Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is currently considered an early-onset neurodevelopmental condition characterized by social communication impairments and repetitive, restrictive behaviors (

1). Although defined categorically for clinical purposes, its genetic architecture and epidemiological profile suggest that ASD lies at the end of a continuously distributed continuum (

2–

4). It is well established that childhood ASD shows a very high degree of phenotypic and etiological heterogeneity (

5), which includes marked variation in both its short-term developmental trajectories (

6,

7) and its later clinical course (

8).

Follow-up studies of clinic-ascertained autism into adulthood suggest that autistic symptoms typically decline with age (

9), although one school-ascertained study observed little symptom improvement (

10), and broader, global outcomes for ASD are highly variable (

11,

12). To date, virtually all follow-up studies into adulthood have been conducted in patients referred to clinic during childhood, which precludes the study of individuals who may not present with high symptom levels until adolescence or adulthood. Adolescence and early adulthood represent a time of heightened social challenges that include establishing romantic partnerships, transitioning to employment, and managing independent living. One population-based study that followed individuals to age 17 (

13) observed an increase in social communication symptoms among females in adolescence, a finding that appears to be at odds with much of the clinical literature. However, there is growing appreciation that some affected individuals, especially females, may present in clinic with autistic symptoms in adolescence, later, or not at all by “camouflaging” or compensating for their difficulties (

14).

Thus, findings on the natural history of autistic symptoms are mixed, and they are not examined in nonclinical cohorts followed to adulthood. The aim of this study was to characterize the development and heterogeneity of autistic symptoms in a U.K. population-based cohort from childhood to age 25 using the same measure and rater across time. Typically, measures and raters change from adolescence to adult life, precluding the opportunity to reliably examine developmental trajectories. We used a latent variable approach to investigate autistic symptom developmental trajectories, and we tested the validity of these trajectories by examining associations with established measures of child and adult ASD, child IQ, communication problems, peer problems, and adult functioning.

