Clozapine is the most effective antipsychotic treatment for treatment-resistant schizophrenia (

1) and is recommended for such patients in Danish and several other national guidelines (

2–

4). However, clozapine is underused in most countries, probably because of the fear of severe side effects and the inconvenience of therapeutic blood monitoring (

5). Consequently, alternative treatment strategies, such as switching medications or augmenting clozapine with other antipsychotics, are often applied (

6). Antipsychotic polypharmacy is common, despite the lack of evidence for its efficacy (

7).

An excess rate of early mortality in schizophrenia has been demonstrated in several studies, with elevations in rates of both natural and unnatural causes of death (

8,

9). Mortality in association with antipsychotic treatment—especially clozapine—has been studied extensively in recent decades. The FIN11 study found a significantly lower mortality rate among users of clozapine than among users of any other antipsychotic drugs (

10). Several studies similarly concluded that clozapine was associated with a lower all-cause mortality rate compared with no antipsychotics or first-generation antipsychotics (

11), no lifetime clozapine use (

12), and past or recent clozapine use (

13). Other studies did not find significant differences in all-cause mortality between clozapine and haloperidol (

14) or other antipsychotics (

15). Clozapine has particularly been found to be associated with a lower risk of suicide (

10,

11,

14) and suicide attempts (

14,

16). However, concern about a potentially higher risk of suicide following clozapine discontinuation has been raised (

17).

These studies are comparable in their use of an observational design, which is required because randomized controlled trials cannot address the issue of mortality in association with clozapine owing to the unfeasibly large sample size and long follow-up time that would be required to detect differences in a relatively rare outcome. However, observational studies differ in length of follow-up, model adjustment, and exposure definition used. Moreover, most previous observational studies used different comparison groups, including individuals with schizophrenia or schizophrenia spectrum disorders not eligible for clozapine, leading to the problem of confounding by indication: it was not possible to distinguish whether the effect on mortality was due to clozapine treatment specifically or to treatment-resistant schizophrenia in general. One exception is the study by Stroup and colleagues (

15), which restricted the study cohort to individuals with treatment-resistant illness and found no significant difference in all-cause mortality and self-injurious behavior when comparing clozapine users with individuals using other antipsychotics (

15). Even though a potentially adequate comparison group was selected, follow-up was restricted to 1 year, and mortality after clozapine discontinuation was not studied. Another study examined mortality in current or past clozapine users but did not include individuals who were eligible but not receiving clozapine (

13).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate rates of all-cause (and cause-specific) mortality and self-harm in association with clozapine treatment and alternative antipsychotic treatment strategies among individuals with schizophrenia meeting criteria for treatment resistance.

Method

Data Sources

We extracted information on medication from the Danish National Prescription Registry, where all outpatient drug prescriptions have been registered since 1995 (

18). We obtained information on admission dates and diagnoses (ICD versions 8 and 10) from the Danish National Patient Registry (

19) and the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register (

20). We obtained information on sex, date of birth, vital status, and nationality and parents' personal identification numbers from the Danish Civil Registration System (

21). Information on causes of death was obtained from the Causes of Death Register; information was available until Dec. 31, 2011 (

22). The unique personal identification number was used to link individual data across the national registration systems, including registers holding sociodemographic information (

21).

Study Cohort

We conducted a population-based cohort study. The cohort comprised all individuals born in Denmark after Jan. 1, 1955, with a first diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD 8: 295.x9, excluding 295.79; ICD-10: F20) at age 18 or older and after Jan. 1, 1996, and fulfilling criteria for treatment resistance before June 1, 2013. To define the cohort and start of follow-up (baseline), we used a register-based definition of treatment-resistant schizophrenia based on either of the following two criteria: 1) clozapine prescription filled at a pharmacy or 2) psychiatric hospital admission within 18 months during continued treatment with antipsychotics after at least two periods of monotherapy with different antipsychotics, each lasting at least 6 weeks. The definition has been applied and described more fully elsewhere (

23).

