Initial examination of the biological correlates of parental Holocaust trauma focused on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and on two genes related to glucocorticoid signaling:

NR3C1, encoding the glucocorticoid receptor, and FK506 binding protein 5 (

FKBP5), encoding a glucocorticoid receptor co-chaperone that has been shown to be altered in PTSD (

4,

5). The HPA axis is subject to early developmental programming, including via epigenetic alterations to

FKBP5 and

NR3C1 (

6,

7). Changes in DNA methylation of the

NR3C1 promoter, glucocorticoid receptor responsiveness, and ambient cortisol levels have been demonstrated in offspring of Holocaust survivors in relation to parental sex and PTSD (

8), prompting a preliminary study examining DNA methylation on a region of the

FKBP5 gene containing functional glucocorticoid response elements (

5). The FKBP5 protein moderates translocation of the bound glucocorticoid receptor and is a regulator of glucocorticoid receptor responsivity (

7,

9).

FKBP5 was identified in the first genome-wide transcriptomics study of PTSD as one of several mRNAs that distinguished trauma-exposed persons with and without PTSD, independent of

FKBP5 genotype (

10). Functional epigenetic alterations to

FKBP5 have been observed in association with psychiatric vulnerability, resilience, and symptom improvement in PTSD (

7,

9,

11). Increased methylation at

FKBP5 intron 7, specifically at CpG site 6, was observed in Holocaust survivors, but lower methylation at this site was seen in their offspring compared with respective control subjects (

5).

Results

Descriptive Demographic and Clinical Findings

Demographic and clinical characteristics are detailed in

Table 1. Offspring sought psychiatric care and were taking psychotropic medication(s) more often, demonstrated more anxiety disorders and PTSD, self-reported higher symptom severity, and showed lower parental bonding scores than control subjects.

Characteristics of parental Holocaust exposure and PTSD.

Holocaust exposure was reported for both parents by 75.5% (N=111) of offspring; 15.6% (N=23) had paternal exposure only, and 8.8% (N=13) had maternal exposure only. Maternal and paternal PTSD were reported by 54.5% (N=79) and 41.4% (N=60) of Holocaust offspring, respectively, with 37.7% (N=55) reporting one parent with PTSD and 29% (N=42) reporting PTSD for both parents.

Mean age at the beginning of the Holocaust was 15.0 years (SD=7.8) for mothers and 19.9 years (SD=8.6) for fathers. A total of 19.7% (N=29) of Holocaust offspring were born to mothers who were ≤11 years old at the start of the Holocaust, and 16.3% (N=24) had fathers who were ≤11 years old at the start of the Holocaust. Comparing childhood with later parental exposure yielded no significant difference in the frequency of maternal (58.6% and 66.7%, respectively) or paternal (45.8% and 44.4%, respectively) PTSD (χ2=0.619, df=1, n.s., and χ2=0.015, df=1, n.s., respectively).

