The classic nosologic divide in psychiatry has been between neurosis and psychosis. The two were originally conceptualized as distinct categories of mental illness, and it was only the odd (irreverent!) case that “tipped over” from the former to the latter. Extensive research over the past decade and a half has upended this notion, blurring previously sharp diagnostic boundaries, reframing psychosis as a continuum and casting the relationship between neurosis and psychosis in a very different light.

A continuum approach to psychosis grew rapidly in prominence around the turn of the 21st century (

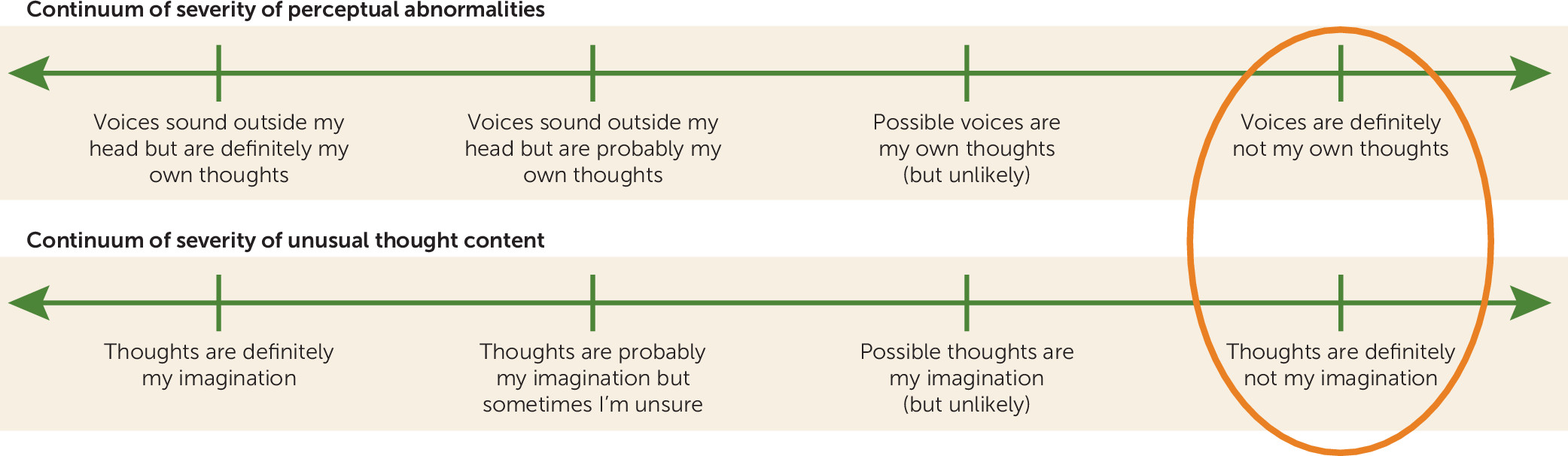

1). Recognizing that hallucinations and delusions occur across a spectrum of intensity and severity in the population, researchers began to explore the occurrence of psychotic symptoms outside the context of psychotic disorder. The term “psychotic experiences” was adopted to describe these phenomena at a population level. It referred to perceptual abnormalities and unusual thought content that were phenomenologically akin to the hallucinations and delusions experienced in psychotic disorders but were typically associated with at least some degree of intact reality testing (i.e., the individual recognized these experiences as a product of his or her own mind) (

Figure 1).

Psychotic experiences emerged as a rather prevalent phenomenon, with epidemiological studies finding that approximately 7% of the general adult population reported them (

1). Psychotic experiences were not, however, distributed randomly in the population; rather, research began to show that they clustered with general measures of nonpsychotic psychopathology (

2). Many studies (of seemingly disparate mental disorders) found the same thing: psychotic experiences occurred at high prevalences across the diagnostic spectrum.

