There is overwhelming evidence that disasters result in increased rates of mental health problems, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression (

1,

2). Although much evidence indicates that this impact is moderated by social support (

3–

5), the exact role of social relationships and psychosocial resources in protecting against mental health deficits has been the subject of debate. Although diminished social participation has been reported as a risk factor for poor mental health after disaster (

6,

7), there is also evidence that PTSD hinders subsequent positive social support and causes withdrawal from social connections (

8,

9). It has also been shown that disaster can alter the perceived availability of social structures (

10). Despite these findings, the specific nature of how people interact in networks after disaster and how different patterns of connectedness affect mental health have yet to be articulated.

A major reason for our limited understanding of the role of societal factors in postdisaster mental health has been the focus to date on individual responses at the expense of understanding relationships

between individuals and societal subgroups. Specifically, postdisaster studies that take into account social factors have typically measured individuals’ perceptions of social support relationships (

6–

9). This approach can be contrasted with the sociocentric framework of social network approaches (

11,

12). Social networks can be regarded as a web of one-to-one links or ties that exist among individuals (or groups or organizations). This approach allows researchers to map the extent to which the social structure of person-to-person relationships is related to health and other outcomes. In turn, through various methods referred to generally as social network analysis, it is possible to analyze the co-occurrence of health outcomes in a sociospatial sense, as well as how these outcomes may relate to specific ideas of structural position within a network (

13). Network research methods can show how a particular outcome may depend not only on the number of one’s immediate social relationships, but also on 1) the particular outcomes observed concurrently in others to whom one is linked either directly or indirectly, and 2) on larger substructures of network ties involving multiple individuals. Increasingly, work in this area has shown that where one is positioned within a social network, and the connectedness of that social network, moderates many general health outcomes, including obesity (

14–

16), tobacco use (

17,

18), and alcohol consumption (

19). Moreover, the nature of one’s social networks has been shown to have an impact on a range of psychological functions, including depression (

20–

23), happiness and positive mood (

24,

25), and loneliness (

26). Together, these methods open the door to consideration of social selection and social influence mechanisms in the prevalence of mental health conditions, and of how these outcomes may spread over social ties or influence whom people choose to associate with (

21). Furthermore, in addition to mapping one-to-one ties between pairs of individuals, social network analysis allows for the identification of many types of network structures, such as when a person is an intermediary between others who are not interconnected themselves (

20). An example of this approach is that in the context of social isolation, women having friends who are not friends with each other is predictive of suicidal ideation (

27). This situation may be contrasted with scenarios in which a person is part of an integrated network in which the people they know also know each other.

However, despite the increasing popularity of networks as a general conceptual tool and its increasingly sophisticated use in health research generally, exceedingly few studies have employed social network research methods to investigate social determinants of postdisaster mental health (

28–

30). Moreover, these studies have relied exclusively on personal (egocentric) network methods, in which each participant is surveyed about his or her direct social relationships (as he or she perceives them), rather than placing individuals within a larger community network structure of direct and indirect ties (a sociocentric, or whole-network, approach). This dearth of network investigations of postdisaster mental health is unfortunate because one distinguishing feature of most disasters is their collective nature, with many disasters (e.g., hurricanes, earthquakes) having an impact on a community of individuals who are known to each other (

31). Such disasters therefore not only traumatize individuals, they also cause widespread community and infrastructure disruption, instigating social upheaval and the relocation of affected individuals away from the community (

32). A pivotal role is therefore afforded to social factors in postdisaster recovery (

33). Accordingly, the goal of the present study was to apply social network methodology to examine 1) how the presence and configuration of social ties between survivors of a large disaster are associated with mental health outcomes, and 2) how mental health outcomes may occur within connected social networks. We predicted that mental health conditions (PTSD and depression) would be inversely related to close social ties, defined in three different ways: close ties to others as nominated by the participant (termed the

ego), close ties to the participant as nominated by other participants (termed

alters), and mutual (reciprocal) ties as nominated by a pair of participants. Next, given previous evidence that depression can spread within a social network (

20), we expected that people with depression and PTSD would be disproportionately linked to one another within the network. Furthermore, we explored the possible influence of more complex network patterns involving multiple ties in various configurations. Finally, we considered the impact that disaster-related experiences within one’s immediate social network have on one’s own mental health.

