Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is characterized by distressing mood and behavioral symptoms during the luteal phase of the normal menstrual cycle that disappear within a few days after menses begin (

1,

2). No abnormalities of ovarian hormone levels have been consistently identified that distinguish women with PMDD from women who experience no mood or behavioral symptoms during the luteal phase (

3). Nonetheless, a critical role for ovarian steroids in the expression of PMDD symptoms is suggested by multiple findings. First, both ovariectomy and ovarian suppression induced by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists eliminate symptoms in the majority of women with PMDD (

4–

15). Second, re-exposure to physiologic doses of either estradiol or progesterone (but not placebo) for 4 weeks’ duration resulted in a recurrence of PMDD symptoms after 2–3 weeks of exposure in women with PMDD whose symptoms remitted after GnRH agonist treatment (controls who participated in an identical hormone manipulation study were not symptomatic) (

14). Finally, inhibition of the luteal phase increase in the progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone with dutasteride, a 5α-reductase inhibitor, mitigated symptom emergence in PMDD (

16).

Reproductive steroids, therefore, appear to play a role in PMDD. What remains unclear is the nature of the ovarian steroid symptom trigger in PMDD. Evidence to date cannot disambiguate the effects of an acute change in the level of ovarian steroid (or metabolite) from those of continuous exposure to elevated levels of ovarian steroids. Preclinical studies suggest that the short-term exposure or withdrawal of progesterone could impact CNS function to induce affective symptoms in an otherwise vulnerable woman. Both increases and decreases in progesterone (and its neurosteroid metabolites) induce changes in the α4 subunit conformation of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) GABA

A receptor sufficient to produce anxiety-like behaviors (

17–

19). Alternatively, studies in rodents demonstrate that estradiol is proconvulsant and accelerates the acquisition of amygdalar-kindled seizures (

20,

21). Thus, ovarian steroids can modulate intrinsic neuronal excitation, lower thresholds for neuronal firing, and potentially impact the set points for certain behavioral states. If PMDD is associated with an abnormal infradian

zeitgeber, the expression of which depends on a critical threshold of exposure to ovarian steroids, then ovarian steroids could play a permissive role in the expression of abnormal neuronal activity within the affective circuits involved with PMDD, thus leading to symptom onset.

