The increased risk of psychopathology in the offspring of depressed parents is widely known. The long-term consequences through the full age of risk based on longitudinal data are not. We report results from a follow-up of up to 30 years of biological offspring of depressed and nondepressed parents. Previous reports of these families occurred at 10- and 20-years follow-up when they were primarily adolescents (

1) or young adults (

2). The purpose is to determine whether the risk of psychopathology, morbidity, and mortality in offspring of depressed parents continues as they mature.

The high rate of psychopathology and impaired functioning in the offspring of depressed parents compared with nondepressed parents is one of the best replicated findings in psychiatry (

3–

9), showing at least a two- to threefold increased risk of major depression depending on how the phenotype is defined and how the control group is selected. There have been follow-ups of the offspring to determine continuity in well-designed studies. The longest studies have been 16 and 20 years (

10,

11). However, the offspring were studied from birth so that outcomes did not cover the full age of risk.

There have also been longitudinal studies of depressed or anxious patients, independent of parental diagnosis (

12–

15), the longest being 44 years (

16). However, to our knowledge, no published studies of high risk have followed offspring into adulthood. The longer follow-up through the full age of risk for major depression allows estimates of age-specific and cumulative lifetime rates of psychiatric disorders, morbidity, and mortality in samples known to be at risk.

Method

In the original study, probands (generation 1=G1) with moderate to severe unipolar major depressive disorder were selected from outpatient specialty settings for the psychopharmacologic treatment of mood disorders. Nondepressed probands were selected, at the same time, from an epidemiologic sample of adults from the same community. They were required to have no lifetime history of psychiatric illness, as indicated by several interviews. Full details, summarized here, can be found elsewhere (

1,

2,

17,

18). We report data from wave 5 or 6 (about 30 years after the first two waves). The procedures were kept similar across the waves, with few exceptions, to avoid introducing methods bias. Across all waves, the proband, spouse, and offspring were interviewed by independent interviewers who were blind to the clinical status of the previous generations and the subject’s previous history. Two spouses of probands (G1) in the low-risk group subsequently developed major depression between waves 1 and 2, as determined by best-estimate diagnosis. These families were reclassified as having depressed probands. The subjects were all European Caucasian to reduce heterogeneity for future genetic studies, as was the custom when the study began.

Study Groups

The study began in 1982, and the last interviews were completed in 2015 (approximately 33 years later). There were six waves of interviews, at baseline and 2, 10, 20, 25, and 30 years. The 25-year interview had a small sample recruited for MRI studies. In order to obtain the largest sample followed, we included any biological offspring (generation 2=G2) who entered the study at wave 1 or 2 and was assessed at wave 5 or 6.

Two hundred sixty-three offspring from 91 families were interviewed at wave 1 or 2 and became the cohort for these analyses. During the course of the study, we learned that one offspring was adopted, one was ineligible due to Down’s syndrome, and 12 offspring died. The two ineligible offspring were removed from the denominator. Data on outcome over about 30 years were available on 159 offspring (159/261 [61%]). The responders (N=147) did not differ from nonresponders (N=104) who were seen at wave 1 or 2, and were still alive at wave 6, on age, gender, risk group, or lifetime major depression at last interview.

All interview waves were approved by the institutional review board at New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University. Written informed consent was obtained from adults, and written consent was obtained from parents with assent from minors.

Assessments

The assessments were described previously (

1,

2). The diagnostic interview across all waves was the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Lifetime Version (SADS-L) for adults and the child version (Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children [K-SADS-E]) modified for DSM-IV when subjects were between ages 6 and 17 (

19,

20). The Global Assessment Scale (GAS) was completed by best-estimate at each wave (

21). This assessment, made on a 0- to 100-point scale, provides an overall estimate of the person’s current functional adjustment based on all available information. A child’s version, the C-GAS, was used when the offspring were between ages 6 and 17 (

22). Lower scores on the GAS or C-GAS indicate more overall impairment. Data on medical illnesses were collected using a standard medical checklist that includes 57 conditions and asking whether a doctor told the subject that he or she had the condition and whether medication was taken for it. This information was collected at each wave from the subject and/or, in the case of minors, from the parent about the child. The data from all waves were pooled to create a lifetime history of medical conditions. Ambiguous reports of medical problems were coded during the best-estimate process by a physician.

