The United States Controlled Substances Act of 1970 (CSA) designates many psychedelics as Schedule I substances, establishing federal restrictions and penalties for their manufacturing, distribution, and use (

1). While these psychedelics remain highly controlled under federal law, several city and state governments in the United States have liberalized psychedelic regulations (

2). These liberalized policies vary, from decriminalization of naturally-occurring psychedelics in Oakland, California, to state-regulated use of psychedelic “natural medicine” in Colorado. Reform efforts are ongoing, resulting in an array of heterogenous regulatory policies throughout the country (

3).

The healthcare community may consider these regulatory changes premature, as reflected in the American Psychiatric Association’s position that, “there is currently inadequate scientific evidence for endorsing the use of psychedelics to treat any psychiatric disorder except within the context of approved investigational studies” (

4). As psychedelic use in the United States expands beyond settings that strictly adhere to the regulations of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), communities may adopt social controls, safety practices, and risk mitigation strategies (

5). Stakeholders, communities, and policymakers need guidance on regulatory considerations for non-medicalized uses of psychedelics and potential risk reduction practices for settings where psychedelic use occurs outside of the parameters of the federal CSA.

Psychedelic regulatory options should be informed by empirical evidence of risk and benefit beyond those typically found in new drug applications. Regulating real world psychedelic use outside of conventional clinical settings requires a critical appraisal of the form and function of these uses beyond binary comparisons (e.g., “regulated versus unregulated,” or “therapeutic versus recreational”). Despite the merit of using binary categories such as “medical versus wellness” for preliminary comparisons of policy options (

6), a more nuanced taxonomy of psychedelic uses is warranted.