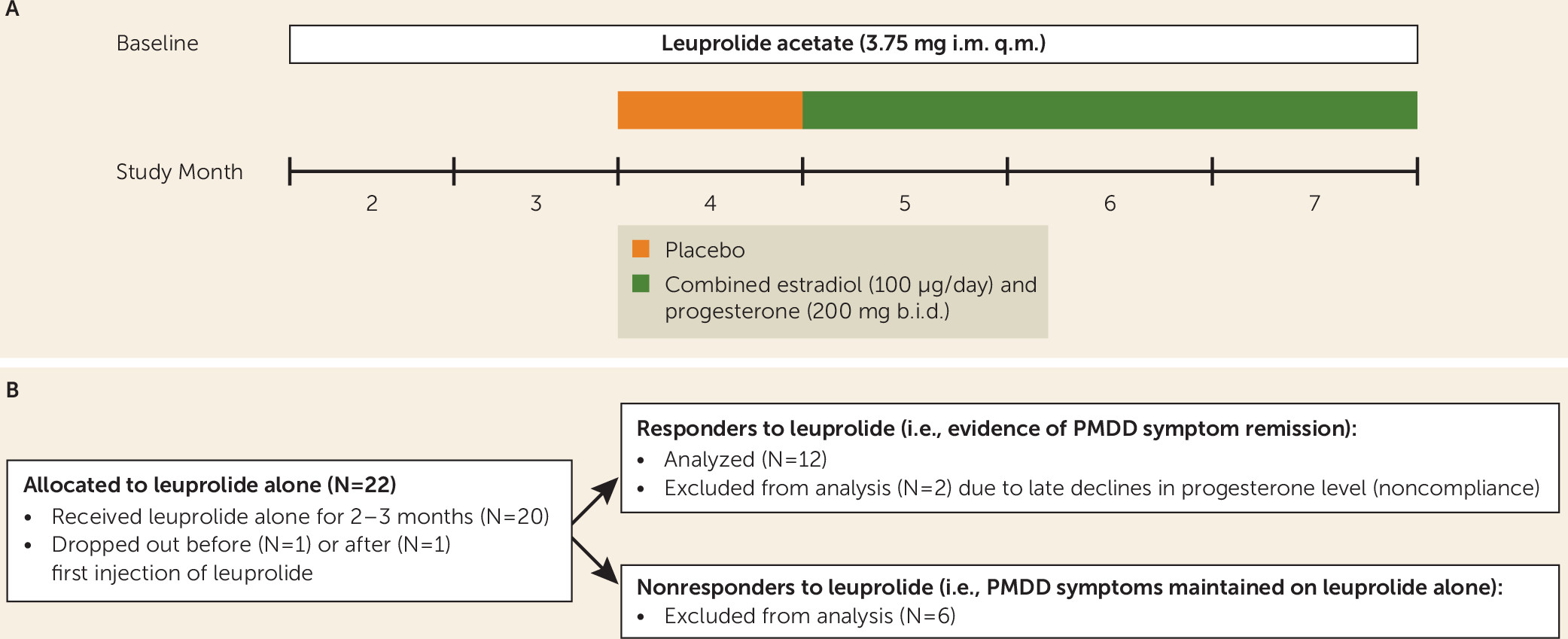

In this study, we attempted to define the kinetics of the ovarian steroid event relevant to triggering PMDD symptoms. We selected women with PMDD who responded to treatment with GnRH-agonist-induced ovarian suppression (i.e., whose PMDD symptoms remitted) and who then were exposed to 3 months of combined continuous estradiol and progesterone treatment. If the change in hormone level is critical, then we would expect the initial recurrence of PMDD symptoms in the first month of ovarian steroid exposure followed by a remission of PMDD symptoms once ovarian steroid levels were stable and maintained during months 2–3 of hormone treatment. Alternatively, if the ovarian steroid exposure above threshold levels is the key physiologic event to permit an infradian pacemaker to produce episodic cyclic symptoms during the luteal phase, then we would predict recurrent episodes of affective symptoms reminiscent of luteal-phase-related symptom cyclicity in the context of stable hormone levels during each of the three months of ovarian steroid exposures.

