In the most common form of sequential combination treatment, a second treatment is added if a patient does not remit after an adequate trial with the initial intervention. Most sequential treatment studies have examined the efficacy of augmenting an initial antidepressant with a second psychopharmacological agent (

10), and a smaller body of literature has examined the addition of psychotherapy (

8). Adding a course of evidence-based psychotherapy to antidepressant medication after nonremission improves depression rating scores and reduces the probability of recurrence over the subsequent 1–2 years (

8,

11). The protective effect of CBT against recurrence is particularly evident if the antidepressant medication is discontinued during maintenance treatment (

12,

13). The less common sequential treatment model involves adding a second treatment, usually psychotherapy, to prevent recurrence after remission with the initial treatment (

8). Remarkably, although most depressed patients prefer psychotherapy (

14) and leading treatment guidelines recommend an evidence-based psychotherapy as an initial intervention for all but the most severely ill patients (

15,

16), only one randomized trial has examined the value of sequentially adding antidepressant medication to psychotherapy, finding improved outcomes among 17 nonresponders to psychodynamic psychotherapy (

17). Thus, the evidence base is limited regarding whether adding an antidepressant to the treatment regimen for patients whose depression has not remitted in response to CBT improves acute outcomes and protects against recurrence.

Here, we report the results of phase 2 of the Predictors of Remission in Depression to Individual and Combined Treatments (PReDICT) study. In phase 1, patients were randomly assigned to a 12-week course of CBT or antidepressant medication. Patients who did not achieve remission with this monotherapy in phase 1 were provided a second 12-week course of treatment, phase 2, in which the complementary treatment was added to their initial treatment. Demographic, clinical, and patient preference variables were examined as potential predictors and moderators of outcomes. Patients who responded to treatment or achieved remission by the end of phase 2 were eligible to enter an 18-month follow-up phase assessing relapse and recurrence. The outcomes from the follow-up phase and the impact of residual symptoms on relapse or recurrence were also explored.

Results

Patient Flow During Combination Treatment

The disposition of patients through the study is presented in Figures S1 and S2 in the

online supplement. In phase 1, 251 patients completed monotherapy, including 114 who achieved remission (

32). Of the remaining 137 patients, 13 were not offered combination treatment because the second phase of the study had not yet been initiated and 12 declined to continue into combination treatment, resulting in 112 participants entering phase 2. Of these phase 2 participants, 37 had received CBT in phase 1 and had escitalopram added in phase 2 (CBT plus medication), and 75 patients (30 taking duloxetine and 45 taking escitalopram) had received medication in phase 1 and had CBT added in phase 2 (medication plus CBT). Fifteen (13.4%) individuals did not complete phase 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of the phase 2 sample are summarized in

Table 1. Among the 112 patients starting phase 2 treatment, 71 had not responded to treatment and 41 had responded but had not achieved remission at the end of phase 1. During phase 1, the nonresponders had experienced a significantly smaller percentage reduction in HAM-D scores than the responders (20.6% [SD=21.2] and 61.5% [SD=9.7], respectively; p<0.001) and had significantly higher week 12 HAM-D scores (15.3 [SD=4.6] and 7.9 [SD=2.4], respectively; p<0.001). Those in the CBT plus medication group had significantly higher scores on the HAM-D (t=2.30, p=0.021) and the HAM-A (t=1.97, p=0.049) than those in the medication plus CBT group at phase 2 baseline. We did not compare outcomes or moderators of response between the groups because of the nonrandomized nature of phase 2.

Treatment Features

In phase 2, the mean number of CBT sessions attended in the medication plus CBT group was 13.4 [SD=2.9]; for the CBT plus medication group, the mean number of CBT booster sessions attended was 2.08 [SD=1.04]. Of the 15 therapists who delivered CBT, all but two had mean scores >40 on the independently rated Cognitive Therapy Scale, and the mean scores for the remaining two were just slightly below 40. Among the patients starting phase 2, the mean dosages of escitalopram and duloxetine at the beginning of phase 2 were 17.6 mg/day [SD=0.4] and 53.4 mg/day [SD=1.2], respectively. Seventy-nine percent of patients were titrated to the maximum dosage (20 mg/day of escitalopram or 60 mg/day of duloxetine) at some point during phase 2. The daily number of pills taken did not significantly differ across the groups, both at the end of phase 2 and at the final visit during follow-up (p>0.05). The mean phase 2 endpoint medication dosages for the CBT plus escitalopram, escitalopram plus CBT, and duloxetine plus CBT groups were 16.1 mg/day (SD=0.5), 18.0 mg/day (SD=0.4), and 55.5 mg/day (SD=1.0), respectively. The proportions of long-term follow-up patients who discontinued the antidepressant during the phase 2 combination treatment or during the follow-up phase, and the mean duration of antidepressant use during follow-up, did not meaningfully differ between the CBT plus medication and medication plus CBT groups (see Tables S1 and S2 in the online supplement).