Information on mortality was obtained by report from one or more relatives and confirmed by the Social Security Death Master File (

https://www.ssdmf.com) and/or an online obituary search engine (tributes.com, genealogybank.com, and/or legacy.com). Cause of death was obtained primarily by family informant, and if unknown, by death certificates or newspaper articles. No information could be obtained on three of the 261 subjects. All three subjects were high-risk offspring.

Interviewers and Best-Estimate Procedures

The diagnostic assessments were administered by trained doctoral- or master’s-level mental health professionals who were blind to the clinical status of the parents and to previous history information. Training procedures remained the same across waves (

1,

2). Multiple sources of information were obtained, including direct and informant interviews and medical records when available. Final diagnosis of all generations was based on the best-estimate procedure (

23). At wave 5, two experienced clinicians (D.P. and H.V.) who were not involved in the interviewing, independently and blind to the diagnostic status of the previous generation, reviewed all the material and assigned DSM-IV diagnoses and a GAS or C-GAS score. The two diagnosticians corated 178 randomly selected cases from all generations. Kappa scores for inter-rater reliability were good to excellent: major depressive disorder, 0.82; dysthymia, 0.89; anxiety disorder, 0.65; alcohol abuse/dependence, 0.94; and drug abuse/dependence, 1.00. At wave 6, best-estimate diagnoses were all done by D.P.

Statistical Analysis

Preliminary analyses of group differences in mean values for continuous outcomes by parental depression were tested using the t test; ordinal outcomes were tested with the Kruskal-Wallis chi-square test; and categorical outcomes were compared by the chi-square test. Continuous outcomes were analyzed using linear regression with the offspring outcome, such as the C-GAS score, as the dependent variable and parental depression as the predictor variable (

24). Cross-sectional categorical outcomes (e.g., treatment variables) were analyzed using logistic regression. Age and sex of offspring were considered a priori to be confounding variables and were retained in every model. These analyses were performed by applying a generalized estimating equations approach (

25) by means of the GENMOD procedure in the SAS software package (

26), to estimate parameters and to adjust for potential nonindependence of outcomes for offspring from the same family. Survival analysis techniques adjusting for correlated survival times were used to estimate 1) the age-specific incidence rates of psychiatric disorder in 10-year intervals by using life-table methods and 2) cumulative lifetime rates of major depressive disorder in high- versus low-risk offspring by gender, by means of a modified Kaplan-Meier method (

27). Cox proportional hazards regression models (

28) modified to adjust for clustered data were used, following the approach described by Lin and Wei (

29). This approach consists of using a robust sandwich covariance matrix estimate to account for the intracluster dependence and was used to estimate the relative risks of disorder by parental depression status while controlling for potential confounding variables, by means of the SUDAAN software package. The adjustment for clustered data was necessary to account for potential nonindependence of outcomes for offspring from the same family. The mean number of offspring per family was 2.1 (SD=1.0), the median 2, and the range 1–5. None of these descriptives differed by risk group.

Results

Characteristics of Offspring

At the 30-year follow-up, the offspring of depressed and nondepressed probands (G1) did not differ by gender (57% female), mean age at first (19.4 years [SD=6.9]) or last (47.4 years [SD=7.1]) interview, mean number of interviews (mean=5.0 [SD=0.9]), or response rate at waves 3 or 4 (

Table 1). The study was carried out over 33 years (1982–2015), and the mean number of years in the study was 28.1 (range=20.0–32.3).