This finding is elegantly demonstrated by McGrath and colleagues in this issue of the

Journal (

3) using data from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey, a unique cross-national sample of 31,261 adults in 18 countries. The researchers looked at the relationship between psychotic experiences and 21 mental, behavioral, and addiction disorder diagnoses, divided into five categories: mood disorders, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, impulse control disorders, and substance use disorders. Far from being restricted to psychotic disorders, psychotic experiences were predicted by all mood disorders, all anxiety disorders, and all eating disorders.

Psychotic experiences were also predicted by three of four impulse control disorders—attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder, although not conduct disorder. The lack of relationship between conduct disorder and psychosis is intriguing. What are the implications for how we conceptualize conduct disorder when it alone among the mental and behavioral disorders has no apparent psychotic dimension? How does it fit with the other disorders with which it is listed in DSM? It is a thought-provoking finding and one worthy of further study.

Within the final category of disorders (addictions), psychotic experiences were predicted by alcohol abuse and dependence but, curiously, not by drug abuse or dependence. Taken against a backdrop of extensive research demonstrating psychotogenic effects of cannabis and many other substances, this is an unexpected finding. Overall, though, what the results clearly demonstrate is that psychosis emerges in a proportion of illnesses right across the diagnostic spectrum.

Of note, the chapters on depressive and bipolar disorders in DSM-5 do include the specifier “with psychotic features.” However, psychotic experiences typically do not meet the threshold of fully impaired reality testing, which is necessary for the experiences to be considered fully psychotic. Therefore, even in the case of depressive and bipolar disorders, the “with psychotic features” specifier is typically not applicable to individuals who have psychotic experiences. This leaves a major gap in the recognition of the presence of “broad” psychosis in the spectrum of (ostensibly) nonpsychotic mental disorders.

Does any of this have clinicopathological significance? Or is the presence of psychotic experiences in nonpsychotic mental disorders only of interest to pedantic psychopathologists? In fact, we have long argued that psychotic experiences represent transdiagnostic clinical markers of psychopathology severity, and a growing body of data supports this position. Research has shown, for example, that psychotic experiences, when present in individuals with neurotic disorders, predict poorer illness course (

4), poorer socio-occupational functioning (

5), poorer neurocognitive functioning (

6,

7), more multimorbid psychopathology (

5), and higher risk for suicidal behavior (

8). Accurate assessment and clinical documentation of psychotic experiences, then, is not just a matter of nosologic pedantry but of substantial prognostic importance.

While we consider the broader presence of psychosis in neurotic disorders, it is also important to reflect on the corollary—neurosis in psychotic disorders. Diagnostic hierarchy rules are often used to exclude “neurotic” diagnoses in patients with schizophrenia. For example, symptoms that would in their own right fulfill a diagnosis of depression are often instead reframed as negative symptoms of psychosis (

9). This practice overlooks the fact that depressive disorders are in fact common in psychosis (indeed, Upthegrove and colleagues recently argued that depression may in fact be a core feature of psychosis, lying on the severe end of a dimension of affective dysregulation [

9]) and warrant treatment—be it psychological, pharmacological, or both. What is more, research has shown that treatment of nonpsychotic disorders in individuals with schizophrenia can lead to improvements not only in the neurotic disorder itself but also in schizophrenia. De Bont et al. (

10), for example, recently demonstrated that treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in individuals with psychotic disorders, compared with treatment of psychosis alone, led to high rates of remission from PTSD but at the same time led to increased rates of remission from schizophrenia itself. This finding demonstrates the importance of identifying and treating comorbid disorders in individuals with psychotic illnesses. We are quick, it must be noted, to recognize comorbid substance use disorders in psychosis—it is time that we became equally adroit at identifying (and treating) comorbid affective, anxiety, and trauma- or stressor-related disorders.

The time has come to look beyond the idea of psychosis as a distinct category of mental illness, separate from other mental disorders. An overwhelming wealth of research now supports the idea that psychosis may in fact be a feature of mental disorders right across the diagnostic spectrum. Psychosis does not fit neatly into one section of DSM; on the contrary, it should have a place in every chapter.