Trichotillomania is an often debilitating psychiatric condition characterized by recurrent pulling out of one’s own hair, leading to hair loss and marked functional impairment (

1,

2). Although discussed in the medical literature for over a century (

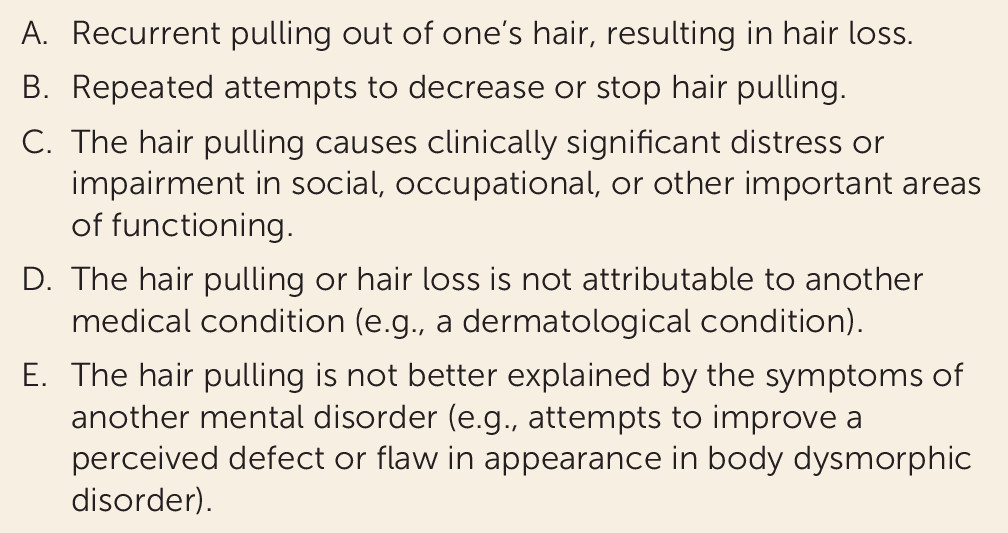

3), trichotillomania was not officially included as a mental disorder in DSM until 1987, when it was classified as an impulse control disorder not elsewhere classified in DSM-III-R. In DSM-5, trichotillomania was included in the chapter on obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, along with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), excoriation disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, and hoarding disorder. The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for trichotillomania are listed in

Figure 1.

Epidemiology

Nationwide epidemiological studies of trichotillomania are lacking, but the prevalence of the disorder has been explored in smaller studies, mostly in college settings. In the United States, individual studies based on questionnaires administered to college students have estimated the lifetime prevalence of trichotillomania to be around 0.6% (

1) and the point prevalence in the range of 0.0%−3.9% (

4,

5). The sample sizes of these studies ranged from 200 to some 2,500 participants. A study that examined 832 people who were visiting U.S. retail stores in a college city identified trichotillomania in five individuals (0.6%) (

6). There have been a handful of studies in non-U.S. settings. King and colleagues (

7) explored hair pulling using questionnaires and interviews in 794 Israeli 17-year-olds during a preinduction assessment for military service. The lifetime prevalence of hair pulling was estimated at 1%, but none of the subjects met DSM-III-R criteria for trichotillomania. In a cross-sectional study conducted in 210 students at medical colleges in Karachi, Pakistan, probable trichotillomania (measured using a “habit” questionnaire) was evident in 13.3% of the sample (

8). Collectively, prevalence estimates appear higher when using more recently formulated DSM criteria, which are less strict. It should be borne in mind too that people with trichotillomania are often ashamed of and embarrassed about their condition, so these data may constitute underestimates of the true population prevalence.

In adults, trichotillomania appears to have a large female preponderance, with a female-to-male ratio of 4:1, which is uniquely high among psychiatric disorders. In childhood, the sex distribution has been found to be equal (

7,

9). Studies further demonstrate that as a behavior, hair pulling appears to be quite common and often presents along a continuum from mild to severe. When hair pulling meets criteria for trichotillomania, as in the case vignette, interventions should be considered.

Clinical Description

The typical age at onset of trichotillomania, usually 10–13 years, is remarkably consistent across studies (

10–

12). This characteristic age at onset appears to be consistent across different cultural settings (

2,

13).

