The rising costs associated with depression and anxiety constitute a major public health problem across the developed and developing world (

1). While the need to address the growing burden of these common mental disorders is not in doubt, there has been little consensus on how this should be executed. Although effective treatments are available, cost-effectiveness models suggest that even in the unlikely event of optimal treatment being delivered in all cases, only 35%–50% of the overall burden of depression and anxiety would be alleviated (

2). As a result, a number of agencies have begun to consider strategies aimed at primary prevention of both depression and anxiety.

Rose (

3) argued that the most appropriate method for preventing common, multifactorial diseases is to shift the entire population distribution of known risk factors. Such strategies are well established for the prevention of other conditions, such as cardiovascular disease. However, most of the known risk factors for depression and anxiety, such as familial risk, socioeconomic position, and life events, are difficult or impossible to modify (

4).

There is, however, some emerging evidence that lifestyle factors, such as physical inactivity, may be potential targets for strategies aimed at preventing depression and anxiety (

5,

6). A variety of health surveys have demonstrated a cross-sectional association between exercise and lower rates of both depression and anxiety (

7,

8). However, the possibility of reverse causation (low mood or anxiety leading to reduced levels of exercise) has limited the interpretation of such studies. To date, the results of prospective studies have been more mixed. Some studies have found no prospective association between levels of exercise and depression and anxiety (

9–

11), while others have suggested that any beneficial effects of exercise may be limited to certain subgroups or age groups, or only associated with intensive exercise (

12–

14). The evidence base has been further confused by many, but not all, of the published reports conflating depression and anxiety disorders, despite each having unique risk factors and distinct biological processes (

15). The evidence base for exercise as a treatment for current depression is more established, with numerous reviews concluding that exercise is moderately effective for reducing the symptoms of depression (

16,

17). Recent analyses of the data used in these reviews have added further evidence for the antidepressant effect of exercise, with findings that both publication bias and enhanced control group responses may have led to an underestimate of the true effect size of exercise as an intervention in depression (

18,

19). However, systematic reviews of the evidence for exercise in preventing new-onset depression and/or anxiety have needed to be more tempered in their conclusions, particularly regarding the relative importance of the intensity and amount of exercise required to convey any protective effect (

20).

A number of theories have been proposed as to how exercise may prevent mental illness, yet to date none of these have been formally evaluated in prospective epidemiological studies (

5). Exercise is associated with a number of biological changes that could have an impact on mental health. One purported biological mechanism is alteration in the activity of the autonomic nervous system (

21,

22). Regular exercise increases parasympathetic vagal tone, leading to physiological changes such as resting bradycardia (

23). Alterations in autonomic nervous system activity have been observed in those suffering from depression, and vagal nerve stimulation has been used to treat depression (

21). Other explanations for any association between exercise and depression and anxiety focus on the physical health, self-esteem, or social benefits of exercise.

Addressing the uncertainty surrounding the relationship between exercise and depression and anxiety is important. While many agencies are keen to promote the potential mental health benefits of exercise, at present the literature is unable to provide the most basic information needed for effective, targeted, evidence-based public health campaigns concerning depression and anxiety. The aim of the present study was to utilize a large (N=33,908) prospective cohort to address three questions. First, does exercise provide protection against new-onset depression and anxiety? Second, if so, what intensity and total amount of exercise is required to gain protection? Third, what causal mechanisms underlie any association between exercise and later depression and anxiety?

Method

Study Design

The HUNT study [Health Study of Nord-Trøndelag County] represents one of the largest and most comprehensive population-based health surveys ever undertaken. The Nord-Trøndelag County of Norway covers a mainly rural area, with a total population of 127,000 at the time of the study commencement. In phase 1 (HUNT 1) of the study, conducted between January 1984 and February 1986, all inhabitants of the county aged 20 years or older (N=85,100) were invited to complete questionnaires on their lifestyle and medical history and to attend a physical examination. A total of 74,599 individuals participated (87.7%). All participants were then followed up 9 to 13 years later (between August 1995 and June 1997) in phase 2 of the study (HUNT 2). Detailed information on the HUNT cohort study has been published elsewhere (

24,

25). The STROBE [Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology] checklist (see appendix SA1 in the

data supplement accompanying the online version of this article) was followed throughout the study.

Selection of a “Healthy” Sample

In order to be more confident regarding the direction of any associations found, data from HUNT 1 were used to select a “healthy” cohort, without any evidence of current physical illness or depressive or anxiety disorders at baseline.

