Irritability is among the most common reasons that children are brought for psychiatric evaluation and care (

1,

2). While irritability has received increased research attention over the past two decades (

3), few effective treatments are available. Given its public health importance (

1,

2,

4–

6) and the dearth of evidence-based treatments (

7–

9), developmentally sensitive pathophysiological models are needed to guide novel therapeutics for irritability. We present a mechanistic model of irritability that integrates clinical and neuroscientific research and has implications for treatment development.

First, we review the definition, longitudinal course, and prevalence of irritability. Next, we describe two conceptualizations of irritability based in translational neuroscience: 1) aberrant responding to blocked goal attainment (

10) and 2) aberrant approach responding to threat (

11). We link these two constructs in one overarching mechanistic model of irritability. Since irritability shows significant cross-species conservation of brain-behavior relationships, our translational model synthesizes neural, behavioral, and clinical data across human and animal research. Finally, after briefly reviewing data for existing treatments, we discuss ideas for novel, mechanism-based interventions.

We reviewed the literature prior to October 2016 using the search terms “irritability,” “anger,” and “frustrative nonreward.” Overall, 163 papers were included in the review: 14 animal studies, 71 human experimental studies, and 78 clinical studies. We focus on studies of irritability, severe mood dysregulation, and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD). We also include studies on related clinical constructs, including externalizing or disruptive behavior disorders (defined here as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder). Thus, our model and its clinical implications are specifically targeted toward youths with DMDD or those with disruptive behavior disorders who exhibit chronic irritability.

Clinical Definition, Longitudinal Course, and Prevalence

Irritability can be defined as an elevated proneness to anger relative to peers (

12,

13). Proneness to anger is a trait that is distributed continuously in the population (

14) and expressed stably across time (

15). Proneness to anger is a dimension, and the precise cut-point demarcating normality from pathology varies developmentally (

16). In this review, we focus on relatively severe manifestations of childhood irritability, that is, those that cause impairment and therefore necessitate treatment.

The DSM-5 criteria for DMDD represent one approach to operationalizing

severe irritability in youths (

17). Indeed, among children with oppositional defiant disorder, only those whose irritability severity is within the top 15% would meet criteria for DMDD (

17). Youths with DMDD exhibit severe and recurrent temper outbursts that are more easily elicited, longer lasting, and contextually atypical relative to those of their peers (

16,

18–

20). Relative to peers, irritable youths have a lower threshold for expressing anger, leading to more frequent temper outbursts; when such outbursts occur, they have greater behavioral intensity (

12,

13,

21). Outbursts are characterized by motor activity, prominent displays of anger and other negatively valenced emotions, and verbal as well as sometimes physical displays of reactive aggression (

22). Between temper outbursts, severely irritable children also have a persistent angry

mood, involving sullen nonverbal behaviors and reports of being annoyed over many days. Thus, DMDD includes affective and behavioral components, and our pathophysiological framework integrates both of these dimensions. However, it is important to note that the available data are equivocal as to whether temper outbursts and between-outburst negative mood are separable components (

14).

The normative threshold, frequency, and behavioral manifestations of anger change over the course of development (

23–

27); for this reason, the criteria for DMDD stipulate that temper outbursts have to be inconsistent with developmental level (

14,

16,

18,

23). For example, irritable behavior that would be normative in the preschool years or in early childhood (e.g., short-lived temper tantrums multiple times per week) could be abnormal in middle childhood. Retrospectively reported clinical data suggest that the average age at onset of DMDD symptoms is 5 years (

3). However, because normative irritability peaks in the preschool years, the determination of a cut-point for psychopathology at that developmental phase is particularly challenging (

14,

16,

18,

23). Therefore, DSM-5 does not allow the diagnosis to be assigned until age 6.