Cumulative and Age-Specific Rates of Psychiatric Disorders

During the 30-year follow-up, the offspring of depressed parents, compared with nondepressed parents, had about a twofold increased risk of mood and anxiety disorders, mainly major depression (threefold risk) and phobia (

Table 2). The phobias were primarily specific phobias (74% in the high-risk group and 89% in the low-risk group). Many had more than one type of phobia. None of the other offspring disorders differed significantly by risk group. Rates of drug dependence (p=0.09) and any disorder (p=0.06) being higher in the high-risk group fell short of statistical significance. These lifetime disorder rates were cumulated across interviews and best-estimate procedures conducted over many years, during which the same impairment criteria were not always included in standard DSM criteria. Therefore, these rates might include disorders that are milder and less impairing. To account for this possibility, we used mean GAS scores across all waves to identify subjects with impairing disorders. Tables S1, S2, and S3 in the

data supplement accompanying the online version of this article show the disorder rates by risk group after applying GAS score cutoffs of 70, 75, and 80. Applying impairment criteria reduces the rates of disorder, but the relative risks remain similar regardless of impairment (<75 or <80), about threefold for major depression and anxiety. The number of low-risk offspring with GAS scores <70 (i.e., highly impairing disorder) was too small to allow meaningful analysis. Nonetheless, using GAS scores <70, the relative risk for mood disorders was over 10-fold in the high- versus low-risk group (p=0.03). Absolute rates of disorder cannot be obtained from a case-control study. It is the relative rates between groups that are important. The relative risks of disorders between high- and low-risk offspring were similar regardless of impairment criteria.

