In epidemiological samples, divorce is consistently associated with levels of alcohol consumption and risk for alcohol use disorder (AUD) (

1–

3). Divorced individuals consume more alcohol (

4) and in more harmful patterns (

5) than married individuals. Compared with married individuals, divorcees are more likely to have a lifetime or last-year AUD diagnosis (

1), to engage in alcohol-related risky behaviors (

5), and to have higher alcohol-related mortality (

6).

However, the causes of the divorce-AUD association are likely complex and remain poorly understood. The association could result from confounding factors, including social class, genetic liability, and personality traits that predispose to both AUD (

1,

7,

8) and divorce (

9–

11). This association could also arise from a causal pathway from AUD → divorce as suggested by longitudinal studies showing that heavy-drinking individuals have an increased risk for divorce (

12,

13). Finally, a range of prior evidence suggests a causal divorce → AUD pathway. For example, marriage is associated with many benefits, including spousal monitoring and moderating of one another’s health-related behaviors (

14). Divorce prospectively predicts increases in drinking (

4,

15,

16). A recent Swedish longitudinal and co-relative study showed strong protective effects of first marriage on subsequent AUD risk that, based on results from a co-relative design, were likely to be largely causal (

17).

In the present study, we take complementary analytic approaches to clarify the nature of the divorce-AUD association. We specifically explore the issues described below:

Method

We linked nationwide Swedish registers via the unique 10-digit identification number assigned at birth or immigration to all Swedish residents. The identification number was replaced by a serial number to ensure anonymity. The details of our sources used to create this data set are outlined in the appendix in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article.

Sample

We included individuals born in Sweden between 1960 and 1990 who were both married and residing with their spouse, in or after 1990, with no AUD registration prior to marriage. For the co-relative analysis, we identified full-sibling and cousin pairs from the multigeneration register born within 3 years of each other and monozygotic twin pairs from the Swedish Twin Register (

20).

Measures

For our method of identification of AUD, see the appendix in the

online data supplement. As a measure for socioeconomic status, we used parents’ highest education, categorized as low (compulsory school), mid (upper secondary school), or high (university). Early externalizing behavior was defined as registration before age 19 for criminal behavior or drug abuse using previous definitions (

21,

22). As a measure of familial risk, we assessed whether the individual had one or more parents, full- and half-siblings, or cousins with an AUD registration.

We identified divorce and widowhood by the married status variable in the total population register. Remarriage was defined as first registration of marriage after first registration of divorce or widowhood.

Statistical Methods

We utilized a Cox proportional hazards model to estimate the risk of AUD as a function of divorce or widowhood. As marital status could change over time, we included the predictor variable as a time-dependent covariate, and when estimating the association with divorce, we censored at death, death of spouse, remarriage, migration, or end of follow-up (year 2008), whichever came first. When modeling the effect of widowhood, we censored if divorce preceded the death of the spouse. In our Cox model, we tested the proportionality assumption—that the change in risk for AUD with versus without divorce is constant over the follow-up period. We adjusted for year of birth, externalizing behavior, parental education, familial risk of AUD, and AUD in spouse. We further investigated whether AUD in the spouse affected the association with divorce by including their interaction.

Second, we used a co-relative design to estimate the effect of divorce when adjusting for unmeasured familial confounding. Monozygotic twins share 100% of their genes identical by descent, and full siblings and cousins share on average 50% and 12.5%, respectively, of their genes. Monozygotic twins and siblings typically share their rearing environment. In the co-relative analyses, each pair is treated as a strata, and the hazard ratio represents the increased risk of divorce given the familial confounding shared within pairs. Only pairs concordant for marriage, and discordant for both divorce and AUD, or the timing of divorce and AUD contributed to the estimates. We did not have enough such monozygotic pairs to obtain stable estimates on their own. We therefore built a model in which we included monozygotic twins, full siblings, and cousins and also added the population, treated as one stratum. By assuming that the parameters in the Cox regression (the log of hazard ratios) depend linearly on the genetic resemblance, we obtained estimates for all relative pairs, including monozygotic twins. We compared the fit of this model to a saturated model including a parameter for each relative group by Akaike’s information criteria in which a lower number indicates a better balance of explanatory power and parsimony (

23).