Symptoms of depression and anxiety at baseline.

The presence of depression and anxiety at baseline (HUNT 1) was detected in two ways. Firstly, all participants completed the 12-item Anxiety and Depression Symptom Index. This measure, designed to capture a range of symptoms suggestive of depression and anxiety, has been validated and shown to have a good test-retest correlation (

26,

27). A total of 60,980 respondents (81.7%) returned an adequately completed questionnaire. Previously, a cut-off at the 80th percentile of the total score on the questionnaire has been used to define caseness (

28). In order to be more conservative in creating a “healthy” cohort, only those falling below the 70th percentile of the total score were selected (N=42,686). Secondly, participants were also asked whether they suffered from any impairments due to psychological complaints. An additional 726 individuals who indicated baseline psychological impairments were excluded.

Assessment of physical health at baseline.

Physical ill-health may prevent individuals from participating in exercise and is an independent predictor of common mental disorders (

29). Participants were asked whether they suffered from any impairments with regard to motor abilities or impairments due to physical illness, or suffered from, or had ever been diagnosed with, diabetes, angina, myocardial infarction, stroke, or cerebral hemorrhage. Consequently, an additional 8,444 participants were excluded, yielding a final “healthy” cohort of 33,908 individuals.

Measurement of Exercise at Baseline

At the time of their baseline assessment (HUNT 1), all participants were asked how often they engaged in exercise (such as walking or swimming). They were provided with five options: 1) never, 2) less than once a week, 3) once a week, 4) two to three times a week, and 5) nearly every day. Participants were asked, on average, how long they exercised on each occasion. By combining the answers for both of these questions, it was possible to produce an estimate of the total number of minutes per week each individual spent exercising. Participants were also asked about the intensity of their exercise, with three possible options: 1) exercise without becoming breathless or sweating, 2) exercise resulting in breathlessness and sweating, or 3) exercise resulting in near exhaustion. The last two options were combined into one category.

The reliability and validity of these questions and a composite total time spent engaging in exercise per week have been demonstrated against three additional objective measures of physical activity: maximal oxygen uptake, measures of body position and motion over 7 days using an ActiReg recording instrument, and the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (

30).

Assessment of Depression and Anxiety in HUNT 2

At follow-up (HUNT 2), all participants were asked to complete the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (

31). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is a self-report questionnaire comprising 14 4-point Likert-scale items covering anxiety and depression symptoms over the previous 2 weeks. A cut-off score of 8 in each subscale (anxiety subscale, depression subscale) has been found to be optimal for case finding, with sensitivity and specificity estimates of around 0.80 (

32).