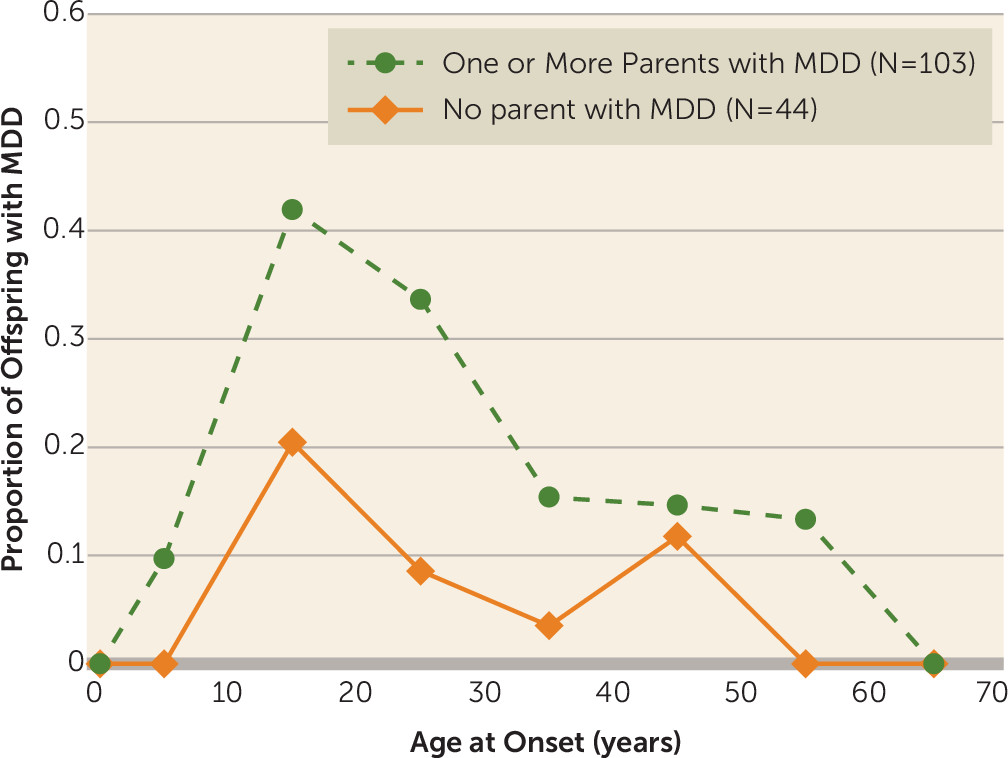

Figure 1 shows that even with a 30-year follow-up, the peak incidence for major depression remains late adolescence (mean age=19.5 years [SD=10.2]), with similar patterns of onset in the high- and low-risk groups and a threefold increased rate in the high-risk group, as found in the 20-year follow-up. Prepubertal onset major depression (before age 13) was uncommon. Whereas the cumulative risk of major depression for high-risk offspring was nearly triple that of the low-risk group, the relative risk of prepubertal onset major depression was 10-fold (relative risk=10.7, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.5–76.4). The longer follow-up shows a small increase in onsets of major depression at around 45 years in the offspring of low-risk parents, all in women. Due to the small numbers, we did not test for significance.

Since our lifetime rates of major depression by risk group are strongly affected by the early onset, we compared risk groups on depression onsets between ages 20 and 40 and between ages 40 and 60. In each analysis, we excluded offspring who had already had an onset of depression before the age range being examined. Figure S1 in the online data supplement shows that the failure curves were significantly different (log-rank chi-square=9.49, df=1, p=0.002), with the high-risk group showing significantly greater risk for first depression at ages 20–40 compared with the low-risk group. However, starting at age 40 and ending at age 60, and including in the analysis offspring who did not have a depression episode prior to age 40, the failure curves for the two risk groups were not significantly different (see Figure S2 in the data supplement).

We also did a check on recurrence risk in offspring with early-onset (<20 years old) major depression by risk group. We found that high-risk offspring with early-onset major depression had an increased risk of recurrence after age 20 (p=0.0013), whereas the low-risk offspring did not. These findings, while based on a small sample, suggest that most of the familial risk of major depression was based on the early-onset cases and that recurrence risk among high-risk offspring was also significantly increased.