To visualize how the risk of AUD changes around the year of divorce and widowhood, we plotted the proportion of individuals at risk (not censored) at that time point who had an AUD onset at that time. To make a comparison with the nondivorced (or nonwidowed) group, that group’s time of AUD onset was centered on the mean age of divorce (or widowhood) for the corresponding married population. Given the modest number of observations (especially for widowhood), we “smoothed” the curves by presenting 3-year moving averages to all points except the zero point–the year of divorce or widowhood.

Finally, we tested whether a family history of AUD or a history of externalizing behavior prior to age 18 modified the impact of divorce on AUD risk using estimates from an Aalen’s Additive Regression Model (

24), adjusted for birth year and parental education.

Results

Divorce

Our main cohort included 942,366 individuals born between 1960 and 1990 and married in 1990 or thereafter with no AUD registration prior to marriage (

Table 1). The average age at marriage was around 30 years, and AUD onset was 8–9 years later (

Table 1). During our follow-up period, 16% of men and 17% of women were divorced, and 1.1% of men and 0.5% of women were registered for AUD. As seen in

Table 2, using a Cox proportional hazards model with divorce as a time-dependent covariate with birth-year as a control variable, divorce was strongly associated with the subsequent onset of AUD in both men (hazard ratio=5.98, 95% confidence interval [CI]=5.65–6.33) and women (hazard ratio=7.29, 95% CI=6.72–7.91). Adding three key potential confounders, which on their own substantially predicted AUD risk (low parental education, prior deviant behavior, and family history of AUD), produced modest decreases in the observed associations with divorce for men (hazard ratio=5.09, 95% CI=4.81–5.39) and women (hazard ratio=6.31, 95% CI=5.82–6.86). In both males and females, divorce had a much stronger association with risk for future AUD if the spouse did not have a lifetime history of AUD than if they had such a history (males: hazard ratio=−6.05, 95% CI=5.71–6.41 compared with hazard ratio=2.07, 95% CI=1.71–2.52; females: hazard ratio=−7.88, 95% CI=7.20–8.62 compared with hazard ratio=2.38, 95% CI=2.02–2.81).

We then examined the divorce-AUD association in cousins and full-sibling pairs both of whom were married and who were discordant for divorce and compared the results with those observed in the general population (

Table 3 [also see Table S1 in the

online data supplement]). In males, a moderate decline in the association was seen in discordant relative pairs compared with that observed in the general population, with a stronger decline in siblings than cousins. In females, the association was very similar in cousins and the general population but considerably lower in full siblings. In both sexes, the numbers of informative monozygotic twin pairs were too few to provide stable estimates. We then fitted these results to our genetic co-relative model described above, which produced a better fit in both males and females than the saturated model. Using this model, we estimated hazard ratios for the divorce-AUD association in married monozygotic twin pairs discordant for divorce for males and females as 3.45 (95% CI=1.70–7.03) and 3.62 (95% CI=1.29–10.18), respectively. As the large confidence intervals suggest, these estimates were similar across the sexes but were not precisely known.