Completion Rates

Completion rates were similar in both treatment groups (CBT plus medication: 84%; medication plus CBT: 88%). Patients who completed the study, compared with patients who did not, did not differ significantly on mean HAM-D scores at phase 2 baseline (12.4 [SD=5.4] and 13.7 [SD=4.4], respectively; t=0.906, df=110, p=0.37). However, the mean HAM-A score at phase 2 baseline was significantly lower among patients who completed the study than those who did not (10.4 [SD=4.9] and 13.9 [SD=5.3], respectively; t=2.48, df=110, p=0.015).

Outcomes

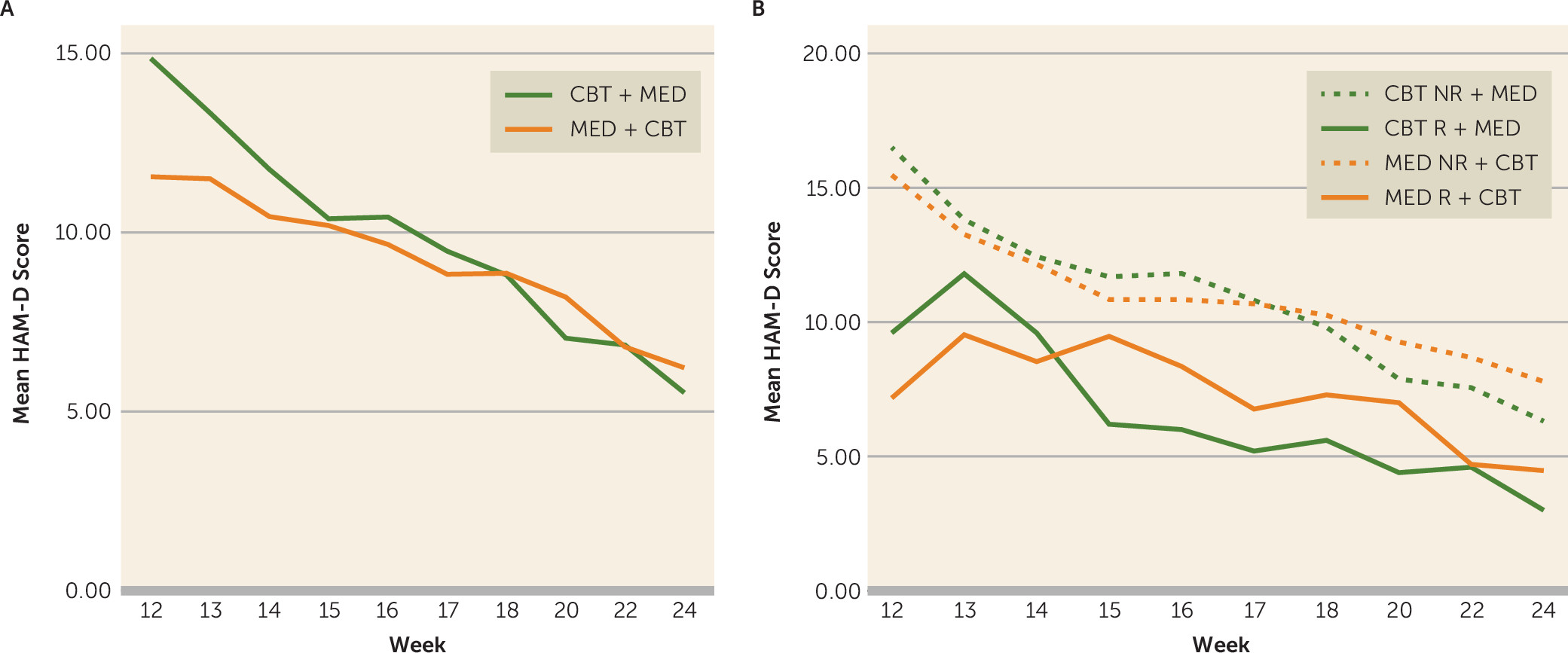

The mean estimated overall improvement on the HAM-D, the primary outcome, was 8.2 (SD=2.0) for the CBT plus medication group (t=8.28, p<0.0001) and 5.3 (SD=1.2) for the medication plus CBT group (t=8.85, p<0.0001). The raw mean values for HAM-D scores during phase 2 for the two treatment arms are presented in

Figure 1A.