Potential Confounding and Mediating Variables

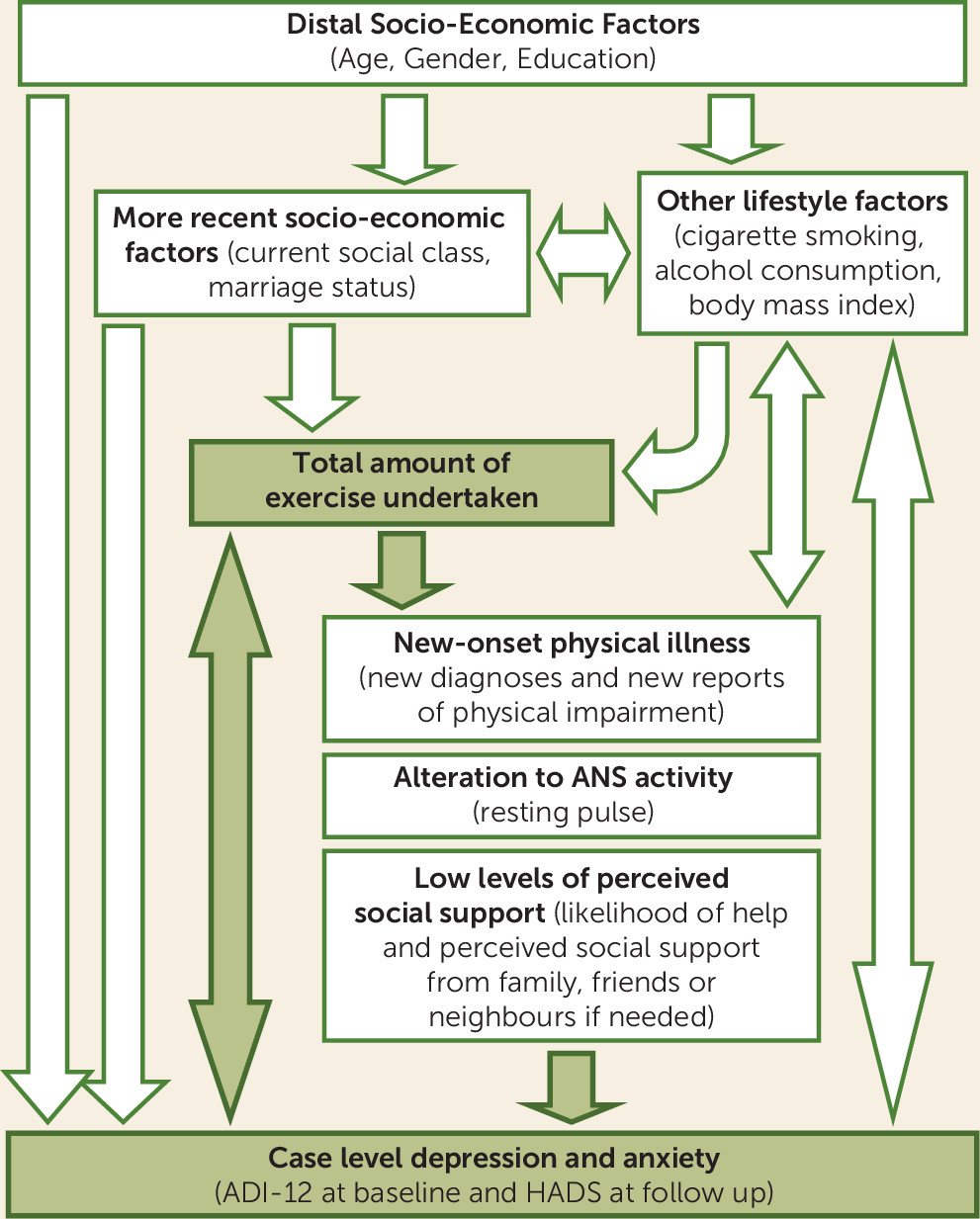

In order to facilitate the differentiating of confounders and mediators, a conceptual hierarchical framework (see

Figure 1) was constructed a priori to outline how various factors may relate to both exercise and depression and anxiety.

Demographic and socioeconomic factors.

Information on participants’ age, gender, and marital status was obtained from the Norwegian National Population Registry. Participants were asked to record their highest completed education level. Occupational social class was calculated according to the International Erikson-Goldthorpe-Portocareros classification (

33).

Substance use.

Participants were asked to report the total number of cigarettes consumed per day and how frequently they drank alcohol, with five options ranging from total abstainer to 10 or more times in the past week.

Body-mass index (BMI).

A specially trained nurse took measurements calculating the BMI of each participant.

New-onset physical illness.

The same somatic conditions and limitations that were considered at baseline as exclusion measures were also assessed at follow-up, allowing the identification of any new-onset illnesses or impairments throughout the course of the study.

Autonomic nervous system activity.

Lowered resting pulse is a biological adaptation to regular exercise (

34), due to increased parasympathetic vagal tone (

23). At the HUNT 1 physical examination, each participant’s resting pulse was measured after at least 4 minutes of rest in the sitting position by palpation over the radial artery for 15 seconds.

Perceived social support.

Each participant’s perceived social support (both instrumental and emotional) was assessed via a single question: “If you fell ill and had to stay in bed for a significant period, how likely do you think it is that you would get the necessary help and support from family, friends, or neighbors?” Five options were provided: 1) very likely, 2) quite likely, 3) doubtful, 4) unlikely, 5) not likely at all.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using STATA statistical software, Version 10.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex.) (

35). A multiple imputation model was constructed to replace missing values using the imputation by chained approach method. Thirty imputed data sets were created. All variables used in the analyses were included in the imputation model. Sensitivity analyses utilizing complete case analysis were undertaken to ensure results were not significantly altered by the multiple imputation process.

