a large meta-analysis by Tondo et al. (

27), who found that mood stabilizers did not protect against treatment-emergent mania during antidepressant treatment. While their meta-analysis included several studies adding up a large number of patients, it could not control for confounding by indication, as the authors discuss.

One would expect that patients treated with a mood stabilizer in combination with an antidepressant would have a more severe disorder than patients treated with a mood stabilizer alone, which is likely to obscure any potential protective effect that a mood stabilizer has on the switch rate. In the present study, we circumvented the risk of confounding by indication by using a within-individual design, reducing confounding caused by differences in disorder severity.Whether antidepressants should be prescribed to treat depression in bipolar disorder has been debated for decades. At the core of this debate is weighing the clinical benefit of antidepressant treatment against risk of worsening the illness by inducing mania or instability. Our study suggests that use of an antidepressant in conjunction with a mood stabilizer does not increase the risk of mania. This is important because treatment options for bipolar depression are urgently needed; patients with bipolar disorder spend most of their time in depressive episodes, and depressive symptoms are the leading cause of impairment and morbidity in bipolar patients.

We used registry data in this pharmacoepidemiological study. The strengths of this approach compared with clinical trials include the large number of study subjects, which confers greater statistical power, and the inclusion of data from most of the patients of interest within a population. A registry-based study includes patients who for various reasons would have been excluded from or would not have volunteered for a clinical trial. However, observational studies entail a risk of selection effects. This risk is even more pronounced in pharmacoepidemiological studies, where confounding by indication is a major hurdle. Treated patients are likely to differ from nontreated patients in symptom severity. This is well illustrated in our study, where the rate of mania in the group of patients on a concurrent mood stabilizer was higher overall than in the antidepressant monotherapy group (2.4–6.8 times, depending on the period compared). This is not surprising, as the patients previously treated with a mood stabilizer received this treatment precisely because they were more prone to manic episodes than the patients with no prior mood stabilizer treatment. We therefore employed a within-individual design, in which the rate of mania is compared between a non-treatment period and a treatment period in the same patient. This reduces the confounding due to disorder severity, genetic makeup, and early environmental factors that can be expected between those who receive a prescription for a mood stabilizer and those who do not.

Another potential limitation of registry-based studies is diagnostic specificity. The bipolar diagnoses in the National Patient Register have been validated, however, and an algorithm has been constructed that yields a positive predictive value of 0.92 (

30). The diagnoses of acute mania have not been validated. Nevertheless, the outcome of interest in this study—a diagnosis of acute mania in a patient with known bipolar disorder—is likely to be reasonably valid. It should be noted, however, that this outcome captures the severe end of the mania spectrum, where symptoms lead to an outpatient visit or a hospitalization; milder hypomanias that do not lead to contact with the health care system will not be captured in this study.

Another limitation of this study is that bipolar II disorder is not a listed ICD diagnosis in the National Patient Register. Hence, we could not specifically study bipolar II disorder with respect to risk of treatment-emergent mania or the potential protective effects of mood stabilizers. Given the fact that bipolar II disorder is at least as common as bipolar I disorder, additional research in this area is warranted. Also, our study does not provide information about the effectiveness of antidepressants in bipolar depression, nor about patients’ adherence to drug treatment; we have no information on whether a patient actually used the dispensed medication. Furthermore, we could not assess the effects of specific classes of antidepressants, as the groups were too small to permit meaningful comparisons. Finally, we censored the follow-up for individuals in the monotherapy group if a mood stabilizer was dispensed. The indications for these mood stabilizer prescriptions are unknown; it could be the start of prophylactic treatment in a stable phase or a late safety measure to add a mood stabilizer to the antidepressant treatment. However, there is also the possibility that the mood stabilizer was prescribed because of treatment-emergent hypomania or mania that was not recorded; in this case, censoring will yield a lower risk of mania after antidepressant treatment than is actually the case.

Conclusions

While we found an increased risk of manic switch among patients with bipolar disorder on antidepressant monotherapy, we did not find an increased risk of manic episodes in the short or longer term for patients treated with an antidepressant and a concurrent mood stabilizer. Even though current practice guidelines suggest treatment with antidepressants only in combination with mood stabilizers in bipolar patients, and the effectiveness of antidepressants in treating bipolar depression is disputed, the clinical practice looks different. In our study, almost 35% of the patients were on antidepressant monotherapy, and 70% of all bipolar patients had at least one dispensation of an antidepressant over a 5-year period. Thus, our results are important for future guidelines, but probably even more important for reminding clinicians of the importance of these guidelines.