DSM-5 describes the primary criterion of mania as being “a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood”

and “abnormally and persistently increased goal-directed activity or energy.” One of our forefathers of psychiatric phenomenology, Emil Kraepelin, referred to this phenomenon a century ago, suggesting that “increased busyness” was the most striking feature of mania (

1). He elegantly described it as follows:

The patient feels the need to get out of himself, to be on more intimate terms with his surroundings, to play a part. As he is a stranger to fatigue, his activity goes on day and night; work becomes very easy to him; ideas flow to him. He cannot stay long in bed; early in the morning, even at four o’clock he gets up, he clears out lumber rooms, discharges business that was in arrears, undertakes morning walks, excursions. He begins to take part in social entertainments, to write many long letters, to keep a diary, to go in a great deal for music and authorship. Especially the tendency of rhyming … is usually very conspicuous. … His pressure of activity causes the patient to change about his furniture, to visit distant acquaintances, to take himself up with all possible things and circumstances, which formerly he never thought about (

1, pp. 57–58).

The requirement of increased activity or energy during a manic/hypomanic episode in DSM-5 is consistent with Kraepelin’s observations, but the impact of using DSM-5 criteria on prevalence and treatment outcome is unclear. To assess the diagnostic validity of the DSM-5 criteria for mania/hypomania, Zarate and colleagues (

2) analyzed DSM-IV data obtained at the time of the initial visit and follow-up visits of subjects participating in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder study (STEP-BD) to estimate the point prevalence of DSM-5 mania/hypomania. In DSM-IV, the A criterion for a manic episode only required “a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, lasting at least 1 week.” DSM-5 brings substantial changes to the A criterion for mania, which now requires in addition the presence of “abnormally and persistently increased goal-directed activity or energy”; moreover, these symptoms must not only last at least 1 week, they must also be “present most of the day, nearly every day.”

Using data from the 4,360 patients enrolled in the STEP-BD study, Zarate et al. compared prevalence, clinical characteristics, validators, and clinical outcomes in the 310 subjects who presented with mania/hypomania at the time of study entry. The authors hypothesized that when the new DSM-5 criterion of increased activity/energy was added as a core requirement, the prevalence of mania/hypomania would decrease—and it did so, by 48%. Despite this change in prevalence, only minor differences were noted in clinical and concurrent validators, and no changes were observed in longitudinal outcomes between those who did and those who did not meet the DSM-5 criteria. This appears to challenge the validity of differentiating these two groups of patients. From a very pragmatic clinical perspective, there is the possibility that the medical management of these new subtypes may not be sufficiently informed.

We appreciate the analyses conducted by Zarate and colleagues and share their desire for greater diagnostic accuracy, which was in fact the goal of including increased energy as a required criterion for diagnosis of mania/hypomania. However, it should be noted that Zarate and colleagues’ analysis of STEP-BD data was based on the manic/hypomanic symptoms reported on the Clinical Monitoring Form, which was developed to gather clinical information regarding mania/hypomania and depression, such as symptom severity, and to assess treatment response. Although questions regarding symptom severity were focused on the DSM-IV criteria for depression and manic/hypomanic episodes, the instrument was primarily intended to help clinicians tie clinical management decisions to an identified current clinical status. The Clinical Monitoring Form thus rated symptoms of mania and depression over the past 7–10 days rather than conforming to the time frame DSM-IV specifies for episode diagnoses (

3). It is possible that the primary findings from the analyses conducted in the Zarate et al. study are not generalizable to lifetime prevalence. All subjects entering STEP-BD had a history of prior episodes of abnormal mood elevation, but the sample analyzed by Zarate and colleagues included only those with a current episode of mania/hypomania at the time of their intake visit.

Although increased energy has long been recognized as a common feature of mania/hypomania, the question is why DSM-5 adopted the criterion “and” increased energy instead of “or” increased energy. Angst and colleagues (

4) reported that increased energy or activity alone had equal validity for diagnosing bipolar disorders, and it should be noted that benefit derived from requiring the additional criteria probably increases specificity at the expense of sensitivity (

5). We agree that increased energy and “busyness” is a common characteristic of mania/hypomania, but we do not believe the data indicate that adding an extra requirement optimizes the balance of sensitivity and specificity from a clinical perspective.

