Tardive dyskinesia is an often persistent and disabling condition associated with chronic exposure to dopamine receptor blockers, including antipsychotic and antiemetic agents (

1–

3). Hallmark symptoms include involuntary movements of the face, trunk, and/or extremities (

4). Although second-generation, or atypical, antipsychotics were initially anticipated to confer a lower risk for tardive dyskinesia, current evidence suggests that both first- and second-generation antipsychotics are associated with a meaningful risk for tardive dyskinesia (

5–

8). It is estimated that approximately 20%–30% of patients with chronic exposure to antipsychotics develop tardive dyskinesia (

1,

7). The number of cases appears to be increasing along with the widespread use of atypical antipsychotics, including for indications beyond psychosis (

2).

One approach to managing tardive dyskinesia is to discontinue antipsychotic treatment or reduce the dosage, but these options are not always feasible, because withdrawal can exacerbate tardive dyskinesia symptoms or have a negative impact on psychiatric status (

1,

8). Moreover, tardive dyskinesia symptoms often persist even after discontinuation or dosage reduction (

1,

3). Conversely, increasing the dosage may initially reduce (or “mask”) involuntary movements but ultimately worsen the underlying tardive dyskinesia, making management more difficult (

1,

7).

No medications are currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia, although various drugs have been studied and used off-label (

4); however, evidence for these therapies is limited (

2,

8). One class of drugs that has shown promise in treating movement disorders are the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors. By modulating the presynaptic packaging and release of dopamine into the synapse, these drugs may offset the movement-related side effects of antipsychotics and other dopamine receptor blocking agents (

9,

10). The VMAT2 inhibitor tetrabenazine is approved for treating the involuntary movements (chorea) of Huntington’s disease and has shown some favorable effects in patients with other hyperkinetic movement disorders (e.g., tardive dystonia, Tourette’s syndrome tics) (

11). This body of research, along with the reported short-term effects of tetrabenazine in tardive dyskinesia (

2), has helped renew interest in VMAT2 inhibitors in the treatment of tardive dyskinesia and other movement disorders.

Valbenazine (NBI-98854) is a novel and highly selective VMAT2 inhibitor being developed for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. Valbenazine has a favorable pharmacokinetic profile with once-daily dosing. In a phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, valbenazine (escalated from 25 mg/day to a maximum of 75 mg/day) was shown to significantly reduce tardive dyskinesia severity, as assessed by blinded central Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (

12) ratings of videorecorded examinations and on investigator- and patient-rated global assessments (

13). Here, we provide results from a phase 3 trial (KINECT 3) that was conducted to further evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of valbenazine at fixed dosages in adults with tardive dyskinesia.