FKBP5 Intron 7, Site 6 Methylation in Holocaust Offspring and Control Subjects

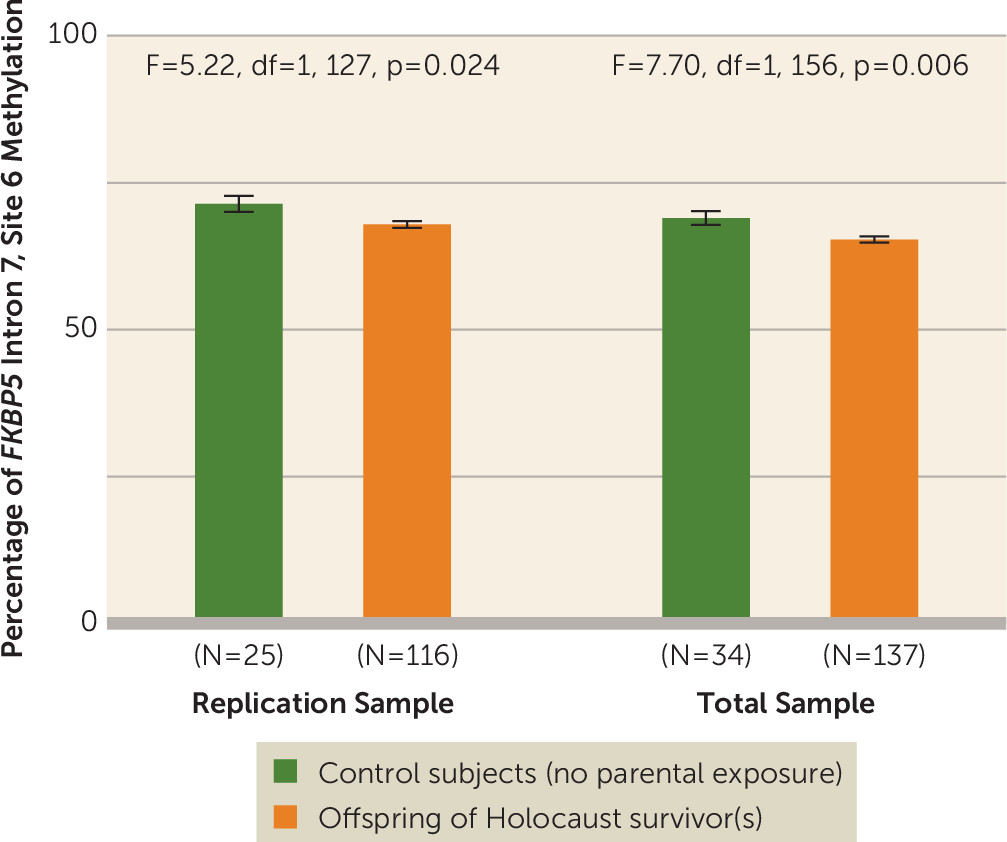

The percentage of

FKBP5 site 6 methylation was lower in Holocaust offspring (mean=67.12%, SE=0.53) than in control subjects (mean=69.64%, SE=1.09) (F=4.26, df=1, 150, p=0.041, pη

2=0.028) for the replication sample, and for the entire sample (offspring: mean=64.87%, SE=0.48; control subjects: mean=67.49%, SE=0.93; F=6.26, df=1, 180, p=0.013, pη

2=0.034). Including covariates in the expanded model strengthened this difference (F=7.70, df=1, 156, p=0.006, pη

2=0.048) (

Figure 1).

Because offspring sex was a significant covariate in the above analysis, a two-way ANCOVA was performed. There were significant effects of sex (male: mean=63.06%, SE=0.84; female: mean=67.62%, SE=0.69; F=16.80, df=1, 179, p<0.0005) and group (control subjects: mean=66.7%, SE=0.93; offspring: mean=63.94%, SE=0.52; F=6.92, df=1, 179, p=0.009), but the absence of a significant interaction between the two (F=0.96, df=1, 179, n.s.) indicates that sex did not account for the reduction in FKBP5 methylation observed in Holocaust offspring.

Table S1 in the online supplement details group comparisons for additional FKBP5 sites on intron 7 to highlight the specificity of the effect of parental Holocaust exposure at site 6 and to demonstrate that mean intron methylation was also reduced. The intercorrelations among sites presented in Table S2 in the online supplement indicate that site 6 is part of a functional unit with other sites on intron 7. There was no difference in site 6 methylation by genotype (protective allele: mean=65.01%, SE=0.61; risk allele: mean=65.74%, SE=0.65; F=0.65, df=1, 176, n.s.).

FKBP5 Gene Methylation and Offspring Symptom Profiles

Lower site 6 methylation was significantly associated with reduced anxiety (r=0.169, df=167, p=0.028) but not with childhood trauma (r=0.130, df=171, n.s.), parental bonding (maternal: r=0.027, df=166, n.s.; paternal: r=0.115, df=162, n.s.), depression severity (r=0.000, df=173, n.s.), or PTSD severity (current: r=0.090, df=169, n.s.; lifetime: r=0.083, df=169, n.s.).

