Introduction

Upon full implementation of the Affordable Care Act, it is estimated that more than 32 million Americans will become insured and gain access to mental health and substance abuse services at parity (

1). Despite considerable gains in the number of medical school graduates entering the field of psychiatry over the past ten years, it has become clear that the workforce of psychiatrists is not large enough, acting alone, to meet the needs of patients (

2,

3).

The integration of primary and behavioral healthcare provides opportunities for psychiatrists interested in reaching a greater population of patients with their skills and expertise. In integrated care settings, the psychiatrist provides medical advice in the form of a consultation to the primary care provider for management of a patient’s mental health concerns. These recommendations may or may not be based upon meeting with the patient in person or a review of the medical record. Working along with other behavioral health providers and primary care providers, psychiatrists are able to extend their services to a larger group of patients in comparison with practicing as the direct care provider.

There are several models for psychiatric consultation to primary care providers, including co-location in the same facility, the IMPACT (Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment) model, and telephonic psychiatry consultation as in the MCPAP (Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project). The models may vary; however, the principles of integrated care are the same, which is to provide a comprehensive treatment structure where-by primary healthcare providers interact with a number of other providers, including psychiatrists, in the overall care and treatment of their patients.

For psychiatrists considering future roles in integrated care systems, it is important to clarify malpractice liability when providing advice about care for patients for whom the psychiatrist may not be the primary prescriber. To the extent of the authors’ knowledge, there are no known cases of malpractice brought against collaborative care treatment programs (

4,

5). This resource document provides background information on medical malpractice cases, defines the doctor-patient relationship, distinguishes the different forms of consultation offered to primary prescribers, describes the duty of the psychiatrist across the spectrum of roles on a patient care team, and, finally, makes recommendations to reduce the risk of malpractice issues. Bear in mind that issues regarding liability may not always be clear; however, this document is intended to provide a framework for some of the issues to consider when working in an integrated practice.

Background on Medical Malpractice Cases

In most medical malpractice cases, the patient/plaintiff or delegate asserts a claim for negligence against the provider. Briefly, medical malpractice is professional negligence by a doctor, nurse or other healthcare worker that causes physical or emotional harm to a patient. This can result from something the provider did or otherwise failed to do.

There is a four-prong analysis used in medical malpractice negligence cases to prove medical malpractice negligence against a provider. In order for a plaintiff to be successful he or she must prove that all four elements exist. If the defendant/healthcare provider can establish that one or more of the elements does not exist, then the plaintiff would not prevail. The elements are as follows:

•.

Duty: the healthcare provider must have owed a duty to the patient. Concerning a case specifically against a physician, a doctor-patient relationship must exist for there to be a duty. (See below doctor-patient relationship).

•.

Breach of Duty: The healthcare provider who had the duty of care for the patient must have failed in his/her duty by not exercising the degree of care or medical skill that another healthcare professional, in the same specialty, would have used in a similar situation. Most often expert testimony defines what the appropriate standard of care would be.

•.

Causation: The breach of the healthcare provider’s duty was causally related to the patient’s injury.

•.

Damages: The patient must have suffered an injury (physical and/or emotional).

Doctor-Patient Relationships

In order for there to be a legal duty, there must first be an existence of a doctor-patient relationship (

6). In other words, before a psychiatrist may be found liable for an act of medical malpractice, it is essential that a doctor-patient relationship exist (

7). This relationship may result from a number of situations, and it is not necessarily dependent upon the existence of a formal or express agreement (

8). Generally, however, the psychiatrist must take some affirmative step, such as consenting to treat a patient, for the doctor-patient relationship to be established (

9). Courts and/or juries determine whether a doctor-patient relationship exists, and this is often difficult to ascertain because many gray areas exist. In the simplest form, the physician and the patient both agree to examination, diagnosis, prescribing, and/or treatment. However, a doctor-patient relationship can potentially be established even if the physician sees the patient on one occasion in consultation.

Some courts consider factors in determining whether a physician-patient relationship exists.

Courts have created factors to determine whether a physician-patient relationship exists. Some of which may include:

•.