Mortality and Self-Harm

We studied all-cause and cause-specific mortality as well as the first recorded episode of self-harm after the patient met one of the criteria for treatment resistance. All-cause mortality was defined by using the recorded date of death retrieved from the Danish Civil Registration System, where vital status is continuously updated. We assessed causes of death from the Causes of Death Register: suicide, death from diseases and medical conditions, and death from other external causes, as classified in a previous study (

24). Self-harm was defined as the first registered episode of self-harm after the criteria for treatment resistance were met. Self-harm events included suicide attempts as well as self-harm behaviors such as cutting and poisoning (excluding use of food, alcohol, and mild analgesics) (

25–

28).

Clozapine and Other Antipsychotic Treatment

The primary exposure was defined as time-varying treatment, classifying individual follow-up time into periods of clozapine treatment and no clozapine treatment. This was defined from prescription data as described in Table S1 in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article. “No clozapine treatment” was further classified into nonclozapine antipsychotic treatment and no antipsychotic treatment so that the former could serve as an active comparator group.

Secondary exposure measures were also defined. First, to account for periods of concomitant antipsychotic treatment, treatment status was classified according to the following subcategories: clozapine monotherapy (reference), clozapine with other antipsychotics, nonclozapine antipsychotic polypharmacy, nonclozapine antipsychotic monotherapy, and no antipsychotic treatment. Next, to study the timing of all-cause mortality in relation to clozapine, the time-varying treatment was classified as periods of past, no, and current clozapine treatment.

Potential Confounders

We adjusted for sex and previous episodes of self-harm as well as the following time-dependent factors: age, calendar year, comorbid substance abuse, comorbid somatic disorders (Charlson index score >0) (

29), comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (other schizophrenia spectrum disorder, singular or recurrent depression, personality disorder), living in the capital area, and cumulative clozapine treatment (0, 0–1, 1–3, ≥3 years).