The associations between level of physical activity and both depression and anxiety were assessed using univariate and then multivariate logistic regression. The total amount of exercise undertaken each week was divided into six categories ranging from none up to more than 4 hours. The relative confounding effect of each of the variables outlined above was examined in turn, before a final multivariate model containing all potential confounders was constructed. Interactions by gender, age subgroup, and exercise intensity were tested using postestimation Wald tests. The correlation between levels of exercise at baseline and follow-up was examined using Spearman’s rank-order correlation tests. In addition to reporting odds ratios, the relative importance of exercise in predicting future depression and anxiety was examined using population attributable fractions.

Finally, the importance of the following three potential mediating factors was considered: 1) new-onset physical illness, 2) autonomic nervous system activity (resting pulse), and 3) the level of perceived social support. Although a “healthy” cohort was selected for this study, the possibility of reverse causation remained, with subthreshold symptoms of depression and anxiety leading to reduced levels of exercise. Therefore, a fourth potential pathway, reverse causation, was also considered. The associations between each of the four potential mediating factors and both exercise level and levels of depression and anxiety were examined using linear regression, before the effect of adding each potential mediating factor to a final model was assessed.

Ethics

Both the HUNT 1 and HUNT 2 phases of the study were approved by the National Data Inspectorate and the Board of Research Ethics in Health Region IV of Norway.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Sample

The characteristics of the “healthy” cohort of 33,908 individuals are summarized in

Table 1. Of these, 22,564 (66.5%) were successfully followed up at the HUNT 2 phase. Females (p<0.001) and younger participants (p<0.0001) were more likely to be followed up. The frequency of exercise undertaken at baseline did not predict loss to follow-up once the effect of gender and age was considered (p=0.19). Of the 22,564 individuals followed up, 1,578 (7.0%) developed case-level symptoms of depression, and 1,972 (8.7%) developed case-level symptoms of anxiety. All participants gave their informed consent to participate in this study.

Exercise at Baseline and New-Onset Depression and Anxiety

There was a negative relationship between the total amount of exercise undertaken at baseline and risk of future depression (p=0.001). In contrast, the prevalence of case-level anxiety was similar regardless of the levels of baseline exercise (p=0.21). Logistic regression models of the associations between the total amount of exercise at baseline and later depression and anxiety are displayed in

Table 2. After adjustment for a range of confounders, those who reported undertaking no exercise at baseline had a 44% (95% confidence interval

=17%–78%) increased odds of developing case-level depression compared with those who were exercising 1–2 hours a week. The models presented in

Table 2 confirm the lack of any association between baseline exercise levels and later case-level anxiety (p=0.27).

There was no evidence of interaction by gender (all p values >0.2) or when stratified by age group (greater than or less than 50 years old, p=0.96) in the association between the total amount of exercise at baseline and later case-level depression or anxiety. A similar significant association was seen between baseline levels of exercise and later depression in those aged less than 50 years (p=0.04) and those aged 50 years and older (p=0.03). As expected, there was a significant correlation between the amount of exercise undertaken at baseline and follow-up (p<0.001).