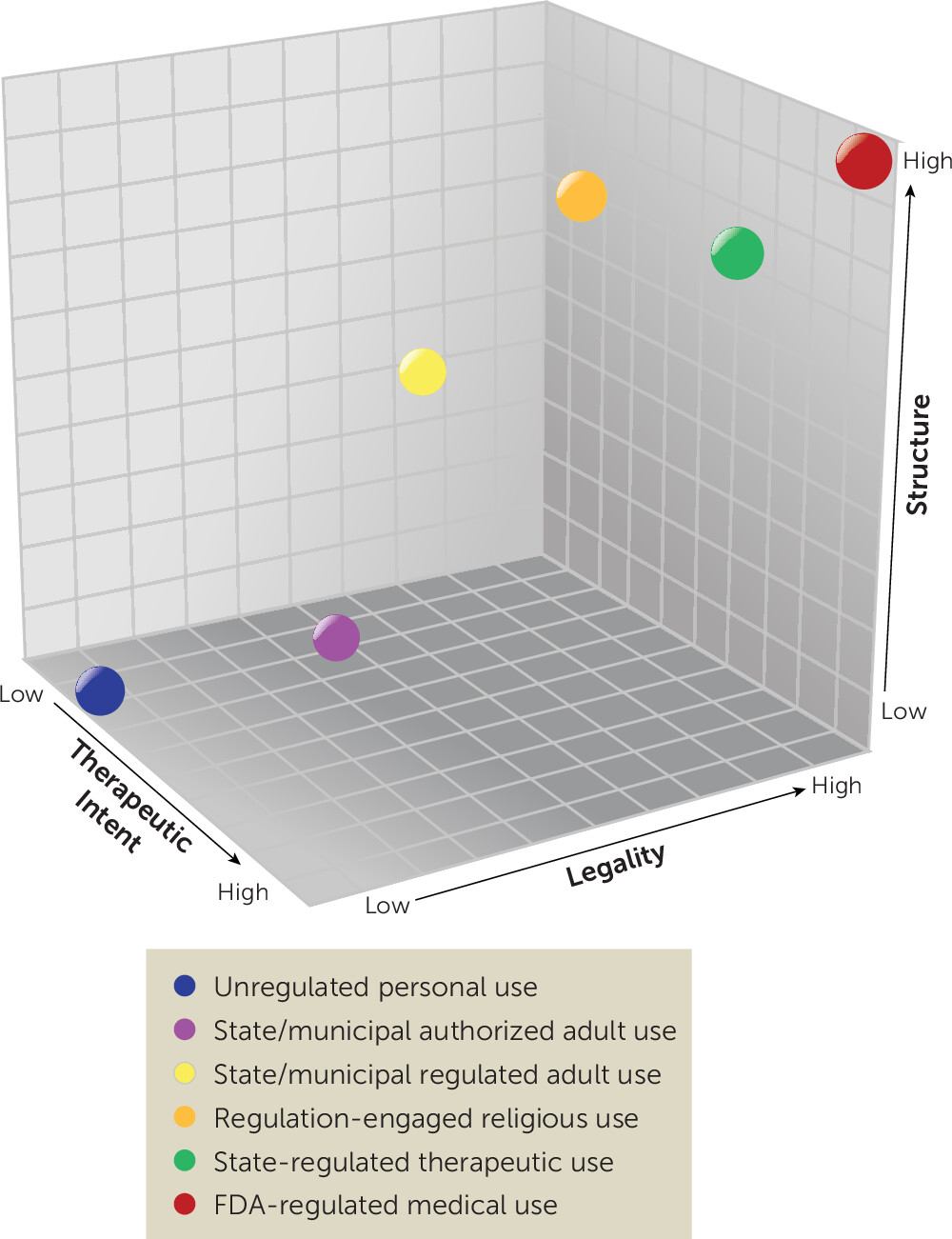

We propose a framework for characterizing psychedelic uses by three key, continuous variables: legality, therapeutic intention, and structure (

Figure 1). These factors, identified as priority areas in drug policy research (

7) and in the psychedelic field (

8–

10), were selected here to highlight important variation observed across psychedelic regulatory structures that are being debated, legislated, and implemented in the United States today. We introduce this framework and briefly review non-federally regulated policy options to illustrate how this framework may be applied. We propose that this framework could be leveraged to compare outcomes of different psychedelic policies, to better understand the implications of these regulatory options on clinical practice, and to tailor future public health campaigns for informing screening and safety practices across different settings.

Three-Dimensional Framework for Psychedelic Policy Analysis

Legality is a complex dimension that broadly outlines the conditions of production, distribution, and use that can be undertaken with or without penalty. Treating legality as a continuum acknowledges the variability that can be seen in controlled substance policies and their implementation. As Schedule I drugs, the DEA has deemed many psychedelics to have no currently accepted medical use and only a specific set of legal uses (e.g., research [

1,

11]). Nevertheless, some municipalities have directed their law enforcement agencies to deprioritize enforcement of laws prohibiting psychedelics (de facto legalization), while some states have passed laws that allow certain additional uses of psychedelics within their borders (de jure legalization). Though federal law generally preempts conflicting state laws, the 10th Amendment prevents the federal government from commanding states to create laws or to use state officers to enforce federal laws, creating a gray zone of legality when states decide not to criminalize conduct that offends federal law, as is currently the case with cannabis regulation in many states (

12). Ultimately, the de facto legality of psychedelic uses will be informed by legal precedent and the selective enforcement of local, state, and federal statutes.

Therapeutic intention refers to the extent to which a policy frames psychedelic use as intended either for medical intervention (i.e., for the treatment of a diagnosed health condition) or for healing (i.e., ameliorating suffering, including spiritual suffering). For example, FDA-regulated therapies for biomedical diagnoses (e.g., treatment of severe alcohol use disorder) fall on the high end of this spectrum, policies that support use for psycho-spiritual practices focused on ‘aligning energetic imbalances’ or generically ‘healing trauma’ would fall in the middle ranges, while decriminalization or legislation supporting recreational use solely for aesthetics, fun, or to enhance creativity, are on the low end.

Structure refers to the degree of organization guiding psychedelic use within a particular context. This may be developed informally, through social norms, or formally, through explicit rules or systems (e.g., regulatory bodies, screening practices, permissions to administer psychedelics, and established care practices). Structure directly influences both set and setting and therefore likely has significant impacts on the outcomes of the diverse forms of psychedelic use (

9,

10).

A Review of Policy Options for Psychedelic Use

The following examples illustrate how different psychedelic uses fit into these three domains.

FDA-Regulated Medical Use

An increasing body of evidence supports the therapeutic benefit of psychedelics, such as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and psilocybin, for various mental health conditions in conjunction with psychosocial support (

14–

16). An FDA-approved use of psychedelic medicine would be high in legality, therapeutic intention, and structure. The psychedelic would likely remain a controlled substance, but licensed prescribers could provide patients with qualifying diagnoses an approved product in clinical settings, regulated by strict controls for storage and dispensing and accompanied by monitoring for adverse reactions. Though the FDA regulates the interstate commerce of medicines and evaluates the therapeutic application of controlled substances, states have jurisdiction over the practice of medicine within state lines, which may allow for other frameworks discussed below.

State-Regulated Therapeutic Use

In the absence of federal approvals, state-regulated therapeutic use of psychedelics would be moderate in legality and structure, and moderate-to-high in therapeutic intention. Current comprehensive medical cannabis programs are a comparable example, operating outside of FDA and DEA regulation (

13). State-regulated medical cannabis legislation permits medical use for specific qualifying health conditions, prevents state criminalization of use for medical purposes, creates processes for access and distribution (e.g., medical cannabis cards and dispensaries), and allows for various products and modes of use. Such a system could be similarly implemented for psychedelic medicines, including potential requirements regarding qualifying conditions, authorized treatment sites, and facilitation with licensed providers (

17,

18). This policy option may also include non-professional, cooperative models like those seen for “cannabis clubs” in Spain (

19,

20) and California (

21) that self-regulate and prioritize community care. Importantly, while this policy would be legal under individual state laws, federal law remains in effect, meaning federal prosecution is still possible should federal agencies choose to enforce the restriction.