Clinically impairing irritability in children and adolescents began to gain more attention as interest grew in the diagnosis of pediatric bipolar disorder. Beginning in the 1990s, child psychiatry researchers suggested that while pediatric bipolar disorder can present with distinct episodes of mania or hypomania as in adults, the more typical pediatric presentation was chronic, severe irritability and hyperarousal symptoms (

28,

29). However, a series of longitudinal (

30), family (

31), behavioral (

32–

34), and pathophysiological (

35–

38) studies differentiate classically defined episodic pediatric bipolar disorder from chronic irritability without distinct manic or hypomanic episodes (operationalized as severe mood dysregulation [

28]) (

3). For example, behavioral and functional MRI studies have found that while both youths with bipolar disorder and those with severe mood dysregulation have impairments in labeling face emotions (

32,

33), the neural correlates of this deficit differ between the two groups (

38–

40). Indeed, more recent evidence indicates that the pathophysiological correlates of the

trait of irritability itself differs between bipolar disorder and DMDD (

40). Thus, the latter study addresses the pathophysiological specificity of DMDD and bipolar disorder while also demonstrating that the brain mechanisms mediating irritability may differ across diagnoses.

Among the several strands of research designed to differentiate pediatric bipolar disorder from chronic irritability, longitudinal studies provide the strongest evidence that these two phenotypes are distinct entities. Children with chronic irritability (including when it occurs in the context of oppositional defiant disorder) are at elevated risk for later depression and anxiety, but not manic episodes (

12,

30,

41–

45). Importantly, high levels of childhood irritability also predict increased risk for suicidality (

4,

5) and functional impairment in adulthood (

41,

46,

47). Such longitudinal data have heightened interest in the study of irritability, including research on clinical phenotyping, behavior, and pathophysiology. However, treatment research remains limited.

Prevalence estimates of severe irritability in community samples of children and adolescents range from 0.12% to 5% (

48); 3% is the most common prevalence estimate for DMDD (

46,

49) or severe mood dysregulation (

43). The considerable disparity in frequency estimates results from the fact that studies vary in the extent to which they adhere to DSM-5 criteria regarding frequency of outbursts, duration of irritability, impairment, and the exclusion of individuals with mania or hypomania (

4,

48). Of note, in these studies the criteria operationalizing irritability were generated post hoc. Not surprisingly, in clinically referred samples (

26,

50), the rate of DMDD is higher than in epidemiological studies. To obtain valid, developmentally informed prevalence estimates of chronic, severe irritability, it is critical to assess youths prospectively over time (

24,

25,

49).

Aberrant Responding to Frustrative Nonreward

In rodents, Amsel (

10) described frustrative nonreward as an adaptive, normative response to blocked goal attainment. Frustrative nonreward also is a negative valence construct in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) (

53). The term describes the emotional state induced when an animal learns to expect a reward, such as food, and it is not delivered. The induction of this state elicits a range of responses (

54). In rodents, the typical frustrative nonreward response consists of increased motor activity and aggression (

10,

55). Evolutionarily, increased motor vigor allows for the mobilization of resources to overcome physical obstacles or other organisms and thereby acquire the reward. The utility of frustrative nonreward as the basis for translational research on irritability (

53) is supported by the observation of increased motor activity following unexpected reward omission in rodents (

10,

55), nonhuman primates (

56), children (

57), and adults (

58). Frustration induction paradigms that involve deliberate, repeated blocked goal attainment can be administered cross-species.

