In recent years, an influx of adolescents and young adults without documented childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have presented to clinics with complaints of inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms, often inquiring about stimulant medication (

1–

3). It remains unclear whether this trend is driven by typically developing individuals seeking stimulant medication for cognitive enhancement or by individuals with late-onset ADHD that warrants medical treatment. Recent birth cohort studies support the phenomenon of late-onset ADHD, reporting a 2.5%−10.7% prevalence for a form of ADHD that first emerges in adolescence or adulthood (

4–

7). These studies claim that most adult ADHD cases (67.5%−90.0%) do not involve the experience of symptom onset in childhood. This claim is contrary to decades of research characterizing ADHD as a chronic neurodevelopmental disorder with symptoms that appear before age 12 (

8–

11). The authors speculate that late-onset ADHD may appear spontaneously, but critics suggest that these cases may also represent individuals with undetected childhood symptoms (i.e., late-identified rather than late-onset) (

12–

14).

Critics also suggest that late-onset ADHD prevalence may be inflated by methodological artifacts, such as reliance on ADHD screening instruments, inability to detect symptoms that emerged in long gaps between assessments, a false-positive paradox, and failure to consider other mental disorders, health problems, or substance abuse as the source of symptoms (

12–

14). If many late-onset cases are false positives, this may misinform the field’s understanding of ADHD as a chronic disorder and overstate its prevalence. On the other hand, true late-onset ADHD may partially explain the uptick in adolescents and young adults seeking first-time treatment for newly reported difficulties (

4–

7).

The present study investigates late-onset ADHD in the local normative comparison group of the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD, which was designed to carefully assess ADHD symptoms over time (

15,

16). For 14 years from childhood to adulthood, comparison participants underwent comprehensive psychiatric evaluations with multi-informant assessment of ADHD symptoms and impairments (

17,

18). Due to the frequency (eight time points) and comprehensiveness of these assessments, ADHD symptom onset, other mental disorders, impairments, and substance use can be isolated temporally and considered when determining the history and nature of potential late-onset cases. Through careful review of multi-informant, longitudinal psychiatric data using a stepped diagnostic procedure that pinpoints symptom origins, we aimed to 1) understand what proportion of individuals with reported late-onset ADHD symptoms represent true cases of the disorder and 2) provide detailed clinical profiles for identified late-onset ADHD cases. Our procedure complements the epidemiological population studies by exploring the nature of late-onset ADHD after addressing previously noted methodological confounds and illustrating how late-onset ADHD might emerge over time (

12–

14).

Discussion

The local normative comparison group of the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD provided a unique opportunity to study detailed fluctuations in ADHD symptoms over time in adolescents and young adults without a childhood history of ADHD. After using a stepped diagnostic procedure that carefully considered multi-informant data, longitudinal symptom patterns from childhood to adulthood, impairment, co-occurring mental disorders, and substance use, approximately 95% of case subjects who initially screened positive for late-onset ADHD were excluded from diagnosis (

Table 2). These data indicate that when assessing adolescents and young adults for first-time ADHD diagnoses, clinicians should obtain a thorough psychiatric history and assessment of current functioning. Furthermore, 53% of adolescents and 83% of adults who met all symptom, impairment, and late-onset criteria for ADHD were excluded because symptoms or impairment were better explained by heavy substance use or another mental disorder (

Table 2) (also see the

online data supplement). Therefore, previously reported late-onset ADHD prevalence rates (2.5%−10.7%) may be overestimated due to limited ability to consult multi-informant data, track symptoms in extended gaps between assessment points, and review detailed patterns of substance use and comorbidity over time when determining diagnosis (

4–

7).