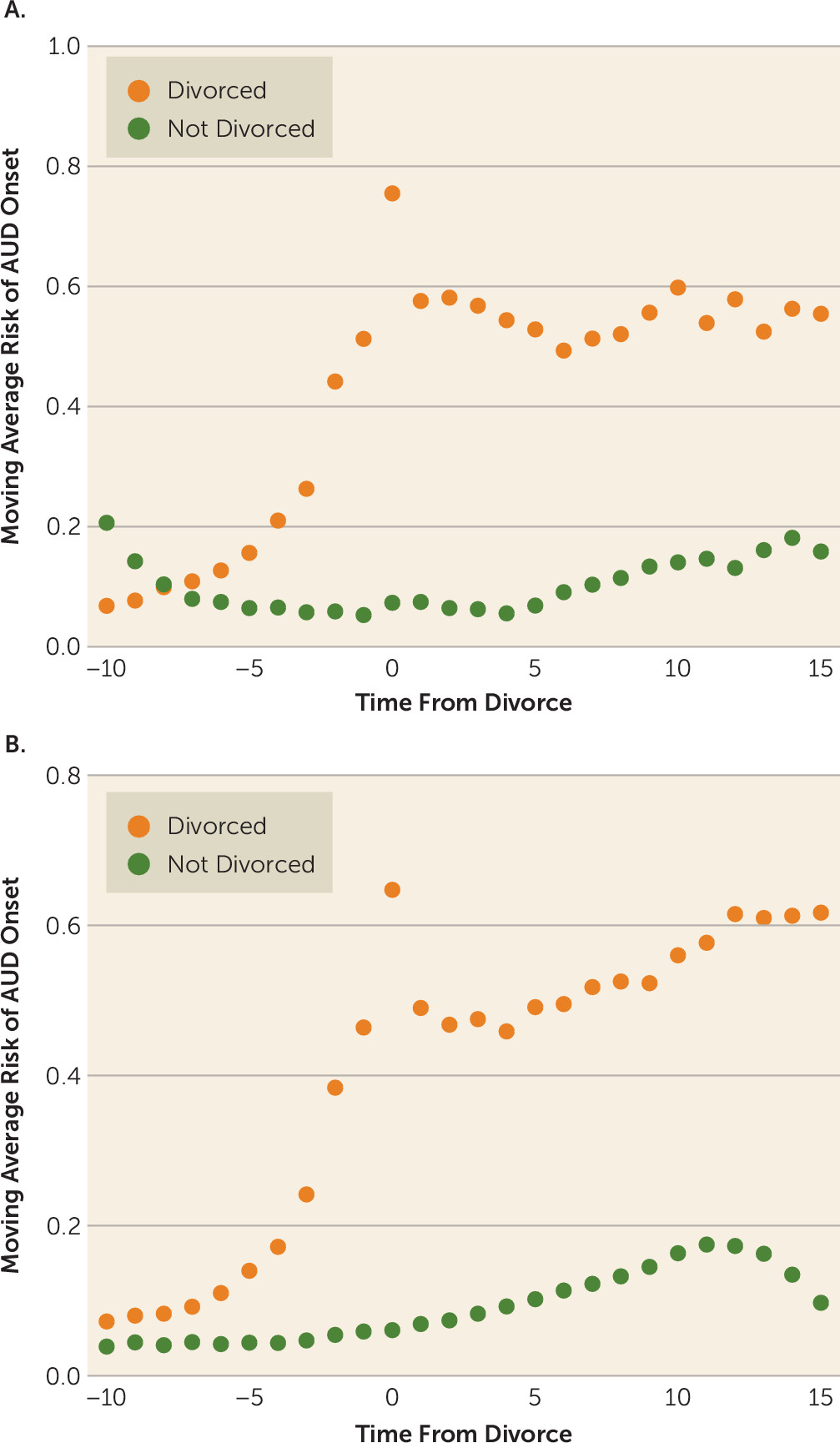

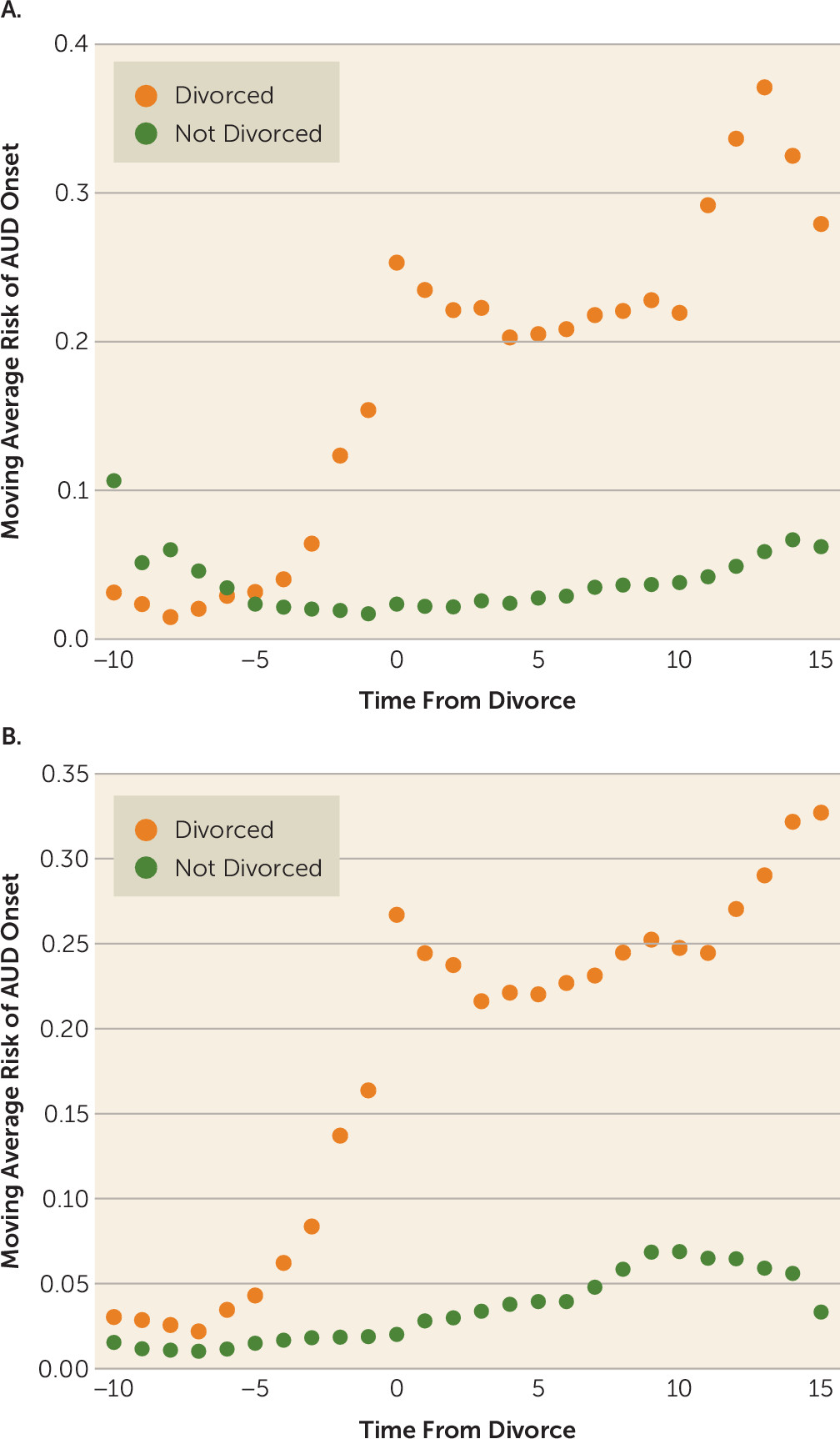

Figure 1A depicts, in males married between the ages of 18 and 25 years (mean age at divorce: 32 years), the prevalence of first AUD registration in the year of the divorce (the zero point in the x-axis) or years earlier and later compared with the base rate of AUD registration in the married population with no divorce. Between 10 and 7 years prior to the divorce, rates of AUD onset are lower or similar for those with and without a future divorce. Then the rate of AUD registration begins to climb in those with a future divorce, peaking in the year of the divorce. The rate of AUD onset then remains substantially elevated for the next 15 years among those who do not remarry, until the end of our observation period.

Figure 1B presents the same analysis on an independent cohort of men married between the ages of 26 and 32 years old, with the mean age at divorce being 39 years old. The pattern of results is similar to that seen in

Figure 1A.

Figure 2A presents results in females married between the ages of 18 and 25 (mean age at divorce=32 years old). Here, the increase in AUD risk occurs only about 3 years prior to the divorce. We see a peak of risk in the year of divorce, with the risk remaining elevated for the next 15 years among those who do not remarry.

Figure 2B shows a similar pattern of results in a different cohort of women married between the ages of 26 and 32, with the mean age at divorce being 36 years old. All four of these figures—showing an increased rate of first AUD registration preceding divorce—suggest that a proportion of the total AUD-divorce relationship in the population arises from AUD predisposing to future divorce.