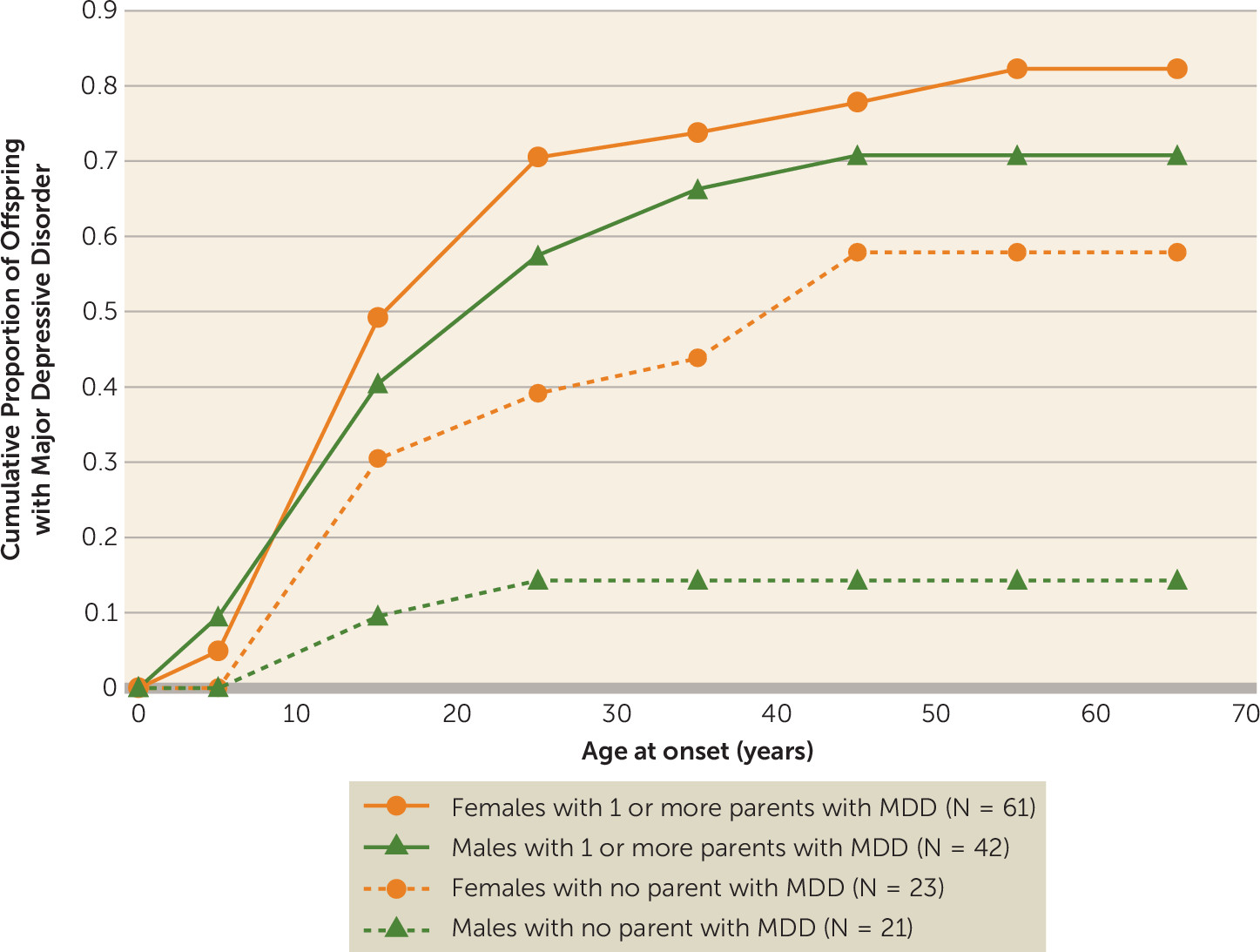

Figure 2 shows the cumulative rates of major depression by age at onset by gender. The rates of major depression are overall higher in women than men. However, among high-risk offspring, there are no statistically significant differences in cumulative rates of depression over time by gender (F=0.88, df=1, 54, p=0.35). Conversely, among low-risk offspring, the cumulative rates of depression were significantly higher in females compared with males, with a greater than fourfold increase in cumulative rates among women by age 65 (relative risk=4.89, 95% CI=1.33–17.94).