Discussion

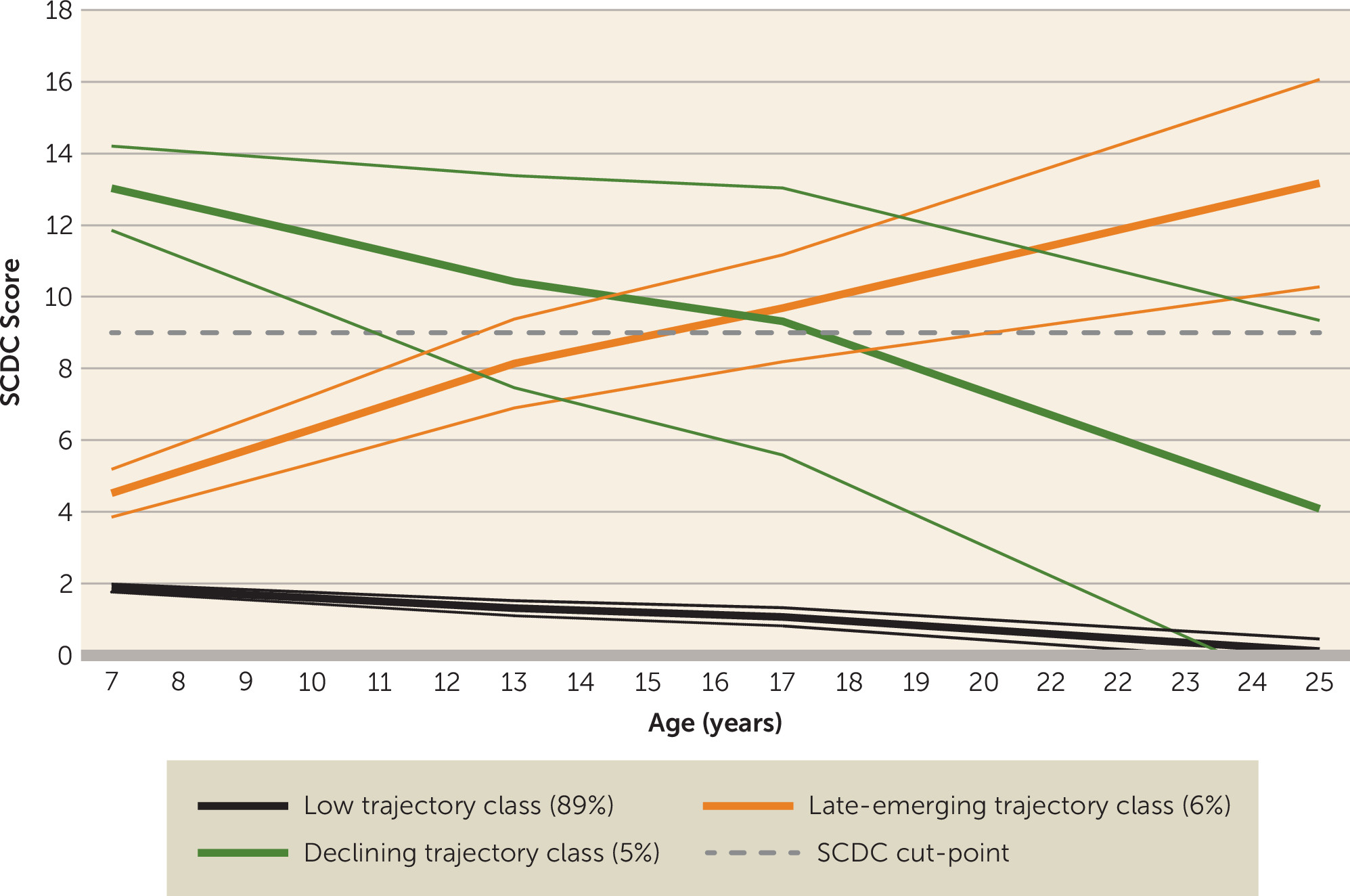

Our aim in this study was to characterize the natural history and heterogeneity of autistic symptoms in a U.K. population-based cohort from childhood to age 25. Using repeated measures of parent-rated social communication problems, we identified three distinct trajectories spanning childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. Most of the sample belonged to a persistently low symptom trajectory group, as would be expected in a population-based cohort. In line with much of the clinical literature, another group showed high autistic symptoms in childhood that declined over time. However, we also detected a third, “late-emerging” trajectory group who showed initially low ASD symptom levels in childhood that increased across adolescence and into young adulthood. Previous work in ALSPAC has found an increase in ASD symptoms across adolescence, particularly for females (

13); our work differs in that we investigated distinct developmental trajectories of ASD symptoms into young adulthood, identifying both declining and late-emerging symptom trajectory groups. Furthermore, we examined associations with other measures in childhood and adulthood to investigate these different developmental patterns.

The declining symptom trajectory class showed associations with various features that typify ASD diagnosis, including male sex, low IQ, and communication and peer problems. Sensitivity analyses using a more detailed autism measure at age 25 suggested that while social interaction/behaviors somewhat improved into adulthood for this group, attention to detail remained. Also, despite the attenuation of social communication problems in the declining trajectory class from childhood to adulthood, this group still showed elevated levels of distress and impairment in adulthood and were more likely not to be in education, employment, or training at age 25 compared with the low-symptom group. This is consistent with previous longitudinal research on clinical cohorts, which has shown that ASD symptoms tend to decline with age but that outcomes vary, and impairment often persists (

9–

11).

The late-emerging ASD symptom trajectory class is unexpected given that ASD is defined as a childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorder. This late-emerging group showed (elevated) levels of adult impairment similar to those of the declining ASD class in terms of not being in education, employment, or training and reported distress and impairment, as rated by both parents and the individuals themselves. However, they did not show the male preponderance that is typical of ASD. Interestingly, late-onset symptoms have been a growing controversy in relation to another childhood neurodevelopmental disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (

41). However, unlike ADHD, where later onset has not been found to be associated with childhood neurodevelopmental problems, the late-emerging ASD group, at least in this cohort, do not appear to have entirely newly emerging neurodevelopmental difficulties. In childhood, the late-emerging ASD group displayed some neurodevelopmental impairment, including an elevated level of a broader range of ASD traits, pragmatic language problems, and peer problems, compared with the low-symptom group. It is also noteworthy that while ASD symptoms were relatively low in childhood, they were somewhat elevated compared with the low trajectory class (see

Figure 2). Thus, it may be that ASD symptoms were “camouflaged” in childhood for this group, perhaps as a result of accommodating environments, scaffolding by families, or individual characteristics that enabled them to compensate during this developmental period, but that with increasing demands on social skills with age, social difficulties became more apparent (

14). Interestingly, while some work has suggested that compensation or camouflaging may be particularly apparent in females (

14), we did not observe a female preponderance in this group (although we also did not observe the “typical” ASD male preponderance).