Effect of Sex of Holocaust-Exposed Parent

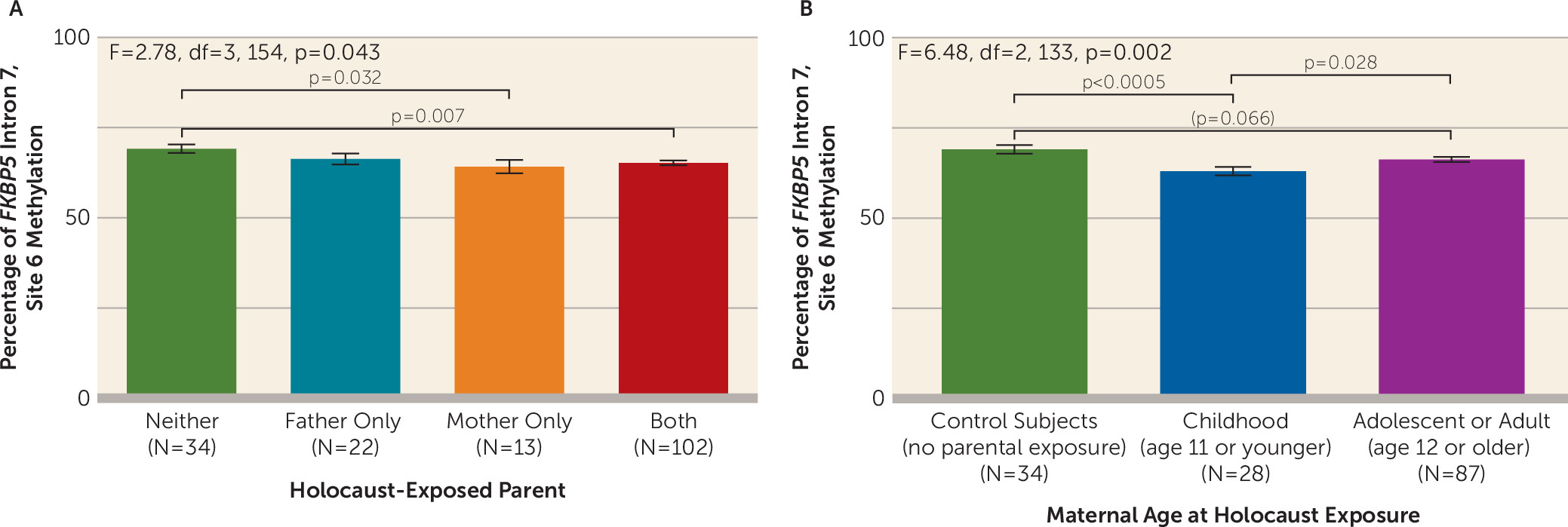

Maternal exposure was associated with lower site 6 methylation (F=2.78, df=3, 154, p=0.043), but methylation for paternal exposure did not differ significantly from that of control subjects (

Figure 2A).

Effects of Maternal or Paternal PTSD

There were no significant site 6 methylation differences in association with maternal or paternal PTSD (maternal PTSD: F=0.26, df=1, 156, n.s.; paternal PTSD: F=0.35, df=1, 156, n.s.; or with the interaction between maternal PTSD and paternal PTSD: F=0.43, df=1, 156, n.s.).

Effects of Maternal Childhood Holocaust Exposure on FKBP5 Methylation

As shown in

Figure 2B, significantly lower site 6 methylation was observed in offspring whose mothers were exposed in childhood compared with control subjects (p<0.0005) and compared with offspring of mothers exposed later in life (p=0.028), although the latter group did not differ significantly from control subjects (p=0.066) (F=6.48, df=2, 133, p=0.002; pη

2=0.089). When accounting additionally for paternal age at Holocaust exposure, the finding remained significant (F=6.78, df=1, 114, p=0.010). However, an apparent effect of paternal age at exposure on site 6 methylation (F=4.01, df=2, 142, p=0.020) was no longer significant when also accounting for maternal age at exposure (F=0.55, df=1, 107, n.s.).