The existence of a relationship between the consulting physician and the facility providing care that would require the consultant to provide advice.

•.

The degree to which the consultation given affected the course of treatment.

•.

The relative ability and independence of the immediate care provider to implement his or her own decision (

10). [

Check with your own state to determine what the courts view as a physician-patient relationship as it may vary between states.]

Courts may also impose liability under the doctrine of

Respondeat Superior, in instances where a physician may have an authority or supervisory role over the patient care without direct provision of care. For example, a psychiatrist who agrees to supervise trainees, licensed clinicians, nonmedical therapists or practices within a group setting may be held liable for the actions of others within the scope of their practice (

11). So, while a psychiatrist may have no direct involvement with a patient, if there is a leadership role, there may be vicarious liability. [

Respondeat superior is when an employer is held vicariously liability for the acts of its employee/servant which were committed within the scope of his/her employment] (

12).

Psychiatrists should also be aware of any contractual agreements to provide care for patients within the institution or agency where they are employed. This is also particularly important to consider when entering into partnerships with other physicians in medical practice groups. Medical practice groups may vary in structure and organization, and therefore, it may be helpful to seek legal counsel to review contractual agreements. It is important to note that once a doctor-patient relationship is established, then the doctor owes a duty to the patient to provide treatment which complies with the standard of care. This duty arises irrespective of reimbursement for services.

Consultations

Consultations frequently occur in all types of practice, including psychiatry. Physician liability may depend upon whether the physician engaged in a “formal” consultation rather than an informal consultation often referred to as a “curbside” consultation. There are, however, also “gray” areas that exist where the physician’s role is not clearly defined. Courts and juries look at many factors when determining liability. It is important, however, to understand that a physician may be held liable when they use their clinical expertise to advise a colleague on a recommended course of treatment.

In general, there are two main ways of providing consultations on patient care:

1. Formal Consultation:

a.

Occurs when a treating physician directly requests the written and/or verbal opinion of a consulting physician.

b.

A formal consultation results in the creation of a physician-patient relationship and a legal duty to the patient.

c.

This could be accomplished through a variety of methods, including face-to-face interview of the patient or telephone assessments.

d.

The consultant typically documents in the patient’s medical record (

13). The psychiatrist and/or the psychiatrist’s employing clinic/ agency/healthcare facility are receiving a fee for services rendered in the care of the patient.

e.

May prescribe medications per arrangement with requesting physician.

2. Informal (Curbside) Consultation (14)

a.

Generally occurs when a treating physician seeks the informal advice of a colleague concerning a course of treatment for a patient.

b.

The patient’s identity is rarely known to the consultant (

15).

c.

The psychiatrist does not usually perform a face-to-face interview/assessment of the patient.

d.

The psychiatrist usually provides no written documentation within the patient’s medical record.

e.

The psychiatrist receives no compensation for services rendered in the care of the patient. However, the absence of compensation or direct examination does not alleviate the psychiatrist’s duty to provide care within the standard of care.

f.

The treating physician remains in charge of the patient’s care and treatment.

Note: There are a number of published cases involving curbside consultations. Whether liability attaches is dependent upon the specific facts of a case, applicable rules, regulations, caselaw within your state, and the court’s determination. Outcomes on how the court decides or whether liability attaches may vary between states (

16,

17).

There are some key questions to consider when providing any form of consultation:

•.

What is the contractual relationship between the consulting psychiatrist and the clinic/agency/ healthcare facility itself?

•.

Are there others making decisions about the clinical care of the patient? Do not assume that you and the requesting physician are the only providers and/or prescribers.

•.

What is the system for addressing patient care emergencies, including threats of violence?

•.

Who is responsible for various aspects of the patient's care, and what are the coverage arrangements for each clinician in their absence?

The Role of the Psychiatrist in Integrated Care Settings

As mentioned previously, there are a variety of models for practicing in integrated care settings, including split care in which several providers manage the mental health care of the same patient. Aspects of split care are usually referred to in the context of psychiatrists providing medication management with a therapist or other clinician providing additional services. In these collaborative arrangements, treatment may be provided by the primary care provider, behavioral health provider, a midlevel provider, as well as the psychiatrist.