The timing of the emergence of ASD symptoms in adolescence is also supported by sensitivity analyses using a task-based index of ASD measuring theory of mind at age 13, which suggested that the late-emerging group had intermediate scores between the low and declining groups at this age. Previous explanations as to why ASD is detected later (in childhood) despite earlier assessments include early symptoms being missed or overshadowed by other difficulties, “overdiagnosis” of later symptoms, or a genuinely later symptom onset (

42). Our use of a population-based cohort makes misdiagnosis and overdiagnosis unlikely. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that ASD symptoms had previously been overshadowed or that late reported symptoms actually index another form of psychopathology. For example, post hoc analyses found the late-emerging trajectory group to have elevated emotional problems in young adulthood (results available on request), suggesting that the emerging symptoms identified in this group may reflect internalizing problems. Alternative study designs are needed to infer whether these adult emotional problems are a secondary consequence of the late ASD symptoms or whether some of the late-reported ASD symptoms are indexing emotional problems. We also cannot rule out the contribution of measurement error. Alternatively, it is possible that ASD symptoms genuinely show a much more variable age at first manifestation, at least in the general population, than previously realized.

While many of our measures were parent-rated, enabling consistency of rater and of measures across development, the inclusion of adult self-reports provided additional insights. By age 25, although parents reported that ASD-related difficulties and peer problems were higher in the late-emerging than the declining trajectory class (defined using parent reports), self-rated ASD-related problems and impairments were similar for each of these groups; thus, the observed symptom decline for those with high childhood symptom levels could be influenced by rater effects. One explanation is that by adulthood, individuals have better insight than their parents into some of their own social behavior and interaction–related ASD symptoms. Another possibility is that parents endorse autistic symptoms in their adult offspring more readily when impairment is present: we observed that although the rate of self-rated high risk for ASD was similar in the late-emerging and declining trajectory groups, self-reported distress and impairment was higher in the late-emerging class. Regardless, it seems that later-emerging ASD is problematic in adulthood across a variety of measures and raters.

An important consideration in interpreting the results is whether the meaning of autistic items captured by the same measure (in this study, the SCDC) changes with age. There are many challenges to adopting a developmental perspective in research, one of which is that measures and informants typically change from childhood to adulthood (

43). However, identical questions (e.g., “does not appear to understand how to behave when out”) may capture different impairments at different ages. The SCDC is also yet to be validated in adulthood, although our analyses suggested acceptable measurement invariance across the ages we assessed, and we previously reported that the adult and child SCDC show similar patterns of association with genetic risk scores (

21).

Our study must be considered in light of its limitations. Like many longitudinal samples, ALSPAC suffers from nonrandom attrition, whereby individuals at elevated risk of psychopathology are more likely to drop out of the study (

44)—approximately 54% of the original ALSPAC birth cohort were included in our age-25 analyses—which may have led to an underestimation of the number of individuals in high symptom trajectories. However, we used a range of statistical methods to assess the effect of missingness and found a similar pattern of results. Our trajectories were also based on a measure of social communication and did not include the repetitive behaviors and restricted interests domains of autism; although this measure has previously been validated against childhood ASD diagnosis in ALSPAC (

20), these domains may show a different natural history (

45). Also, we could not examine trajectories of self-rated symptoms, as these were only available in adult life. The use of a population sample (and the size of the sample) is also likely to have affected the trajectory classes that we detected. In particular, our model did not include a class with high childhood symptoms that persisted into adulthood, which would be expected in clinical samples (

9). In model-fitting, a four-class solution did include a high-persistent trajectory, but this was a small class (1.8%), the inclusion of which did not improve model fit. Post hoc analyses comparing this model to our three-class solution found that the majority of those who would have been included in the high-persistent class were included in our declining class (approximately 72%, with the remainder in the late-emerging class); thus, our declining class likely includes a small proportion of individuals for whom symptoms persist into adulthood (reflected in the large confidence intervals for this group). This small “fourth” class shows a prevalence rate similar to the reported population prevalence of 1% for adult ASD (

46,

47). Studies using high-risk, clinical, or larger general-population samples would be better placed to characterize differences between ASD symptoms that persist compared with desisting or increasing across development in individuals with a diagnosis. However, such samples may not be the ideal ones for detecting later-emerging problems.

In summary, we observed heterogeneity in the natural history of autistic symptoms in the general population. We found that for individuals with elevated symptoms in childhood, symptom levels tended to decline into young adulthood. Intriguingly, we also identified a group for whom autistic symptoms emerged later, across adolescence and adulthood, but who showed evidence of earlier neurodevelopmental impairment, including low IQ and language problems in childhood. Both groups showed elevated levels of distress and impairment in young adulthood. These findings support the continued monitoring of ASD symptoms and associated impairment across development. They also challenge our current understanding that ASD symptoms invariably manifest early in development. This requires further investigation, as the age at ASD symptom manifestation may be much more variable than previously realized.