Using the protocol definition of remission, 54 of 112 (48.2%) achieved remission during phase 2 (CBT plus medication: 20/37, 54.1%; medication plus CBT: 34/75, 45.1%), and an additional 31 patients (27.6%) achieved response without remission. Response rates were 76% in both the CBT plus medication group (28/37) and the medication plus CBT group (57/75). Using the last observation carried forward method and defining remission as a final-visit HAM-D score ≤7 resulted in remission rates of 64.9% (24/37) for the CBT plus medication group and 60% (45/75) for the medication plus CBT group.

Table 2 summarizes the phase 2 outcomes by level of response in phase 1. Overall, patients who responded to the phase 1 monotherapy but did not achieve remission had significantly better outcomes in phase 2 than patients who did not respond to the phase 1 monotherapy (χ

2=6.01, df=2, p=0.049). Trajectories of treatment response during phase 2 are illustrated in

Figure 1B.

Predictors of Remission

Table 3 presents the predictive significance for phase 2 remission of the demographic and clinical variables using an alpha level of 0.0047 to account for multiple testing. The severity of HAM-D and HAM-A scores at phase 2 baseline were the only significant predictors of remission (HAM-D: estimate=−0.127, SE=0.045, p=0.004; HAM-A: estimate=−0.180, SE=0.048, p=0.0001). Table S3 in the

online supplement contains test statistics of the prediction of remission during either phase 1 or 2 (N=251). In addition to baseline HAM-D scores (χ

2=6.44, df=1, p=0.011) and baseline HAM-A scores (χ

2=11.11, df=1, p=0.001), the presence of a current anxiety disorder also predicted nonremission (χ

2=6.86, df=1, p=0.009) in either phase.

Because of the strong predictive effects of both depression and anxiety severity on remission, we examined whether significance for each persisted when controlling for the other. After controlling for the HAM-A score, the prediction of remission by HAM-D score at phase 2 baseline was no longer significant (estimate=−0.040, SE=0.057, p=0.485). In contrast, the prediction of remission by HAM-A score remained significant when controlling for HAM-D score (estimate=−0.155, SE=0.059, p=0.009).

To evaluate whether anxiety was associated with treatment exposure, we examined the intensity of treatment exposure for anxious patients, a group defined as having a current comorbid anxiety disorder or having a HAM-A score above the median value. During phase 1 treatment, medication-treated patients with a comorbid current anxiety disorder were prescribed significantly more pills per day than those without a comorbid anxiety disorder (p=0.009); this difference fell short of significance when the two antidepressants were analyzed separately (escitalopram: 17.2 mg/day [SD=5.4] compared with 15.5 mg/day [SD=4.6], respectively, p=0.082; duloxetine: 45.6 mg/day [SD=15.0] compared with 51.3 mg/day [SD=14.4], respectively, p=0.06). No association with dosage in phase 1 was found using a median split of baseline HAM-A scores. During phase 2, neither definition of anxiety was associated with differences in medication dosage. For patients receiving psychotherapy, neither definition of anxiety was significantly associated with CBT session attendance during phase 1 or 2.

Effects of Preferences on Outcomes

Preference data at phase 1 baseline were obtained for all but one of the 112 participants. Seventy-four (66%) participants expressed a treatment preference (CBT: N=41, 36.6%; medication: N=33, 29.7%). To determine whether treatment preference led to dropout, we examined whether entry into phase 2 was more or less likely among patients who received their preferred treatment in phase 1. No difference was observed in phase 2 participation between participants who received their preference in phase 1 and those who did not (χ2=0.01, df=1, p=0.94).

