The first two pilot studies reporting an oxytocin effect in borderline personality disorder were published in 2011. Simeon et al. (

117) found that oxytocin may attenuate dysphoric emotional and salivary cortisol responses to social stress in a small, mixed-gender sample of 14 patients with borderline personality disorder and 13 healthy volunteers who received either oxytocin or placebo. Contrary to previous studies, no effects were observed in the healthy sample. The results of a second study by the same group (

118), again consisting of 14 patients with borderline personality disorder and 13 healthy volunteers, indicate that in patients, oxytocin may decrease trust and the likelihood of cooperative responses in a financial trust game. The finding of reduced financial trust in patients after oxytocin administration was supported by a study by Ebert et al. (

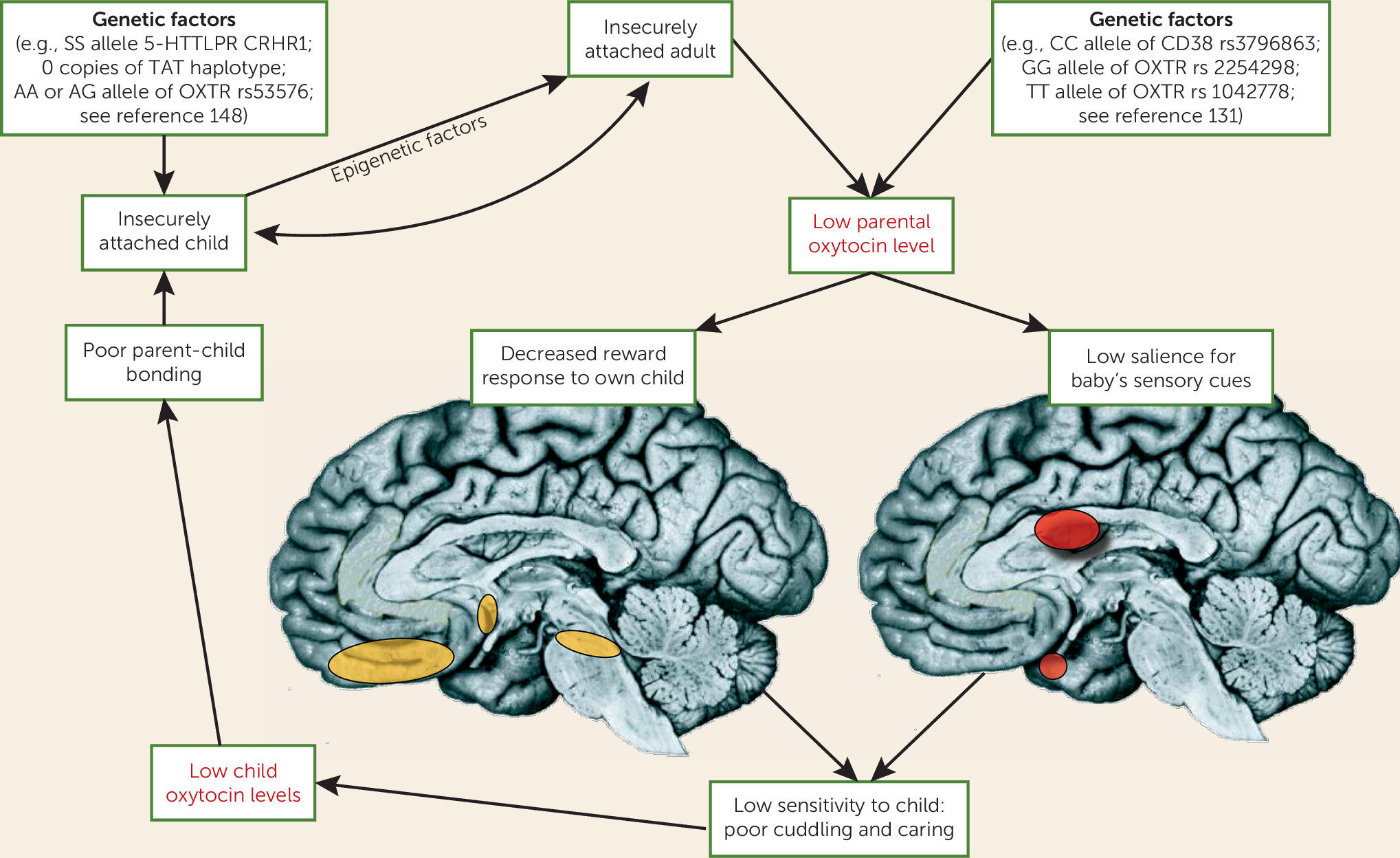

119) in a cross-over design with 13 patients with borderline personality disorder and 13 healthy volunteers. Despite the small sample sizes, which limit the interpretation of these studies, the results suggest that oxytocin may have different effects on patients with borderline personality disorder, depending on chronic interpersonal insecurities, and possible differences in the oxytocin system regulation. This is in line with an “interactionist model” proposed by Bartz et al. (

87), who emphasized the moderating role of contextual factors and interindividual differences in oxytocinergic modulations of social cognition and behavior. For the study of borderline personality disorder, interindividual differences in rearing conditions, including early-life maltreatment and attachment style (

120), appear to be of particular significance, as more than 90% of patients with borderline personality disorder show insecure attachment classifications, with a high frequency of unresolved attachment representations. Interestingly, an additional data analysis in one of the above-reported studies (

118) revealed that across patients with borderline personality disorder and healthy volunteers, oxytocin increased cooperative behavior for high-anxious, low-avoidant participants but decreased cooperation for high-anxious, high-avoidant participants. Differences in acute stressors (

121); comorbid disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (

122); treatment experiences; levels of endogenous oxytocin (see below), vasopressin, cortisol, and/or testosterone (

30); and variations in the activity or function of the oxytocin and vasopressin receptor genes may be particularly relevant modulators of oxytocin effects.