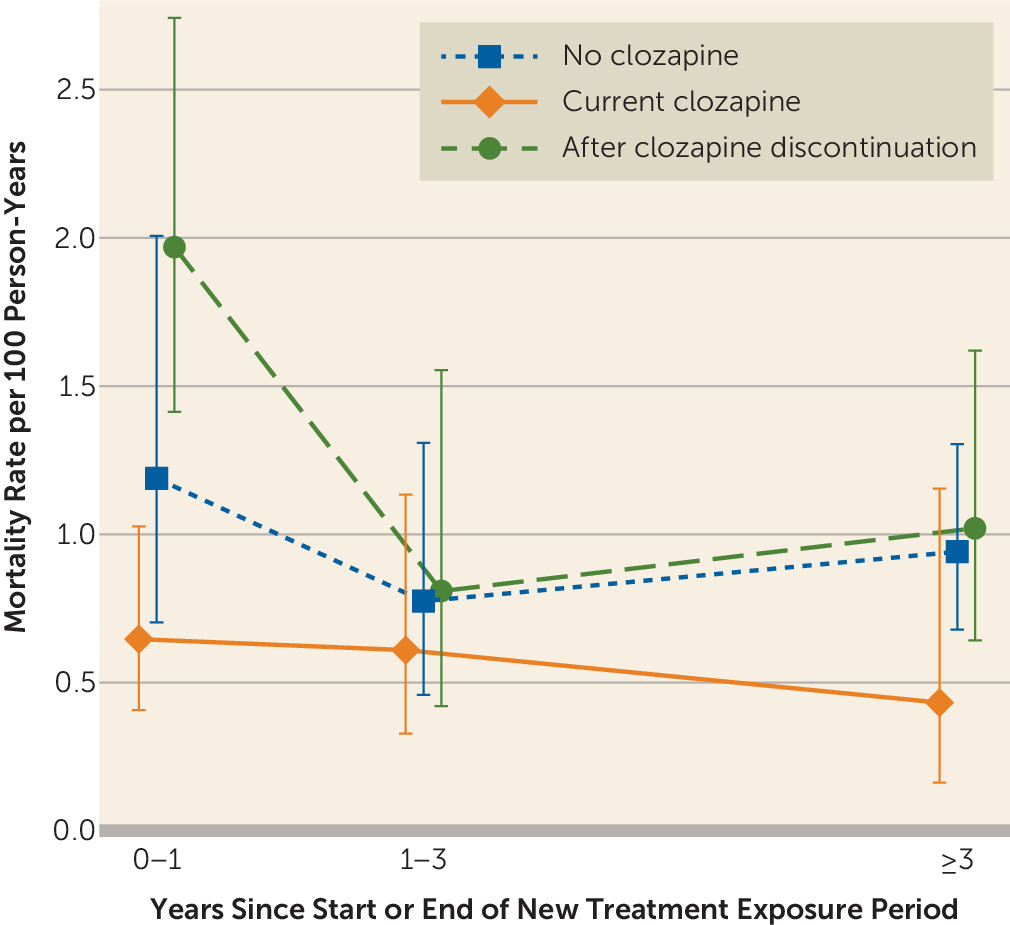

Data Analysis

We performed crude and adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression and analyzed time to death as well as time to the first recorded episode of self-harm in separate models, where individuals were followed from the date of meeting criterion 1 or 2 for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, whichever came first. Individuals were censored at emigration from Denmark or end of follow-up (June 1, 2013). Clozapine treatment (the recommended treatment in treatment-resistant schizophrenia) was used as the reference, allowing for direct presentation of hazard ratios for several comparisons, including different antipsychotic treatment strategies. This implies, for instance, that a hazard ratio above 1 favors clozapine, as it has a lower event rate. Estimates for the opposite comparison can easily be obtained by inversion of both the hazard ratio and confidence limits. For all-cause mortality, we additionally studied the timing of death by comparing rates after clozapine discontinuation (designated as past clozapine treatment) and rates during nonclozapine treatment with rates during current clozapine treatment. For this analysis, we reset the time period at the beginning or end of a clozapine treatment period. Because individuals could contribute to several treatment periods, we used robust standard errors to account for intraindividual correlation. Hazard ratios were presented for models splitting follow-up into the following time intervals: 0–1, 1–3 and ≥3 years to assess the timing of death after clozapine discontinuation. For cause-specific death, analyses were conducted for crude and partly adjusted models and with further adjustment for psychiatric hospitalization in the previous year. Individuals were censored at death from other causes, emigration from Denmark, or last available information on cause of death from the Causes of Death Register (Dec. 31, 2011).

The proportional hazards assumption for the Cox regression models was evaluated from diagnostic plots for baseline variables. All estimates are accompanied by 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All analyses were conducted in Stata version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex.).

Sensitivity analyses.

First we repeated the analyses with exclusion of inpatient stays at psychiatric hospitals lasting longer than 1 month to account for the fact that we do not have information on medication during hospitalization. Next we conducted an analysis that censored at first change in treatment status (i.e., following individuals only until their first discontinuation of initial clozapine or other antipsychotic treatment). The main analyses were repeated with long-acting injectable antipsychotics in a separate category, adjusted for a smaller set of potential confounders because of fewer events in one category. In another approach—a so-called initial-treatment approach—treatment status was obtained at baseline and was carried forward during the entire follow-up period. Analyses were conducted on the basis of multivariable models and on the basis of a propensity score-matched cohort adjusted for a large set of potential confounders (Table S3, online data supplement). A description of the method can be found in the online supplementary material.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that clozapine treatment in treatment-resistant schizophrenia was associated with a substantially lower rate of all-cause mortality compared with no antipsychotic treatment, and there was an increase in mortality after clozapine discontinuation. Moreover, we found a significantly lower rate of self-harm during clozapine treatment compared with nonclozapine antipsychotic treatment in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

Our finding of a lower mortality rate in association with clozapine is in line with findings of previous studies (

10–

12). Our results indicate a potential protective effect of clozapine when compared with other antipsychotics, particularly nonclozapine antipsychotic monotherapy in treatment-resistant schizophrenia, but the results were not statistically significant. Whereas some studies have not been able to detect a significant protective effect of clozapine compared with other antipsychotics (

14,

15), other studies have demonstrated a significantly lower risk of overall death or suicide in clozapine users, even when compared with patients taking other second-generation antipsychotics (

10,

11). The estimated effects of current clozapine treatment compared with other antipsychotics in the present study were, although statistically nonsignificant, of a size fairly similar to the effect estimates of clozapine compared with perphenazine observed in the FIN11 study (

10).