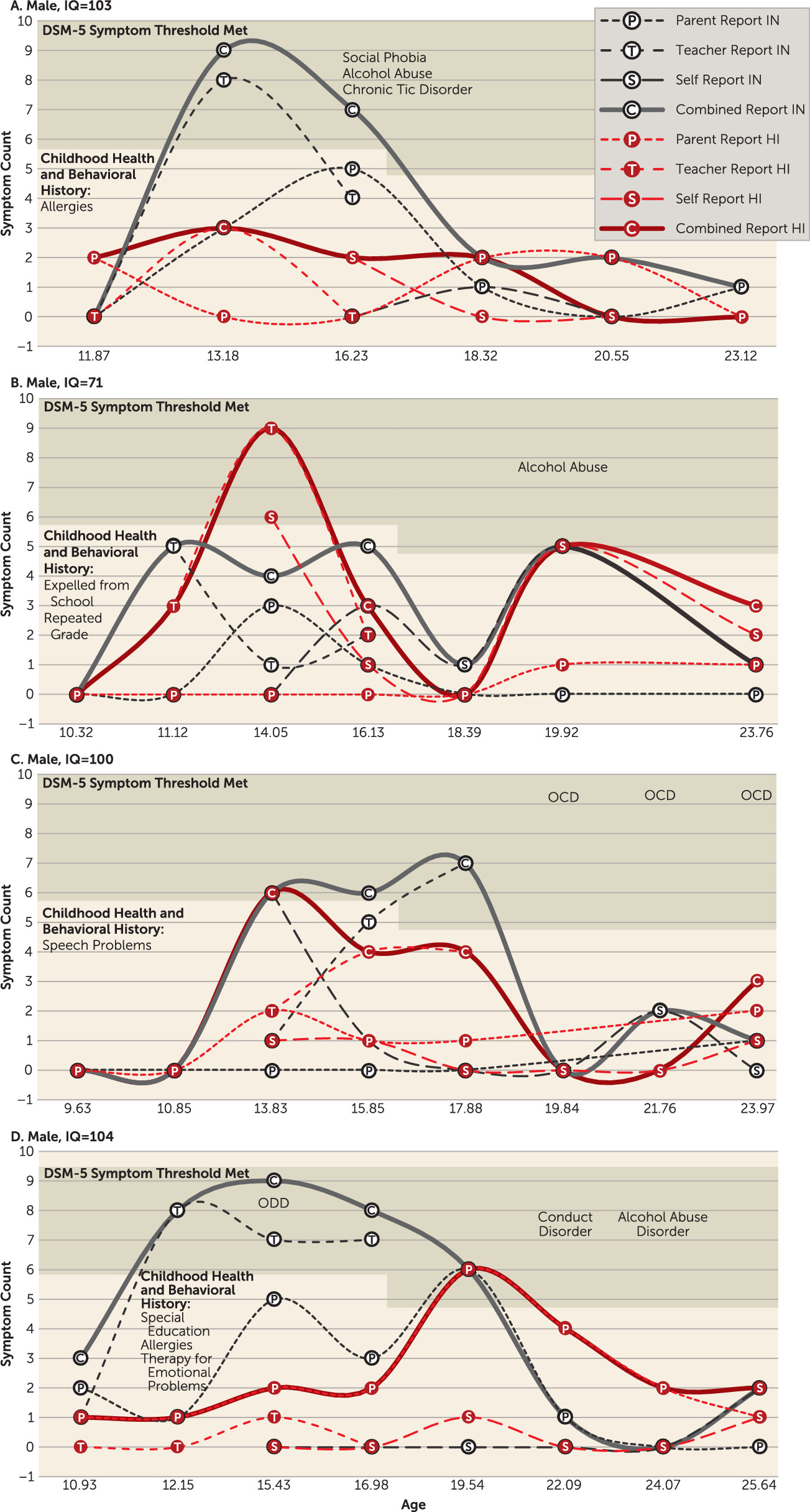

Six adolescent-onset ADHD case subjects appeared in the comparison group. One form of adolescent-onset ADHD (N=4) was adolescence-limited (

Figure 1) and characterized by above-average childhood symptoms, borderline to average intelligence, and symptom remission by age 19. In all four of these cases, the preponderance of symptoms was reported by teachers, although corroborated by parents and the adolescents. One explanation for this pattern is developmental misfit that mimics or facilitates inattention symptoms. Mounting environmental demands in adolescence may temporarily exacerbate above-average but subthreshold childhood ADHD symptoms (

Figure 1) or create cognitive overload for adolescents with slower developing prefrontal regions (

36,

37). In absence of mature executive functions, some adolescents may also display deficient self-control in socially or emotionally salient contexts, leading to adolescence-limited behavior problems that may be perceived as hyperactive/impulsive symptoms by raters (

38). Further work is needed to better understand this adolescence-limited presentation and the influence of cognitive development on ADHD-like symptoms in adolescents without childhood ADHD.