In trichotillomania, pulling can be undertaken at any bodily region with hair, but the scalp is the most common site (72.8%) followed by the eyebrows (56.4%) and the pubic region (50.7%) (

2). Triggers to pull may be sensory (e.g., hair thickness, length, and location and physical sensations on scalp), emotional (e.g., feeling anxious, bored, tense, or angry), and cognitive (e.g., thoughts about hair and appearance, rigid thinking, and cognitive errors) (

10). In our experience, most individuals report a variety of triggers, and which triggers are primary may change even within the same day. Many patients report not being fully aware of their pulling behaviors, at least some of the time—a phenomenon known as “automatic” pulling; “focused” pulling, in contrast, generally occurs when the patient sees or feels that a hair is “not right,” or that a hair feels coarse, irregular, or “out of place” (

14).

Psychosocial dysfunction, low self-esteem, and social anxiety are all associated with trichotillomania, largely as a result of an inability to stop pulling and the resulting alopecia (

9,

15). Individuals frequently report failure to pursue job advancement or avoidance of a job interview because of the pulling (

2). Many avoid intimacy for fear that their partner may play with their hair and possibly expose areas of alopecia. Most individuals avoid swimming, for fear that it will draw attention to their alopecia. Nearly one-third of adults with trichotillomania report a low or very low quality of life (

16).

Trichotillomania may result in unwanted medical consequences. Pulling of hair can lead to skin damage if sharp instruments, such as tweezers or scissors, are used. Over 20% of patients eat hair after pulling it out (trichophagia), a behavior they feel is even more embarrassing than the pulling. In fact, many people with trichotillomania do not divulge this fact until they feel greater trust in the clinician. The ingestion of hair can result in the formation of gastrointestinal hairballs (trichobezoars), which can cause obstructions that may require surgical intervention (

17).

Screening for Trichotillomania

Because hair pulling represents a relatively specific type of behavior, identification of trichotillomania is relatively straightforward, provided the clinician screens for it and provided that the patient is willing to divulge the symptoms. Although the course of illness may vary, when untreated, trichotillomania is commonly a chronic disorder with fluctuations in intensity over time (

1). Two studies of adults with trichotillomania found a mean illness duration of 21.9 years (

17,

18). Individuals report that the symptoms of their pulling, although waxing and waning in intensity over time, frequently persist without treatment.

Seeking help from a mental health clinician is uncommon among individuals with trichotillomania. In fact, one study found that of 1,048 individuals who met criteria for the disorder, only 39.5% had sought treatment from a therapist and only 27.3% had sought treatment from a psychiatrist (

2). One reason for this low rate of treatment seeking seems to be that the vast majority of individuals with trichotillomania (87%) feel that providers know little about the disorder. Other reasons for not seeking treatment can include feelings of shame and embarrassment, lack of awareness that hair pulling constitutes a recognized psychiatric condition, and fear of clinicians’ reactions (

2).

Trichotillomania occurs with a variety of other disorders, such as major depressive disorder (39%−65%), anxiety disorders (27%−32%), and substance use disorders (15%−19%) (

14,

19,

20). Where data regarding age at onset are available, trichotillomania generally predates these co-occurring disorders (

21). A study of 894 individuals with trichotillomania found that 6.0% used illegal drugs, 17.7% used tobacco products, and 14.1% used alcohol to relieve negative feelings associated with pulling (

2). Additionally, 83% of subjects reported anxiety and 70% reported depression due to pulling (

2). Therefore, clinicians must screen for both trichotillomania and the secondary manifestations if treatment is to be successful.