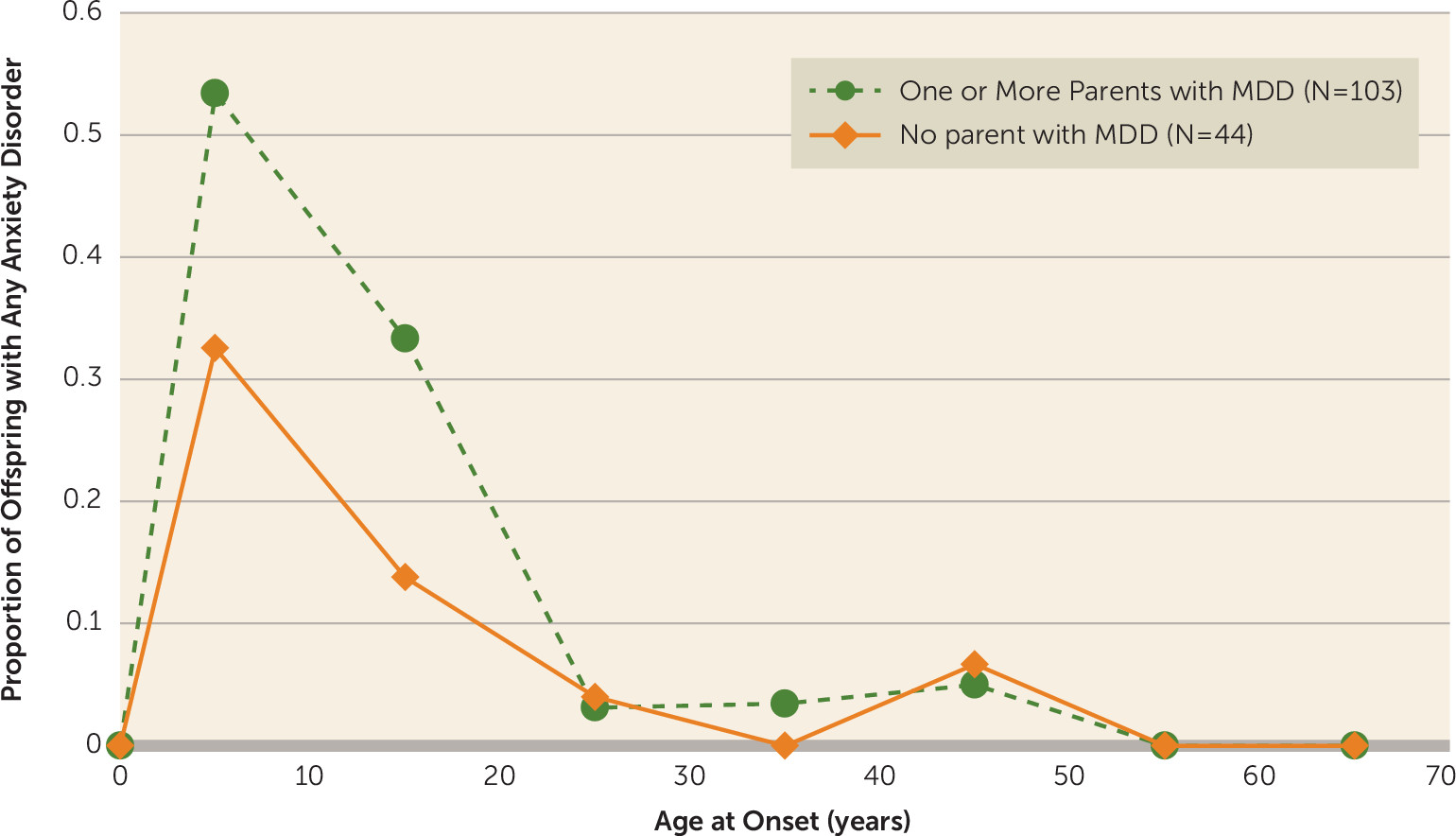

The earlier age at onset pattern for anxiety disorders compared with that for major depression is shown in

Figure 3. As we found at the 20-year follow-up, the peak incidence of anxiety disorders (phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder) was before puberty or in early adolescence and much earlier than for major depression, especially in the offspring of depressed parents. There is no evidence of increased first onsets later. Phobias had the earliest onset, and panic disorder had onset in early adulthood.