Note: Be aware of applicable state regulations and ethical guidelines when working with other providers including nonmedical therapists. Consult the APA

Resource Document on Guidelines for Psychiatrists in Consultative, Supervisory, or Collaborative Relationships with Nonphysician Clinicians (

18).

In a traditional split treatment context for psychiatrists, the basic roles assumed may include one, or a combination of the following:

1. Supervisory Role (typically the highest liability risk of the three roles)*:

a.

The psychiatrist is responsible for the overall care of the patient.

b.

Decisions and actions are under the psychiatrist’s direction.

c.

The psychiatrist remains ethically and medically responsible for the patient’s care as long as treatment continues under his/her supervision.

d.

The psychiatrist has the ability to alter treatment and give direction to clinicians involved in the care of the patient.

e.

The psychiatrist should be aware of the other provider’s level of experience, training and competency in determining oversight of the other provider.

Note: Liability for supervisors may vary between jurisdictions. For example, the Vermont Supreme Court recently considered the issue of physician liability when acting in a supervisory role. The Court held that a doctor was not held liable for his PA’s misconduct. In its opinion, the court noted that there are 39 scenarios in which a physician can be held professionally responsible, and it does not include the misconduct of a PA, but focuses instead on a physician’s acts, namely actions that bear on a physician’s fitness and ability to practice in the state (

19).

2. Collaborative Role (typically the most complex of the three roles)

a.

Psychiatrists and primary care providers may work along with one another while managing both somatic and mental health concerns.

b.

Mutual shared responsibility for the patient with an agreement upon the diagnosis, anticipated therapies and risk that derive from the patient’s diagnosis and treatment.

c.

Independent and interdependent duties for ongoing risk assessment.

d.

The psychiatrist may or may not provide direct patient care. However, there is no supervisory relationship suggested between the prescribers when treating patients with mental illness. Instead, the clinicians collaborate in the care and treatment of the patient.

e.

Each physician has a shared responsibility to tell the other about any substantive change in the patient and/or treatment.

f.

Each physician will provide direct examination of the patient.

3. Consultant Role (typically the least liability of the three):

a.

The patient’s treatment will be dictated by some one other than the psychiatrist. As above, the psychiatrist may perform the tasks consistent with Formal Consultation. There may be no continuing duty to care for the patient, however, the role should be made clear between the physicians and, where applicable, the patient.

b.

There is no supervisory relationship suggested when treating patients with mental illness.

c.

The psychiatrist offers advice on a “take it or leave it basis.”

d.

The psychiatrist remains outside the decision-making chain of command.

The Blended Role of the Psychiatrist in Integrated Care Settings

In response to an increasing need for mental health services, there is growing a shift from independent/ autonomous behavioral health and primary care practices to collaborative care practice models, which include mental health specialists (e.g. psychiatrists, psychologists, or counselors) within primary care clinics (

20). This approach, often referred to as “co-location,” has several benefits for patients. First, the proximity between the psychiatrist and primary care provider may lead to increased awareness of mental health management with the primary care setting through “informal consultation,” and where appropriate, referral to an accessible psychiatrist for formal consultation. In the latter, both the psychiatrist and the primary care provider are involved in the direct provision of care. However, the psychiatrist may only be involved for a limited time and not involved in the on-going care of the patient.

In addition, co-location may help minimize the potential that the patient may not follow-up with a separate, more distant specialist. Co-location, however, does not necessarily imply an obligation for the primary care provider to communicate with the psychiatrist about the mental health of patients or make referrals to the psychiatrist. This limitation has given rise to new treatment paradigms for improving collaborative care.