Method

Participants

In February 2009, Australia suffered one of its most devastating disasters as severe bushfires affected most of the state of Victoria, with the worst occurring on Saturday, February 7. Commonly referred to as the “Black Saturday” fires, this disaster resulted in 173 fatalities and 3,500 buildings damaged or destroyed, and it had a massive adverse impact on community infrastructures (

34).

The “Beyond Bushfires: Community, Resilience, and Recovery” study (

35) included adults (at least 18 years of age) living in 25 communities in 10 rural locations that were selected because they were variably affected by the fires. The 2006 census data indicated a total adult population of 7,693 in the selected communities. The Victorian Electoral Commission provided contact details for both current residents and those who had relocated since the fires (N=7,467 adults), and a letter was sent to them inviting them to participate in the study, with a postage-paid reply envelope. In total, 14.1% of eligible individuals completed the interview (N=1,056). (Local requirements dictated that potential participants could not be telephoned until they had contacted the research team by mail to indicate their willingness to participate.) Relative to available census data, the sample who participated in this study were, on average, older and more educated than the general community, and more likely to be female (

35).

Measures

Network name generator.

Respondents were initially asked to nominate the persons to whom they felt “particularly close.” Participants were then asked to provide a full name, age, gender, address, and role relationship to that person (various family relations, friend, workmate, neighbor, etc.). It was on this basis that record matching was performed. These ties pertain to those that are the most intimate and frequent, likely serving as a source of emotional support and normative sanctioning.

PTSD.

Probable PTSD was assessed using an abbreviated version of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist–Civilian Version (

36) comprising four items, each scored on a 5-point severity scale, that index key symptoms of PTSD and refer to the previous 4 weeks. Adopting a cutoff score of 7 on the abbreviated version achieves an efficient estimation of PTSD diagnosis relative to the full version of the instrument (Cronbach’s alpha=0.85) (

36).

Depression.

Depression was assessed using the depression module of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (

37). To determine presence of some mood disturbance, we used a score of 5 as the cutoff to determine presence of depression (Cronbach’s alpha=0.85) (

37).

Disaster exposure.

A composite measure of severity of bushfire exposure was assessed in terms of fear for life (yes/no), death of loved ones (yes/no), property loss (ranging from 0=nothing to 10=everything, recoded into approximate quartiles [0, 1–4, 5–9, 10]).

Subsequent life events.

Major life events occurring since the bushfires were assessed, including an index of nontraumatic stressors (negative changes in employment, loss of income, livelihood) and traumatic stressors (assault/violence, serious accident). Relocation away from community after the fires was indicated by comparing past and current residential addresses (

38).

Procedure

The study was approved by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee. Data collection occurred between December 2011 and January 2013. The interview was conducted in a combination of telephone and web-based formats. After the participant provided informed consent, the interviewer initially asked a broad array of sociodemographic questions, then asked questions about social connections, events that have occurred since the fires, and events that occurred on the day of the Black Saturday fires, and then administered the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist–Civilian Version and the PHQ-9. Additional questions relating to physical health, mental health, resilience, and connection to community were asked but are not included in the analyses reported here.

Network Data and Data Analysis

Social network data were constructed by means of an extensive record-matching process in which personal information (name, address, gender, and age) of participants and their social network nominations were linked. Furthermore, the network data were directed, with individuals represented as sending ties to and receiving from others. This lends an additional level of precision in the interpretation of data, as emotional closeness can be ascribed to the feelings of one individual toward another. This approach is a major improvement on previous (egocentric) studies that have only asked about the numbers of other people a participant is connected to, along with a few demographic characteristics, without key information on the concurrent mental health outcomes and disaster experiences of those people.