Our sample contained 9,204 males and 3,835 females with a registration for AUD prior to first marriage, among whom controlling for birth year, divorce was associated with an increased risk of AUD relapse (hazard ratio=3.20, 95% CI=2.86−3.59 and hazard ratio=3.56, 95% CI=2.75–4.60, respectively).

Remarriage After Divorce

Our sample contained 86,698 males and 120,013 females who divorced, of whom 22,874 women and 33,232 males remarried at a mean age of 37.6 years [SD=4.9] and 35.8 years [SD=5.4], respectively. A Cox proportional hazards model with remarriage as a time-dependent covariate demonstrated a substantial decline in risk for first AUD registration in both males (hazard ratio=0.56, 95% CI=0.52–0.64) and females (hazard ratio=0.61, 95% CI=0.55–0.69).

Widowhood

Given the relatively young age of the sample, during our follow-up period, only 0.24% of men (N=1,064) and 0.47% of women (N=2,334) were widowed, with an average age of widowhood around 40 years old (

Table 1). Using a Cox proportional hazards model with death of spouse as a time-dependent covariate and controlling only for year of birth, widowhood was associated with an increased risk for a subsequent first onset of AUD in both men (hazard ratio=3.85, 95% CI=2.81–5.28) and women (hazard ratio=4.10, 95% CI=2.98–5.64) (also see Figures S1A and S1B in the

online data supplement). Adding the same confounders used above for divorce produced modest attenuations in these associations (males: hazard ratio=−3.41, 95% CI=2.49–4.68; females: hazard ratio=−3.64, 95% CI=2.64–5.00). In females only, widowhood had a stronger association with risk for future AUD if the spouse did not versus did have a lifetime history of AUD (hazard ratio=3.69, 95% CI=2.61–5.22 compared with hazard ratio=1.17, 95% CI=0.52–2.65). Widowhood was too rare to permit co-relative analyses.

Modifiers

In males and females, the yearly increased risk for AUD onset after divorce was 0.24 and 0.10, respectively, in those without a family history of AUD, and it was significantly higher in men and women with a family history (0.51 and 0.25, respectively; both p values <0.0001) (see Figures S2A and S2B in the online data supplement). In those without externalizing behavior prior to age 18, the yearly increased AUD risk after divorce was 0.29 and 0.15 in males and females, respectively, and increased significantly (both p values <0.0001) to 0.75 and 0.39, respectively, in those with an externalizing history prior to marriage (see Figures S3A and S3B in the online data supplement).

Discussion

The goal of these analyses was to clarify the magnitude and nature of the association between divorce and onset of AUD. To do so, we performed seven sets of analyses that we examined in turn.

Our first goal was to quantify, among individuals with no AUD prior to marriage, the prospective relationship between divorce and subsequent onset of AUD. We found strong associations, with the rates of first onset of AUD increasing after divorce around sixfold in men and over sevenfold in women. Our results are comparable with two prior prospective studies in both sexes. In a Dutch general population sample, divorce predicted a strong excess of subsequent alcohol abuse (odds ratio=3.9) (

16). In a longitudinal study from a Michigan HMO, the risk ratio for “alcohol disorder symptoms” after divorce was substantially elevated (6.6) (

25). While these prospective analyses, which document a robust association in the Swedish population between divorce and AUD onset, are consistent with a causal impact of divorce on AUD, it is plausible that a range of confounding variables might be responsible for some or all of this observed association.

Our second set of analyses therefore added to our predictive models three potentially key confounding variables that all robustly predicted risk for AUD: socioeconomic status during child rearing, predisposition to externalizing psychopathology, and familial risk for AUD. Their addition modestly attenuated the prior associations with hazard ratios by approximately 15%.