Method

Study Design

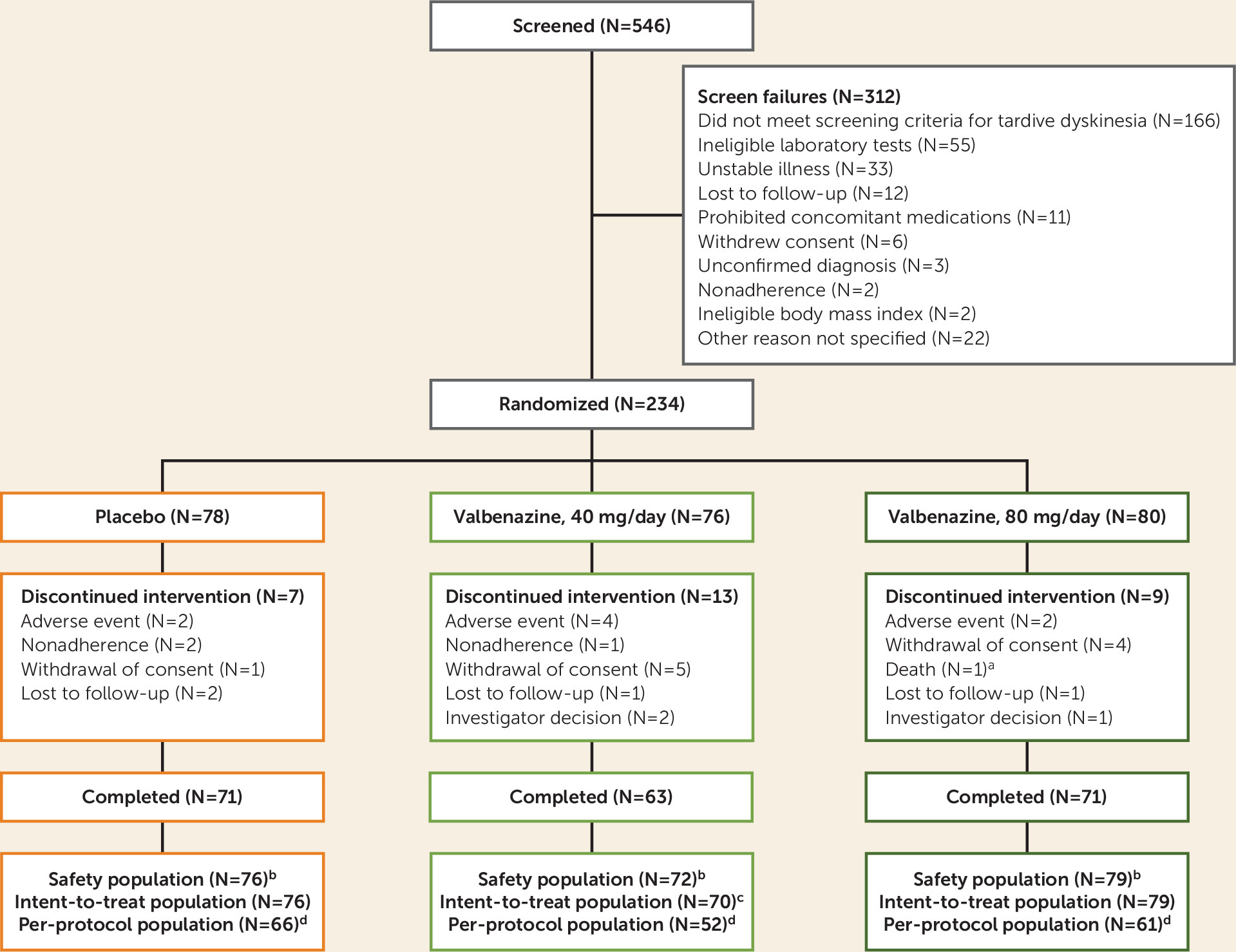

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, fixed-dose study in which eligible patients received 6 weeks of once-daily valbenazine (40 mg or 80 mg) or placebo (see Figure S1 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article). Participants subsequently entered a 42-week extension period of valbenazine at 40 or 80 mg/day, the results of which will be reported separately.

The 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled period of the study was conducted from October 2014 to September 2015 at 63 centers in North America (59 in the United States, two in Canada, and two in Puerto Rico). The study adhered to International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, U.S. Code of Federal Regulations standards, FDA guidelines, and the Health Canada Guidance for Clinical Trial Sponsors. Only individuals assessed as having the capacity to provide consent (using the University of California, San Diego Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent) (

14) were allowed to participate in the study. For each participating center, the study protocol was approved by an institutional review board.

Participants

Participants had to be medically stable, 18–85 years of age, and meet the following eligibility requirements: diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or mood disorder according to DSM-IV criteria for ≥3 months prior to screening; DSM diagnosis of dopamine receptor blocker–induced tardive dyskinesia for ≥3 months prior to screening; and moderate or severe tardive dyskinesia based on qualitative assessment of screening videos by external reviewers.

Participants were required to have stable psychiatric status and were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: a total score ≥50 on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (all participants); a total score ≥70 on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (

15) or a total score ≥10 on the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (

http://www.ucalgary.ca/cdss/) (participants with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder); a total score ≥10 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (

16) or a total score >13 on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (

17) (participants with mood disorder). Other key exclusion criteria were any clinically significant unstable medical condition, any comorbid involuntary movement disorder more prominent than tardive dyskinesia (e.g., parkinsonism, akathisia, truncal dystonia), a score ≥3 on two or more items of the Simpson-Angus Scale (

18), a history of neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and a significant risk of suicidal or violent behavior.

Randomization, Blinding, and Concomitant Medication Use

An interactive web response system was used to randomly assign participants in a 1:1:1 ratio to placebo, valbenazine at 40 mg/day, or valbenazine at 80 mg/day. All participants, investigators, study site personnel, central AIMS video raters, and the study sponsor were blind to treatment assignment. (Additional blinding methods are described in the Supplementary Methods section of the online data supplement.)

Investigators could reduce a participant’s dosage once during the study for tolerability. Dosage reduction was handled in a blinded fashion as follows: participants receiving placebo or valbenazine at 40 mg/day received a new study drug kit but remained at their current dosage; those receiving valbenazine at 80 mg/day thereafter received 40 mg/day kits. Any participant unable to tolerate the new “reduced” dosage was discontinued from the study.