Several criteria determined inclusion in the final network sample: participants nominated someone else in the network; were nominated by someone in the network; or did not name any close ties, without declining to participate (referred to as “isolates”). Excluded were participants who both declined to name close ties and were not nominated by other participants, as well as those whose network ties were not participants in the study (N=413). An additional set of participants (N=85) was included in the analysis in a strictly exogenous (predictive) fashion, with their network ties and mental health outcomes only serving as predictors for other individuals: these individuals had declined to nominate their own network contacts (N=34), and/or had missing data on individual-level attributes (N=31), or had moved into a study community since the bushfires (N=20). One participant had a missing value for presence or absence of probable PTSD, which was imputed from other data. The final sample for analyses comprised 558 individuals.

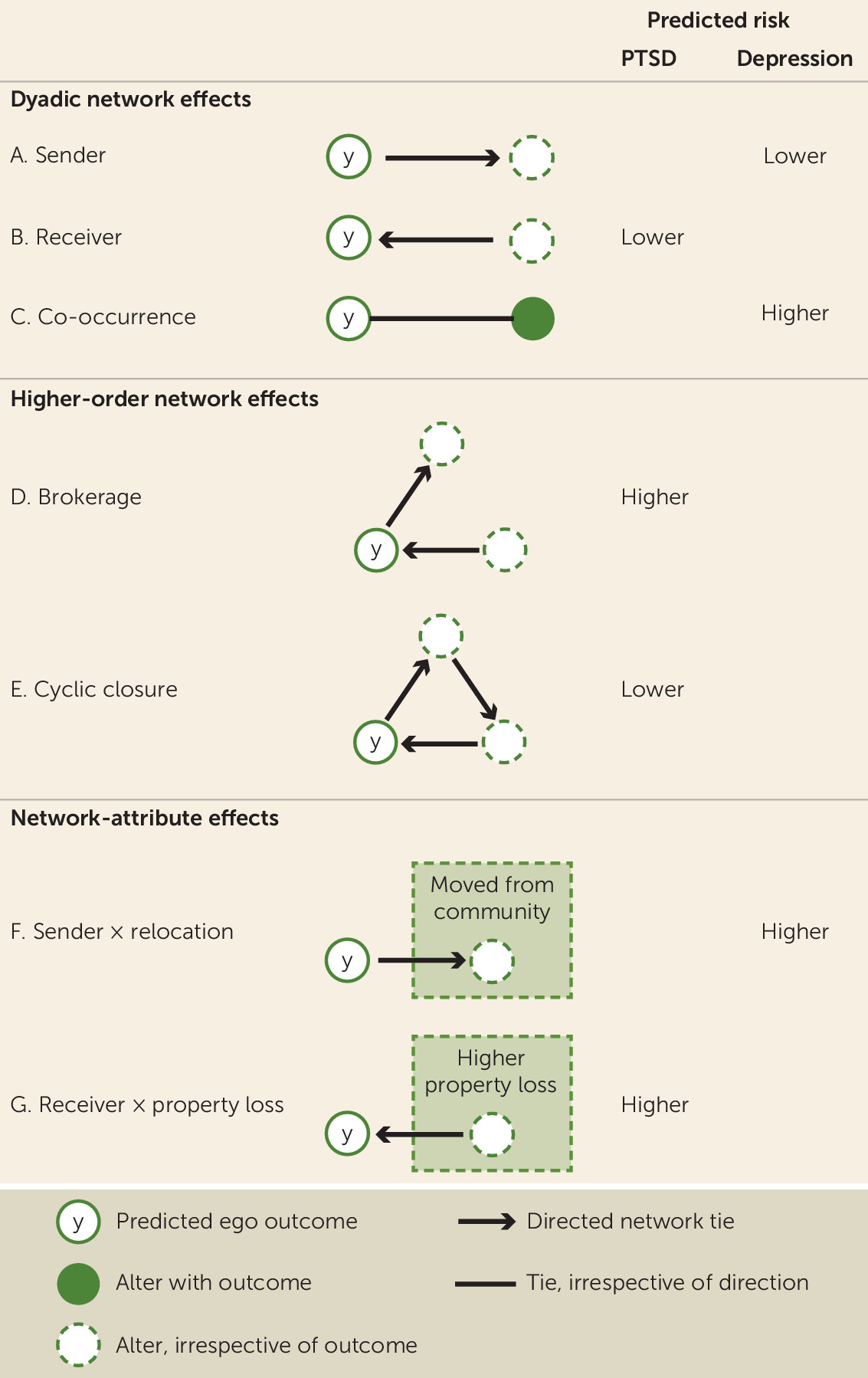

The class of network statistical model used here is an

autologistic actor attribute model (ALAAM) approach (

39–

41). ALAAMs allow examination of how individual behavior, attitudes, or other outcomes may be constrained and enabled by the structure of surrounding social network relationships. As in a conventional logistic regression, an ALAAM may include a range of individual-level factors (e.g., disaster experiences, sociodemographic characteristics) to predict a dichotomous outcome at the level of the individual. However, unlike conventional regression methods, which carry an assumption of independence of observations, ALAAMs take interdependence into account. Through the use of Monte Carlo Markov chain maximum likelihood estimation, ALAAMs can test a principled set of assumptions (referred to as conditional dependence assumptions) that detail how various configurations of network ties affect the individual outcome (

41). As social ties are by definition interdependent, the use of ALAAMs aligns the data with the method of analysis and is therefore a much more theoretically precise approach to studying social networks. In particular, the sociocentric (whole-network) approach to network analysis, on which the ALAAM is based, allows us to examine several network effects of particular interest that are not possible with conventional statistical methods. First, it permits us to examine how one’s network partner’s outcome affects one’s own outcome. A positive co-occurrence effect indicates a higher likelihood of having a given outcome if one has a network partner who also has that outcome; this suggests social processes of contagion or social selection. Second, it allows us to consider the impact of incoming network ties, and thus the importance of how others feel toward the focal individual. Third, a sociocentric approach allows us to consider the association between an outcome and network ties that the focal individual is not directly involved in. For instance, an individual’s mental health may depend in part on the degree to which his or her network partners know one another, communicate with one another, and can influence one another. In this respect, a network position of particular interest is that of brokerage, or the position of being connected to two (or more) individuals who have no direct ties between them.