Discussion

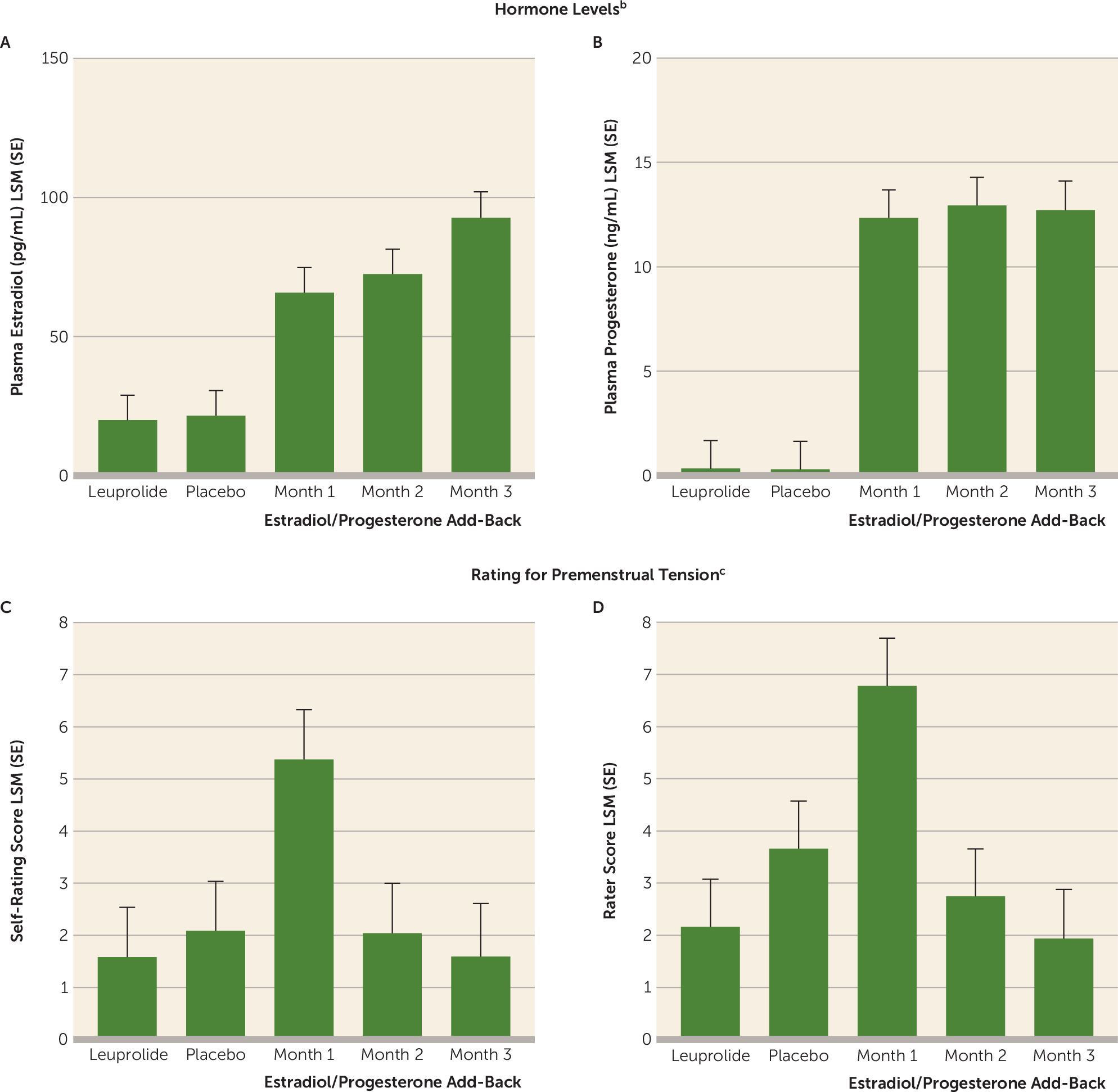

Apart from the ostensible linkage of PMDD symptoms to the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, the pathophysiologic role of ovarian steroids in this condition is suggested by observations that the short-term add-back of either estradiol or progesterone is sufficient to result in a recrudescence of symptoms in women with PMDD whose symptoms remitted during ovarian suppression (

14,

30). These observations left open the possibility that either dynamic hormonal events (i.e., changing ovarian hormone levels) during the menstrual cycle or the prolonged exposure to a threshold level of ovarian steroids was critical to the triggering of PMDD symptoms. In this study, we demonstrated that it was the changes in levels of estradiol and progesterone from low to high levels, and not the steady-state levels, that were associated with the onset of PMDD symptoms. We observed that compared with scores during the leuprolide-alone condition, several symptom rating scores significantly increased during the first month of ovarian steroid add-back but not during the second and third add-back months, when plasma levels of estradiol and progesterone were stable. Additionally, we observed no significant changes in symptoms during single-blind placebo add-back. Thus, our findings demonstrate that the change in level of ovarian steroids from low to high triggers the onset of a negative affective state in women with PMDD. Our results are consistent with several previous publications (

14,

30,

31) that have demonstrated an increase in symptoms during the initial ovarian steroid add-back in women whose PMDD responded to ovarian suppression. Interestingly, in the study by Segebladh and colleagues (

31), symptom recurrence was observed mainly upon add-back of both estradiol and progesterone, compared with low-dose estradiol alone, suggesting either that progesterone is a critical component of the symptom-triggering hormone event or that levels of ovarian steroids need to reach a specific threshold to trigger symptoms.

The appearance of symptoms in the women who experienced a recurrence of PMDD after the initial add-back was time-limited in all women, and symptoms remitted during the second and third months of hormone add-back, when plasma levels of estradiol and progesterone were relatively stable. Thus, our findings suggest that there is a “half-life” of the affective state that is triggered, following which it remits. The nature of the “switch-out,” or termination of the symptomatic state in PMDD, remains to be characterized.

The mechanism whereby a change in ovarian steroid levels induces a recurrence of symptoms in women with a history of PMDD is unclear. Steroid nuclear receptor signaling provides for a wide range of time- and rate-dependent regulatory mechanisms whereby a change in steroid level could impart differential cellular effects compared with those caused by steady-state levels (

32). For example, basic science studies suggest that the initial change (i.e., increase or decrease) in progesterone levels can induce alterations in GABA receptor subunit conformation and induce paradoxical anxiety-like behavior in rodents (

17–

19), and an initial pulse of progesterone activates transcriptional coregulators that differ from those seen after exposure to stable levels (

33). Indeed, the timing and pulsatility of a hormone signal may have physiologic relevance in the biology of several clinical phenomena, including the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, the stress response, growth and development, and circadian rhythms (

34–

43). Interestingly, symptoms recurred during the third month of add-back in two women with PMDD proximate to observed declines in progesterone levels. This anecdotal observation suggests that both acute increases and declines in ovarian steroids may trigger a transition from the asymptomatic to the symptomatic state, consistent with the observations of Gulinello and colleagues in rodents (

17–

19). Regardless of the mechanism underlying the steroid-induced recurrence of symptoms in PMDD, our findings provide a major clue to help decode the process by which clearly defined biological signals are, in susceptible individuals, translated into what is likely network-based affective dysregulation.