As shown in

Table 2, clinical measures that distinguished Holocaust offspring from control subjects were largely associated with older maternal age at exposure. Generally, offspring with childhood maternal Holocaust exposure did not differ significantly from control subjects or from offspring born to mothers with later exposure.

FKBP5 mRNA Expression

FKBP5 gene expression, available only for participants in study 2, was higher in Holocaust offspring than in control subjects (control subjects: mean=0.78, SE=0.15; Holocaust offspring: mean=1.13, SE=0.06; F=6.82, df=1, 84, p=0.011). The effect was maintained when controlling additionally for genotype (F=6.41, df=1, 80, p=0.013) but was no longer significant using the expanded model (F=2.89, df=1, 73, p=0.093), a difference likely reflecting an effect of lifetime anxiety disorder, the only significant covariate in the latter analysis (F=14.18, df=1, 73, p<0.0005). Indeed, FKBP5 expression was positively correlated with self-reported anxiety ratings (r=0.246, df=81, p=0.025) and was higher among those with (mean=1.27, SE=0.08) relative to those without (mean=0.84, SE=0.09) lifetime (F=16.12, df=1, 83, p<0.0005) or current (F=12.77, df=1, 83, p=0.001) anxiety disorders. There was no significant association between basal (i.e., unstimulated) FKBP5 gene expression and site 6 methylation (r=−0.003, df=83, n.s.).

Relationship of FKBP5 Methylation to Neuroendocrine Measures

As shown in

Table 3, site 6 and mean intron 7 methylation (sites 3–6) were negatively correlated with basal cortisol levels (r=−0.308, df=100, p=0.002, and r=−0.364, df=100, p<0.0005, respectively), with cortisol decline following 0.50 mg of oral dexamethasone (r=−0.287, df=93, p=0.005, and r=−0.344, df=93, p=0.001), and with weaker glucocorticoid sensitivity as determined by the lymphocyte lysozyme IC

50-DEX (r=0.220, df=98, p=0.028, and r=0.332, df=98, p=0.001).

Table 3 also details associations between

FKBP5 methylation, expression, endocrine markers, and previously reported glucocorticoid receptor (

NR3C1) 1F promoter methylation and gene expression (

4).

FKBP5 intron 7 and glucocorticoid receptor 1F promoter methylation were not significantly correlated; however, each was associated with distinct, but also overlapping, neuroendocrine measures.

Discussion

The results reported here replicate the previous observation of reduced methylation at a CpG site in an intronic enhancer of the

FKBP5 gene in adult offspring of Holocaust survivors (

5). Replication of this finding in offspring studied years apart, using DNA extracted from whole blood and peripheral blood mononuclear cells, with the use of similar pyrosequencing methods across three laboratories, increases confidence in the finding. Offspring age, childhood trauma severity, psychiatric diagnoses, suicidality, parental PTSD, psychotropic medication,

FKBP5 genotype, or differential immune cell count did not account for the decrement in site 6 methylation. Rather, reduced

FKBP5 methylation was associated with maternal Holocaust exposure and was particularly evident in offspring of mothers exposed as children. While the effect for the comparison between Holocaust offspring and control subjects was modest, the effect comparing offspring with maternal childhood exposure and control subjects was large.

An effect in a single area on a functionally relevant gene in peripheral blood may serve as a sentinel for significant functional effects, particularly if the observed change is reliable and correlated with changes in methylation of that gene in other important target tissues. The present finding builds on translational work demonstrating correlations of glucocorticoid-induced changes in

FKBP5 enhancer methylation between rodent peripheral blood and hippocampus (

22). In human tissue, DNA methylation of intron 7, site 6 was shown to be affected by glucocorticoids in peripheral blood cells and in a multipotent hippocampal progenitor cell line (

7). Stable DNA demethylation of

FKBP5 intron 7 in response to glucocorticoids in human hippocampal cells was present during early but not later phases of cellular proliferation and differentiation (

7). In these models,

FKBP5 intron 7 methylation was correlated with glucocorticoid-induced

FKBP5 expression and glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity as determined in an ex vivo lymphocyte model (similar to results shown in

Table 3), demonstrating the functional relevance of a methylation change in this intronic region;

FKBP5 methylation was not, however, correlated with basal mRNA expression, as shown in this study and described elsewhere (

23).