For both depression and PTSD, we conducted a conventional binary logistic regression containing individual factors (personal attributes and events) to serve as a counterpoint to the more principled network ALAAMs. Next, for each outcome, we estimated an ALAAM. All dyadic network effects were specified to focus on the impact of outgoing ties, incoming ties, reciprocal ties, and the co-occurrence of either outcome (depression, PTSD) across these ties. Furthermore, more complex network configurations involving three or more individuals were specified through a backward elimination procedure. While backward elimination carries the risk of potentially overfitting the data, the general lack of a comprehensive theoretical framework of networks and mental health necessitates a partially exploratory approach. We therefore started with a full complement of network configurations (i.e., activity/popularity effects, brokerage effects, and triangular closure) and removed more complex (nonsignificant) network effects. We then calculated simpler network configurations, re-estimating the model at each step (the initial full models can be seen in Tables S1 and S2 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article). Furthermore, the models each included a set of “alter” effects, which address how being connected to other individuals who have certain attributes or experiences (i.e., other people leaving the community, other people’s property damage) may additionally influence ego’s mental health outcomes.

ALAAMs were estimated using the MPNet software program (

42). Each ALAAM model was assessed by means of a goodness-of-fit test; this is a stringent test of the data to ensure that the estimated model can reproduce both within-model and out-of-model effects reliably. By convention, significance testing is analogous to a Wald test, with a value of 2 considered to be significant (and analogous to a parametric test statistic of 1.96).

Discussion

Although commentators have often emphasized the role of social support on postdisaster mental health (

6,

43,

44), the patterns by which mental health occurs across social networks has not been explored in a postdisaster context. This study represents one of the first applications of social network analysis to the study of postdisaster mental health outcomes, and the first use of complex statistical models for social networks in the field. The sociocentric approach, in combination with the use of ALAAM, allows analyses to extend beyond an individual’s own perception of his/her own social ties to provide a more integrated investigation of how social networks intersect with mental health outcomes following disaster.