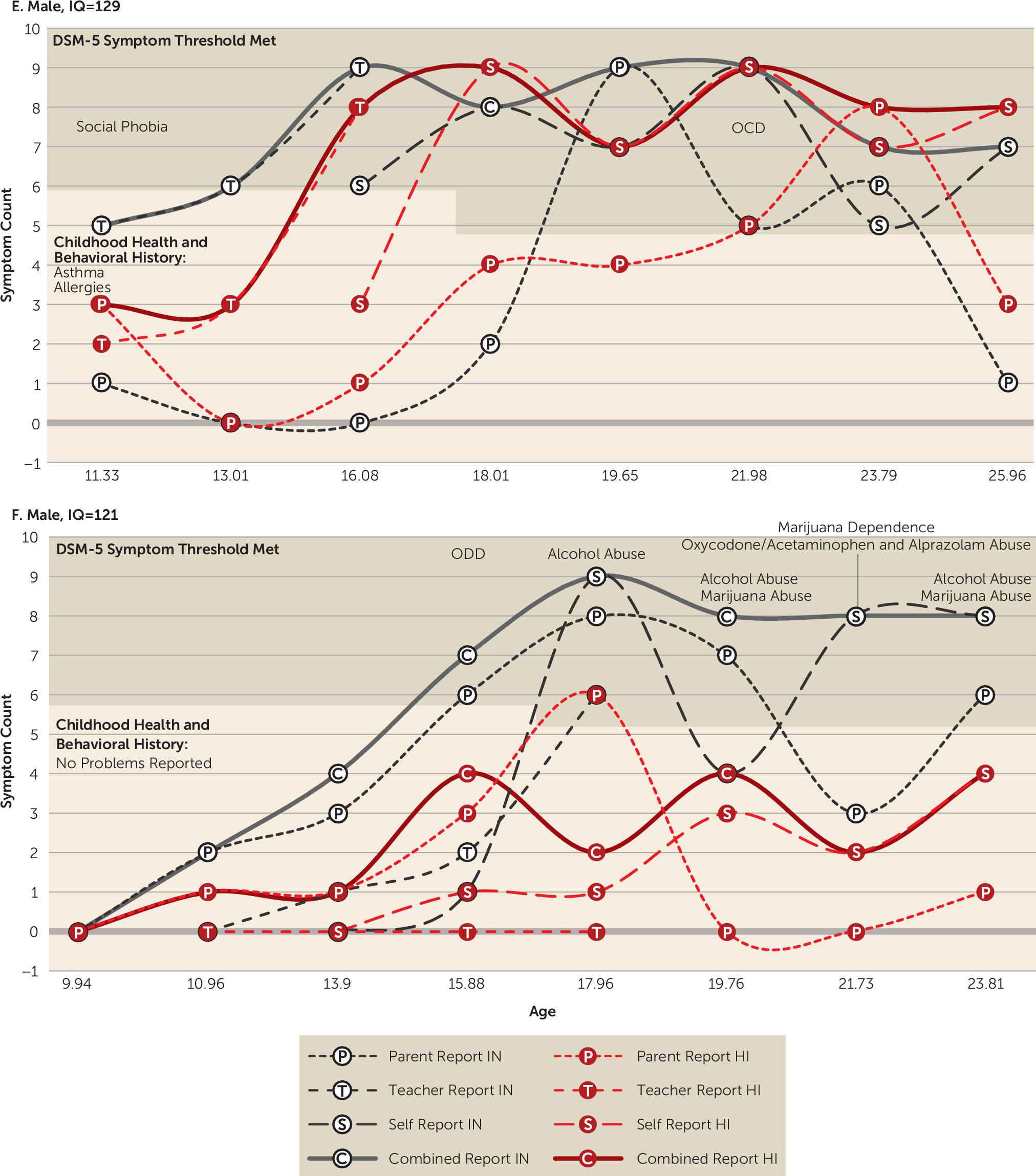

A second adolescent-onset ADHD presentation was characterized by above-average childhood ADHD symptoms and superior intellect (

Figure 2). Two male subjects with superior IQs exhibited a persistent form of late-onset ADHD with slowly escalating symptoms from childhood through young adulthood. This profile echoes previous findings that childhood ADHD symptoms may be masked in individuals with cognitive strengths, delaying initial ADHD diagnosis (

1). Since symptoms were likely present but mitigated in childhood, these individuals might better be characterized as late-identified, rather than late-onset, ADHD cases (

39).