Our third set of analyses used a complementary approach to clarifying the sources of the divorce-AUD association. Instead of specifying individual confounders to be controlled statistically, the co-relative approach, in which we compare the risk for AUD in pairs of married relatives discordant for divorce, controls for all familial confounding traits and behaviors. This is a powerful approach because the vast majority of human behavioral traits are correlated in family members (

26) and the individual traits need not be specified or even known. For causal inference, the most informative relative pair is married monozygotic twins where one has divorced and the other has not, as these twins share all their genes at conception and are reared in the same environment. Such twins were too rare even in our large Swedish samples to generate stable statistical estimates. However, we developed a simple model in which the results across a range of pairs of relatives including monozygotic twins can be estimated from observed data. In males, we found, as expected, that the observed hazard ratio between divorce and AUD was highest in the general population, modestly lower in discordant cousins, and moderately lower still in discordant full-siblings. From these results, we could predict, in a model that fitted the data well, that the hazard ratio for AUD in married monozygotic pairs discordant for divorce declined 42% from that in the general population. The results from females were similar, with a slightly greater decline in the divorce-AUD association from the population to discordant monozygotic twins of 51%. This pattern is consistent with the interpretation that the association between divorce and AUD is in part causal and in part due to confounding familial factors, consistent with results from a previous study of Australian twins (

27).

Our fourth set of analyses examined closely the temporal patterning of onsets of AUD with respect to the time of divorce. Looking at two cohorts married at ages 18–25 and 26–35 separately in males and females, we saw broadly similar patterns. Not unexpectedly, an increased risk for AUD onset began a few years prior to the divorce, which is consistent with marital dissolution reflecting a process rather than just a discrete event (

28). But in both sexes and in both age groups, the risk for AUD increased substantially in the year of the divorce and remained elevated for many years in those who did not remarry. Fifth, we showed that in individuals with an AUD registration prior to marriage, divorce increased the risk for an AUD relapse, although with a smaller effect size than for a first onset.

Our sixth set of analyses followed up on our previous examination of the substantial reduction in risk for onset of AUD in single individuals who marry for the first time (

17). We reasoned that if the association between marital status and AUD risk was truly causal, remarriage after divorce should also convey protective effects. This was indeed what we found, although the protective effect of marriage was more modest than that found previously in single individuals, both in males (0.56 compared with 0.41) and females (0.61 compared with 0.27) (

17).

Finally, since drinking problems can themselves contribute to divorce, we wanted to examine how another form of spousal loss, widowhood, would affect AUD risk. Given the relative youth of our sample, widowhood was rare but was nonetheless strongly associated with an increased risk for AUD in both males and females. This is consistent with previous findings showing that bereavement is associated with prospective increases in drinking (

29) and excess alcohol-related mortality (

30). These associations were weaker than seen with divorce in both sexes but also attenuated less with the addition of covariates. This would be the expected pattern if the proportion of the association between spousal loss and AUD due to causal factors was greater for widowhood than divorce. While the data were sparse, the temporal pattern of the onset of AUD in association with widowhood was consistent with an association that was largely driven by causal and long-lasting effects (see Figures S1A and S1B in the

online data supplement).

We found, in both sexes, a much larger effect on risk for AUD of divorce when the spouse did not versus did have a history of AUD. We saw a similar effect with widowhood but only in females. These results suggest that it is not only the state of matrimony and the associated social roles that are protective against AUD (

31). Rather, they are consistent with the importance of direct spousal interactions in which one individual monitors and tries to control his or her spouse’s drinking (

14). A non-AUD spouse is likely to be much more effective at such control than a spouse with AUD.

Limitations

These results should be interpreted in the context of three potentially important methodological limitations. First, we detected individuals with alcohol use disorder from medical, legal, and pharmacy records and thus did not require respondent cooperation or accurate recall. Compared with structured interviews, however, this method surely produces both false negative and false positive diagnoses. Given that the population prevalence of AUD in our sample is considerably lower than that found in interview surveys (

1,

32) (including in next-door Norway) (

33), false negative diagnoses are likely much more common and severity of cases more severe. The validity of our AUD definition is supported by the high rates of concordance observed across our ascertainment methods (

34).

Second, our examination of the temporal patterning of spousal loss and AUD onsets with respect to the time of divorce did not account for leftward censoring, that for some couples, the time between marriage and divorce was short. We reran all our analyses only on the subgroup of spouses married at least 5 years prior to divorce, with only very modest changes in the pattern of results.

Third, our choice of cohort (born between 1960 and 1990, married after 1989, studied until 2008) was a compromise that maximized our sample of married individuals (missing a few with early marriage) who subsequently divorced (missing a few with late divorce.)