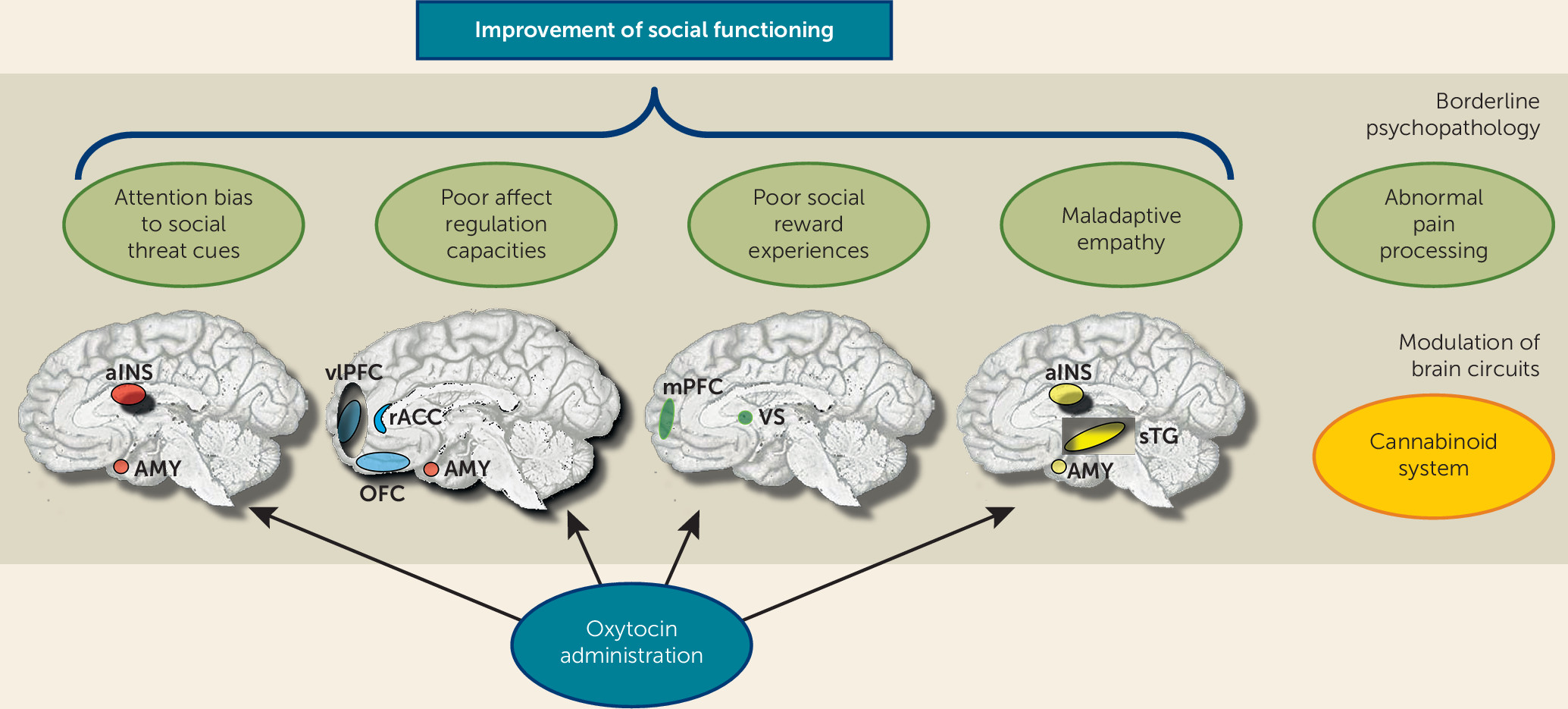

To date, two studies have investigated the effects of intranasal administration of oxytocin on the emotional stimulus processing. Brüne et al. (

123) compared 13 patients with borderline personality disorder and 13 healthy volunteers, using a dot-probe task to examine attentional biases to happy and angry faces. Oxytocin was found to attenuate avoidant reactions to angry faces in patients with borderline personality disorder. Recently, our group provided first evidence that oxytocin has the potential to diminish threat hypersensitivity in borderline personality disorder (

124). In a placebo-controlled double-blind group design, 40 female patients with borderline personality disorder and 41 healthy women took part in a combined eye-tracking and fMRI emotion classification experiment. In this task, patients showed more and faster initial fixation changes to the eyes of very briefly presented (150 ms) angry faces, which was associated with increased activation of the posterior amygdala. Oxytocin reduced posterior amygdala hyperactivity as well as the attentional bias toward socially threatening cues (i.e., the eyes of angry, but not fearful or happy faces) in patients.

Hence, there is limited evidence for beneficial effects from exogenous oxytocin administration in borderline personality disorder, with reports of reduced amygdala-driven threat hypersensitivity and decreased avoidant behavior. Nevertheless, much more research is needed to address moderating influences of gender and interindividual differences in trait variables, attachment style, and social functioning. It also remains unclear whether borderline personality disorder is related to dysfunction in the oxytocin receptors that may yield greater binding of oxytocin to vasopressin receptors and hence could also lead to adverse effects if administered in larger doses or on a regular basis. These questions need to be addressed in animal models and large genetic studies.