Differentiating Trichotillomania from Other Conditions

Trichotillomania is often misdiagnosed as OCD. Rates of OCD are significantly higher in individuals with trichotillomania (13%−27%) (

14,

19,

20) than in community samples (1%−3%) (

22,

23), and reported rates of trichotillomania among individuals with OCD have ranged from 4.9% to 6.9% (

24,

25), markedly higher than the range of 0.5%−2.0% observed in the community. The repetitive motor symptoms of hair pulling have some similarity to the repetitive compulsive rituals in OCD (

26). These findings raise the possibility of an underlying common neurobiological pathway, but several lines of evidence suggest that trichotillomania is distinct from OCD. Individuals with trichotillomania are more likely to be female, report higher rates of co-occurring body-focused repetitive behavior disorders such as skin picking or compulsive nail biting, and are more likely to have first-degree relatives with picking or nail biting (

14). Additionally, compulsions in OCD are often driven by intrusive thoughts; by contrast, hair pulling is seldom driven by cognitive intrusions, and obsessional thoughts are not listed in the diagnostic criteria. Whereas trichotillomania symptoms typically begin in early adolescence, OCD symptoms usually begin in late adolescence (

27). Treatment approaches also differ: exposure and response prevention is used for OCD and habit reversal for trichotillomania, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) show efficacy in the treatment of OCD but not, generally, in trichotillomania (

28). (Treatments are discussed in more detail below.)

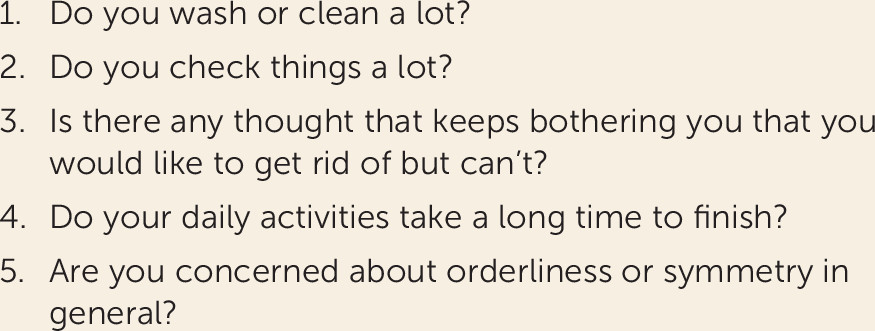

When attempting to differentiate between trichotillomania and OCD, it is important to screen for repetitive hair pulling but also any other repetitive habits. The Zohar-Fineberg Obsessive-Compulsive Screen (

29) (

Figure 2) comprises five short questions, and a positive response to any question indicates that more detailed screening for OCD symptoms is indicated. When OCD is suspected on the basis of the clinical presentation or this screening tool, we recommend administering the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS), including the YBOCS symptom checklist (

30).

Care should also be taken to rule out body dysmorphic disorder, which can mimic trichotillomania. There is a familial relationship between OCD, trichotillomania, and body dysmorphic disorder, so these conditions co-occur more commonly than would be expected by chance (

31). Body dysmorphic disorder is characterized by obsessions about, or a preoccupation with, a perceived defect of one’s physical appearance. Hair pulling can occur in body dysmorphic disorder, but the habit will be motivated by the aim of correcting a perceived physical defect (for example, pulling hair on one side of the head to “correct” what is perceived to be unattractive facial asymmetry), whereas in stand-alone trichotillomania, hair pulling is not undertaken with the aim of correcting a perceived physical defect.

Other mental disorders are also common in people with trichotillomania and should be screened for; comorbidity is the norm rather than the exception (

32). In one study, more than half of patients with trichotillomania reported the lifetime occurrence of an anxiety or mood disorder (

32), and 22% reported a lifetime history of a substance use disorder. When a patient presents with trichotillomania and a substance use disorder, evaluate any possible relationships between the two. In our clinical experience, hair pulling and other types of excessive grooming behavior (skin picking especially) can occasionally be caused by, or worsened by, substance use, including use of stimulants.

Possible Pathophysiology of Trichotillomania

Data regarding the pathophysiology of trichotillomania are limited, but there is a familial component. Several family studies have reported elevated rates of trichotillomania in first-degree relatives of probands with trichotillomania, along with elevated rates of mood and anxiety disorders (

20). In a recent study, Keuthen and colleagues found that the relatives of probands with trichotillomania had higher recurrence risk estimates for hair pulling (

33).

Animal models are a useful tool for investigating the pathophysiology of trichotillomania, particularly those that mimic the behavioral and clinical manifestations of the disorder. Markedly elevated grooming is exhibited in three models in particular: the Hoxb8 knockout mouse (

34), the Sapap3 knockout mouse (

35), and the Slitrk5 knockout mouse (

36). The potential relevance of the SAPAP3 protein in particular to trichotillomania is reinforced by the finding that rare variations in the SAPAP3 gene are associated with human disorders such as hair pulling (

37).

