Public perceptions of psychiatry and psychiatrists over time can be traced via community surveys or indirect strategies such as their portrayal in films or television series. Here I consider their characterization in The New Yorker magazine cartoons.

Cartoons, if not simply funny, have an edge often built around a central incongruity.

New Yorker cartoons, in particular, have a recognizable style, with editor David Remnick observing (

1) that they are not only essential to

The New Yorker but “the emblem of the magazine.” They seemingly also carry a New York stamp, characters world-weary, droll, dryly astringent, or alternately, overtly materialistic, smug, or cynical. In a July 2013 TED talk, its cartoon editor Robert Mankoff noted that the stereotypic

New Yorker cartoon not only is playful but also presents a level of incongruity (e.g., polite syntax, rude message) and executes a “benign violation.”

Focusing on mood disorders, I identified 283 cartoons published between 1927 and 2015 capturing psychiatry and psychiatrists. The first cartoon of relevance, published in 1927, depicted Henry VIII disclosing his dream life to a shocked psychoanalyst. Since then, the dominant treatment paradigm has remained psychoanalysis. Psychiatrists (or nonpsychiatrist analysts) were portrayed either in neutral, impassive, or thoughtful poses or negatively—as judgmental, punitive, sarcastic, dismissive, burnt out (even asleep), or simply wacky. Numerous cartoons anthropomorphized analysts and/or their patients, or portrayed them as inanimate objects.

Depression and antidepressant drugs were first specified in the 1980s, and bipolar disorder appeared in the 1990s. Those on antidepressants have fixed grins and are unable to write sad songs or empathize with disconsolate companions. Blasé art gallery observers argue for “more lithium” or observe that a painting, while good, doesn’t quite say “bipolar.”

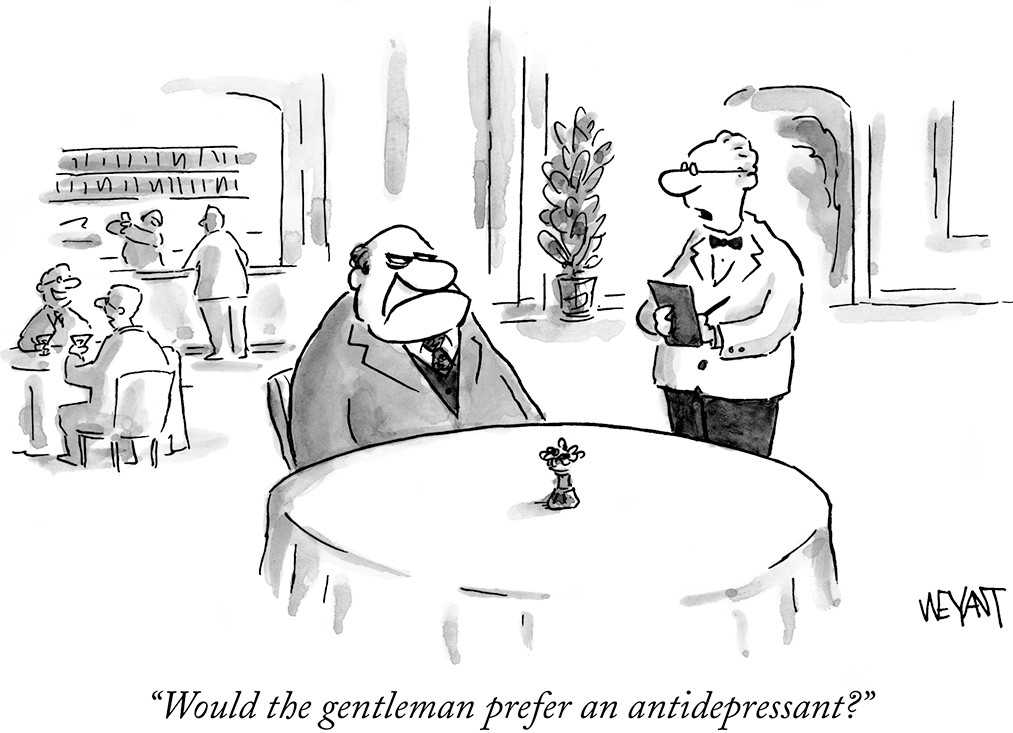

The cartoons capture issues that have dogged psychiatry in recent decades, including the boundaries between clinical and existential depression (with the fine line between sanity and madness having “gotten finer”), between happiness and simply being “asymptomatic,” and between depression and grief. Another common issue is the wider application of antidepressant drugs, as captured in the accompanying cartoon.

Rebecca Mead (

2) noted, “Psychoanalysis continues as a

New Yorker cartoon conceit even after managed care has helped to reduce its widespread practice to a quaint remembrance.” Does the continuing slew of cartoons weighting psychoanalysis reflect its endearment to cartoonists? Or do the couch and analyst provide such immediate symbols for capturing psychiatry that it has become difficult for

New Yorker cartoonists to abandon them? Perhaps psychoanalysis still remains the dominant therapeutic paradigm for New Yorkers themselves? Less likely, has psychoanalysis always been viewed as funny—or more “funny peculiar”—by cartoonists and therefore remains as the archetypal representation for capturing professionals once called “alienists”? Or is it simply that, while psychiatry has moved on in its paradigms and public face,

The New Yorker has successfully remained in a charmed stylistic time warp? Analyze that.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Matthew Hyett and Kerrie Eyers for help in preparing the manuscript.

Cartoon by Christopher Weyant is from The New Yorker Collection/The Cartoon Bank and is used with permission of Condé Nast.