Nineteen (46.3%) of the patients who preferred CBT and 22 (66.7%) of the patients who preferred medication received their preferred treatment during phase 2. Dropout occurred in five of 35 (14.3%) patients who did not receive their preferred treatment during phase 2, compared with four of 39 (10.3%) who received their preferred treatment and six of 37 (16.2%) who did not express a preference. No significant differences in rates of response were observed between patients who did and did not receive their preferred treatment during phase 2 (29/39, 74.4% compared with 25/35, 71.4%; χ2=0.08, df=1, p=0.78), remission (16/39, 41.0% compared with 14/35, 40.0%; χ2=0.01, df=1, p=0.93), or endpoint HAM-D score (7.9 [SD=5.7] compared with 7.7 [SD=6.4]; p=0.84).

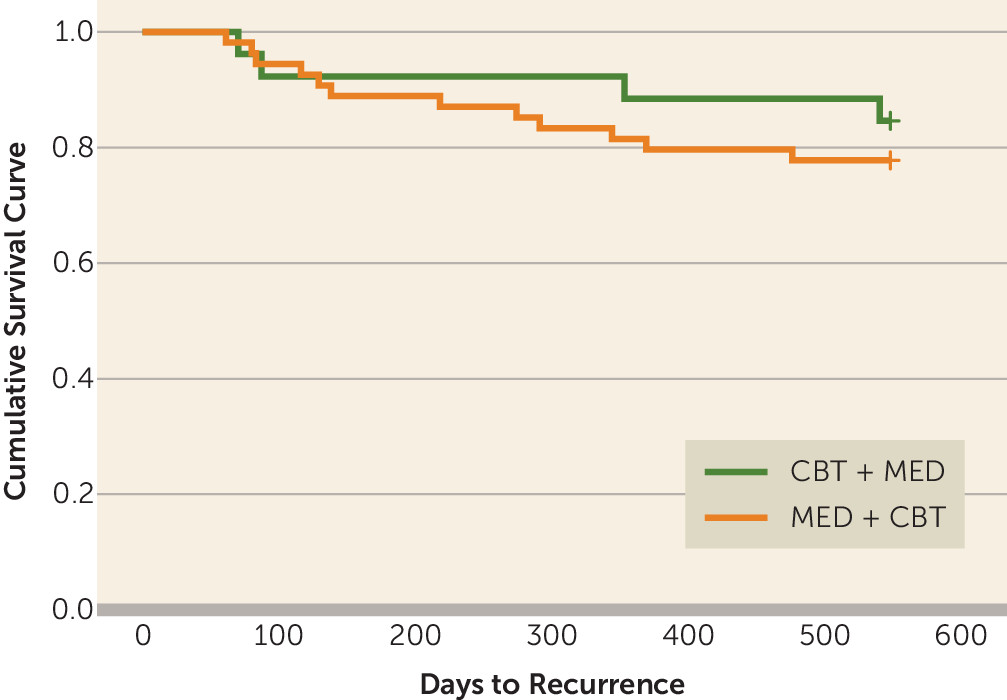

Recurrence During Long-Term Follow-Up

Among the 97 patients who completed phase 2, 80 (82%) participated in at least one follow-up assessment of relapse or recurrence (CBT plus medication: N=26; medication plus CBT: N=53; see Figure S2 in the

online supplement). Sixteen experienced recurrence of depression (20%)—four (15.4%) from the CBT plus medication group and 12 (22%) from the medication plus CBT group. Fifty (62.5%) of the 80 follow-up participants had achieved remission at the end of phase 2. In an exploratory analysis of this subsample, the relapse or recurrence rate among responders who did not achieve remission by the end of phase 2 (N=9/30, 30%) was higher than the rate among those who achieved remission (N=7/50, 14%), but the difference fell short of statistical significance (χ

2=3.00, df=1, p=0.083). The overall mean number of days until relapse or recurrence was 226.8 (CBT plus medication: 262.5 [SD=225.8]; medication plus CBT: 214.9 [SD=134.9]) (

Figure 2). There was no significant difference in anxiety scores at the end of phase 2 between those who experienced recurrence during follow-up and those who did not have a recurrence (mean HAM-A score: 4.20 and 5.69, respectively; t=1.45, df=78, p=0.15).

Taking both treatment phases into account, 174 patients (94 patients who achieved remission in phase 1 plus 80 patients who responded to treatment or achieved remission during phase 2) provided long-term follow-up data. In total, 29 (16.7%) met criteria for relapse or recurrence of depression during the follow-up.