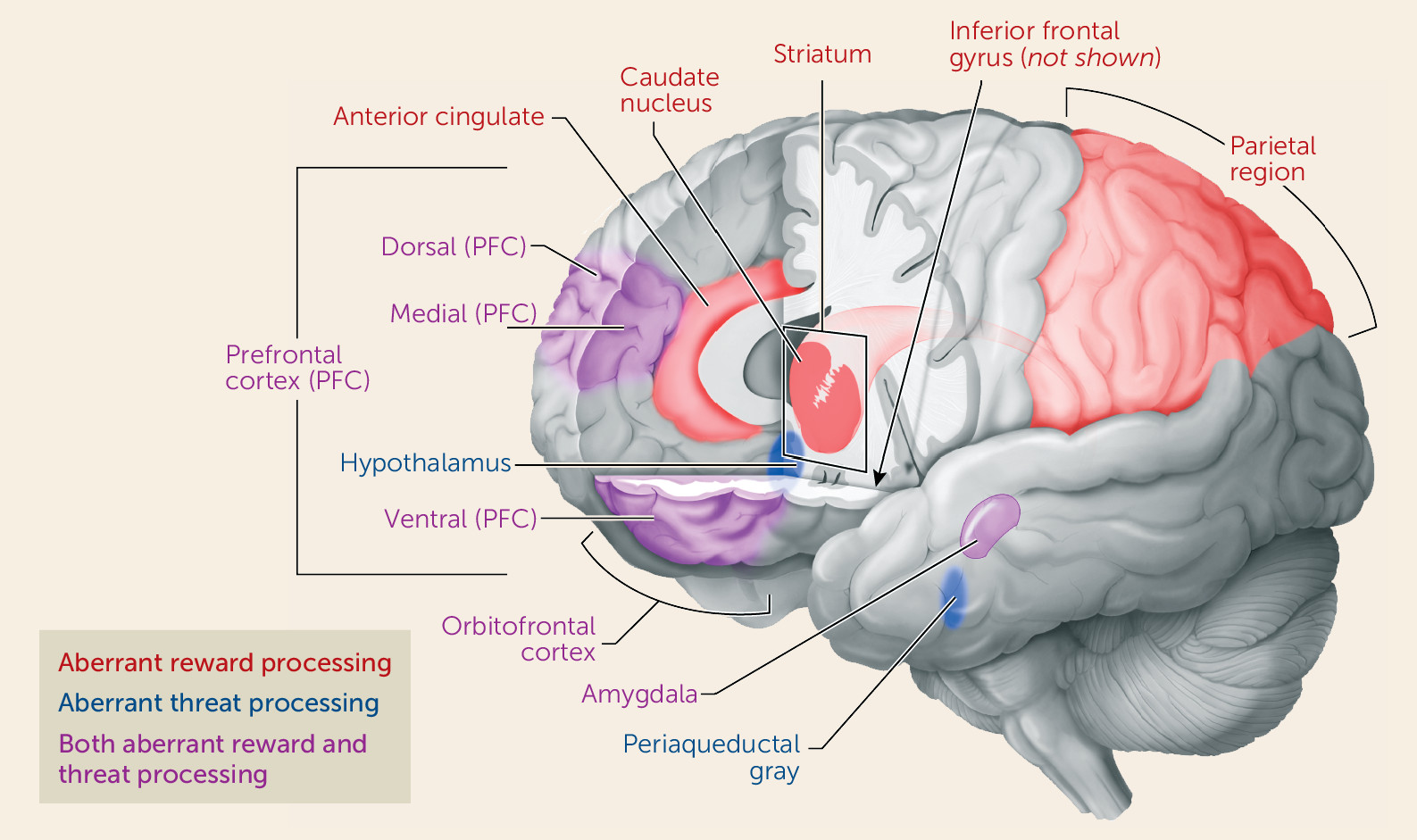

While animal research describes normative responses to frustrative nonreward, human research suggests that higher levels of irritability are associated with a lower threshold for experiencing frustrative nonreward and a greater magnitude and duration of responding. Responses to frustration are mediated through neural circuits associated with reward processing, involving the prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex, the striatum, and the amygdala (

59–

61). Brain imaging research links maturation of these circuits to improved executive functioning and emotion regulation (

62–

64). Such developmental processes may support the normative developmental trajectory of irritability, described above. Specifically, over the preschool to school-age period, healthy children learn to inhibit outbursts in response to frustration and to employ other, more effective strategies to achieve their goals (

65). As healthy children develop more self-control and better frustration tolerance, the behavior of age-mates who persist in exhibiting significant irritability and oppositionality becomes increasingly aberrant from a developmental perspective.