Dose-Response Relationship

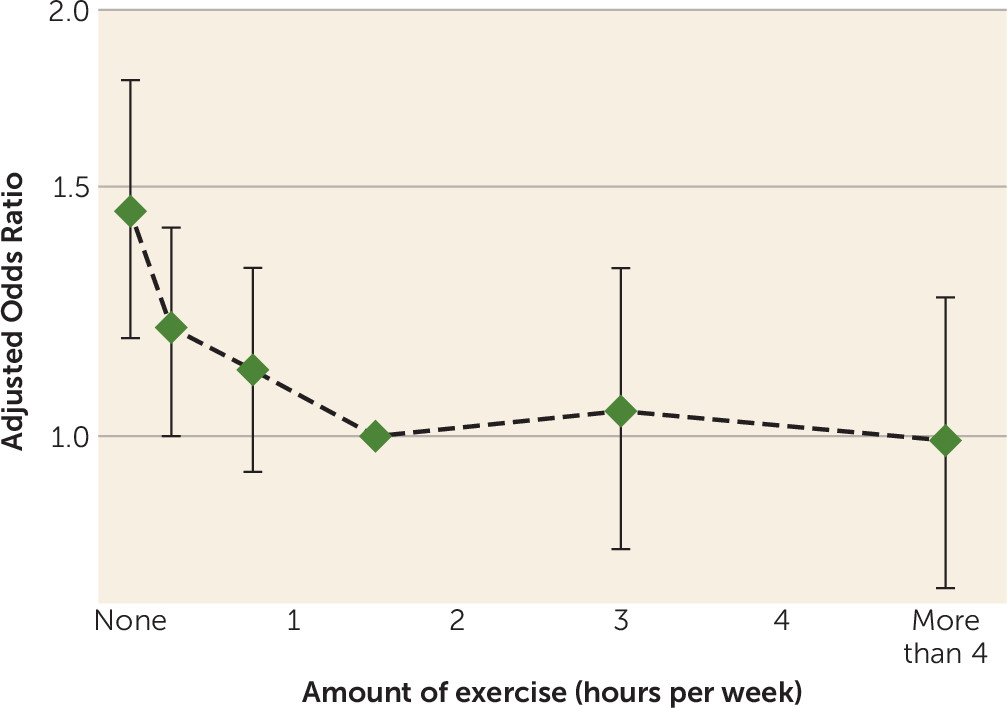

Visual representations of the dose-response relationship between total exercise at baseline and the odds of later case-level depression are provided in

Figure 2. Most of the protective effect of exercise is realized with relatively low levels of exercise, with no indication of any additional benefit beyond 1 hour of exercise each week. Maximum likelihood ratio tests suggest that an exponential decay model (with decreasing benefit as the total time of exercise increases) was a better fit for the data than a linear model (test for difference between models, p=0.004). The combined population attributable fraction for less than 1 hour of exercise per week was 11.9%. There was no evidence of an interaction by intensity of exercise (p=0.96).

Possible Mediating Pathways

In line with a priori predictions, those who engaged in less exercise at baseline tended to have higher resting pulse, lower levels of perceived social support, and more subthreshold symptoms of depression and anxiety, and they were more likely to develop new-onset physical illnesses over the course of the study (p<0.001).

Table 3 demonstrates that three of the four potential mediating pathways considered accounted for some of the observed association: reverse causation, lower levels of perceived social support, and new-onset physical illness. However, each of these modeled pathways explained only a very small proportion of the observed effect, with the majority of the protective effect of exercise remaining unaccounted for by measured factors.

Discussion

Using a large population cohort study, we have observed that relatively small amounts of exercise can provide significant protection against future depression but not anxiety. This protective effect was seen equally across all groups, regardless of the intensity of exercise that was undertaken or the gender or age of the participants. Assuming there is no residual confounding in our final model and the observed relationship is causal, our results suggest that if all participants had exercised for at least 1 hour each week, 12% of the cases of depression at follow-up could have been prevented.

The key strengths of this study are its large sample size, prospective data collection, use of validated measures of physical activity and mental disorder, and the detailed information available on a wide range of potential confounding and mediating factors. Despite these strengths, the analyses presented have some important limitations. Regarding the study design, while individuals reporting current symptoms and/or impairment of depression or anxiety at baseline were excluded using a two-step process, we were not able to exclude individuals with a history of prior episodes of depression and anxiety. Thus, it is possible that some individuals with a lifetime history of depression or anxiety may have been included in the “healthy” cohort, and thus a proportion of the future cases may be recurrent episodes of depression or anxiety. While the long follow-up time is a strength, the use of a single measure of a relapsing and remitting condition such as depression means that some misclassification will have occurred. Such misclassification is likely to be random and therefore results in regression dilution bias and an attenuation of effect sizes. This has important consequences for the interpretation of the results and suggests that the actual protective effect of exercise may be even greater than that reported in this study. The measurement of exercise at a single time point will also have created some misclassification, although there was a significant correlation between levels of exercise at baseline and follow-up. The majority of other limitations relate to the measures used. While the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is one of the most widely used and validated measures of depression and anxiety, the operationalization of any mental disorder via a self-report screening tool cannot be considered equivalent to a clinical diagnosis, and a risk of misclassification remains. Similarly, while the measures of exercise used have been extensively validated (

30), they remain reliant on self-report, and each factor considered in the analysis of mediation was measured with a single item that may not have fully captured the constructs being considered. In addition to standard regression, population attributable fractions were used to describe the relative importance of exercise as a possible preventative strategy. Population attributable fractions can be a useful way to help guide public health interventions, but any estimates of population attributable fractions assume a causal relationship with no residual confounding. While attempts were made to account for many confounders, a number of important potential confounding variables, such as personality, attitude toward health, diet, seasonal weather variations, and the degree to which each participant’s local environment is conducive to regular exercise, remained unmeasured. Nord-Trøndelag County is situated between northern latitudes 63° and 65°. As a result, there is considerable seasonal variation in the number of daylight hours. Previous studies have shown an associated seasonal variation in depression prevalence within Nord-Trøndelag County, with higher rates of depression between December and April (