State/Municipal-Regulated Adult Use

States and localities may de jure legalize psychedelics for regulated adult use. One example is the Oregon Psilocybin Services Act which legalizes and regulates psilocybin services via licensing of facilitators, service centers, manufacturers, and laboratories (

22). Like state-regulated therapeutic use, state-regulated adult use is moderate in legality. This model will likely be moderate in therapeutic intention, with a policy framework supporting some users pursuing therapeutic outcomes with others seeking personal growth or other objectives. The Oregon law does not frame psilocybin services as medical (“therapy” is not defined in the statute and a medical diagnosis is not required), however the program is regulated by the Oregon Health Authority. Oregon’s psilocybin services are moderate-to-high in structure, with a regulatory body licensing and regulating manufacture, transport, delivery, sale, and purchase of psilocybin products, but with fewer controls than would be seen in a conventional healthcare setting.

State/Municipal-Authorized Adult Use

States may also decide to liberalize access without accompanying regulation. This will often take the form of de facto legalization, such as in Denver (

23), where the city government has directed law enforcement officers to deprioritize enforcement of psilocybin infractions without changing laws or creating regulatory bodies. A recently vetoed California bill (SB-58) aimed to legalize the personal use of certain psychedelics with minimal accompanying regulation, while also establishing a workgroup to develop recommendations for therapeutic use (

24). Being inconsistent with the CSA, these approaches would be considered low-to-moderate legality; they are also low-to-moderate in therapeutic intention and low in structure.

Regulation-Engaged Religious Use

While the use of psychedelics in religious contexts in the United States is not new, the DEA has granted few exemptions from the CSA on religious grounds (

25). According to federal law, the CSA does not apply to the “nondrug use of peyote in bona fide religious ceremonies of the Native American Church” (NAC) (

26), however

peyoteros who harvest for NAC members require DEA Schedule I registration. Through court orders and an application of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, branches of two Brazilian ayahuasca religions, the União do Vegetal and Santo Daime, have been granted DEA Schedule I registrations permitting practice within the United States (

27).

A more fully developed religious exemption process could support more regulation-engaged religious use. Religious uses with formal CSA exemptions would be high in legality. Religious communities who obtain CSA exemptions are typically moderate-to-high in structure given the scrutiny of sincerity of their beliefs and safety practices by the federal government (

28). Religious communities where psychedelics are explicitly used for spiritual healing will be higher on the dimension of therapeutic intent, even if they do not claim to treat maladies recognized by allopathic medicine.

Unregulated (Non-authorized) Personal/Recreational Use

Unauthorized or “underground” community and individual use (e.g., music festivals) exists outside of federal and state regulation, are low in legality, and often low in therapeutic intention and structure.

Conclusions

The growing interest in psychedelics coupled with municipal and state efforts to liberalize psychedelic regulation prompts consideration of a wide and complex range of potential policy options. Developing a framework for characterizing policies across multiple dimensions can provide a mechanism for analyzing these policies without minimizing their complexity. Here we proposed a three-dimensional framework that contextualizes psychedelic uses by their degree of legality, therapeutic intention, and structure, and briefly reviewed current non-federally regulated policy options and how they can be examined through this framework.

The intention of this framework is to offer a new conceptualization for comparing and discussing the variety of psychedelic regulatory policies. Empirical study is needed to examine the utility of this framework and its limitations in practice. Nevertheless, we hope the consideration of this framework will lead to more nuanced approaches to examining the real complexities of the United States’ psychedelic regulatory policies currently in effect or in development. Future work might compare the impact of different policies with respect to these domains: legality (criminalization, deterrence, stigma); therapeutic intention (safety, therapeutic outcomes, healthcare utilization); and structure (implementation, feasibility, accessibility). These dimensions might be further explored through subdimensions. For example, one aspect of therapeutic intention is the level of therapeutic specificity, or the degree to which psychedelic use is meant to address a precise, diagnosable problem (e.g., seeking remission of an individual’s PTSD diagnosis versus generally increasing self-awareness).

This framework can also guide efforts for future public health campaigns, specifically identifying strategies for mitigating risk and enhancing safety. For clinicians, evaluation of these policies’ health outcomes is highly relevant, particularly as some therapeutic uses will occur outside of conventional healthcare settings. Finally, conducting ongoing evaluations of policies and selecting meaningful outcome measures will be necessary for making any future comparisons and determining which regulatory options are best suited for maximizing safety and societal benefits.

Utilizing a multi-dimensional framework to consider psychedelic policy options beyond the federal CSA is a critical first step in understanding the complex landscape of psychedelic uses in both medicalized and community settings.