Concomitant use of medications for the management of psychiatric and medical conditions was allowed. Participants were required to be on a stable treatment regimen for ≥30 days before baseline, and changes were discouraged during the study. Participants taking prohibited medications (e.g., strong CYP3A4 inducers, dopamine agonists and precursors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, stimulants, VMAT2 inhibitors) were required to complete a 30-day washout prior to screening.

Efficacy Endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline to week 6 in the AIMS dyskinesia score (the sum of items 1–7) for the valbenazine 80 mg/day group compared with the placebo group. Each participant’s AIMS examination was videorecorded at all study visits. Videos were reviewed and scored by a pair of expert central AIMS video raters (neurologists specializing in movement disorders) who were blind to treatment and study visit sequence. The central AIMS video rater pair provided consensus scores of 0–4 for AIMS items 1–7 for each visit (baseline and weeks 2, 4, and 6). The key secondary endpoint was the Clinical Global Impression of Change–Tardive Dyskinesia (CGI-TD) score, which site investigators used to rate overall change in tardive dyskinesia from baseline at week 6. CGI-TD scores range from 1 (“very much improved”) to 7 (“very much worse”). (Additional assessments are presented in Table S1 in the online data supplement.)

Safety Assessments

Treatment-emergent adverse events were defined as untoward events that occurred or worsened in severity after the first dose of study drug. Other safety assessments included vital signs, physical examinations, ECG, laboratory tests, the Simpson-Angus Scale, and the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (

19). The PANSS and the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia were used to monitor psychiatric status in participants with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. The YMRS and MADRS were administered to participants with mood disorders. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) (

20) was used to monitor emergence of suicidal ideation or behavior in all participants.

Statistical Analysis

The estimation of sample size is presented in the Supplementary Methods section of the online data supplement. Three analysis sets were defined for data evaluation. The safety population included all participants who underwent randomized assignment to treatment, received at least one dose of study drug, and had at least one postbaseline safety assessment. The intent-to-treat population included all participants in the safety population who also had at least one postbaseline AIMS assessment. The per-protocol population included all participants in the intent-to-treat population who had an AIMS score and a detectable plasma level of valbenazine at week 6 (if assigned to valbenazine) and no important efficacy-related protocol deviations. Analyses conducted in the per-protocol population were considered supportive and are reported here for change from baseline at week 6 in AIMS dyskinesia score and for CGI-TD score at week 6.

The primary and key secondary endpoints were analyzed in the intent-to-treat population using a mixed-effects model for repeated measures that included baseline AIMS dyskinesia score as a covariate; treatment group, psychiatric diagnosis (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, mood disorder), and study visit as fixed effects; subject as random effect; and treatment-by-week and baseline score-by-week (AIMS dyskinesia score only) interaction terms. The mixed-effects model for repeated measures accounted for dependence within subjects across study visits throughout the trial. Change scores on the AIMS dyskinesia scale are reported as least square means. Treatment effect sizes were calculated based on Cohen’s d.

A fixed-sequence testing procedure was used to control the family-wise error rate for the primary and key secondary endpoints, as well as for two valbenazine treatment group comparisons to placebo (each performed at a nominal alpha of 0.05). The first step determined the statistical significance of valbenazine at 80 mg/day compared with placebo for the primary efficacy endpoint (change from baseline in AIMS dyskinesia score at week 6). If that comparison was significant, the statistical significance of valbenazine at 80 mg/day compared with placebo was tested for the key secondary endpoint (CGI-TD score at week 6). If both analyses indicated a significant treatment effect, the same order of testing was conducted for valbenazine at 40 mg/day compared with placebo. For any test result in this sequence to be considered statistically significant, all previous results in the list were required to have met the 0.05 significance threshold.

A supportive analysis was performed based on AIMS response (a reduction of ≥50% from baseline in AIMS dyskinesia score), analyzed at each postbaseline visit. Comparisons between the valbenazine and placebo groups were performed using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test with the primary psychiatric diagnosis as a stratification variable. An exploratory analysis based on the full range of percent improvements in AIMS dyskinesia score (10%–90%) was also conducted. Baseline characteristics and safety outcomes were analyzed descriptively.