Pragmatic Considerations

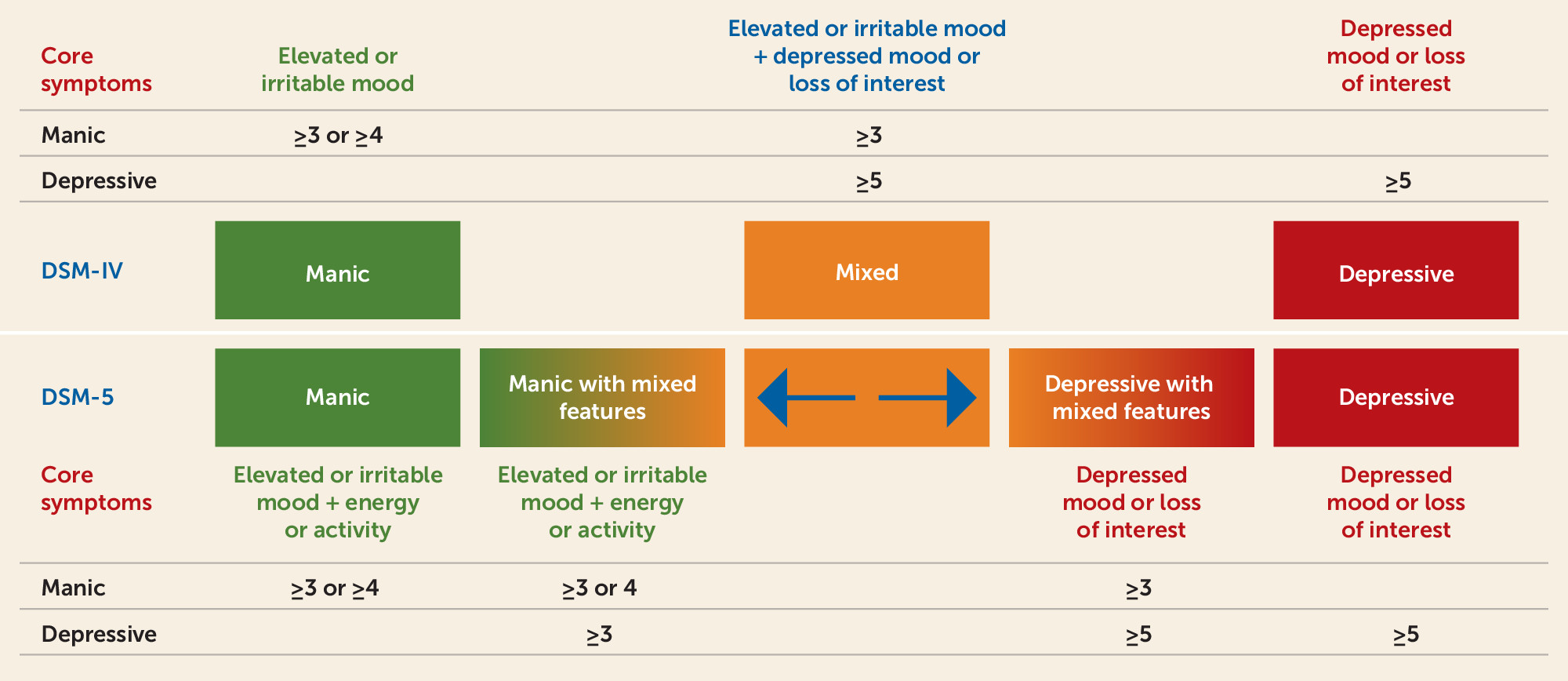

From the perspective of the practicing clinician, the changes to DSM-5 substantially increase the complexity associated with the diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder, but no longer require the clinician to ignore clinically significant symptoms that may be present. It should be noted that Kraepelin conceptualized manic-depression as a single illness with a continuum of episodic presentations including admixtures of symptoms we now consider of opposing polarity. DSM-5 represents an advance with promise to improve treatment outcomes, because it enables clinicians to diagnose mood episodes and specify the presence of symptoms inconsistent with pure episodes, for example, major depressive episodes with or without mixed features and manic/hypomanic episodes with or without mixed features (

Figure 1).

The analysis conducted by Zarate et al. suggests that those who did not meet the DSM-5 criteria for mania/hypomania were likely to fall into the category of major depressive disorder, by virtue of having major depressive episodes with mixed features (

2). In order to be diagnosed as having major depressive episode with mixed features, patients must exhibit at least three symptoms of mania or hypomania as well as at least five symptoms of a major depressive episode (

Figure 1). Patients presenting with manic episode with mixed features must exhibit at least three (euphoria) or four (dysphoria) of seven symptoms of mania and at least three symptoms of depression (

Figure 1). Although mania with mixed features has been shown to respond to treatment with mood stabilizers and antipsychotics, there is less consensus regarding the clinical management of major depressive episodes with mixed features, especially when associated with major depressive disorder. It is important to understand the extent to which adverse outcomes, treatment-emergent induction, and treatment-refractory presentations may be associated with use of traditional antidepressants in the latter group. Clearly, there is an urgent unmet need to conduct clinical trials in patients with major depressive episodes with mixed features who have never had prior episodes of hypomania or mania. Before such evidence becomes available, clinicians should discuss the potential risk of future hypomania/mania with all depressed patients and monitor closely for the emergence of manic/hypomanic symptoms when prescribing traditional antidepressants for patients with mixed features.