These findings have implications for the treatment of women with PMDD. First, a continuous exposure to hormones reminiscent of pregnancy could be an effective treatment for some women with PMDD (

44). Studies using oral contraceptives have confirmed their efficacy in some women with PMDD (

45–

50). However, our data suggest that continuous vs. interrupted oral contraceptive would be more effective, since the latter regimen would recapitulate changes in estrogen and progestin secretion that could induce symptoms, but perhaps at times in the 28-day cycle differing from those in the natural menstrual cycle. Certainly, women who are being treated with either leuprolide with the continuous add-back or those commencing oral contraceptives should be warned about the possible recurrence of symptoms during the first phase of the add-back. Additionally, it is possible, given the findings by Segebladh and colleagues (

31), that low-dose estradiol alone could be employed for some women with PMDD with proper monitoring of the endometrium. Finally, preliminary findings from a small trial of the 5α-reductase inhibitor dutasteride suggested that preventing the luteal phase increase in allopregnanolone levels mitigates symptoms in PMDD (

16). Thus, treatment strategies to attenuate or eliminate the change in estradiol and progesterone (or their metabolites) could effectively target the hormonal trigger in this condition.

Challenges and limitations of this study include the maintenance of the blind during active and placebo add-backs and the small sample size, which limit generalizability of our findings. First, the presence or absence of hot flushes or menstrual bleeding certainly could have suggested the presence of placebo or combined active add-back. Nonetheless, this was not a traditional clinical trial design to contrast ovarian steroid add-back with placebo add-back. Our main contrast was between the first month of active hormone add-back and months 2 and 3 of active add-back. Consequently, even if participants correctly inferred when they received active vs. placebo add-back (which was often not the case), the presence of PMDD symptoms during month 1 of estradiol/progesterone compared with months 2 and 3 confirms the study’s hypothesis. Second, although we observed a recurrence of symptoms in the daily ratings for irritability and sadness, it is possible that had we employed a larger sample, we would have identified significant changes in a broader range of PMDD symptoms. Additionally, our observed response rates are similar to those reported in several previous studies by our group (

14) and others (

4,

5,

9,

51,

52), and they suggest that ovarian suppression is not uniformly effective in PMDD. These observations suggest that additional clinical characteristics of women with PMDD could militate against the beneficial effects of ovarian suppression in PMDD. For example, Pincus et al. (

53) suggested the pattern of symptom variability in some women with PMDD was predictive of response to leuprolide. Our approach was to test a specific hypothesis about the role of ovarian steroids in a phenomenon that we identified in a prior publication (

14), and a homogeneous sample of women with PMDD with evidence of hormone sensitivity (confirmed by their response to leuprolide) was necessary to achieve this study goal. Indeed, in addition to identifying the change in ovarian steroids as the relevant symptom-producing stimulus, our findings also emphasize the heterogeneity and complexity of the effects of hormone change in PMDD. Two-thirds of the women with PMDD showed symptom suppression while taking leuprolide, and of those, 58% (seven of 12) showed symptom provocation when receiving estradiol/progesterone add-back. Our findings, therefore, apply only to a subgroup of women with PMDD. Most importantly, these findings advance our understanding of the effects of ovarian steroids in the pathophysiology of PMDD and related conditions.

In conclusion, our findings confirm that the change in ovarian steroids contributes to the onset of negative affective symptoms in women with PMDD. We did not distinguish between the effects of estradiol and progesterone on symptom onset since we did not administer and withdraw these hormones separately. Indeed, in our previous study (

14) we observed PMDD symptom recurrence after 2–3 weeks of either estradiol or progesterone, suggesting that both hormones have the capacity to induce symptoms, whereas findings by Segebladh et al. (

31) suggest that PMDD recurrence is limited to combined estradiol and progesterone and not induced by low-dose estradiol. These issues remain to be clarified in future studies. What also remains to be determined is why PMDD symptom recurrence is self-limited and symptoms remit despite continuing stable ovarian steroid levels. Presumably, homeostatic mechanisms are activated in relation to either the presence of the negative affective state or the presence of stable levels of ovarian steroids. The latter possibility has been described by Smith et al. in rodents, with alterations in GABA

A subunit conformations occurring after increases or decreases in progesterone or its neurosteroid metabolite allopregnanolone, but with conformations returning to normal during stable levels of these hormones (

17–

19). Although the mechanisms underlying the mood-destabilizing effects of ovarian steroids in PMDD remain to be better characterized, as does the source of susceptibility to this trigger, our findings provide a new target for interventions. Specifically, therapeutic efforts to inhibit the change in steroid levels proximate to ovulation, similar to those reported by Martinez et al. (

16), merit further study.