Discussion

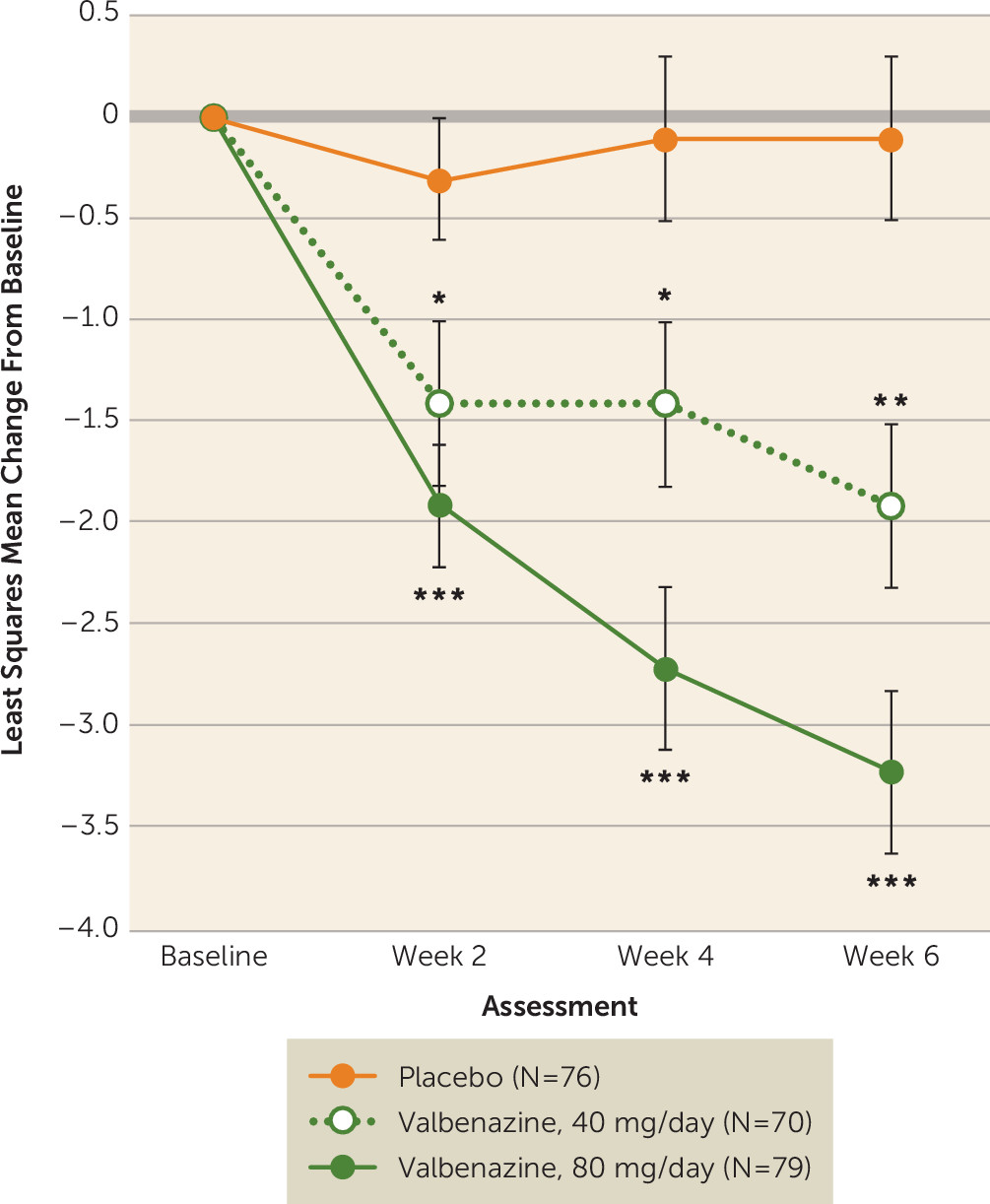

This is the first phase 3 trial of valbenazine, a novel VMAT2 inhibitor in clinical development for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia in adults. In showing a significant difference between valbenazine at 80 mg/day and placebo in AIMS dyskinesia score change at week 6, this study met the predefined primary endpoint and confirmed findings from the earlier phase 2 trial (KINECT 2; NCT01733121) (

13).

Treatment with valbenazine at 40 mg/day also showed improvement compared with placebo in AIMS dyskinesia score change at week 6, but based on the prespecified fixed-sequence testing procedure, the reduction in AIMS dyskinesia score at the 40-mg dosage was not considered statistically significant. However, clinical implications of the results from both valbenazine dosage groups warrant further exploration, particularly since clear improvements in AIMS dyskinesia score were observed with both dosages within 2 weeks of treatment (

Figure 2). While all participants had a qualitative assessment of moderate or severe tardive dyskinesia at screening, AIMS dyskinesia scores at baseline (mean=10.0; range=0–20) indicate that dyskinesia severity can be variable (see Figure S3 in the

online data supplement).