Outcomes From Phase 1 Baseline to Week 24

Finally, we examined the degree of improvement in HAM-D score after 24 weeks of treatment between those originally randomized to CBT, duloxetine, or escitalopram, regardless of whether they achieved remission in phase 1 or continued to phase 2. One-hundred and ninety individuals had week 24 data available, 93 of whom achieved remission during in phase 1 and 97 of whom completed phase 2. We conducted a one-way ANOVA of improvement scores and found no group differences between individuals who received the three treatments (F=0.873, df=2, p=0.423). This result indicates that the degree of improvement was roughly equivalent regardless of initial treatment modality within a protocol initiating one treatment (either CBT or medication) followed by the addition of a complementary treatment if remission had not been achieved by 12 weeks.

Using the last HAM-D observation carried forward from the beginning of phase 1 in the PReDICT study’s total modified intent-to-treat sample (N=316), 205 (64.9%) patients achieved remission (defined as a last observed HAM-D score ≤7), an additional 29 (9.2%) attained response without remission, and 82 (25.9%) did not respond to treatment.

Discussion

Phase 2 of the PReDICT study was the first large trial to examine the sequential addition of CBT for patients who had not achieved remission with medication alone compared with addition of an antidepressant medication for patients who had not achieved remission with CBT alone. The results provide information relevant for practicing clinicians. First, the sequential addition of CBT for patients who have not achieved remission with antidepressant medication is an effective approach, as suggested by previous studies (

8). Second, the addition of antidepressant medication was effective for patients who did not respond to treatment or did not achieve remission with CBT, indicating that antidepressants are effective even for residual symptoms in patients who have not achieved remission with CBT. Third, remission rates were similar regardless of the sequence of the treatment administration. Fourth, both treatment sequences proved equally helpful in preventing relapse or recurrence of depression. Thus, the sequential order for applying CBT and medication does not meaningfully affect acute or long-term treatment goals. Fifth, patient preferences for a specific treatment modality did not affect outcomes of combination treatment, which is consistent with the small or negligible effects found in comparisons of monotherapy (

24,

33) and in meta-analyses (

34,

35), although one large trial found that preference exerted a strong effect (

36). Finally, after controlling for severity of depression, the level of anxiety at the time of starting combination treatment significantly predicted nonremission, as reported in other trials (

37,

38), indicating the need to incorporate interventions targeting anxiety in depressed patients.

The outcomes from the combination treatments in phase 2 of PReDICT differed based on the level of improvement with the first treatment. Among patients who did not respond to the first treatment, the addition of the second treatment resulted in remission rates of about 40%, regardless of whether the first treatment was CBT, escitalopram, or duloxetine. In contrast, patients who responded but did not achieve remission with the first treatment had substantially better outcomes with the addition of the second treatment, with 61% achieving remission after the addition of CBT to medication and 89% achieving remission after the addition of escitalopram to CBT. This finding that patients who responded to monotherapy but did not achieve remission improved more than patients who did not respond to monotherapy replicates the effect found among medication-treated patients in the large Research Evaluating the Value of Augmenting Medication With Psychotherapy (REVAMP) trial (

39), and the present results extend that conclusion to patients initially treated with psychotherapy.

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of adding psychotherapy to an antidepressant to address residual depressive symptoms (

8). In contrast, there is a dearth of studies examining the addition of medication for patients who respond to psychotherapy. In our sample, 89% (8/9) of patients who responded to CBT in phase 1 achieved remission in phase 2, indicating that antidepressants are effective for patients who respond to CBT but fall short of full remission. Although this finding may seem to contradict the meta-analyses that suggest that antidepressants are more effective than placebo only among severely ill patients (

40,

41), results from other analyses (

42,

43) and from studies of dysthymia (

44) demonstrate the efficacy of antidepressants in patients with milder forms of depression. The efficacy of antidepressants for mild symptoms has also been supported by a nonrandomized study of women with recurrent depression in which Frank and colleagues (

45) observed a 67% remission rate after addition of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) to ongoing interpersonal psychotherapy after nonremission with psychotherapy alone.