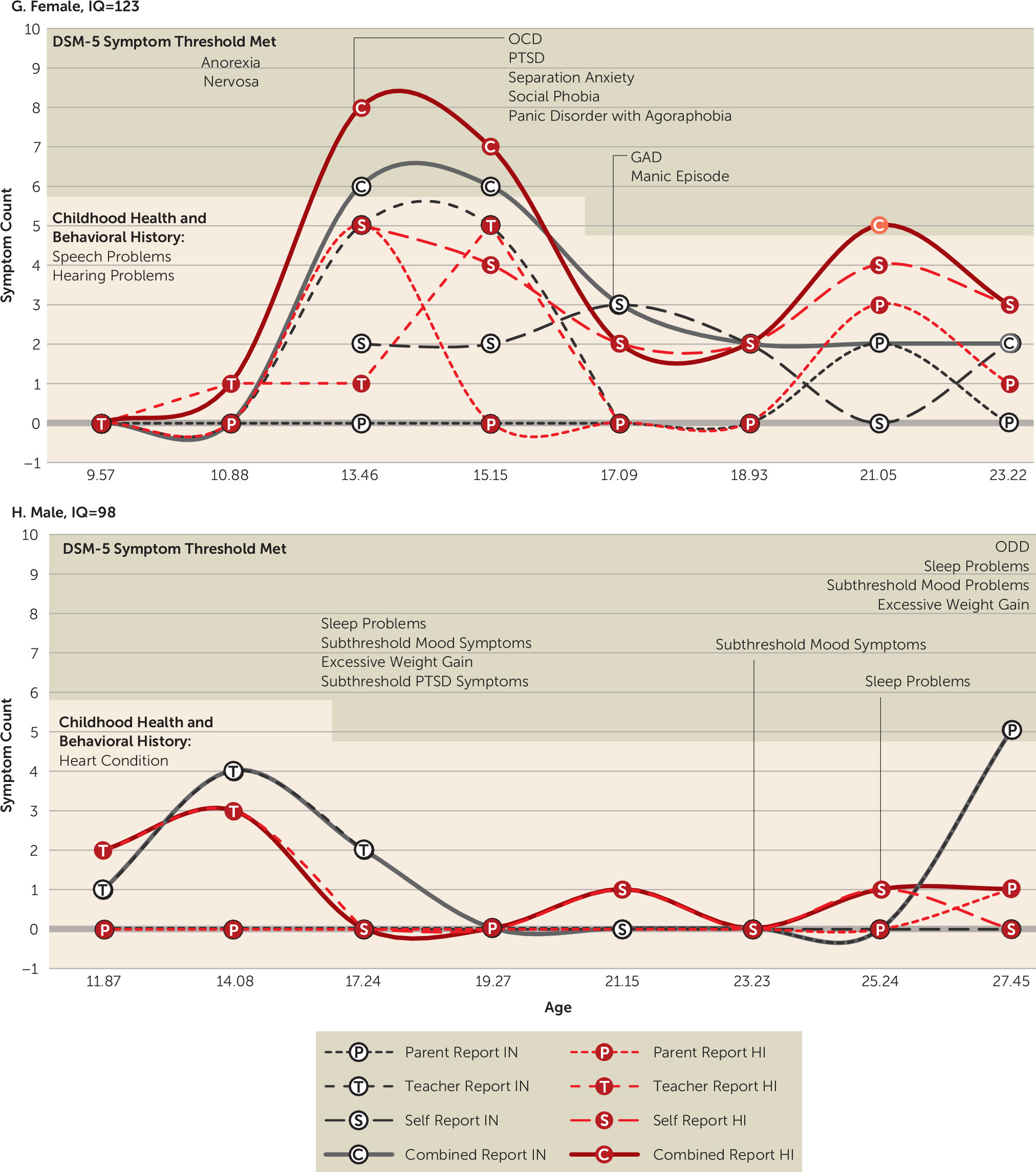

The Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD comparison group did not support adult-onset ADHD independent of a complex psychiatric history. The two case subjects identified as adult-onset both possessed a variety of past or current mental health symptoms (

Figure 3). In both cases, it was difficult to disentangle the etiology of these individuals’ symptoms, and thus the panel conservatively voted to retain the cases. In line with the false-positive paradox (

8), the vast majority of case subjects who initially met late-onset symptom and impairment criteria were excluded from diagnosis because of clear evidence that heavy substance use or another mental disorder better accounted for symptoms or impairment (

Table 2). In fact, the majority of impairing late-onset ADHD symptoms in young adulthood could be traced to heavy substance use (

Table 2) (also see the

online data supplement). There are still other potential causes of late-onset symptoms, such as brain injury, illness, or trauma, that should also be considered in future investigations. Without clear exclusionary guidelines for ADHD in adolescents and adults, there is risk that ADHD may become a catchall diagnosis for executive dysfunction stemming from any source. It is unclear whether ADHD-like presentations stemming from nontraditional sources should be differentiated from a chronic form of ADHD with developmental origins, although treatment may be similar (

40). Despite many strengths to birth-cohort samples, they are limited because they do not possess the detailed and frequent data collection required to carefully follow psychiatric functioning over time. One of the studies also did not perform full childhood diagnostic assessments, which may have led to missed childhood symptoms in some cases (

5). Of course, the average age at comparison baseline was approximately 10 years old, limiting our study’s ability to consider detailed symptom records before this assessment.

The comparison group was drawn from the same local school, sex, and age/grade pool as the ADHD sample, which may over-represent certain characteristics, such as male sex or slightly above-average family income. During adolescence, impairment ratings were only available from parents. Some case subjects may have met impairment criteria in adolescence if teacher or self-ratings had been available. We assessed case subjects only to the mid-to-late 20s. New late-onset cases might appear later in development. We also did not collect comprehensive data on physical health or personality disorders with impulsive features that may better explain late-onset cases. Because only eight late-onset cases were detected, we were insufficiently powered to conduct analyses comparing late-onset cases with other subgroups.