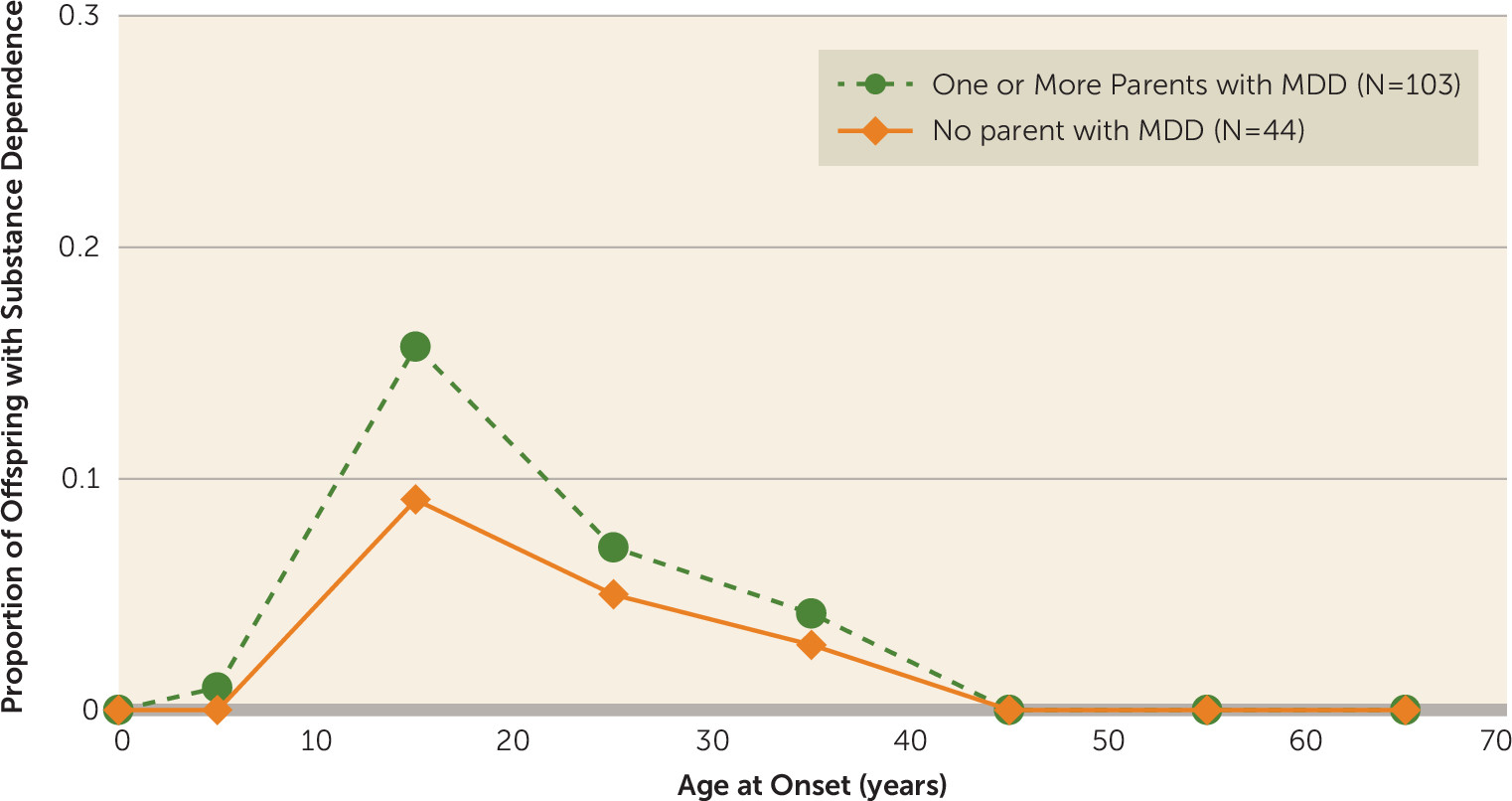

As shown in

Figure 4, the peak onset for substance dependence was also in adolescence or young adulthood, higher in the high-risk offspring at that period and largely in males.

Impairment and Treatment

By the 30-year follow-up, offspring of depressed parents were more likely to be separated or divorced and significantly more likely to have fewer children (

Table 3). They also received significantly more and longer treatment for emotional problems, more continuous treatment, and more medication for emotional problems and overall were functioning more poorly (p=0.0003). The offspring by risk group did not differ by education, employment status, or income. We also compared the impairment scores (GAS) of the depressed offspring by risk group. The finding of depressed offspring of depressed parents having worse overall functioning (mean=76.1 [SD=9.2], N=76) than depressed offspring of nondepressed parents (mean=79.6 [SD=7.2], N=15) (Z=−1.75, p=0.08) nearly reached statistical significance.

Medical Conditions and Mortality

At the 20-year follow-up, we saw significantly more medical conditions in the high-risk offspring, particularly cardiovascular and neuromuscular disorders. At the 30-year follow-up, there are no differences between risk groups (see Table S4 in the online data supplement). This is likely due to the low-risk group developing more illnesses as they are now in middle age.