In comparison, trials in which patients who did not respond or did not achieve remission with an antidepressant or psychotherapy were switched to the alternative treatment have generally found lower rates of improvement. Among chronically depressed patients initially randomized to 16 weeks of the cognitive-behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP) or to treatment with nefazodone and failed to respond, remission rates among those switched to the psychotherapy were nonsignificantly higher than those switched to nefazodone (36% and 27%, respectively) (

46). This result differs from ours, but the studies are not directly comparable because in PReDICT the initial treatment was continued during the second phase, whereas in the nefazodone/CBASP trial the initial treatment was terminated when the second treatment was started. In the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression study (STAR*D), among patients who did not achieve remission with 12–14 weeks of citalopram and were randomly assigned to switch to either CBT or an alternative antidepressant medication, remission rates were also relatively low (25% and 28%, respectively) (

47). The substantially lower remission rates observed in these switch trials compared with the combination trials reviewed above suggest that a combination of psychotherapy and medication may be superior to switching between these modalities for most patients who have not achieved remission. However, not all sequential combination trials have found high levels of remission. In STAR*D, patients who did not achieve remission with citalopram experienced relatively low rates of remission whether they were assigned to receive sequential addition of CBT or augmentation of citalopram with buspirone or bupropion (CBT addition, 23%; medication augmentation, 33%) (

47). In the REVAMP study, patients with recurrent depression who did not achieve remission after 12 weeks of pharmacotherapy were randomly assigned to an additional 12 weeks of added CBASP, supportive therapy, or continued pharmacotherapy alone, with roughly equivalent remission rates (approximately 40%) across the three treatment arms (

39). Thus, although the evidence supports sequential combination over switching for patients who do not achieve remission with monotherapy, differences in the types of interventions and the characteristics of the patients analyzed across studies prohibit definitive conclusions, particularly considering the difference in prior levels of treatment exposure across the study samples.

For prevention of relapse or recurrence, the benefits of sequentially adding psychotherapy after monotherapy with medication are well established and are supported by the present study. The preventive efficacy of CBT-based psychotherapies is most evident when the antidepressant is discontinued during follow-up (

11,

13). As with acute treatment outcomes, the benefits of added medication to prevent relapse or recurrence are less well established. Some support is found in a large randomized trial of patients who responded to acute CBT but who were considered by the investigators to be at high risk for relapse. In these patients, continued CBT or a switch to fluoxetine produced equally low rates of relapse or recurrence (about 18%), and both were superior to placebo (33%) during 8 months of maintenance treatment; by the end of an additional 24 months of observational follow-up, rates of relapse or recurrence remained similar between the two active treatment arms (

48). The maintenance benefits of an antidepressant were also demonstrated in the 2-year follow-up phase of the previously cited study by Frank and colleagues (

45). In that study, patients requiring an SSRI plus interpersonal therapy to achieve remission experienced a 50% recurrence rate after tapering the SSRI, roughly double the 26% rate among those patients who achieved remission with interpersonal therapy alone (

45). These findings, combined with the results from the present analysis, justify the addition of antidepressant medication to reduce the risk of relapse or recurrence among patients who do not achieve remission with CBT alone.

In a previous analysis of the PReDICT study, we found that the rate of relapse or recurrence among 94 patients who achieved remission with phase 1 monotherapy was 15.5%, with no difference between the treatment arms (

32). This rate is only marginally lower than the overall 20% rate observed in the present study among patients who responded after combination treatment, although phase 2 patients who achieved remission relapsed half as often (14%) as those who responded to treatment but did not achieve remission (30%). These data reinforce the importance of remission as an important goal for long-term outcomes and indicate that patients who require combination treatment to achieve remission are about as likely to remain free of recurrence during 2 years of follow-up as patients who achieve remission with a monotherapy.

In the present study, we found that pretreatment anxiety predicted lower probability of remission for patients receiving either the CBT plus medication or the medication plus CBT combination. Substantial evidence indicates that the presence of comorbid anxiety disorders and higher anxiety rating scale scores predict poorer outcomes with pharmacotherapy (

37,

38), although negative findings also have been reported (

49,

50). In contrast, several studies have failed to find an impact of anxiety on acute outcomes with CBT treatment for depression (

18,

51), although one large study had mixed findings (

52). The recent Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments depression guidelines assert that insufficient evidence exists to support a predictive effect of anxiety symptoms or disorders on psychotherapy treatment outcomes for depression (

53). Anxiety was not found to moderate outcomes in trials comparing patients randomly assigned to receive CBT and an antidepressant medication (