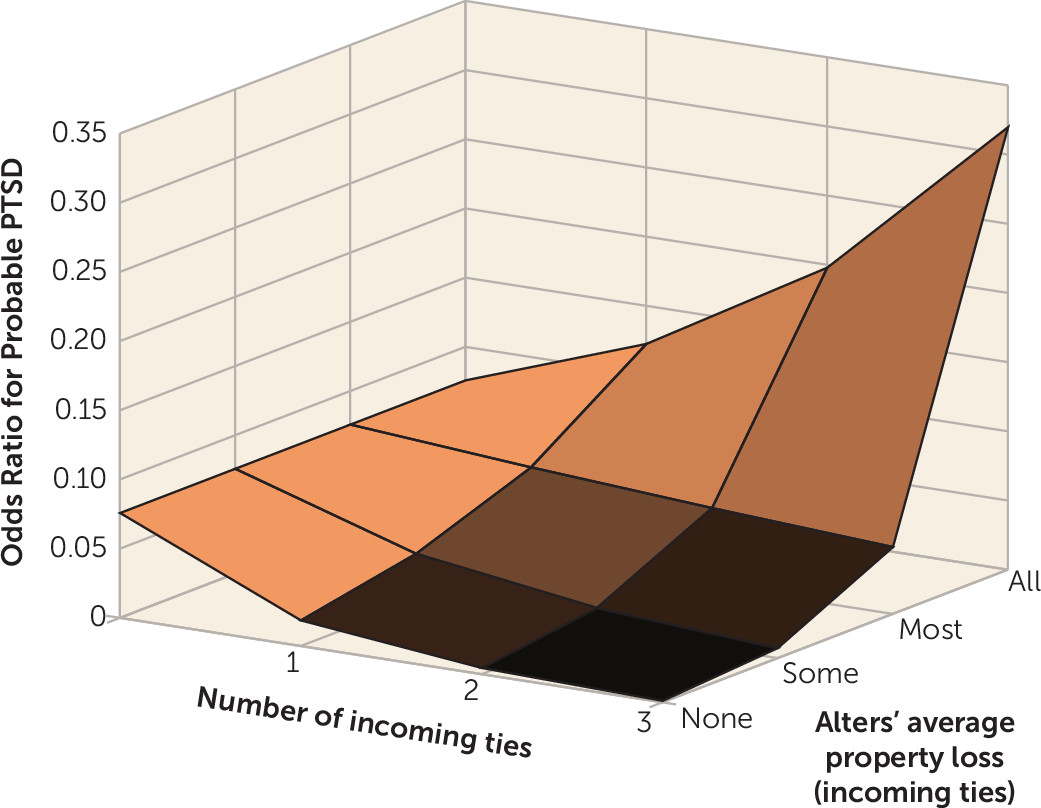

The novel finding in this study is that after the disaster, the less others (alters) nominated a focal individual (ego) as someone they were close to, the greater the likelihood of the focal individual (ego) suffering PTSD. The exception to this pattern was if the nominating tie came from individuals with higher property loss: the more that ego (the focal individual) was nominated by alters (other participants) who had higher property loss, the higher ego’s associated risk of PTSD. Put another way, as one’s own property loss increased, so did the risk of PTSD for one’s close social contacts, even after controlling for their own property loss. It appears that whereas participants’ depressive symptoms were increased if they reported less connectedness to others, reduced close ties

from others was specifically associated with PTSD. The finding that PTSD was specifically associated with fewer ties from other people may be explained by the well-documented pattern for people with PTSD to become socially detached and nonresponsive to their environments (

45–

47). It is possible that people with more severe PTSD reactions retreated from social connections with others, thereby isolating them from otherwise available networks. The interpretation is further supported by the finding that receiving a tie from an alter with higher property loss was associated with a higher probability of having PTSD, suggesting that contact with others who have experienced their own trauma and social disruption may compound PTSD symptoms in the individual. Over the long term, this may prompt the affected individual to withdraw from social interactions with that person, thereby enacting the avoidance component of PTSD and leading to a weakening or dissolution of the relationship. Alternatively, it is feasible that diminished receipt of social connectedness directly led to greater PTSD because it deprived these disaster survivors of social support. It is also possible that these two processes are mutually reinforcing.