Examples of Integrated Care Models

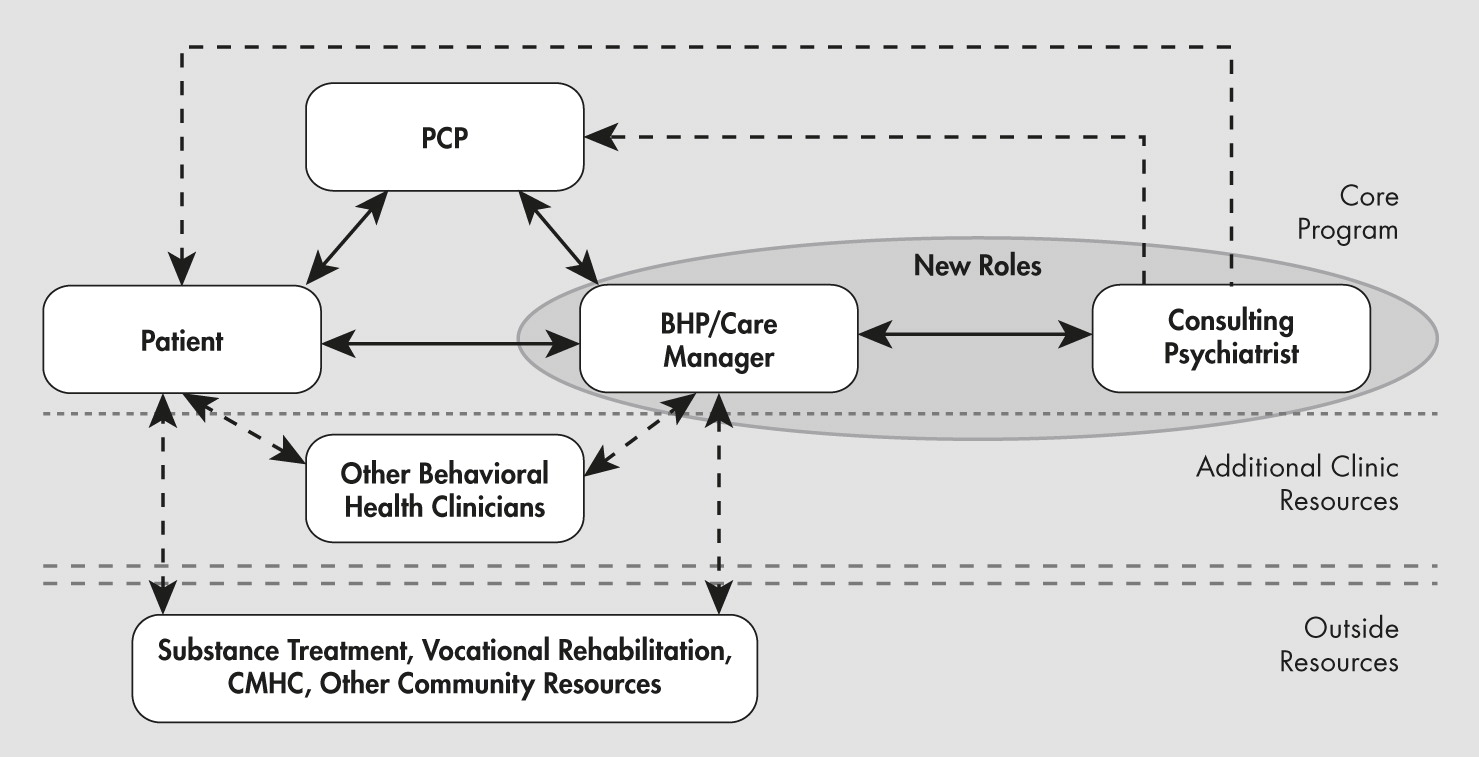

As the role of the psychiatrist in integrated care settings is continually evolving, so is the approach to collaborative care. The IMPACT model is frequently referred to and has a well thought out design that weaves together key roles for the core team members, including the primary care provider, the behavioral health provider (e.g. psychologist, social worker, nurse), and the psychiatric consultant (

Diagram 1) for the treatment of depression. The nature of the role of the consulting psychiatrist in this model includes “curbside” or informal consultation (approximately 95% of patients), psycho-education, limited formal consultation (approximately 5% of patients), and caseload-based supervision of behavioral health providers. In one of the largest successful treatment trials using the IMPACT model, the initial treatment interventions were delivered by primary care providers (PCP) along with behavioral health providers (BHP) trained specifically in the management of depression (