Mortality rates are based on the full cohort of offspring who participated in wave 1 or 2 (N=261). The overall mortality rates were 5.5% (10 of 181) in the high-risk offspring and 2.5% (2 of 80) in the low-risk offspring. Deaths from natural causes were similar in both offspring groups (2.8% compared with 2.5%). However, the difference in mortality between high- and low-risk offspring was in death from unnatural causes, in which 2.8% of the high-risk offspring and none of the low-risk offspring died from unnatural causes (suicide, N=2; car accident, N=1; overdose, N=2). Four of these five deaths were in males; one death occurred at age 16, and the others at ages 30, 39, 42, and 42, respectively. The mean age at death from all causes was 38.8 years (SD=10.2) in the high-risk offspring and 46.5 years (SD=4.9) in the low-risk offspring, which approached statistical significance (Z=1.87, p=0.06). Although the differences in offspring mortality rates are notable, the statistical tests were not significant, likely because death overall was relatively rare and left the tests underpowered. For instance, the test comparing the rates of 5.5% compared with 2.5% had an observed power of only 0.124. This corresponds to a type II error rate of 0.876 (i.e., 1 – power), or an 87% probability of failing to reject an incorrect null hypothesis of no mortality difference between the high- and low-risk offspring populations from which our samples derive.

Discussion

The 30-year follow-up extends what was found at 20 years: the increased risk, over threefold, of major depression and anxiety disorder in the biological offspring of depressed compared with nondepressed parents; the onset of major depression in adolescence and early adulthood regardless of risk; a low prevalence but large increase (10-fold) in prepubertal onset major depression in the high-risk offspring; the onset of anxiety disorders before puberty or in early adolescence; and the increase in substance dependence in adolescence and young adulthood in the high-risk offspring.

The ages at onset of major depression, anxiety disorders, and substance dependence were consistent in both risk groups and with age at onset patterns in the general population (

30). There are no new peak onset years in the high-risk group. The slight increase in first-onset major depression in low-risk women around age 45 may represent perimenopausal major depression, as described recently (

31,

32).

The follow-up also shows increased morbidity and mental health treatment in the high-risk offspring, more divorces, fewer children, and overall poorer functioning. Decreased fertility in depressed patients, especially men, has been shown in recent studies from Sweden involving 2.3 million individuals between 1950 and 1970 (

33). We did not find a gender difference in fecundity. Both men and women in the high- compared with low-risk group, whether or not they had major depression, had fewer children.

The increased risk of cardiovascular and neuromuscular diseases in the high-risk offspring seen at 20 years had disappeared, likely because the low-risk group of offspring has begun to “catch up.” Medical problems have increased in both groups as they have aged.

Our high-risk offspring, who were mainly white and in midlife, had an early age of death from unnatural causes, mostly among males. Similarly, a rising mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic men, largely accounted for by deaths from suicide and substance abuse, has been reported (

34). A separate meta-analysis of mortality in subjects with mental disorders found that 17.5% of deaths were due to unnatural causes, with a median of 10 years of potential life lost (

35).

Our study has several limitations. The sample size did not allow detailed comparisons by gender, specific disorders, or a host of environmental factors. The sample was underpowered to reach significance levels for mortality. There was only one comparison group, and the probands were selected from a treatment clinic, had moderate to severe depression, and were all white. While there were six waves of interviews over 30 years, more closely spaced assessments may have given better descriptions of risk, recurrence, or treatment.

Our study identifies a population at very high, long-term risk, the biological offspring of a depressed parent. Clinically, the findings show the possibility of preventing disability by targeting, in early adolescence, offspring of depressed parents who develop symptoms of depression. While both high- and low-risk offspring have their peak onsets of major depression in their youth, it is the high-risk offspring who have the recurrences and poor long-term course. The findings show the potential of a family history assessment. In the era of precision medicine, this simple clinical tool, family history, for targeting a high-risk population (the depressed offspring and parent) should not be overlooked. The variance explained by the human genome for common human diseases is often not susceptible to direct clinical or public health action (

36). Simple clinical tools and interventions may be useful until a more biologically based understanding can be found. We, as well as others, have also shown the potential impact on the offspring of treating the depressed parent to remission, whether by medication (

37–

39) or psychotherapy (

40). Even a highly efficacious prevention program for previously depressed adolescents was less effective if the parent was depressed (

41). We do not know the long-term implications for the offspring into middle age, but in the short-term, successful treatment of a depressed parent may reduce morbidity in the offspring at a vulnerable age.