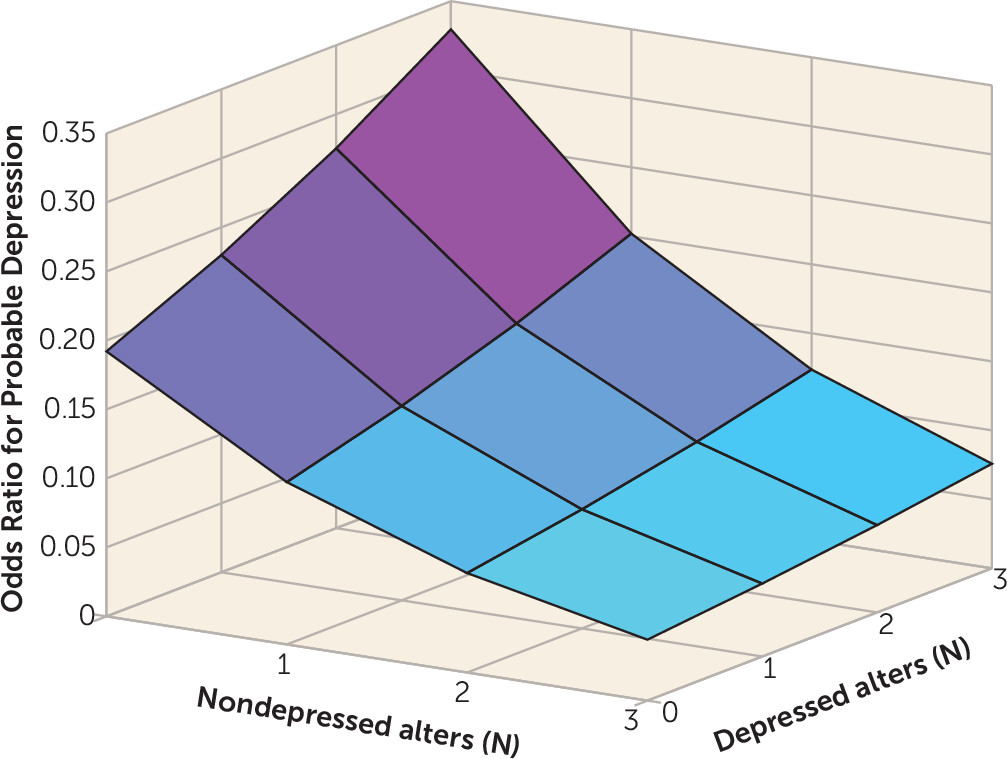

The other core finding from this study related to depression. We found that participants who reported fewer ties with others were at greater risk for probable depression. This is hardly a surprising finding given that this self-report is largely consistent with the methodology of previous studies that have relied on self-reported social support in demonstrating its relationship with mental health. The novel finding with respect to the postdisaster literature was that people who were depressed were socially connected with others who were also depressed. Several explanations may account for this observation. It is possible that one’s depression increased the more one had connections with other depressed people because of an influence effect of the depressed state. That is, being depressed may affect the mental state of people one interacts with because one’s mood can directly affect other people’s mood states. This interpretation accords with a previous study of a general population that depression can spread along social networks (

20). However, drawing this inference would require longitudinal data, so other possibilities need to be considered. It is possible that depressed people were socially connected because they were drawn to each other. Alternatively, common exposures to environmental factors may link people who are depressed; for example, factors associated with their social structure, community, or experience of the disaster that link people to each other may independently contribute to depression. In this context, we note that previous research outside the disaster context has suggested that depression may co-occur within a network as a function of withdrawal from other social networks, which in turn results in depressed individuals being more connected with each other because of their limited social networks (

21).

Interestingly, the pattern of depressed people being linked to each other was not one seen for PTSD. PTSD is a condition primarily driven by anxiety maintained by distressing memories of a triggering traumatic experience (

48,

49), and accordingly it is predominantly driven by internal experiences. It could be argued that the maintaining factors of PTSD are internally generated and are rooted in a personally threatening experience; the capacity for PTSD to spread along social connections is less than that for depression because PTSD is more susceptible to the effects of the traumatic experience than to ongoing mood effects. Furthermore, since PTSD is often characterized by social withdrawal (

50), it may be less likely that the effects of PTSD will be communicated to others because people with PTSD are prone to avoiding social interactions; this interpretation is supported by the finding that PTSD severity is associated with fewer connections with other people.