21). The psychiatrist met with the BHP on a regular basis to review cases, clarify diagnoses, and relay directions to the PCP to suggest changes in the treatment. If participants had not responded to treatment as expected, the psychiatrists recommended changes in the treatment plan, which perhaps included a face-to-face evaluation. In this model, several types of relationships can exist between the psychiatrist and the other members of the patient’s care team. While the relationship between the psychiatrist and the BHPs could be considered supervisory, the relationship with the PCP could be considered collaborative and/or consultative. (See sections Back ground on Medical Malpractice Cases and Doctor-Patient Relationships). Therefore, it is essential for the psychiatrist to clarify their role including contractual obligations for consultations, communication of patient data, and the provision of care in any treatment setting.

In the previously mentioned MCPAP model, the PCP may place a telephonic consultation to a child psychiatrist located in a central facility regarding a mental health question or concern pertaining to particular patient (

22). The call may involve a general question regarding the diagnosis and treatment of a specific disorder, use of a particular medication, use of mental health screening tools, or about questions pertaining to resources in the area. The following scenarios may result from the telephone consultation. The child psychiatry consultant may respond by either answering the PCP’s question over the telephone; recommend a face-to-face evaluation in order to answer the PCP’s question; refer the PCP and/or the family to the mental health care coordinator for information about resources in the community; or recommend that the patient see the MCPAP therapist for evaluation and/or interim treatment. In these types of relationships, the duty of care remains with the PCP. In these cases, although the consulting psychiatrist does not communicate with the patient, review the patient’s medical chart, or directly treat the patient during telephonic consultation, the consultant should provide recommendations for reasonable care.