Our finding of a significantly reduced rate of self-harm in clozapine users corroborates previous research (

14,

16). Unexpectedly, in the present study no significant effect was observed in adjusted analyses when clozapine was compared with no antipsychotic treatment, and the highest rate of self-harm was observed for nonclozapine antipsychotic polypharmacy. More evidence is needed to further explore whether treatment strategies using antipsychotics other than clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia might increase the risk of self-harm, even when compared with no antipsychotic use.

The study by Stroup and colleagues was likely closest in design to our study in that they also restricted the cohort to treatment-resistant schizophrenia, although they restricted the data to 1 year of follow-up (

15). Unlike their study, with no significant findings of reduced all-cause mortality and self-injurious behavior in clozapine users compared with other antipsychotic users, our study showed reduced rates of mortality and self-harm associated with clozapine treatment. Moreover, when we restricted outcomes to 1-year follow-up or the first change in treatment status, even larger effect sizes were observed than in analyses based on the entire follow-up period. Differences in findings between the studies might to some extent be explained by differences in exposure and outcome definitions used, unmeasured confounding, and different treatment settings.

In line with previous findings (

10,

13,

14), we found the largest effect size for suicide. In the present study, lower estimates for death caused by medical conditions during clozapine treatment also indicate a protective effect of clozapine. For analyses of cause-specific mortality, the number of events was small, and a potential statistically significant association could not be detected.

In the present study, we found that mortality was increased after discontinuation of clozapine treatment, with a significant excess mortality rate in the first year or even within 3 months after discontinuation. This finding is in line with previous reports (

13). This indicates that death after clozapine discontinuation, probably due to causes other than suicide, is a reason for concern (

17). We do not know whether the severity of disease (mental or somatic) caused the discontinuation or the other way around. One potential explanation is that clozapine, or at least its procurement from the pharmacy, is discontinued because of severe medical conditions related or unrelated to treatment with clozapine, also known as the “sick-stopper effect” (

30). Side effects and deaths have been reported as the most common reasons for discontinuation (

31). One study found that adverse drug reactions accounted for over half of clozapine discontinuations, with sedation being the clearly most common, followed by neutropenia and tachycardia (

32). In the present study, the number of deaths within the year following clozapine discontinuation was not sufficient to stratify analyses by different causes of death.

To our knowledge, the present study was the first to study mortality and self-harm across different treatment strategies in comparison with clozapine in a cohort of individuals with apparent treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Mortality rates were highest in periods of no antipsychotic treatment and significantly lower in periods of clozapine treatment. Rates of self-harm episodes were highest in periods of nonclozapine antipsychotic treatment and significantly lower in periods of clozapine treatment. Adjusted analyses with long-acting injectable antipsychotics in a separate category indicated that the increased rate of self-harm was particularly driven by other antipsychotics. The reductions in mortality or self-harm in comparisons of different antipsychotic treatment strategies with clozapine monotherapy did not reach statistical significance, probably due to fewer events in each exposure category.

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of the present study is the population-based, longitudinal study design linking several registers to gather information obtained at baseline as well as multiple times over a long follow-up period, up to 17 years. Information on all medication dispensed at all pharmacies in Denmark since 1995 was available, and the fact that the individual received the medication from the pharmacy largely indicates adherence. Another strength of the study is the restriction of the cohort to individuals meeting criteria for treatment resistance, which we consider the most appropriate approach for studying outcomes in relation to clozapine treatment, because all members of the cohort are considered to have an indication for clozapine. The study population used by Stroup and colleagues was also restricted to individuals with treatment-resistant schizophrenia (

15), but unlike them, we additionally used a time-varying treatment design, which enabled us to study the temporal and acute treatment effects over long-term follow-up, adjusting for several time-dependent factors associated with treatment and outcome. As a consequence of our chosen design, we assigned periods of no antipsychotic prescriptions to a separate exposure category.