A few small neuroimaging studies have examined possible structural brain findings in trichotillomania, most of which have been region-of-interest studies. A study that measured caudate volumes in trichotillomania patients (N=13) and healthy comparison subjects (N=12) reported no significant between-group differences (

38). Other studies found reduced left inferior frontal gyrus volumes and increased right cuneal volumes in patients with trichotillomania (N=10) compared with healthy subjects (N=10) (

39), smaller left putamen volumes in trichotillomania patients (N=10) compared with healthy subjects (N=10) (

40), and smaller cerebellar volumes in trichotillomania patients (N=14) compared with healthy subjects (N=12) (

41). In a study examining changes across the whole brain, patients with trichotillomania (N=18) exhibited higher gray matter density in several brain regions involved in affect regulation, motor habits, and top-down cognition (left caudate/putamen, left amygdalo-hippocampal formation, left and right cingulate cortex, and right frontal cortex) compared with healthy subjects (N=19) (

42). A separate study found reduced thickness of the right parahippocampal gyrus in patients with trichotillomania (N=17) compared with people with skin picking disorder (N=17) and healthy subjects (N=15) (

43). Interestingly, one study found excess cortical thickness not only in patients with trichotillomania (N=12) but also in their clinically asymptomatic first-degree relatives (N=10) compared with healthy subjects with no known family history of trichotillomania (N=14) (

44). These pilot data hint at a possible familial or hereditary contribution to cortical abnormalities in trichotillomania.

Only two studies have examined whether trichotillomania is also associated with aberrant white matter tracts, using diffusion tensor imaging. In one study (

45), individuals with trichotillomania (N=18), relative to healthy subjects (N=19), showed lower fractional anisotropy in white matter tracts associated with the left and right anterior cingulate cortex, the left and right orbitofrontal cortex, the presupplementary motor area, the left primary somatosensory cortex, and multiple temporal regions. The other study (

46), in 16 people with trichotillomania and 13 healthy subjects, found no overall group differences in diffusion tensor imaging measures. Viewed collectively, white matter connectivity and gray matter volumetric results in these regions, reported in some but not all studies, implicate disorganization of neurocircuitry involved in motor habit generation and suppression, as well as in affective regulation, in the pathophysiology of trichotillomania.

There have been only three functional neuroimaging studies in people with trichotillomania. In the first study (

47), functional MRI and the serial reaction time task were used to assess striatal and hippocampal activation during implicit sequence learning in participants with trichotillomania (N=10) compared with healthy subjects (N=10). The study failed to find any significant differences in implicit learning or in striatal or hippocampal activation, in contrast to positive findings in OCD. The second study (

48) showed dampening of nucleus accumbens responses to reward anticipation (but relative hypersensitivity to gain and loss outcomes) in adults with trichotillomania (N=13) compared with healthy subjects (N=12). Finally, in the only study of children (ages 9–17 years) with trichotillomania (N=9), compared with healthy subjects (N=10), those with trichotillomania exhibited significantly greater activation in the left temporal cortex, the dorsal posterior cingulate gyrus, and the putamen during visual symptom provocation and greater activation in the precuneus and dorsal posterior cingulate gyrus during visual and tactile provocation (

49).

In terms of psychological etiology, it has been suggested that hair pulling may regulate emotional states or stressful events. Hair pulling may function as a means of escaping from or avoiding aversive experiences, and temporary relief from these negative emotions may maintain the behavior through a negative reinforcement cycle (

50). Studies that have measured emotional regulation in individuals with hair pulling found that these individuals have greater difficulty regulating negative affective states than do healthy comparison subjects (

51). Boredom may also trigger pulling in some individuals. This has led some to hypothesize that pulling may similarly help modulate negative emotions brought on by a feeling of perfectionism characterized by unwillingness to relax (

52). This theory suggests that perfectionism leads to feelings of frustration, impatience, and dissatisfaction when standards are not met, particularly when experiencing boredom because productivity is impossible. Hair pulling may therefore function as a means of releasing tension generated by these emotions.