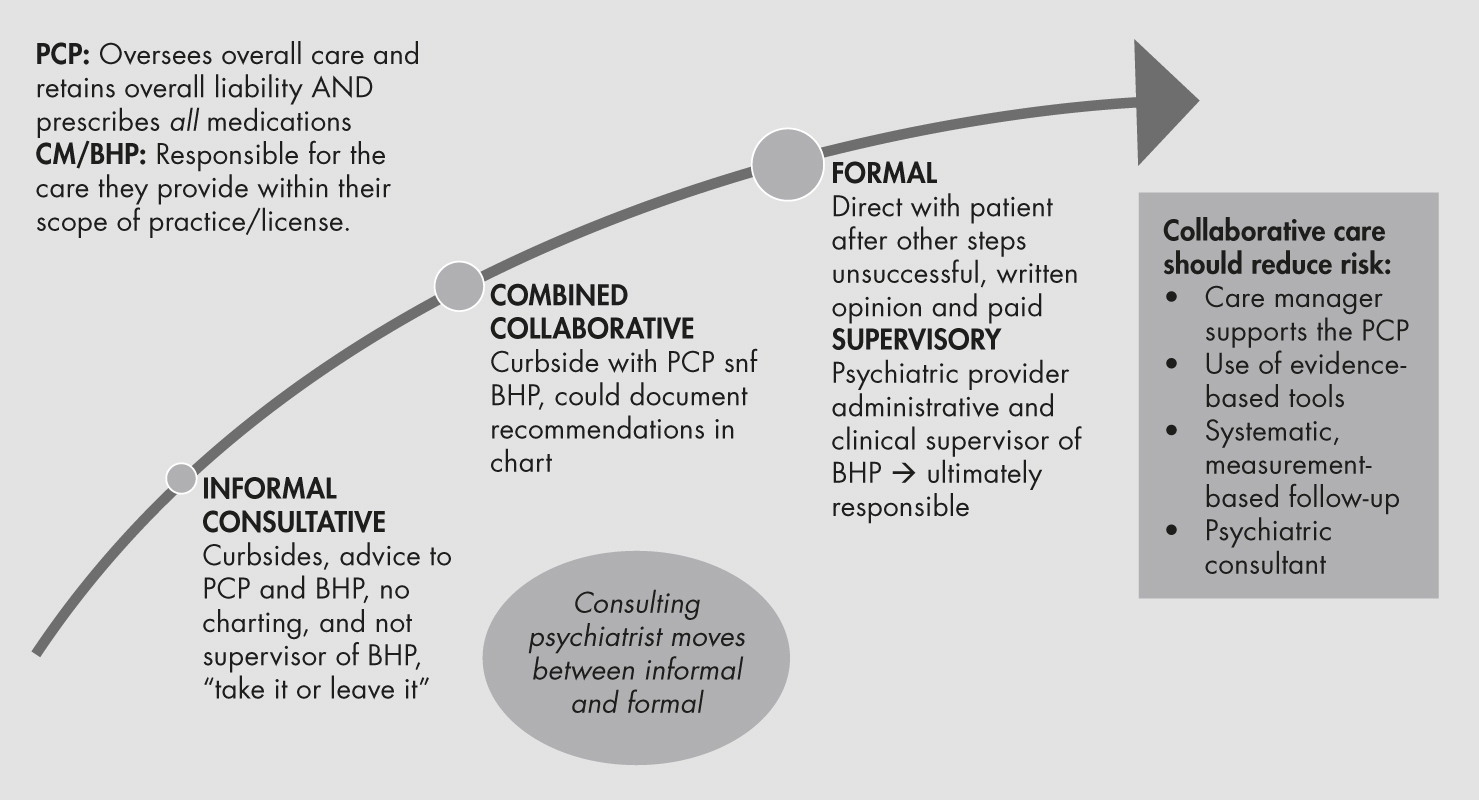

The psychiatry consultant’s role may include key aspects of both formal and informal consultation and varying aspects of split treatment in many current models of care. For example, in the IMPACT model, the psychiatry consultant begins the treatment process providing

informal consultation to the PCP and BHP. This may evolve to the need for a

formal consultation if psychiatric treatment is necessary beyond what the treatment team can provide. Telephonic consultation in the MCPAP model also starts with the

informal consultation line of reasoning, but using televideo or telephonic consultation for the most difficult patients may begin to cross over into the realm of a

formal consultation (

Diagram 2).

The more complex intersection of care occurs when the nature of the psychiatry consultant’s contribution to the overall care of patients may encompass varying roles within the integrated care setting. In other words, the psychiatrist role may include any or all of the three traditional split treatment roles. While the PCP assumes responsibility for the overall care of the patient with no assumption that the psychiatrist has this duty, in some organizations, the psychiatrist could be in an administrative or supervisory role with the BHP or MCPAP therapist. When the psychiatry consultant completes a formal consult and makes treatment recommendations, he/she may be functioning in a collaborative or consultative role with the PCP. However, the PCP, who may have primary responsibility for the treatment as mentioned above, may also decide if the psychiatry consultant’s recommended treatment course will not be followed. As such, the psychiatrist’s role in patient care should be addressed in the contractual agreement.

In many integrated care models, psychiatrists are encouraged not to order any medications that they have recommended for patients as this is a decision for the PCP to make, consistent with their overall supervision of the patient’s care (

23,

24). Again, the role of the consultant should be discussed in contractual agreements. As the psychiatrist’s role may differ depending on the case, his/her role and should be clearly identified to the other providers. Where indicated, the psychiatrist should also clarify the extent of their involvement in the case and level of interaction with the patient. An example of this would be as described below by the Mental Health Improvement Program (MHIP) of Washington State, which functions based on the IMPACT model (

25). This sample disclaimer may be attached to any note referencing

informal consultations:

“The above treatment considerations and suggestions are based on consultations with the patient’s care manager and a review of information available in the Mental Health Integrated Tracking System (MHITS). I have not personally examined the patient. All recommendations should be implemented with consideration of the patient’s relevant prior history and current clinical status. Please feel free to call me with any questions about the care of this patient.”

In effect, the psychiatry consultant can opt for an arrangement whereby they provide informal consultations (at least 95% of the time in some models) and a consultative role with the other team members (

Diagram 2) (

26). However, this is not always practical and is not a guarantee of avoiding malpractice litigation.