Observational studies using registry data have some limitations. One limitation is the lack of information on antipsychotic medication status during hospitalization. However, we repeated analyses excluding periods of psychiatric hospitalization exceeding 1 month, resulting in similar estimates. Also, for a minor proportion of individuals, antipsychotic medication has been dispensed for up to 2 years free of charge through hospital pharmacies since 2008, resulting in no antipsychotic prescriptions being found for these individuals during this period. This might have biased the estimates, but with follow-up restricted to 2007, analyses resulted in similar estimated effect sizes.

The current study compared clozapine treatment with different overall treatment strategies but not with specific antipsychotic drugs, as was the case in the FIN-11 study (

10). However, the current study is to our knowledge the first study to compare clozapine with other antipsychotic monotherapy and long-acting injectable antipsychotics in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

The outcome in the present study termed “self-harm” included both suicide attempts (the majority) and self-harm without the intent of suicide. As we could not distinguish between the two and since underreporting of self-harm and suicide attempts from the Danish registers is a limitation (

28), it is possible that clozapine does not have similar effects on the risk of self-harm (without intent of suicide) and the risk of suicide attempt.

Furthermore, the results could be biased due to uncontrolled confounding by such elements as symptom type and severity, nonantipsychotic comedication and psychotherapy, and the inability of the register-based design to distinguish between discontinuation of antipsychotic medication due to medication nonresponse, intolerance, and nonadherence. Similarly, the register-based definition of treatment resistance is not a perfect proxy because the registers available did not include information on treatment nonresponse, and our cohort might thus include some individuals who were intolerant rather than nonresponsive to treatment. Furthermore, we could not take into account the regular contact with the health care system due to clozapine blood monitoring, which could serve as a potential intermediate factor associated with decreased severity in clozapine initiators (

12). However, clozapine remained the treatment associated with the lowest rates of death and self-harm in sensitivity analyses compared with long-acting injectable antipsychotics, which similarly require regular contacts with the health care system. No significant differences were observed between long-acting injectable antipsychotics and other nonclozapine antipsychotics, corroborating the findings of a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (

33). Still, clozapine blood monitoring might, at least in part, explain the lower rate of deaths in the first year after clozapine initiation or reinitiation and the higher rate after clozapine discontinuation. Thus, this study explores the overall real-world effect of different antipsychotic treatments rather than exclusively the pharmacological effect of the drugs.

Finally, the design of time-varying treatment and confounders might introduce collider-stratification bias, i.e., bias due to conditioning on factors affected by both the prior status of the covariate as well as by the prior treatment status. However, alternative methods such as time-varying propensity scores or inverse probability weighting of marginal structural models may not improve results markedly (

34).

Conclusions

The results of the present study indicate that clozapine use is associated with a decreased mortality rate, in line with previous research (

10–

12). This was, however, only significant when clozapine treatment was compared with periods of no antipsychotic treatment, a situation probably largely explained by an excess mortality rate observed after clozapine discontinuation. Furthermore, the results of the present study suggest a protective effect of clozapine in the prevention of self-harm when compared with other antipsychotics, but no effect was found when clozapine treatment was compared with no use of antipsychotics. It remains unclear whether the protective effect of clozapine on self-harm in treatment-resistant schizophrenia could be partly explained by a potentially harmful effect of alternative treatment strategies with other antipsychotics or confounding by indication. Moreover, the extent to which the observed excess mortality rate after clozapine discontinuation is caused by side effects from recent clozapine exposure, unobserved factors, or clozapine discontinuation remains to be investigated. This study suggests that clozapine discontinuation needs more attention with thorough evaluation, care, and monitoring of the patient.