When bound to the glucocorticoid receptor protein complex,

FKBP5 reduces ligand binding, nuclear translocation, and functional sensitivity of the glucocorticoid receptor (

7,

9). The significant correlations of

FKBP5 methylation in peripheral blood with endocrine measures imply that small effects observed in blood cells may reflect functionally significant alterations in other stress responsive systems. Moreover, small differences in intron 7 DNA methylation in peripheral blood have been associated with structural and functional brain alterations (

7,

24). Methylation at CpG sites within the glucocorticoid response elements of intron 7 was intercorrelated and likely functions as a unit—with site 6 best representing the unit—a finding previously demonstrated in a reporter gene assay (

7). Indeed, correlations between endocrine measures and mean methylation of the intron were more robust than those with site 6 methylation.

In the present study, as in the pilot (

5), the effect of maternal Holocaust exposure on site 6 methylation was independent of genotype and was not associated with trauma-related psychopathology. Rather, lower site 6 methylation was associated with diminished self-reported anxiety symptoms, suggesting the possibility of a protective effect. Offspring of mothers exposed in childhood showed the greatest reductions in methylation but also the least psychopathology. Reduced intronic and site 6 methylation in offspring contrasts with increased site 6 methylation observed in Holocaust survivors (although, interestingly, parental and offspring methylation at site 6 were positively correlated) (

5).

FKBP5 intron 7 methylation was not correlated with methylation of the

NR3C1 gene, although both were associated with slightly different HPA axis measures, suggesting that methylation in genes that are known to interact may be independently regulated and associated with distinct aspects of trauma exposure or its sequelae (

25). For instance, past work has shown that glucocorticoid receptor 1F promoter methylation predicted response to psychotherapy for PTSD, while posttreatment

FKBP5 promoter methylation was associated with treatment-induced symptom change (

11). Moreover, glucocorticoid receptor methylation has been shown to be differentially associated with maternal and paternal PTSD, a finding linked with increased trait anxiety, depression, and risk for PTSD (

4).

Within

FKBP5 intron 7, different CpG sites appear to be subject to distinct influences, as indicated by the lack of association between site 6 methylation and childhood trauma, whereas methylation of other intron 7 sites (particularly site 3) has been shown in this and other studies (

5,

7,

24,

26) to interact with the rs1360780 genotype to increase risk for the development of PTSD in the presence of childhood trauma. Only one single-nucleotide polymorphism was measured in the present investigation; however, other genetic influences on site 6 methylation may be detected in future studies using genome-wide approaches. That

NR3C1 and

FKBP5 methylation relate to distinct clinical correlates suggests a complex interaction between the two systems that could be further explored to better understand sources of variation in molecular and endocrine phenotypes.

The finding of decreased

FKBP5 methylation with earlier maternal age at Holocaust exposure is consistent with a previous observation that maternal age at exposure and PTSD were independently associated with reduced urinary cortisol levels in adult offspring (

27). Offspring born to mothers with childhood exposure showed elevated 11-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11-β-HSD-2) activity (

28), a finding directionally opposite to that in Holocaust survivors (

29). Survivors who were younger at age at exposure demonstrated the lowest 11-β-HSD-2 enzyme activity (

29), but their adult children had the highest levels of urinary 11-β-HSD-2 activity (

28). Interestingly, methylation of both

FKBP5 and

HSD11B2 is regulated in the placenta to moderate embryonic exposure to maternal glucocorticoids (

6).