The supportive per-protocol analyses implemented in this study included only participants with a detectable plasma level of valbenazine (if assigned to valbenazine treatment) at the week 6 visit and excluded those (17/149, 11.4%) with undetectable levels. In participants with detectable levels, both dosages of valbenazine demonstrated a significant benefit over placebo in AIMS dyskinesia score change and CGI-TD score at week 6. Such results underscore the importance of including prespecified, objective measures to quantify the impact of nonadherence in clinical trials.

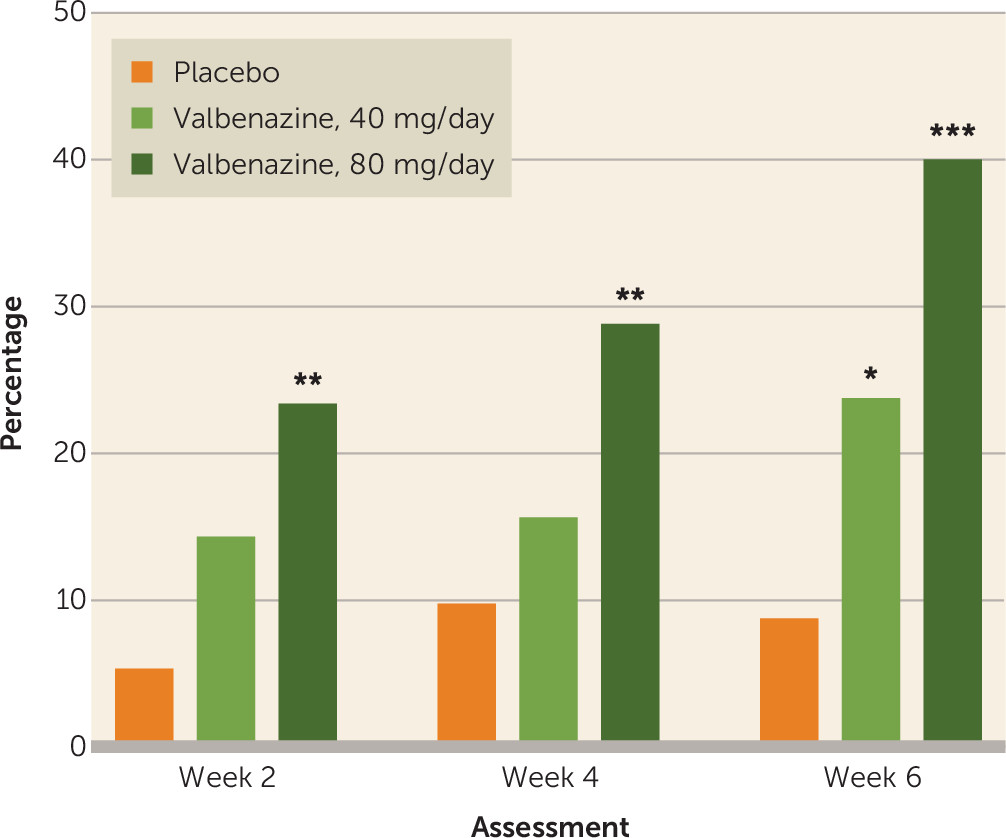

A validated minimal clinically important difference has not been established for change in AIMS dyskinesia score, partly because of the lack of comparability between multiple versions of the AIMS used in previous studies in tardive dyskinesia. In this trial, however, the percentage of participants who had an improvement of ≥50% from baseline in AIMS dyskinesia score was significantly higher with valbenazine (80 and 40 mg/day compared with placebo) at week 6, and significant outcomes were observed at all scheduled study visits for the 80 mg/day dosage (

Figure 3). The threshold definition for AIMS response in this study was relatively high; other studies have used less rigorous criteria to define treatment response (e.g., reductions ≥25% or ≥30% from baseline in AIMS dyskinesia score) (

21,

22). Individual patients may of course have lesser (or greater) reductions of dyskinesia that could also be considered a “response,” and a full range of improvements was seen in the present study (see Figure S2 in the

online data supplement). Clinical relevance also may be characterized by assessing global improvements in tardive dyskinesia, a method that was employed in the earlier phase 2 study and the current phase 3 study (

13,

23). Ease of use in clinical settings is one potential benefit of single-item measures such as the CGI-TD and the Patient Global Impression of Change, but these instruments may not be sufficiently sensitive for assessing changes in tardive dyskinesia symptoms, especially as some patients may have limited awareness and insight regarding their movements (

24).