Aberrant Approach Toward Threat

Threats are stimuli that signal circumstances with an increased possibility of harm for an organism. Threat responding is mediated by an established circuit involving the prefrontal cortex, the amygdala, the hypothalamus, and the periaqueductal gray. In healthy organisms, engagement of this circuit occurs in a graded fashion, based on the proximity of the organism to a threat (

66). This normative behavioral cascade of threat responses involves vigilance for distal threats, freezing and other behaviors designed to avoid detection when threats are somewhat closer, and flight or attack behavior in response to proximal threats (

67,

68). In this final stage, whether responding involves flight or attack depends on the context and characteristics of the threat (

11,

69–

71). Imminent inescapable threats elicit anger or rage (

71), emotions associated with

approach behavior and active engagement with the threatening stimulus in an attempt to neutralize it (

72). Over development, both the stimuli deemed threatening and responses to those threats change; for example, while crying during separation from a caregiver is normative for babies, it is not for adolescents (

73). Youths with irritability show a relatively low threshold for both threat detection and fight/attack (relative to flight/avoid) responding (

74). Thus, while angry approach behavior may be adaptive in the context of unambiguous, inescapable, imminent threats, aberrant processing of threat stimuli (e.g., perceiving a benign stimulus as threatening, engaging in a limited range of responses) may lead to maladaptive aggressive responding.

Treatment Implications

This pathophysiological model suggests novel approaches to treating irritability by addressing the two domains of dysfunction described here. It remains unclear whether the pathophysiology of irritability differs transdiagnostically and in the context of co-occurring symptoms (e.g., anxiety). However, early evidence suggests that the neural correlates of irritability differ in the context of DMDD and bipolar disorder (

40) and across differing levels of anxiety (

125). This may have significant treatment implications.

Based on our model, we propose that treatments could target reward processing dysfunction, with a focus on correcting deficits in the content and process of instrumental learning, and on decreasing sensitivity to reward omission (

138,

147). Indeed, pilot data suggest that interventions targeting aberrant responding to threat may decrease irritability (

123). Pharmacological interventions for irritability, including stimulants (

148), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (

149,

150), and atypical antipsychotics (

151), have shown promise in the treatment of aggression and irritability. Current NIMH-funded studies (

ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT00794040, NCT01714310) are examining the combination of a stimulant plus an SSRI in the treatment of severe mood dysregulation. Below, we focus on novel psychological approaches suggested by our pathophysiological model; however, such work could be extended to pharmacological treatments (

152).

Pilot data support further testing of computer-based cognitive interventions for irritability. Based on work documenting irritable youths’ propensity to interpret faces and social situations as hostile and a treatment trial by Penton-Voak et al. (

153), Stoddard et al. (

123) trained irritable youths to report a more positive, less hostile interpretation of ambiguous faces. This intervention was associated with decreased irritability. A randomized trial is under way (

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02531893) that includes imaging of face emotion processing before and after treatment. Also, in anxiety disorders, attention bias training can decrease the automatic attentional processes to threat (

154,

155); whether such training would decrease irritability is unknown.

Similar to computer-based interventions designed to alter subjects’ perceptions of ambiguous faces, the theory behind cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for aggression and irritability evolved from social learning and social information processing models. From this perspective, irritability arises from maladaptive and hostile interpretations of social situations with peers and adults (

9,

156,

157). Using learning principles and structured strategies, CBT is designed to decrease hostile interpretations of situations, provide alternative coping skills, reduce aggressive behaviors, and increase self-efficacy. Sukhodolsky and Scahill (

156) developed a manualized CBT for anger and aggression in children that emphasizes social problem-solving skills; while its focus is on individual treatment with the child, there are some parent-focused sessions as well (

158). Consistent with the model we describe, these investigators predict that a reduction in reactive aggression after CBT will be associated with decreased amygdala activation and increased dorsal anterior cingulate and ventromedial prefrontal cortical activation during frustration (

157). In addition, Waxmonsky et al. (

8) recently developed a parent and child group psychotherapy to improve irritable children’s ability to assess the potential consequences of their behavior before responding to social situations and thus select more adaptive behaviors. Early work demonstrates the feasibility of this approach.