A maternal effect may be attributable to in utero glucocorticoid exposure (

2,

30–

32) and reflect preconception molecular effects on gametes or altered placental neuroendocrine stress physiology, with effects on fetal brain development in association with maternal childhood adversity (

30,

33). Theoretically, trauma occurring prior to puberty may precipitate changes to the oocyte that are maintained throughout embryogenesis and/or are reestablished after conception, potentially influencing the intrauterine environment (

2,

34). Before puberty, oocytes are still in a haploid demethylated state and are vulnerable to environmental perturbations (

35). However, we know of no studies that have examined the possibility of epigenetic transmission through oocytes in humans or animals. That early maternal age at trauma exposure is a significant determinant of an intergenerational effect on site 6 (and intron 7) methylation may also imply a differential effect on subsequent interpersonal interactions between mother and child, including parental bonding and attachment (

36). It is reasonable to infer that maternal age at exposure may have influenced child-rearing practices, a possibility suggested by the finding of reduced psychopathology among offspring raised by mothers exposed in childhood. Moreover, parental care and overprotection ratings differed from control subjects only for offspring whose mothers were exposed later in life. These data underscore the complexity of assigning specific mechanisms for the observed effects, because even if an epigenetic alteration involves a postconception change to germ cells or in utero perturbations, the impact of child rearing, attachment, and other postnatal environmental characteristics may be the more important drivers of change.

The lack of a finding specific to paternal exposure should not be interpreted to reflect a lack of epigenetic effects of paternal trauma. Indeed, several animal and human studies suggest that there are potent effects on offspring transmitted through sperm (

26,

31,

34). It is also not possible to know, when both parents have been exposed to severe trauma at slightly different ages, what the synergistic effects of that exposure might be on their offspring.

Data from the present cross-sectional study in adult offspring cannot speak to the mechanisms through which epigenetic alterations may have been acquired. It is nonetheless interesting to speculate whether the findings help explain increased offspring vulnerability to psychopathology or reflect an adaptation to optimize offspring preparedness or response to adversity in their own lives (

37). Disinhibited

FKBP5 expression might promote caution or vigilance in an adverse environment, behaviors elicited by increased

FKBP5 expression in animal experiments (

38). Consistent with these behaviors, reduced methylation of

FKBP5 intron 7 was associated with diminished anxiety following exposure-based psychotherapy (

39). The significant associations of increased anxiety with higher

FKBP5 mRNA levels, and of decreased anxiety with lowered

FKBP5 methylation, would be consistent with such adaptive effects. The observation that lower site 6 and mean intron 7

FKBP5 methylation was associated with reduced glucocorticoid sensitivity and increased basal cortisol levels suggests that individuals with lower

FKBP5 methylation display fewer PTSD-like endocrine alterations, which have been associated with elevated risk for psychopathology (

8,

27). Certainly, genome-wide studies may identify broader functional epigenetic and transcriptomic profiles associated with intergenerational trauma and risk or resilience in offspring, and they would provide an important context for the present findings.

The potential functional role of any single observed epigenetic alteration requires further study, and the regulation of any specific gene transcript requires knowledge of other genes, epigenetic marks, microRNAs, and additional regulators. This study is limited by the lack of genome-wide data, the single cross-sectional observation, and the uneven sample sizes for the Holocaust offspring and comparison groups. A further limitation is that although a strong signal was detected for maternal childhood exposure, the number of participants with only fathers exposed may have been too small to test the contribution of the paternal germline to the present findings.

Nonetheless, the previous observation of an association of parental Holocaust exposure with

FKBP5 DNA methylation in adult offspring has been replicated in a larger cohort. Previous work is extended by the new observation that effects on offspring

FKBP5 intron 7 methylation and

FKBP5 gene expression are associated with maternal exposure and, for the former, with maternal childhood trauma exposure. Our study cannot distinguish determinants of the observed effects, including a preconception effect on germ cells, differences in the in utero milieu, alterations in postnatal care, or other influences (

3,

32). However, the relative stability of the observation across cohorts, in adults born years or sometimes decades after parental exposure, provides an impetus for basic science studies in this field. Prospective intergenerational studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms for such trauma effects, as well as their functional consequences for vulnerability, adaptation, and resilience.