Valbenazine appeared to be well tolerated in this study population with underlying schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or a mood disorder. Only two participants assigned to treatment with valbenazine at 80 mg/day required a dosage reduction (whereas three participants in the placebo group underwent dummy dosage reductions), emphasizing the overall tolerability of valbenazine. Reported treatment-emergent adverse events were consistent with those observed in the earlier phase 2 trial (

13), and no unexpected safety signals were detected during this study. Somnolence (5.1% of participants in the 80 mg/day and 5.6% in the 40 mg/day group) and dry mouth (6.9% in the 40 mg/day group) were the only treatment-emergent adverse events reported in ≥5% of participants in either valbenazine group. Moreover, discontinuations due to treatment-emergent adverse events were comparable between valbenazine (80 mg/day, 6.3%; 40 mg/day, 5.6%) and placebo (5.3%).

One method for estimating the clinical relevance of trial data is to calculate the number needed to treat (NNT) for a desirable outcome and weigh it against the number needed to harm (NNH) for an unwanted outcome. Both NNT and NNH are derived from the inverse of the rate difference for the outcome of interest. For example, AIMS response rates at week 6 for valbenazine at 80 mg/day and placebo (40.0% and 8.7%, respectively) translate into an NNT of 4 (1/[0.40–0.087]=3.2, rounded up to 4), suggesting that four patients with tardive dyskinesia would need to receive valbenazine 80 mg/day in order to demonstrate a robust treatment response in at least one additional patient (

25). In contrast, the incidence of any treatment-emergent adverse event for valbenazine at 80 mg/day and placebo (50.6% and 43.4%, respectively) yields an NNH of 13, indicating that 13 patients would need to receive valbenazine at 80 mg/day before one additional patient experiences an adverse event. For valbenazine at 40 mg/day versus placebo, the NNT for AIMS response is 7 and the NNH for any treatment-emergent adverse event is −32. The negative value of this NNH reflects the lower incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events for valbenazine at 40 mg/day relative to placebo (40.3% and 43.4%, respectively) and suggests that no appreciable risk of decreased tolerability was observed with the 40 mg/day dosage. Overall, the NNT/NNH comparisons for both dosages suggest that the benefits of valbenazine may outweigh the safety risks.

In this study population, safety assessments of psychiatric condition and suicidality were conducted at each visit. Notably, there was no apparent increase in suicidality with valbenazine, and mean scores on psychiatric scales assessing symptoms of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (PANSS), depression (Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia, MADRS), or bipolar disorder (YMRS) remained stable during valbenazine treatment.

The double-blind, placebo-controlled period of this trial was of relatively short duration, potentially limiting our ability to evaluate the full impact of valbenazine on the durability of tardive dyskinesia response. No conclusions can be drawn regarding the long-term efficacy, safety, or tolerability of the drug from this period alone; nor is it possible to discern whether masking may have contributed to the improvements observed in this study. However, the 6-week period reported here was followed by a 42-week extension period. Once available, results from the extension period, along with findings from an ongoing 52-week study (KINECT 4; NCT02405091) and an up-to-72-week rollover study (NCT02736955), will provide information about the long-term effects of this medication in adults with tardive dyskinesia.

The results from these trials are also expected to serve as a substantial and expansive database that can be used to learn more about the phenomenology and course of tardive dyskinesia, the types of patients who might best respond to medication, baseline characteristics and adverse event profiles in treatment responders compared with nonresponders, strategies for maintenance therapy, the impact of treatment on daily functioning, and the potential for clinical remission. Finally, although valbenazine appeared to have dose-related effects on efficacy, the planned statistical analyses were not designed to test for differences between the 40 and 80 mg/day dosages. Identifying the benefits and risks of different valbenazine dosages in patients with tardive dyskinesia is a question for future research.

In conclusion, once-daily treatment with valbenazine at 80 mg/day significantly improved tardive dyskinesia compared with placebo in a population of patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or a mood disorder. Both valbenazine dosages were generally well tolerated, even as participants were taking a wide range of concomitant medications. Psychiatric status in these patients, based on reported rates of adverse events and specific psychiatric scales, remained stable. The findings from this trial suggest that valbenazine may be an effective treatment option for patients with tardive dyskinesia.