Another finding was that although people who left their community were at no greater risk of depression, for those remaining in the affected community, feeling close to those who had left predicted depression. This accords with evidence that separation from a close other increases risk for depression (

51). Moreover, a delay in connecting with social supports has been shown to be associated with an increase in risk for mental problems following a mass disaster (

52). It is possible that feeling close to another who is not proximally available enhances depression risk because of a sense of loneliness.

Another key observation was that PTSD was associated with “brokerage” patterns, indicating that PTSD was more likely when people had both incoming and outgoing social ties, indicating an in-between social position. Crucially, this effect was countered when the brokerage pattern was part of a cyclic pattern. This finding accords with previous patterns of impaired mental health being linked to fractured social networks with competing role demands coming from unconnected portions of their social network (

27). By contrast, cyclic network structures are sites of generalized social exchange, affording equal status, cohesiveness and solidarity, and robust norms of reciprocity among several people (

53). It is possible that by virtue of their interconnections, these individuals are likely better situated to coordinate support for one another, leading to a reduced risk of PTSD. An alternative interpretation is that brokerage structures may be more likely for PTSD-affected individuals as a result of their avoidance strategies. Brokerage positions imply that the person is part of two different social settings that are relatively private with respect to one another. The affected individual may withdraw to one setting when confronted with upsetting stimuli or interactions within the other. Accordingly, if the unified setting implied by the triadic configuration is marked by reminders of the trauma, the PTSD-affected individual may ultimately withdraw.

We recognize several methodological limitations. First, these conclusions are based on cross-sectional data, and longitudinal social network analysis is needed to more confidently map the causal directions of social effects. Second, it is possible that unmeasured characteristics influenced how disaster survivors were linked to each other and how mental health status may co-occur between individuals. Third, we assessed probable PTSD and depression rather than full diagnostic caseness. Fourth, as would be expected in a community study of this nature, there are missing data. For this new class of network model, the extent to which missingness might affect statistical power is not yet fully known; nor is the effect of extensive missing network data on the precision of parameter estimates.

The overall response of the sample was only 16% of potential participants. Although this is a low response rate relative to studies that engage in random sampling in population studies, it is consistent with studies that are ethically required to adopt an opt-in approach that involves consent prior to researchers contacting participants; for example, one previous population study employing this approach (

54) achieved a 20% response rate, and among participants who were sociodemographically comparable to the population reported here, the rate was 16%, the same rate achieved in the present study. This pattern accords with much evidence of lower response rates for studies requiring that participants contact the research team to provide consent to interview them (

55–

57). Reviews of response rates across jurisdictions requiring initial consent have robustly demonstrated markedly lower rates than in regions that do not have this requirement (

58). This issue can complicate the representative nature of the data because nonresponse at the initial consent phase can be moderated by age, gender, and sociodemographic factors (

54). We qualify these cautions with the recognition that network analyses are less susceptible to the effects of bias than conventional epidemiological studies because they examine the social interdependence of the sample, and hence the independence assumptions of traditional population studies are not adopted (

59). Nonetheless, biases may influence results, so we replicated our major findings by limiting the sample to participants who were age- and gender-matched with community census data (for a full discussion, see the

online data supplement). The present findings warrant replication with samples that can achieve larger response rates to limit the possibility of biases affecting results.

In conclusion, this study provides important new evidence concerning postdisaster social structures and how they are associated with mental health outcomes. Depression appears to occur in people who are connected, which may point to the importance of social interactions in maintaining depressive responses. Moreover, PTSD was associated with more fractured social networks. Taken together, these findings highlight the need to look beyond individual effects if posttraumatic mental health is to be adequately understood. Delineating social structures after disaster and how these moderate mental health trajectories can shed light on social interventions that may facilitate adjustment after disaster.