Given threat processing anomalies in irritable youths, the pathophysiological overlap of irritability with anxiety, and the efficacy of exposure techniques in treating anxiety, another novel treatment for irritability would test whether exposure to frustrating contexts may be an effective intervention for irritability. In the treatment of anxiety disorders, exposure techniques are used to extinguish fear responses. Such techniques help patients gradually confront and tolerate stimuli that they perceive as threatening. In children and adolescents with irritability, exposure might include stimuli or situations that evoke frustration, anger, and temper outbursts. Exposure for irritability in youths has yet to be tested and will likely lead to complex clinical challenges in safely evoking anger in irritable patients. Of note, while some have questioned the rationale and efficacy of exposure techniques in the treatment of anger (

159), early open pilot work in small samples of adults (

160) is promising. Given the dearth of effective treatments for irritability in youths, and based on the pathophysiologic model proposed here, we suggest the importance of studying a novel intervention for irritable youths that would incorporate parenting training and therapeutic exposure to anger-inducing stimuli.

Conclusions

This translational neuroscientific model synthesizes the literature relevant to irritability in youths, organizing neurobiological and behavioral findings into two overarching domains, namely, deficits in reward and in threat processing. Our model suggests how deficits in these two domains may interact to produce the clinical phenotype in youths.

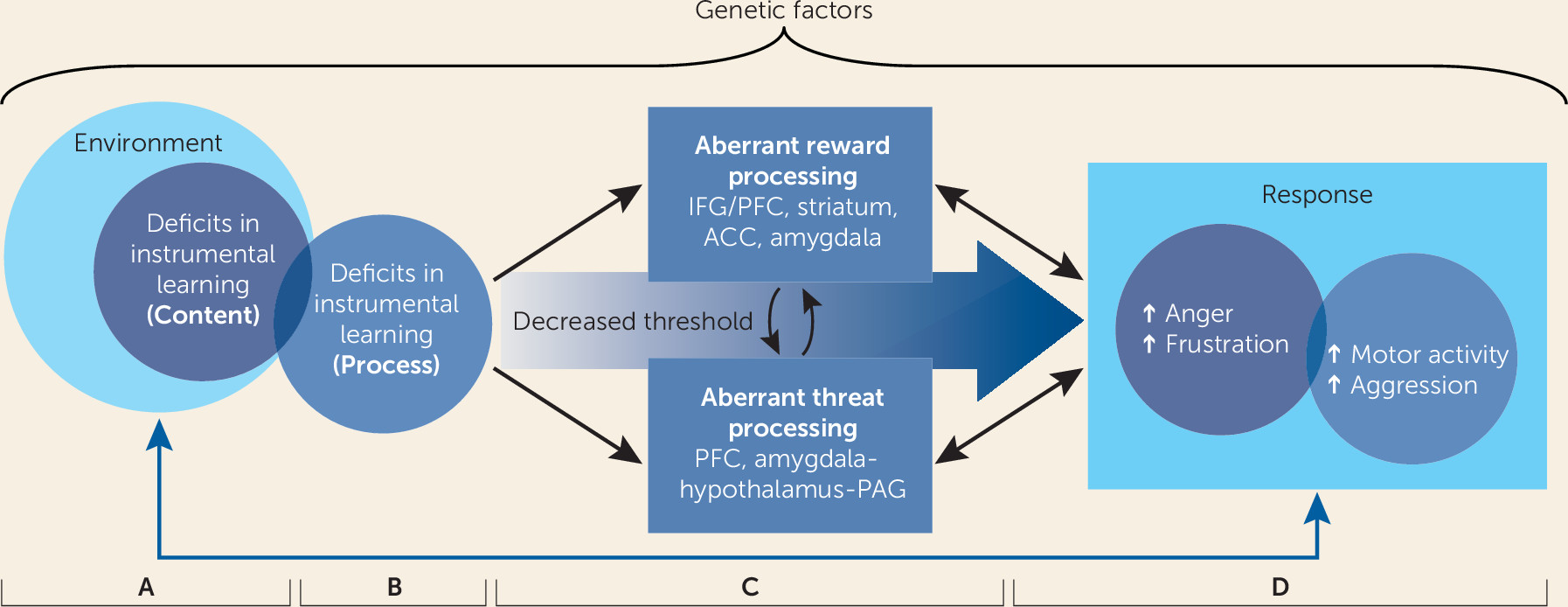

First, we propose that impairments in reward processing are associated with aberrant responses to frustrative nonreward and with irritability (see

Figure 1, panel C). Both neurobiological and behavioral research has shown that irritable youths have difficulties modifying their behavior in accordance with stimulus-reward associations, learning from their behavioral errors, and adapting their behavior in response to changing contingencies in order to optimize reward receipt. Irritable children’s difficulties predicting and adapting to their external environment puts them at high risk for experiencing frustrative nonreward. Moreover, rewards and reward omissions themselves may be more salient to irritable children than they are to healthy peers. When frustrative nonreward does occur, irritable youths may exhibit a heightened magnitude and duration of responding.