36). If rates of physical activity were also lower in the winter months, then the confounding effect of the season at the time of assessment could affect any observed cross-sectional association between exercise and depression. However, this longitudinal study mitigates against this by the fact that there was no link between the seasonal timing of the assessments in HUNT 1 (when exercise levels were measured) and HUNT 2 (when levels of depression were assessed). The invitation for participation in the HUNT 2 phase was sent to all residents of the county at a time that was unrelated to when each individual had been assessed during the HUNT 1 phase. The equal popularity of both winter and summer sports in Norway may also have reduced the possibility of seasonal confounding.

This study represents, to our knowledge, the largest and most detailed modeling of the prospective dose-response relationship between exercise and depression and the first published epidemiological exploration of the causal pathways involved. In addition to confirming that more active individuals are less likely to develop depression, we were able to demonstrate that this was most accurately modeled as an exponential decay model, with decreasing benefit as the total time spent exercising increases. This supports and expands on the tentative conclusions from a review published in 2014, which highlighted that substantial mental health benefits may be gained from relatively moderate levels of exercise (

37). Importantly, the majority of the protective effects of exercise against depression are realized within the first hour of exercise undertaken each week, which provides some clues regarding causation and has major implications for possible future public mental health campaigns. The majority of studies examining the role of physical activity in preventing cardiovascular disease have found that the beneficial cardiovascular effects continue to increase up to around 2–3 hours of exercise per week (

38,

39). Thus, while there are similarities in the overall shape of the dose-response relationship between exercise and depression and exercise and somatic illness, the level of activity needed to realize the bulk of the possible protective effects are very different. Our finding that more vigorous-intensity exercise had no additional protective effects against future case-level depression is also in contrast to previous findings regarding protective factors against cardiovascular disease (

39).

Taken together, these results suggest that processes such as alterations in autonomic nervous system activity and modification of metabolic factors, which require more regular or strenuous exercise, may be less important when considering the protective effects of exercise against future depressive illness. In keeping with this hypothesis, our results suggest that the perceived social benefits of exercise may mediate some of the protective effects against depression. However, within our analysis, the increased levels of perceived social support accounted for only a small proportion of the effect observed, meaning the bulk of the observed protective effect remains unexplained. People’s perception of their social support may be subject to bias relating to their current mental state. This type of reporting bias could lead to an overestimate of the mediating effect of perceived social support, meaning an even greater proportion of the observed protective effect of exercise may be unexplained. We propose two possible explanations to account for the unexplained protective effect of exercise. Firstly, the remaining prospective associations may be due to confounding from factors not measured, such as shared genetic factors, personality, or individual attitudes toward health (

40). Secondly, or alternatively, there may be other causal factors not measured in this study, such as changes in self-esteem, serotonin release (

41), increased expression of neuroprotective proteins such as brain-derived neurotropic factor, altered hippocampal neurogenesis, or modifications to the activity levels of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (

42). The lack of any association between exercise and future anxiety disorders suggests that the link between exercise and depression is not merely related to a general increase in mental well-being and is unlikely to involve risk factors shared between depression and anxiety.

Despite the remaining uncertainty regarding causal pathways, the findings presented in this study have important public health implications. There is evidence that the levels of exercise in the general population in developed countries have decreased considerably over the recent decades (

43), with similar trends now also being observed in developing countries. The results of this study indicate that relatively modest increases in the overall amount of time spent exercising per week may be able to prevent a substantial number of new cases of depression. If causality is assumed and there are no other major cofounders, our results suggest that at least 12% of new cases of depression could be prevented if all adults participated in at least 1 hour of exercise each week. While education regarding the higher levels of exercise required to achieve maximum cardiovascular and metabolic benefits remains important, informing individuals that significant mental health benefits may be achieved with small changes in their behavior may be valuable in facilitating behavioral change. Given that the intensity of exercise does not appear to be important, it may be that the most effective public health measures are those that encourage and facilitate increased levels of everyday activities, such as walking or cycling. The results presented in this study provide a strong argument in favor of further exploration of exercise as a strategy for the prevention of depression.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Erlend Bergesen, who was initially involved in this study but, sadly, died in August 2006.