18,

54), although a recent analysis of three trials found that for chronically depressed patients with high levels of both depression and anxiety, CBASP was less effective than antidepressant medication, which in turn was less effective than the combination of the two treatments (

55). In contrast, patients with moderate depression and low anxiety did better with the psychotherapy than with medication (

55). In one of the few studies of the impact of anxiety on depression recurrence after CBT treatment, Fournier and colleagues found that patients with anxiety at baseline relapsed sooner than patients without anxiety at baseline (

18). However, the effect of anxiety did not differ between the CBT and medication treatment groups. Taken together, these results suggest that the presence of anxiety is a negative predictor of acute treatment outcomes for major depression, although its role as a moderator remains unclear.

An additional finding of interest was that although depression severity (as measured by HAM-D score) was a predictor of improvement, depression severity no longer predicted outcomes after controlling for level of anxiety. Conversely, the negative predictive value of anxiety on outcomes persisted even after controlling for the effect of depression on anxiety scores. These results suggest that previous studies that identified depression severity as a negative predictor of outcome should be reanalyzed to examine whether the results persist after controlling for anxiety.

Although it is possible that discontinuation symptoms after stopping an SSRI (

56) or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (

57) may be mistaken for a depressive relapse (

58), our data were not affected by this possibility. Of the 16 patients who experienced recurrence of depression during the follow-up phase, only three had discontinued the medication: one recurrence occurred 3 weeks after the last dose; the other two occurred ≥8 months later. These data are similar to those observed with the patients who achieved remission with medication alone during phase 1; in that phase, of the 20 patients who achieved remission and discontinued medication during follow-up, three experienced recurrence; all three recurrences occurred ≥6 months after the last dose (

32).

A notable result was that 90.3% (112/124) of the patients who had not achieved remission at the end of phase 1 accepted entry into phase 2. Furthermore, the completion rate of patients entering phase 2 was 86%, with negligible differences between treatment arms in phase 2. These high rates may have stemmed from the requirement for study entry that patients be willing to be assigned to medication or psychotherapy treatment and from the trust built with the treatment team during phase 1. Clinicians should remain mindful of the utility evidence-based psychotherapies can provide to patients who do not achieve remission with an antidepressant and vice versa.

The generalizability of these results is limited. First, none of the enrolled patients had previously received an evidence-based treatment for depression, and comorbid conditions were limited; it is likely that response and remission rates would be lower among patients with additional comorbid conditions and prior treatment histories. On the other hand, the medication dosages were capped at the maximum recommended by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for major depression, and thus were below those often used in clinical practice, which may have limited the number of patients who achieved remission with medication. Second, the patients enrolled in PReDICT were considered by the study psychiatrist to have major depressive disorder as their primary diagnosis requiring treatment. In clinical practice, patients with major depression may have an anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder that is deemed more significant than the depression. In such cases, the outcomes from combination treatments may differ. In addition, although the effect size of adding antidepressant medication for patients responding to CBT but not achieving remission was large, the number of patients in this subgroup was small. Without a control condition, we cannot exclude the possibility that much of the patients’ improvements in phase 2 were simply due to the passage of time while in treatment. PReDICT excluded individuals who were actively suicidal or had depression with psychotic features, for whom the order effects and overall efficacy of treatment combinations may differ. Finally, in phase 2, patients who received CBT initially received only monthly booster sessions of CBT along with medication; this intensity of CBT in phase 2 may have been less than what would be necessary to see the full effects of combination treatment in these patients.

Our results indicate that CBT and pharmacotherapy are roughly equally efficacious for achieving remission when sequentially combined for patients who do not respond or do not achieve remission with a single-modality treatment. The only similar published trial we are aware of, which evaluated the sequential addition of psychodynamic psychotherapy or antidepressant medication after poor response to single-modality treatment in 29 patients, also found that both treatment combinations were effective (

17). Thus, both studies support the conclusions of a recent meta-analysis of combination treatments that the effects of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy on depression are largely independent (

59). Taken together, the existing data support the rationale for combining treatments with differing mechanisms of action, and differing efficacy as indicated by patients’ brain activity patterns (

21,

60,

61), to optimize treatment outcomes. The sequential combination of CBT or antidepressant medication for patients who do not achieve remission with monotherapy is an effective approach for outpatients with major depression, and the sequence in which the treatments are applied does not appear to affect end-of-treatment outcomes.