Second, we assert that irritability is associated with heightened orientation to threat in the environment, stronger threat-based interpretation of ambiguous and neutral stimuli, and deficits in correctly identifying face emotions (see

Figure 1, panel C). That is, youths with irritability have a lower threshold for perceiving stimuli as threatening, in addition to a lower threshold for aggressive responses. These maladaptive behaviors are associated with amygdalar and prefrontal cortical dysfunction. Thus, we encourage clinicians working with highly irritable children and adolescents to explore associations between perceived threats and temper outbursts. We present evidence that deficits in threat and reward processing interact (

55) (see

Figure 1, panel C). For example, in animals, frustrative nonreward potentiates threat approach, and threat potentiates frustrative nonreward. Clinically, an irritable child may be particularly prone to perceiving a stimulus (e.g., a parent’s neutral facial expression) as threatening in the context of frustrative nonreward (e.g., as the parent is saying “no”), increasing the propensity to respond with a temper outburst.

Our review suggests specific research directions. First, although the measurement of irritability has improved (

161), there are important areas for development. For example, the “peak-end” rule, a well-known phenomenon in clinical assessment, may bias reports of irritability. That is, children and their parents may tend to recall and rate symptoms based on their most severe (i.e., “peak”) and most recent (i.e., “end”) presentations (

162), thus introducing systematic bias. Therefore, current methods for characterizing irritability may be improved through the use of ecological momentary assessment techniques, in which informants report on symptoms in real time within their naturalistic settings. Ecological momentary assessment studies could also clarify whether temper outbursts and between-outburst negative mood are indeed distinct constructs. Although the DSM-5 criteria for DMDD require both clinical presentations, the existing data as to whether they are dissociable are limited and equivocal (

14,

148).

Second, the study of irritability provides tractable targets for novel behavioral and neuroimaging paradigms. Paradigms should be developed to examine the consequences of acute frustration on reward and threat processing. For example, baseline instrumental learning deficits in chronically irritable youths may be exacerbated during the acute state of frustration. Similarly, when frustrated, irritable youths may perceive ambiguous or even positive stimuli as more threatening or hostile (

39,

123). Of course, while there are clear advantages to probing frustration directly in children with irritability, there are also inherent difficulties. It is challenging to develop affectively salient tasks (

35,

60,

97), and it can be difficult to disentangle frustration-related deficits from various confounders (e.g., time from baseline spent on a task, fatigue). In addition, such paradigms typically require deception in order for frustration to occur, raising both ethical and logistical issues.

Finally, the conceptualization of two core pathophysiological mechanisms in irritability, reward-based and threat-based, raises intriguing questions regarding subtypes that would have treatment implications. Possibly, irritable youths could be characterized as those with relatively more prominent reward-based dysfunction versus more prominent threat-based dysfunction. Tasks designed to test interactions of threat and reward processing would also help to clarify the extent to which threat stimuli potentiate dysfunction in reward processing and vice versa. Personalized psychological treatments could address reward and/or threat processing deficits, with varying “doses” of a specific treatment component prescribed on the basis of pretreatment assessments (

163). For example, youths with heightened reward (relative to threat) sensitivity may benefit from more targeted parenting interventions, whereas those with more profound threat processing deficits may find computerized attention or interpretation bias interventions (

155) or exposure-based treatments more effective. Based on the current literature demonstrating the efficacy of parenting interventions (

140–

143), we suggest that a combination of parenting and threat-based targeted interventions will be most effective in the comprehensive treatment of severe irritability in youths. Future work is encouraged to test the hypothesized pathways in the model and novel targeted interventions. Precise phenotypic and pathophysiological characterization will ultimately lead to more effective treatments for severe and impairing irritability in youths.